The Overtreated American

More health care means healthier lives for all of us, right? Not according to a team of Dartmouth researchers led by Dr. John Wennberg.

Nov/Dec 2003 SHANNON BROWNLEEMore health care means healthier lives for all of us, right? Not according to a team of Dartmouth researchers led by Dr. John Wennberg.

Nov/Dec 2003 SHANNON BROWNLEEMORE HEALTH CARE MEANS HEALTHIER LIVES FOR ALL OF US, RIGHT?NOT ACCORDING TO A TEAM OF DARTMOUTH RESEARCHERS LED BY DR. JOHN WENNBERG.THEY'RE PROVING THAT THE EXCESS CARE MANY AMERICANS RECEIVE NOT ONLY PERPETUATESTHE STATUS QUO OF THE UNINSURED-IT MAY BE SHORTENING LIVES.

DR. JOHN WENNBERG DID NOT BEGIN HIS CAREER IN PUBLIC HEALTH INTENDING TO STIR UP TROUBLE, BUT HE COULDN'T IGNORE DATA.

It was the 19705,and Wennberg was a young doctor at Harvard, working on a federally funded grant aimed at helping the state of Vermont create a regional health care program. "It was a Great Society project," Wennberg recalls, and his first step, with Harvard colleague Dr. Alan Gittelsohn, was to define what kind of health care Vermonters might need in different parts of the state. They looked at statistics kept by the state for the rate of surgeries and hospitalizations in 13 different regions, expecting, he says, "to see big pockets that were being underserved." But when they began comparing the actual amounts of medical care citizens in the various regions were using, they were in for a surprise.

"The data was chaos," says Wennberg. "It made absolutely no sense." They found enormous variation in the medical care that was being delivered in different parts of Vermont. In one place, for example, the rate of dilation and curettage, a gynecological procedure, was 30 per 10,000 persons; in another, it was 141. Nursing home admissions swung from a low of 13 per 10,000 in one region to 100 in another. Within a single region, rates of one procedure would be high and another low. The two doctors knew that the medical needs ofVermonters could not possibly explain what they were seeing; nor could their observations be due to variations in income. Vermont is an unusually homogeneous state, where the vast majority of citizens are white and middle class. The only pattern the researchers could discern was that more surgeries were performed in areas with more surgeons, there were more nursing home admissions in regions with more nursing home beds, and more hospitalizations in regions with more hospital beds.

Wennberg and Gittelson were forced to come to a startling conclusion: The supply of doctors and hospital beds—rather than how sick people were—was governing the rate of hospitalizations and procedures in different regions. What's more, they had their first inklings that Vermonters living in regions with the highest rates of medical procedures and hospitalizations were not any healthier than those who were getting considerably less care.

This was an idea that was not exactly welcomed by the medical establishment. After being turned down by all the medical journals, Wennbergs team finally found a home for their results in the journal Science, where their paper was written off by their colleagues in medicine.But ignoring Wennberg has not made his ideas go away. After three decades at Dartmouth Medical School, where he has been director of the Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences since its founding in 1989, his voice is finally being heard by health care policymakers. Since those early days in Vermont, Wennberg and his group of researchers have amassed the evidence to make a simple but powerful argument: More medical care does not necessarily mean better health.

The argument may be simple, but it is also profoundly important to the national debate over health care reform, which has foundered on two seemingly intractable problems. The first is access to care. With a health care economy of more than $1.4 trillion, the United States spends two to four times per capita what other developed nations spend, yet more than 43 million of us don't have health insurance. The second problem we face is spiraling health care costs. After a brief respite in the 19905, when HMOs squeezed profits from doctors and hospitals, medical costs are soaring again at a rate of 10 to 12 percent a year. Neither lawmakers nor citizens can see a way out of this dilemma, because reining in costs while simultaneously increasing access to care invariably raises the specter of medical rationing.

Implicit within our worries about rationing is the assumption that more health care means better health, and that the only people who are at risk of falling seriously ill or dying prematurely are those who don't have sufficient access to medical treatment. But as Wennberg's group is showing, more medicine can sometimes be bad not just for our pocketbooks, but also for our well-being. "There is an optimum level of care that helps you live as long and as well as possible," says Wennberg. "Then there's excess care, which not only doesn't help you live longer, but may shorten your life or make it worse. Most Americans are getting excess care." Between 20 and 30 percent of health care dollars, according to his groups most recent estimates, are spent on procedures, office visits, drugs, hospitalization and treatments that do absolutely nothing to improve either the quality or length of our lives (see "A Patient Approach," next page). At the same time, treatment that offers clear benefits of ten fails to reach many Americans, even those who are insured.

