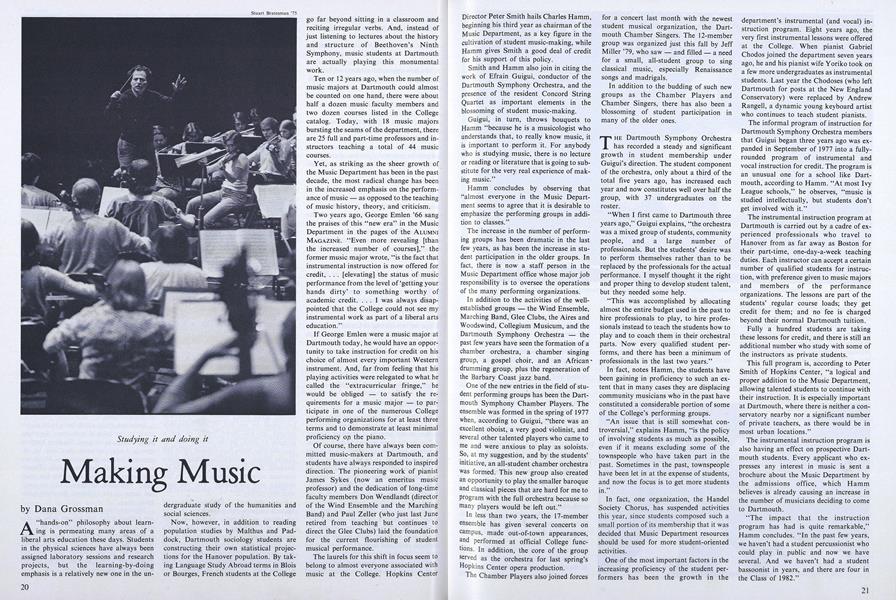

Studying it and doing it

A "hands-on" philosophy about learning is permeating many areas of a liberal arts education these days. Students in the physical sciences have always been assigned laboratory sessions and research projects, but the learning-by-doing emphasis is a relatively new one in the undergraduate study of the humanities and social sciences.

Now, however, in addition to reading population studies by Malthus and Paddock, Dartmouth sociology students are constructing their own statistical projections for the Hanover population. By taking Language Study Abroad terms in Blois or Bourges, French students at the College go far beyond sitting in a classroom and reciting irregular verbs. And, instead of just listening to lectures about the history and structure of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, music students at Dartmouth are actually playing this monumental work.

Ten or 12 years ago, when the number of music majors at Dartmouth could almost be counted on one hand, there were about half a dozen music faculty members and two dozen courses listed in the College catalog. Today, with 18 music majors bursting the seams of the department, there are 25 full and part-time professors and instructors teaching a total of 44 music courses.

Yet, as striking as the sheer growth of the Music Department has been in the past decade, the most radical change has been in the increased emphasis on the performance of music — as opposed to the teaching of music history, theory, and criticism.

Two years ago, George Emlen '66 sang the praises of this "new era" in the Music Department in the pages of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. "Even more revealing [than the increased number of courses]," the former music major wrote, "is the fact that instrumental instruction is now offered for credit, ... [elevating] the status of music performance from the level of'getting your hands dirty' to something worthy of academic credit. ... I was always disappointed that the College could not see my instrumental work as part of a liberal arts education."

If George Emlen were a music major at Dartmouth today, he would have an opportunity to take instruction for credit on his choice of almost every important Western instrument. And, far from feeling that his playing activities were relegated to what he called the "extracurricular fringe," he would be obliged — to satisfy the requirements for a music major — to participate in one of the numerous College performing organizations for at least three terms and to demonstrate at least minimal proficiency op the piano.

Of course, there have always been committed music-makers at Dartmouth, and students have always responded to inspired direction. The pioneering work of pianist James Sykes (now an emeritus music professor) and the dedication of long-time faculty members Don Wendlandt (director of the Wind Ensemble and the Marching Band) and Paul Zeller (who just last June retired from teaching but continues to direct the Glee Clubs) laid the foundation for the current flourishing of student musical performance.

