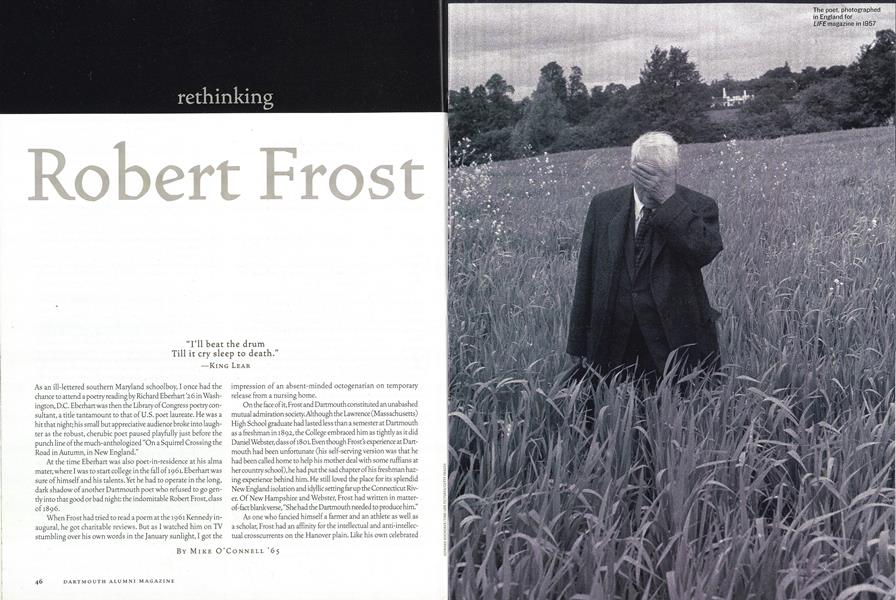

Rethinking Robert Frost

“I’ll beat the drum/Till it cry sleep to death.”

Nov/Dec 2003 Mike O'Connell ’65“I’ll beat the drum/Till it cry sleep to death.”

Nov/Dec 2003 Mike O'Connell ’65“I’ll beat the drum

Till it cry sleep to death.”

—King Lear

As an ill-lettered southern Maryland schoolboy, I once had the chance to attend a poetry reading by Richard Eberhart ’26 in Washington, D.C. Eberhart was then the Library of Congress poetry consultant, a title tantamount to that of U.S. poet laureate. He was a hit that night; his small but appreciative audience broke into laughter as the robust, cherubic poet paused playfully just before the punch line of the much-anthologized “On a Squirrel Crossing the Road in Autumn, in New England.”

At the time Eberhart was also poet-in-residence at his alma mater, where I was to start college in the fall of 1961. Eberhart was sure of himself and his talents. Yet he had to operate in the long, dark shadow of another Dartmouth poet who refused to go gently into that good or bad night: the indomitable Robert Frost, class of 1896.

When Frost had tried to read a poem at the 1961 Kennedy inaugural, he got charitable reviews. But as I watched him on TV stumbling over his own words in the January sunlight, I got the impression of an absent-minded octogenarian on temporary release from a nursing home.

On the face of it, Frost and Dartmouth constituted an unabashed mutual admiration society. Although the Lawrence (Massachusetts) High School graduate had lasted less than a semester at Dartmouth as a freshman in 1892, the College embraced him as tightly as it did Daniel Webster, class of 1801. Even though Frosts experience at Dartmouth had been unfortunate (his self-serving version was that he had been called home to help his mother deal with some ruffians at her country school), he had put the sad chapter of his freshman hazing experience behind him. He still loved the place for its splendid New England isolation and idyllic setting far up the Connecticut River. Of New Hampshire and Webster, Frost had written in matterof-fact blank verse, “She had the Dartmouth needed to produce him.”

As one who fancied himself a farmer and an athlete as well as a scholar, Frost had an affinity for the intellectual and anti-intellectual crosscurrents on the Hanover plain. Like his own celebrated hired man, Frost hated to see a schoolboy made the fool of books, hardly a hazard in Dartmouth’s Animal House heyday. If Harvard University was a place for studying philosophy, Dartmouth College was a place for writing poems (Richard Hovey, class of 1885, had proved that), and for reading them to the kind of town-and-gown audience Frost preferred.