That idea opens the possibility of thinking about health care reform in an entirely new light. Lawmakers, insurers and the health care industry might be able to save money by concentrating on improving the quality of care, rather than controlling costs. "Health care reform in the United States has to be driven by improving quality of care," says Jonathan Skinner, a Dartmouth economics professor and a senior research associate with the Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences. Better health care will mean more medicine for some, particularly the uninsured, but for many of us it will mean less.

Support for this idea can be found in Strasenburgh Hall, the dilapidated converted dormitory on the Dartmouth Medical School campus that houses Wennberg's team of economists, doctors and epidemiologists. Each year the group publishes scores of papers, as well as the Dartmouth Atlas ofHealth Care, a compendium of medical statistics and patterns of health care spending in 306 regions of the country (to view it, go to www.dartmouthatlas.org). The Atlas, which is supported by a $1 million grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, draws on data from Medicare and large insurers such as Blue Cross to assess rates of medical utilization—numbers of pro- cedures, specialists, days in the hospital and Medicare spending per capita—in different regions of the country.

At 66, Wennberg himself is a handsome, heavy-jawed man of medium build, with graying hair curling over his ears and tanned, muscular hands that make him look more like a gentleman rancher than a maverick academic. But his ideas no longer seem as wild as they once did. Wennbergs work is now being bolstered by independent researchers and the Institute of Medicine, a nonprofit organization that dispenses science-based advice on matters of biomedical science and health, and other independent researchers, as well as by a continuous stream of research from his Dartmouth team, which is showing precisely how the nation misspends its health care dollars.

Take, for instance, the regions surrounding Miami and Minneapolis, which represent the high and low ends of Medicare spending. Lifetime Medicare expenses for a typical 65-year-old in Miami is $50,000 more than for a 65-year-old in Minneapolis. During the last six months of life, a period that typically accounts for more than 20 percent of a Medicare patients total costs, a Miamian spends twice as many days on average in the hospital than his counterpart in Minneapolis, and is twice as likely to see the inside of an intensive care unit.

All the regional variation would make perfect sense if higher consumption of medical services occurred in regions where citizens are the sickest. But as Wennberg and Dartmouth colleagues Dr. Elliott Fisher and economist Skinner point out in a paper, "Geography and the Debate over Medicare Reform," which appeared online in a recent issue of the journal Health Affairs, underlying level of illness does not account for the differences in spending among regions. If it did, the region around Provo, Utah, one of the health iest of the country, would use 14 percent fewer health care dollars than the national average, because its citizens are less likely to smoke, be obese or suffer from strokes, heart attacks and other ailments. Instead, it receives 7 percent more health care dollars than the national average. Elderly people in the region around Richmond, Virginia, by contrast, tend to be sicker than most Americans and should receive 11 percent more than the national average, rather than the 21 percent less that they actually receive. Nor are those regional differences explained by variations in the cost of care. Provo doctors are not charging significantly more for office visits or lumpectomies than doctors in Richmond, and their patients aren't getting more expensive artificial hips.

Rather, the regional variation is driven in large measure by hospital resources and the number of doctors. In other words, it's supply rather than demand that determines the amount of care delivered. People get more diagnostic tests in regions where there are more MRI machines, and they see more specialists where more specialists set up practice. During the last six months of life, a Medicare beneficiary in Miami sees on average 25 specialists in a year versus two in Mason City, lowa, largely because Miami is home to a lot more specialists.

It would be one thing if all this lavish medical attention were helping people in high-cost regions live longer or better, but that doesn't appear to be the case. Probably the most surprising finding of the Dartmouth group, and the one with the most far-reaching implications for how we think about reforming health care, is that all that extra medicine isn't buying citizens in high-cost regions better health. At the beginning of life, for instance, having more neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and more neonatologists (doctors who specialize in the care of low-birth-weight babies) does not improve infant mortality rates. Dartmouth pediatrician and associate professor David Goodman and colleagues recently published research showing that too few neonatologists—below about 2.7 per 10,000 births—increased the chances that a low-birthweight baby would die by about 8 percent. But having more than about 4.3 neonatologists perio,ooo birthsdidnot improve a lowbirth-weight baby's odds, and some parts of the country have as many as 11.6 specialists per 10,000 births. Similarly, too few NICU beds put infants at heightened risk of dying, but extra beds simply meant that more relatively healthy babies are put into the NICU, with no improvement in the overall mortality rate.

