Body Of Knowledge

An anatomy course provides unexpected lessons in humanity.

Nov/Dec 2003 Kirsten Andrews ’97An anatomy course provides unexpected lessons in humanity.

Nov/Dec 2003 Kirsten Andrews ’97An anatomy course provides unexpected lessons in humanity.

When I was a junior in high school I took a course in human physiology, which included the dissection of a cat. Several of my classmates expressed concern about dissecting a cat, since many of us had cats as pets and were uncertain about cutting them up. But not me. I was sure that I understood the utility of the exercise and was prepared to put aside my feelings in pursuit of knowledge. In retrospect it is not surprising that, on day one, I was the only member of the class to faint and have to spend the day sitting in the hallway drinking Gatorade. I came in at lunchtime for the next few days to catch up on the dissection and I thought, "This seals the deal—I'm definitely not going to medical school."

That was the only career idea I had when I arrived at Dartmouth College in the fall of 1993: anything but medicine. I chose my courses to include as few of the subjects I had studied in high school as possible because I was amazed at the existence of so many subjects I had never heard of, and I didn't want to waste any time on the familiar. My freshman fall I had my first exposure to environmental science, novels by Toni Morrison and anthropological theories about the domestication of plants and animals. I had never been to an opera, so I took a seminar on German opera during my first winter in Hanover. I had played the cello for almost 10 years when I got to college, and at the end of my first year I gave it up and began tuba lessons. I had some dramatic failures, including a sculpture course whose evidence was swiftly deposited in the dumpster behind Ben & Jerry's. I also acquired new passions, including the Spanish language, which I had never spoken before, and the tuba, both skills I continue to use fondly and frequently.

I graduated from Dartmouth, having majored in anthropology, eager to continue trying new things until I found the perfect career. After two years of working at several different jobs, including teaching, bartending and nonprofit fundraising, I decided I wanted to try medicine. I looked back at my four years at Dartmouth and knew I was well versed in that particular blend of fearlessness and humility that it takes to leave what you know how to do and learn something new.

Even so, it was with quite a bit of apprehension that I entered the anatomy lab on the first day at Dartmouth Medical School. I was so afraid that I would lose control of my own body that I didn't worry very much about the cadaver we were to be dissecting, until I saw it. I was hoping for a little more time—some physiology classes, a speech about the importance of the moment from a professor or a fellow student—just to get used to the idea. The desire for a little more staving off was tangible among my classmates in the lab. We put on non-latex gloves (in case of some allergy we hadn't yet discovered) and took them off again to switch sizes. We put on scalpel blades, took them off again, tested the forceps and the hemostats. My lab group and I discussed for a full five minutes where the center of the back was, just to put off making that first cut. I was terrified.

Up until that point, there really was nothing that distinguished this person face-down on a table from someone who was just asleep. You're not supposed to cut people; its just not done. I can't remember who made the first cut after all, though it wasn't me. But nothing happened. No one screamed or jumped, the body didn't bleed, and we were on to Step 2 in Grant'sDissector: "Reflect the skin in the area bounded by points X, M and R." Once there was a task to be done—the physically demanding and completely foreign task of removing the skin—I could concentrate on following directions, making my cuts close to the surface so I didn't damage anything, working with my fingers to finish a job. There were a lot of things that surprised me about the first day in anatomy lab: I was surprised at how easily the skin yielded to the scalpel, and how strong it was when I used my fingers to pull it back. I was surprised at the color of the fat, inappropriately bright, highlighter yellow; by the muscles' lack of color, a dull brownish-pink that suggested vibrant red washed out by preservative; and by how heavy the body felt when we tried to lift or move it, much heavier than a person. I was surprised at my own curiosity, and how easy it was to lose myself in the situation, as if these body parts had been laid before me without ever having belonged to anyone before then. I was surprised to find that at the end of the lab session I was starving.

Throughout the 20-week anatomy course I was alternately engrossed and horrified. The cadavers taught me to identify structures and how they are connected, and at the same time thrilled me with the intricacy and grace of our species. Humans are so beautifully and carefully put together—sometimes fragile and sometimes incredibly strong. I learned to be comfortable within a body's space, digging inside for some elusive nerve, moving it around, sometimes forcing it into positions that demonstrated its lifelessness unquestionably. Being able to name the parts and know their functions made it easier to later invade the space of living patients by performing cardiac exams, testing joints, pushing on tender bellies. Still, learning the manual skills of dissection was difficult for me, and I ruined more than one demonstration of an artery or an intricate web of nerves in the process.