Toward the end of his life one of his annual rites was a special reading for the freshman class at Dartmouth. The readings were held in historic Dartmouth Hall. Although attendance was not mandatory for the school’s 800 freshmen, there was always an overflow crowd.

As a bleary-eyed freshman in the spring of 1962, I was horsing around in the basement ping pong room of a nearly deserted Middle Fayerweather dormitory one gloomy day after lunch. Middle Fayer was situated only 100 feet from Dartmouth Hall, but I had missed the news of Frost s reading that day, or else I had put it out of my mind. Unlike many of my well-prepped classmates from the Northeast, I had not been taught to venerate the New England poet. Middle Fayers Interdormitory Council honcho, Paul Weinberg ’62, stopped down to scold me and another boy for missing the big show.

We moseyed over to Dartmouth Hall and entered a balcony through a side door. Below us sat a rapt delegation of the class of 1965, some of them wearing their freshman beanies. On the stage at the podium stood the hunched, leonine figure of Frost. The first words I heard were, “Now I’m gonna say a poem for you. Some people recite poems; I just say em.” There was an obligatory titter from the dignitaries behind him on the platform; I got the impression Frost had used the line a thousand times before.

For all his antiquity and slowness of speech and movement, Frost was still in casual and complete control. “That one’ll fool ya,” he said with a schoolmaster’s smile after reading “The Road Not Taken.” I thought I knew what he was talking about: The poem was about a lie told by a man who would have you believe he had made a pivotal and perhaps courageous choice early in life “that made all the difference,” when in fact little or no such wisdom or courage had been involved.

The poem said something about Frost as a charlatan, but there was nothing fake about the north-of-Boston accent that helped carry his hill country New England poetry. Vermont was Vuhmont and New Hampshire was New Hampshuh and Dartmouth was Daaahtmuth. His voice was gnarly, dark and deep. There was no effort to dramatize the lines he read; he expected the words and meter to speak for themselves. In certain stretches he would hammer out an insistent, fatalistic iambic pentameter:

And nothing to look backward to with pride

And nothing to look forward to with hope...

His overwhelming weariness seemed appropriate to much of his material:

But I am done with apple picking now

Essence of winter sleep is on the night,

The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.

Although I still thought he put his pants on one leg at a time (and likely needed help with that), I had to admit that he was riding one slick pony. The Dartmouth Hall event was part of the inspiration for my poem “Frost as Farmer,” which concludes:

For his last forty years

He slept in featherbeds

At fashionable colleges

Where he could go on stage

In rumpled suit

And thatched white hair

Toting his pail of chestnuts.

Back in the classroom, Frost’s poems found their way into the reading assignments in English courses I took with professors such as young Noel Perrin and old John Finch. “There was a time when you had to choose” between Frost and T.S. Eliot, Finch told us. Whether that time had passed was still in question. The brilliant Thomas Vance favored the intellectual challenges and soaring imaginations of poets such as Wallace Stevens and Ezra Pound to the “good fences, good neighbors” bromides of Frost, who was no more likely to appear in Professor Vance’s “Modern Poetry” syllabus than was James Whitcomb Riley.

There were other rumblings of something like an in-house mutiny against Robert Frost Superstar. Finch decried the “stage Yankee” element in both the poetry and the public readings. Frost the nature poet had long since withered into Frost the cracker barrel philosopher, Frost the irascible literary critic and Frost the savvy political commentator. In a place where Frost had been such a compelling and persistent personal presence, it became difficult for even the purest of critics to consider the poetry apart from the man. English department chairman Harold Bond talked “motto voce” about forthcoming biographical revelations that would show Frost to be omething of a monster in his family relationships. The poem “Design” was offered by Finch as evidence of Frost’s frightening agnosticism. Among the stories in circulation around Hanover was one that had Frost giving cold counsel to a son who was contemplating suicide: “Do what you have to do.” In another, Frost had confided to someone that the poet in him had died by the time he was 40, but that he had been crafty enough to hold back a passel of good ones to be released at strategic intervals during the rest of his life. I had come to like Eberhart’s unmasked persona; I learned to be suspicious of a man who wrote:

It’s restful just to think about New Hampshire;

At present I am living in Vermont.