At the other end of life, an overabundance of medical resources and doctors is not helping Medicare recipients live longer or healthier lives. Two papers published earlier this year by Fisher, who is codirector of the outcomes group at the Veterans Administration hospital in White River Junction, Vermont, and several colleagues at Dartmouth and the VA hospital, showed that Medicare recipients in high-cost regions suffer as many disabilities as citizens in low-cost regions, and they don't live any longer. In fact, says Fisher, mortality in high-cost regions appears to be about 2 to 6 percent higher than in the lowest-cost regions of the country.

In other words, more medicine is bad for you.

The most likely explanation for this is that elderly people who live in high-cost regions spend more time in hospitals than citizens in low-cost regions, says Wennberg, "and we know that hospitals are risky places." Patients are exposed to the possibility of medical errors, dangerous drug interactions, life-threatening infections and diagnostic tests that lead to unnecessary and risky treatment. "We've got the most sophisticated and advanced medicine in the world," says Henry Aaron, a health care economist at the Brookings Institute. "But at the high end we've just got more of it, not better medicine."

AN OBVIOUS FIRST PLACE TO LOOK FOR WAYS TO cut excess medical care is in the way hospitals and doctors are paid. "Medicine is the only industry where high quality is reimbursed no better than low quality," says David Cutler, a health economist at Harvard. "The reason we do all the wasteful stuff is we pay for what's done, not what's accomplished."

While that's clearly the case, figuring out the right incentives for health care providers is by no means obvious. Let's say Medicare decided to allocate funds according to how sick people are in a particular region of the country. That would mean some areas, such as Provo and Miami, would see their Medicare budgets capped at a level below current spending. Some Provo and Miami doctors would undoubtedly be encouraged to practice more conservatively, but many others might maintain their incomes either by dropping Medicare patients altogether or giving them even more hysterectomies and CT scans they don't need, thus compensating for lower fees by performing more procedures.

The problem of how to encourage doctors to do less is further complicated by the Wennberg groups finding that the excess medical spending in high-cost regions is not going toward big-ticket procedures, as many people, including health care economists and policymakers, assume. Rather, the bulk of excess care in high-cost regions comes from discretionary treatment: office visits, minor procedures, diagnostic tests. It's doctors admitting patients to the hospital when doing so will do little or nothing to improve their well-being—or lengthen their lives. "When someone with multiple ailments develops pneumonia in the nursing home, you have a choice of admitting him [to the hospital] or making him comfortable," says Fisher. "Doctors and families don't think about the fact that [admitting the patient] almost certainly won't delay death by more than a day or two, or that this is one of the most expensive decisions they can make."

Even when policymakers come up with the right financial incentives for doctors and hospitals, restructuring compensation will constitute only one small component of the reform that's needed to turn medicine into an efficient, effective industry. Think of it this way: At 13 to 14 percent of GDP, health care comprises the nations largest industry, and probably its most complex. Transforming this sprawling behemoth is going to involve a lot more upheaval than, say, the shift that took place in the auto industry when companies went from piecework to the assembly line or the shakeup Hollywood and the music industry now face with the advent of Web entertainment.

Probably the hardest task of reforming health care lies in persuading Americans that access to care—something the uninsured don't have—is not the only flaw in the system, and that improving the quality of care for all could also save money. How much money is at stake? Overtreatment wastes as much as 30 percent of Medicare spending. That means that if spending in high-cost regions could somehow be brought in line with low-cost regions, Medicare alone could save on the order of $32.7 billion. That's enough to keep the Medicare system afloat an additional 10 years, provide better access to care for the elderly in rural regions, or fund a generous prescription drug benefit for seniors. Doctors are just as likely (if not more likely) to overtreat patients with private health insurance. That means the system as a whole is wasting about $420 billion a year, more than enough to cover the needs of the more than 43 million uninsured citizens.