The laurels for this shift in focus seem to belong to almost everyone associated with music at the College. Hopkins Center Director Peter Smith hails Charles Hamm, beginning his third year as chairman of the Music Department, as a key figure in the cultivation of student music-making, while Hamm gives Smith a good deal of credit for his support of this policy.

Smith and Hamm also join in citing the work of Efrain Guigui, conductor of the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra, and the presence of the resident Concord String Quartet as important elements in the blossoming of student music-making.

Guigui, in turn, throws bouquets to Hamm "because he is a musicologist who understands that, to really know music, it is important to perform it. For anybody who is studying music, there is no lecture or reading or literature that is going to substitute for the very real experience of making music."

Hamm concludes by observing that "almost everyone in the Music Department seems to agree that it is desirable to emphasize the performing groups in addition to classes."

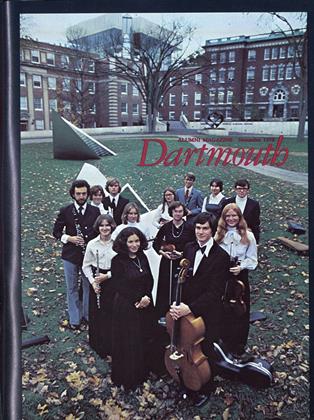

The increase in the number of performing groups has been dramatic in the last few years, as has been the increase in student participation in the older groups. In fact, there is now a staff person in the Music Department office whose major job responsibility is to oversee the operations of the many performing organizations.

In addition to the activities of the wellestablished groups - the Wind Ensemble, Marching Band, Glee Clubs, the Aires and Woodswind, Collegium Musicum, and the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra - the past few years have seen the formation of a chamber orchestra, a chamber singing group, a gospel choir, and an African drumming group, plus the regeneration of the Barbary Coast jazz band.

One of the new entries in the field of student performing groups has been the Dartmouth Symphony Chamber Players. The ensemble was formed in the spring of 1977 when, according to Guigui, "there was an excellent oboist, a very good violinist, and several other talented players who came to me and were anxious to play as soloists. So, at my suggestion, and by the students' initiative, an all-student chamber orchestra was formed. This new group also created an opportunity to play the smaller baroque and classical pieces that are hard for me to program with the full orchestra because so many players would be left out."

In less than two years, the 17-member ensemble has given several concerts on campus, made out-of-town appearances, and performed at official College functions. In addition, the core of the group served as the orchestra for last spring's Hopkins Center opera production.

The Chamber Players also joined forces for a concert last month with the newest student musical organization, the Dartmouth Chamber Singers. The 12-member group was organized just this fall by Jeff Miller '79, who saw - and filled - a need for a small, all-student group to sing classical music, especially Renaissance songs and madrigals.

In addition to the budding of such new groups as the Chamber Players and Chamber Singers, there has also been a blossoming of student participation in many of the older ones.

THE Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra has recorded a steady and significant growth in student membership under Guigui's direction. The student component of the orchestra, only about a third of the total five years ago, has increased each year and now constitutes well over half the group, with 37 undergraduates on the roster.

"When I first came to Dartmouth three years ago," Guigui explains, "the orchestra was a mixed group of students, community people, and a large number of professionals. But the students' desire was to perform themselves rather than to be replaced by the professionals for the actual performance. I myself thought it the right and proper thing to develop student talent, but they needed some help.

"This was accomplished by allocating almost the entire budget used in the past to hire professionals to play, to hire professionals instead to teach the students how to play and to coach them in their orchestral parts. Now every qualified student performs, and there has been a minimum of professionals in the last two years."

In fact, notes Hamm, the students have been gaining in proficiency to such an extent that in many cases they are displacing community musicians who in the past have constituted a considerable portion of some of the College's performing groups.