The sage of the Green Mountains had no trouble absenting himself from Vermont, either, especially when the leaves began to fall. He knew when it was time to leave off roughing it and settle for room service. Consider a letter written at the tender age of 51: “I didn’t get south scathless. I’m in bed with a cold here in the Webster Hotel in New York. I hope to...take the Orange Blossom Special for Coconut Grove, Fla. on Friday. My address there will be 3670 Avacado Ave.” What better place to write about the New England outback?

After the afternoon in Dartmouth Hall, I did not keep track of any schedule for Frost's subsequent readings on campus. He proved to be a hard man to elude, however. During the fall of 1962 a carload of Dartmouth sophomores had made arrangements to meet some girls at Mt. Holyoke College, several hours south in Massachusetts. We arrived expecting to go to a Saturday night dance on the campus, but no such luck.

The bad news, we were told by one of the girls, was that the dance had been canceled.The good news, so she said, was that it had been canceled because Frost had decided to read his poetry that night in what would have been the dance hall. He likely knew he had a very short time to live; he craved at least one more tonic of adulation before his final exit.

Remarkably, no one complained about the situation. Attention must be paid. The Mt. Holyoke girls and their dates dutifully gave up an evening of rock ’n’ roll to sit at the feet of the wizard. The hall could not hold the crowd; many, myself included, were shunted downstairs to a basement annex where the old mans familiar singsong was piped in. I had the feeling he had slipped a cog by this time, was becoming his own character from “An Old Man’s Winter Night”:

What kept him from remembering what it was

That brought him to the creaking room was age.

He stood with barrels round him—at a loss.

The program had not started on time, and when it was finally over it was close to the dormitory curfew hour for the Mt. Holyoke girls. My dates during my Dartmouth years were few and far between, and Frost had spoiled this one.

The unscheduled Mt. Holyoke show came close to being Frost's final public appearance. It would have been a good way to go out, talking to an overflow crowd of college kids in New England. He had long since achieved his stated goal in life, which was no more nor less than to stick a handful of poems on a high enough shelf so that no one could get at them. But he still wanted to wave from the top of the steeple one more time. And so he came back to Dartmouth.

On November 27,1962, Frost appeared at Hopkins Center, a new, trendy piece of architecture tucked in tightly on a marginal piece of land between the Hanover Inn and Wilson Hall. Having just opened its doors three weeks earlier, the brick-and-glass structure was at odds with most of the rest of the campus's 19th-century buildings. The goal of the edifice—to foster the fine arts at Dartmouth—was also at odds with a certain Big Green element on campus that thought the place was getting a little too artsy-fartsy for its own good.

No doubt preparing for finals while going through the motions of preseason basketball practice, I did not attend the performance. I did not like Hopkins Center, and I thought I had seen and heard enough of Frost. I did not expect that he would have anything to offer I had not heard before. But almost 40 years later I came upon a written version, supposedly a transcript, of his talk that night. Unlike many of his previous lectures, it is unlikely that this one was doctored after the fact for publication, since Frost went into the hospital shortly after the Hopkins Center lecture and never got out.

The rather amazing performance—it must have run a full two hours—included far more than the litany of greatest hits I would have expected. Beginning with some ingratiating comments on the luxurious Hopkins Center amenities, the old man segued deftly into the luxuriance and extravagance and exaggeration that are part of the stuff of poetry. Much of the charm and wisdom that emanated from Frosts mind was a result of his keen and mischievous associative powers, and his penchant for serve-and-volley point-counterpoint. That night in his readings and examples he ran the gamut from Catullus to Mother Goose, drawing on some esoterica that would have blown by me as an undergraduate.