We changed cadavers four times throughout the course, and I was struck by how each cadaver seemed no more than a collection of parts. I looked for clues about each persons history. Did she have yellow fingers or teeth from smoking? Was he right-handed? Did they have tattoos? How did her job make its mark on her body? But although these signs did exist, I could never deduce what I wanted to learn from them—how the events that marked their bodies had affected the emotional lives and relationships of the bodies' owners. Some people had tattoos, but these symbols didn't explain what had been so important that people wrote them on their bodies. Some bodies had scars, but they didn't explain how the patients had felt about the surgeries they had undergone or the wounds they had endured. One cadaver we worked on had four hernias, and I wanted to know whether he had thought of his weakened abdominal walls as traitors the way I think of my injured body parts, and whether they had affected his ability to exercise or pick up his grandchildren.

I often felt our poking around inside their bodies was pornographic, as if these whole people had been reduced by our dissection to nothing more than their physical parts. I wanted them to have the chance to explain themselves, and I wanted to be able to explain myself, too. I would like to believe that in this life we can explain our actions, and that people will allow our explanations to temper the harshness of what we have done or left undone. But in the anatomy lab, between the cadavers and me, there were no explanations, only the bare evidence of what we all had done.

I decided not to donate my body to a medical school because I was afraid to be judged, even after my death, by the evidence of my body alone, without the tem- pering testimony of my humor or hard work. What would students think when they saw a nipple ring on an old woman? I was certain that no one who had ever dissected a cadaver could possibly donate her or his body to an anatomy course.

The conclusion of our course took place well after the final exam. After Howard, our lab technician, cremated the bodies, we held a memorial service for the families of the people who had been our first patients. It was there that we heard the stories I had wanted to know in the lab. To my relief, many of the people who had given their bodies were doctors, who knew exactly how imperfect we were as dissectors. All of my questions weren't answered, but the humanity of the anatomy lab's collection of parts had been restored.

Maybe knowing in advance about the people who had given this invaluable gift would have reminded me of their humanity and wholeness throughout the course. Maybe it would have made me unable to dissect at all by forcing me to think of people instead of their parts. But I know that when I speak to patients about their pains or when I do surgery, I want to think of them as whole people. I want to consider their pains and the results of their surgeries as issues that impact full, vibrant lives. In anatomy I learned how to detach myself from the people who owned the bodies and to concentrate on their parts. My next task, which will continue throughout my life, will be to learn how a persons body parts affect how he or she experiences life, and to strive to remember always the wonder and grace of the human person, healthy and whole.

Klrsten Andrews is a third-year DMSstudent. This essay is based on a piece that appeared in Dartmouth Medicine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

November | December 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE -

Feature

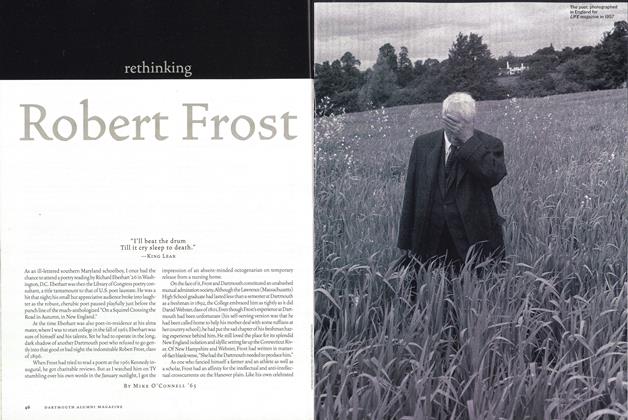

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

November | December 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

FeatureSimply Seth

November | December 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

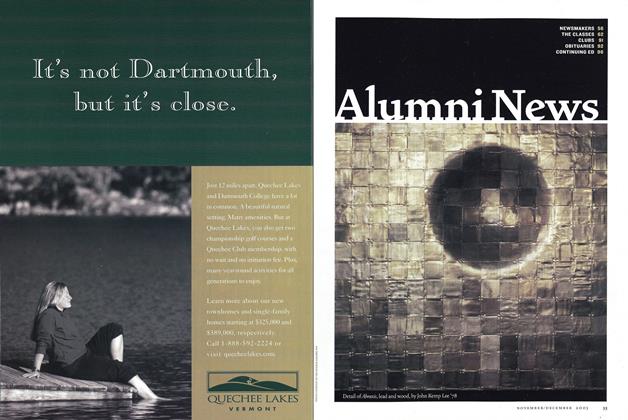

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEFrugal Brugals

November | December 2003 By Nelson Bryant ’46

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClose to Home

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 By APOORVA DIXIT '17 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Devil and Dan Club

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jim Collings ’84 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMutual Transformation

Mar/Apr 2007 By Joanne A. Herman ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPumped Up

Jan/Feb 2007 By Joel Lasky ’54 with Dan Anzel ’55 and Don Kennedy ’54 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe “Happy” Swindler

May/June 2011 By John Grossman ’73 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBlood, Guts, and Beer

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By WILLIAM LAMB ’67