"An issue that is still somewhat controversial," explains Hamm, "is the policy of involving students as much as possible, even if it means excluding some of the townspeople who have taken part in the past. Sometimes in the past, townspeople have been let in at the expense of students, and now the focus is to get more students in."

In fact, one organization, the Handel Society Chorus, has suspended activities this year, since students composed such a small portion of its membership that it was decided that Music Department resources should be used for more student-oriented activities.

One of the most important factors in the increasing proficiency of the student performers has been the growth in the department's instrumental (and vocal) instruction program. Eight years ago, the very first instrumental lessons were offered at the College. When pianist Gabriel Chodos joined the department seven years ago, he and his pianist wife Yoriko took on a few more undergraduates as instrumental students. Last year the Chodoses (who left Dartmouth for posts at the New England Conservatory) were replaced by Andrew Rangell, a dynamic young keyboard artist who continues to teach student pianists.

The informal program of instruction for Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra members that Guigui began three years ago was expanded in September of 1977 into a fullyrounded program of instrumental and vocal instruction for credit. The program is an unusual one for a school like Dartmouth, according to Hamm. "At most Ivy League schools," he observes, "music is studied intellectually, but students don't get involved with it."

The instrumental instruction program at Dartmouth is carried out by a cadre of experienced professionals who travel to Hanover from as far away as Boston for their part-time, one-day-a-week teaching duties. Each instructor can accept a certain number of qualified students for instruction, with preference given to music majors and members of the performance organizations. The lessons are part of the students' regular course loads; they get credit for them; and no fee is charged beyond their normal Dartmouth tuition.

Fully a hundred students are taking these lessons for credit, and there is still an additional number who study with some of the instructors as private students.

This full program is, according to Peter Smith of Hopkins Center, "a logical and proper addition to the Music Department, allowing talented students to continue with their instruction. It is especially important at Dartmouth, where there is neither a conservatory nearby nor a significant number of private teachers, as there would be in most urban locations."

The instrumental instruction program is also having an effect on prospective Dartmouth students. Every applicant who expresses any interest in music is sent a brochure about the Music Department by the admissions office, which Hamm believes is already causing an increase in the number of musicians deciding to come to Dartmouth.

"The impact that the instruction program has had is quite remarkable," Hamm concludes. "In the past few years, we haven't had a student percussionist who could play in public and now we have several. And we haven't had a student bassoonist in years, and there are four in the Class of 1982."

From the attendance at concerts, and all other observations, it does not appear that the quality of the orchestra's performances has suffered from the increase in student participation and the decrease in professional ringers. In the three years that Guigui has been at the helm of the orchestra, the group has attempted more and more ambitious programs - and carried them off successfully, as attested to by the critical accolades from the College and regional media.

One reviewer wrote in The Dartmouth of a concert last year: "No one deserves more credit for the success of Saturday's Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra concert than conductor Efrain Guigui. ... Those who have attended any of the orchestra's rehearsals must respect the conductor's dedication, enthusiasm, and, above all, patience."

"Equally admirable in Guigui's rehearsal technique," the review continued, "are his intimate knowledge of the pieces being performed and his ability to mold the orchestral sound in accordance with that knowledge. This often involves frequent repetitions of the same phrase and patient explanations of his intentions, but the final outcome of such hard work was ... a spirited and strong performance."

"Guigui has shown that he can bring out the best in student musicians," Smith notes of the conductor's talents, "and that is a tremendously important gift."

Interestingly enough, all of Guigui's career until he came to work with the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra involved play- ing with and conducting professionals (and he is still conductor of the State of Vermont's professional orchestra). As a clarinetist, he performed under the batons of some of the greatest names in conducting - Otto Klemperer, Herbert von Karajan, and Clemens Krauss - and as a conductor himself he has led the orchestras of the Casals Festival, American Ballet Theater, and Bennington Composers' Conference: distinguished company, indeed.