Physically, he was pretty far gone. He had to ask someone to hand him a big-print version so he could decipher his own words. But what an irresistible talker. According to the transcript, he faltered, recovered, backtracked and interrupted his reading with amusing asides and commentary. “And then watch this,” he interjected in the middle of a poem. He set up several “we versus them” arguments on the nature and function of poetry, with the entire audience safely in the “we” category.

But Frosts inveterate contempt for his readers’ collective intelligence —“They cannot look out far/They cannot look in deep”— along with his uncanny ability to horrify, were not to be suppressed in the final performance of his life. Near the end of the program, after cozying up to the audience with golden oldies such as “Stopping By Woods” and “The Road Not Taken,” Frost took dead aim on any cosmic complacency by reading a little-known shocker called “The Draft Horse.”

Unlike some other selections read that night, the words to the compressed and compelling “The Draft Horse” are not quoted in the transcript, and Frost supplied his Hopkins Center audience with neither introduction nor afterword. I wonder if anyone there had previously encountered the poem. It is not included in the Robert Graves and Louis Untermeyer paperback collections of Frost poetry that I studied in college and later taught from. The department of copyrights and permissions at the Henry Holt Cos. in New York has denied me permission to quote here the entire 20-line poem, which describes the preternatural experience of a couple (one thinks of Robert and Elinor Frost) traveling through a malevolent wilderness in the dead of night in a buggy that is said to be “too frail” for the draft horse pulling it. Just as the buggy is overpowered by the huge horse, the beast itself is no match for the stranger who emerges from the woods to unaccountably stab it to death; in its fall, the horse cracks the shaft of the weapon. In the final quatrain, the narrator concludes with all the stoicism he can muster:

We assumed that the man himself

Or someone he had to obey

Wanted us to get down

And walk the rest of the way.

Perhaps the only comforting thing about the poem is the poet’s atypical admission of his own vulnerability, and his unusual position as a participant in a two-person experience. In terms of his own troubled biography, he might be making a final plea that, all things considered, he was more sinned against than sinning.

As the remarkable performance narrowed to a close, Frost admitted to a lonely dread of the darkness lying ahead of him. Yet he also hinted at (threatened us with?) the prospect of a posthumous curtain call:

And I may return

If dissatisfied

With what I learn

From having died.

“Just missed him,” Eberhart had written admiringly of the darting squirrel that eludes the wheels of his car. But for all Frosts hide-and-seek, for all his escapes into and out of the underbrush, in the end you can’t miss him. He hogs the road, blocks our way, hectors us until we understand him wrong or right. “It hurts like everything,” he once wrote, “not to bring my point out more sharply.” After his own conflicted fashion, he was straining with agitated heart to do this until the end. And as we witness the new century’s continuing stream of director’s-cut editions of his writings, we begin to see, 40 years after his death, what Frost meant about a willful return to earth. His lover’s quarrel with the world endures; his prickly conversation with his reader goes on.

Mike O'Connell is a retired dairy farmer in Baraboo, Wisconsin,where he works as a part-time English teacher for the University of Wisconsin-Baraboo. He has self-published two books of poetry.

Excerpts from “After Apple-Picking,” “An Old Man’s Winter Night,” “Neither Out Far Nor

In Deep,” and “The Draft Horse” from THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST edited by

Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1936,1944,1958,1962 by Robert Frost, copyright

1964,1967 by Lesley Frost Ballantine, copyright 1916,1930,1939,1969 by Henry Holt

and Company, LLC, New York. Reprinted by arrangement with the publishers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