The last attempt at reforming the U.S. health care system failed in large measure because of fears of rationing. Americans were led to believe that any attempt to expand coverage to the uninsuredwhile simultaneously holding down costs—would inevitably lead to rationing. Sure, we feel bad about the estimated 18,000 of our fellow citizens who die prematurely because they lack health care coverage, and about the seniors who are forced to choose between buying food and buying medicine. But Americans want nothing to do with a system like England's, for example, which won't pro vide dialysis to the elderly. And most of us who are now covered by either Medicare or private insurance have little stomach for health care reform that contains even the possibility that our access to expensive, life-saving procedures might be restricted.

Wennberg believes the medical profession has an important role to play in improving the quality of care, but says most doctors aren't yet convinced that cutting down on excess treatment is part of the solution. "We can't fix the problem of overtreatment until medical leaders take it on," says Wennberg. He is now trying to assemble more fine-grained data showing the rates of medical utilization for individual hospitals in a single region or city, in order to provide Medicare, doctors and hospital administrators with clear evidence that the excess care they are providing is not improving patients' health. It has been a long battle for Wennberg, but he's slowly beginning to persuade insurers and doctors that when it comes to medicine, sometimes less is more.

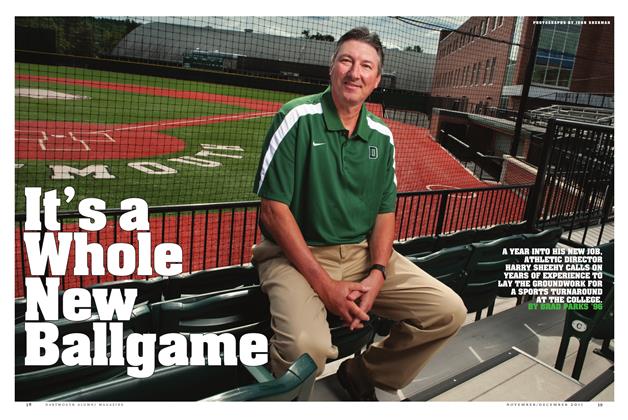

Researchers (from leff) Dr. John Wennberg, econo raist Jonathan Skinner and Dr. Elliott Fisher say more health care does not always mean better healthcare.

It's supply rather than demandamount of care that's being delivered.that determines the

Shannon Brownlee is a senior fellow with the New America Foundation. Her articles about health care policy, cancer research and genetics have appearedin Time, The New York Times, The New Republic and Discover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

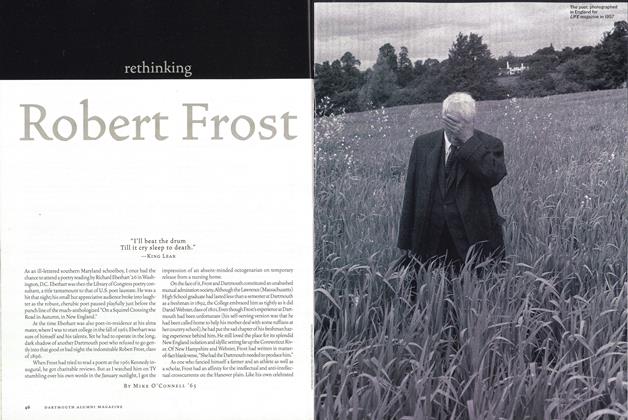

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

November | December 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

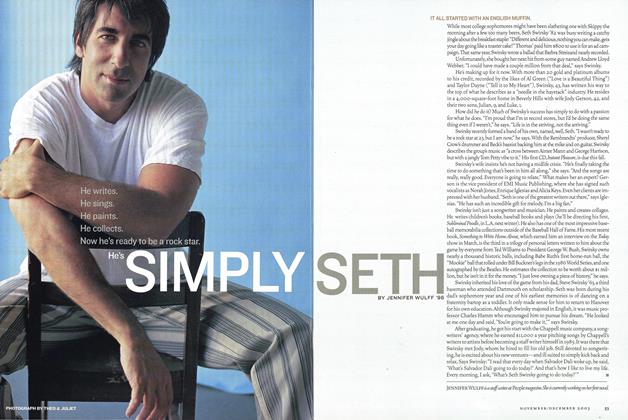

FeatureSimply Seth

November | December 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

Personal History

Personal HistoryBody Of Knowledge

November | December 2003 By Kirsten Andrews ’97 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEFrugal Brugals

November | December 2003 By Nelson Bryant ’46