He says of his work with the students at Dartmouth: "They're beautiful; they want to make music, and with the right advice, you know that they can talk the same language. With students, you need to help them more, and you need to be more patient. But since you get many more rehearsals than are usually allowed with a professional orchestra, in actual performance you find that often more of your musical ideas are coming across."

Of the orchestra's impressive performance last spring of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, Guigui explains: "The group was very interested in doing something of this caliber. And interested students, in spite of their inexperience, can find a way to stretch artistically to reach a goal they didn't know they could attain until they tried."

STUDENT performers at Dartmouth get a chance to make music in all kinds of combinations — from the full orchestra all the way down to solo recitals. One of the groups at about the half-way mark in size is the Collegium Musicum, a small instrumental and vocal ensemble whose focus was recently revamped. Originally a forum for the performance of early and Renaissance music, the group has just added to its repertoire the contemporary literature formerly performed by the now-defunct New Music Ensemble. The Collegium will serve as a medium for both formal and informal performances of works from every part of the western musical spectrum.

Solo musicians and small chamber combinations are offered a performance opportunity through two series of concerts sponsored by the Music Department. The Wednesday Noon and Sunday at 4:00 Concerts are presented most weeks during term-time. Instituted seven years ago, the. free events have become very popular in recent years - both in terms of the number of students interested in performing and in the growth of audience attendance.

Another important part of the program Dartmouth has for cultivating student interest in music-making is giving them an opportunity to play with professionals in key positions. "I inherited a policy which makes a lot of sense," says Guigui, "that the symphony orchestra should serve as a platform to expose the performing faculty as soloists and should also give students the experience of playing with professional soloists." Three members of the resident Concord String Quartet have appeared as soloists with the orchestra, in addition to being teaching members of the faculty and performing as a quartet and in other chamber combinations at Hopkins Center.

And last spring, the orchestra had the unprecedented opportunity of playing with the Beaux Arts Trio — probably the foremost ensemble of its type in the world. The Trio was at Hopkins Center to give a concert by themselves and one with the Concords; while they were in Hanover, they also joined with the orchestra in a performance of Beethoven's Triple Concerto - rarely heard because it requires three top-flight soloists.

"To mix a few professionals with the students is a very good thing," acknowledges Guigui, "for they are helped and supported by them and they learn from them.

"In the orchestra we have permanent professionals in the first chair violin and cello. And far from being shown up unfavorably by comparison with them, the students gain a good deal by their presence. The students are able to learn technique from them - advice on fingerings and bowings - and how to carry out musical interpretations. We need at least these two - they make all the difference."

Another role professionals play in encouraging student music-making at Dartmouth is in conducting master classes. From time to time, some of the internationally renowned "imported" artists who come to Hopkins Center are able to stay in Hanover long enough to work on an intensive basis with a few undergraduates who have reached a fairly high level of proficiency in their instruments. Cellist Janos Starker and French horn virtuoso Barry Tuckwell are two performers who in recent years have augmented the College's own program of instrumental instruction in this way.

Peter Smith also cites the stimulus of having composers on the music faculty as another important facet in encouraging music-making. He calls this a "sign of the health and well-being of the department. Really, having composers is 'square one,' since the study of any art must begin with its creator and we have two composers of international standing [Jon Appleton and Christian Wolff]."

A wholly new venture which is also connected with the focus on student music is just now in the formative stages. The Music Department is about to create a new performing organization called Vox Nova, which will be directed by Guigui. To be formed from the teaching faculty, the group is envisioned as a professional, touring, recording ensemble that Smith hopes "will do credit to the name of Vox Nova." The group may occasionally be augmented by other professionals or by some of the very best student musicians, and it will draw its programs from the literature of past eras as well as from the realm of important contemporary composition.