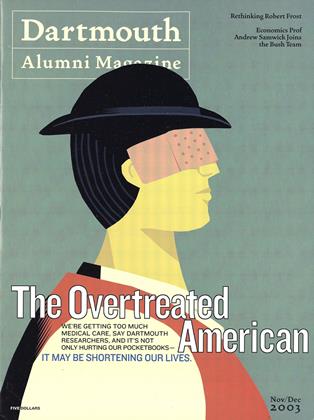

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

November | December 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE -

Feature

FeatureSimply Seth

November | December 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

Personal History

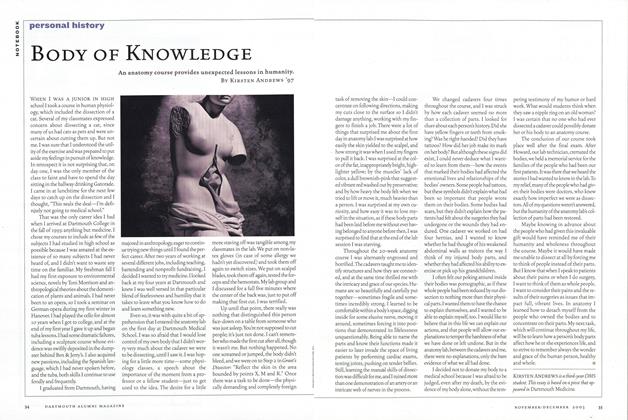

Personal HistoryBody Of Knowledge

November | December 2003 By Kirsten Andrews ’97 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEFrugal Brugals

November | December 2003 By Nelson Bryant ’46

Mike O'Connell ’65

Features

-

Feature

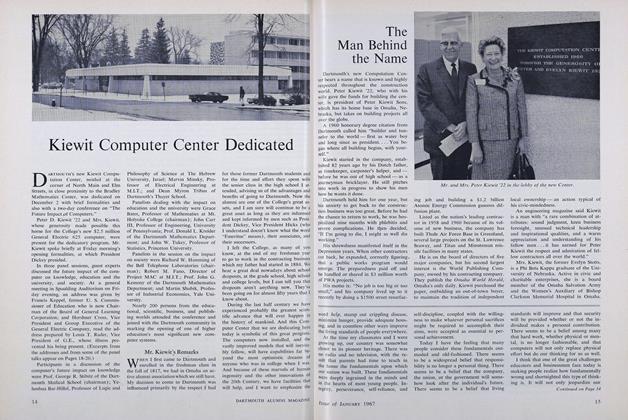

FeatureKiewit Computer Center Dedicated

JANUARY 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

MARCH 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Feature

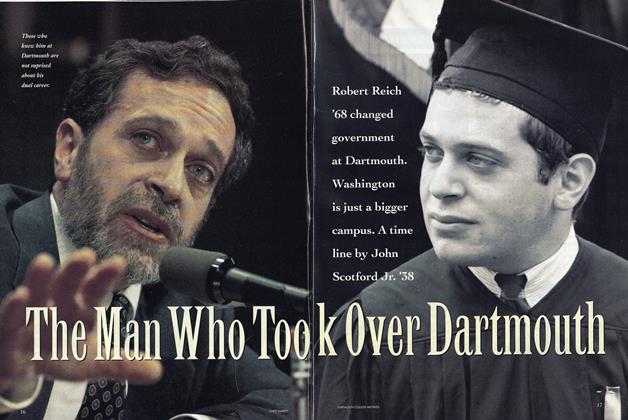

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Cover Story

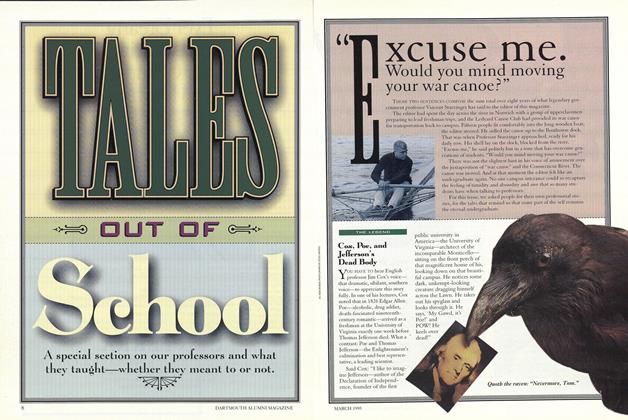

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

MARCH 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Sept/Oct 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74