THE fact that such a quality ensemble can be formed from the faculty is a definite sign of the change in emphasis to music-making in the department. Smith wrote several years ago in a Concord String Quartet program about the thoughts that had lain behind the College's residency invitation to the Concords. He said, having decided on a string quartet as the most likely kind of group for a residency, "the next question was a classically simple one: build one or bring one?" He went on to admit, "It isn't being unkind or modest to say that at that time we did not have anyone here with the time, temperament, or contacts to go in for quartet-building."

Yet just four years after the Concords joined the Dartmouth Music Department, there are sufficient resources to go in for quality "building."

While there may be some financial burdens imposed by having a group the caliber of the Concords at Dartmouth, and by hiring the kind of instrumental instructors who can make Vox Nova a reality, Smith notes that it has been possible to shift the emphasis of the Music Department "without straining the budget allocated for music at the College."

Hamm has praise for the College deanery for seeing the importance of the instrumental instruction program and making it financially possible, and Smith has words of appreciation for the Friends of Hopkins Center, who have assisted in the Beaux Arts Trio and Concord residencies and contributed to the orchestra coaching budget the first year Guigui conducted the group.

But, lending a historical perspective to the current blossoming of music-making, Smith also points out that "at the time of the suspension of the Congregation of the Arts [one of the country's top summer arts festivals from 1963 until its termination in 1970], the College administration made it clear that a compensation for that would be a concentration on developing more indigenous resources."

"THE new policy appears to be good not only for the music department but for the whole musical climate at Dartmouth as well," George Emlen concluded in his commentary. "A lot of music is being seriously studied and performed, but without the pall of conservatory elitism."

The impact on the students themselves of the policy encouraging student music-making is perhaps best captured by Guigui: "It would probably be the goal of every student musician someday to play with soloists of the caliber of the Beaux Arts Trio, and we have done that, and to play Beethoven's Ninth, and we have done that."

Teacher-conductor Efrain Guigui in action (agitato) and repose (lent et grave)

Dana Grossman writes on the arts of theUpper Valley for various media.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

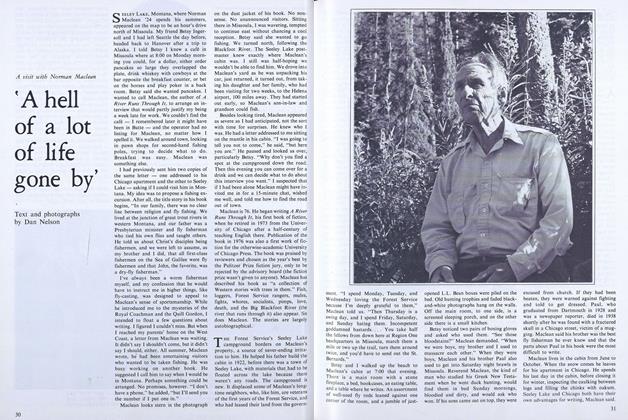

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleThe Joy of Moving

November 1978 By W.B.C. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWhy the NCAA

November 1978 By SEAVER PETERS '54

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFour Alumni Awards

JULY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureJUNE IN HANOVER

JUNE 1990 -

Feature

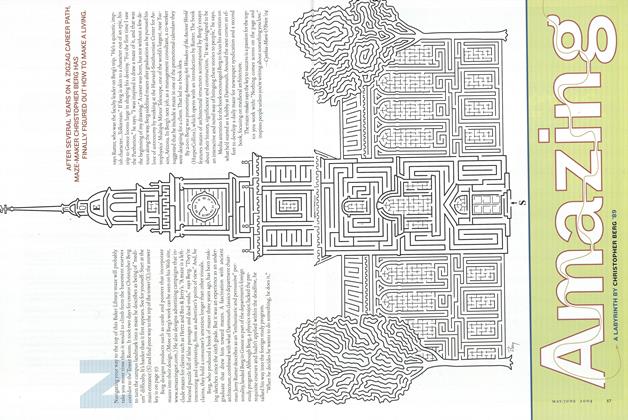

FeatureAmazing

May/June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/Aug 2013 By Mark Brosseau ’98, Mark Brosseau ’98 -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40