quote /unquote "It's not too late to salve my psyche, and that of others in my situation. If the College retroactively adjusted some of those C+'s into As, my self-esteem would soar." PETER J. LOGAN '70

ABCs of Grading

THE HIGH GRADES AT DARTMOUTH ("Ais for Abundance," Mar/Apr) call into question the quality of the education experience. After all, the reason grades are so high is that the people paying the bills (students and their families) want high grades. Professors, then, find themselves in a conflict of interest when it comes to grading. If they grade on a curve, many students will be unhappy, which will have economic consequences such as reduced course enrollments in the future.

The people paying the education bill not only want high grades, they also want low standards. Look, for example, at what is called an undergraduate major now. In the old days the majors were academic disciplines; these days majors include a wide range of vocational activities.

High grades express anti-intellectual values. American society would not tolerate the NCAA setting a policy where all teams are virtually guaranteed to win 90 percent of their games. We insist on recognizing athletic excellence. When it comes to intellectual achievement, however, we are reluctant to recognize excel- lence. The students who work hard get the same grade as those who work moderately hard. High grades also mean that postgraduate advancement will be based on other criteria such as standardized tests.

Columbus, Ohio

GRADE INFLATION IS AN AFFRONT to those of us who earned our degrees on the back of hard work and a system designed to reward our efforts. I'm not sure the members of our class were any less intelligent than today's Dartmouth students, but we were a great deal less fragile.

During four decades in medicine, I have had almost daily contact with medical students of virtually every stripe. In the early years it was clear that graduates of the elite Northeastern schools performed at a level modestly above that of their peers. More recently, this has not been the case.

Many of these modern straight A nuggets appear to feel that their native in- telligence is so self-evident there is no rea- son for them to perspire a little in their quest to attain a station in society where they are given the power to commit mayhem on their patients.

Paragons of social conscience, they are far above such mundane matters as accumulating information necessary to arrive at a diagnosis. To get them to do some simple clinical reasoning is a struggle because it is ever so boring. That the patient has a terminal illness is such "a bummer." Perhaps these hothouse flowers could stand a bit of damage. It might toughen them up for the real world. Thank you very much but Id rather spend my time on the graduates of schools of a lesser god. They turn into vastly better physicians.

Absecon, New Jersey RICK GREEN MISSED THE Importance of student evaluations encouraging faculty members to give students high grades. In almost all colleges and universities these evaluations become part of the faculty members dossier and are given considerable weight when the faculty member is up for tenure or promotion.

Not many students will give a good evaluation to the instructor who gave them a C on a midterm examination or research paper, and young faculty are well aware that a student who is doing A or A- work is likely to give them a high mark at the end of the term.

Hamilton, New York

DURING THE YEARS I'VE HAD VARIOUS job interviews, and I do not recall anybody asking about college grades.

Despite my bottom-third class rank, I was accepted by Northwestern's M.B.A. program (now Kellogg). My grades were better there, but not uniformly stellar. Nevertheless the dean offered me the position of director of admissions of Kellogg upon graduation. I chose instead to work in business, first as an investment professional and later as an associate profes- sor at a small business-oriented college. At the final interview for that position, the college president had my spotty Dartmouth transcript in hand yet offered me the teaching position I then held for 11 years.

As an educator, I was encouraged to avoid grade inflation, and my average grades were tracked. I gave occasional D's and E's, which were earned.

I admit my students were not on a par with those currently in Hanover, but I was appalled to see so many Dartmouth educators saying in DAM that they gave higher grades so as not to engender animosity from their students. I told my students that my goal was not to be liked but to be respected, and my student feedback was normally quite high.

There is no easy answer at Dartmouth and similar schools—particularly in light of the high grade-point averages required by topnotch graduate schools. But there is more to life than grades. A GPA alone is a callous and arbitrary figure, fraught with potential disappointment. Grade inflation has compromised what life should be about.

Blue Hill, Maine

THERE IS NO SIMPLE ANSWER TO the grades conundrum. As a senior I was rejected at the graduate school of my choice, despite straight As in my 14- course biology major (itself no mean feat).The rejection letter sniffed that their university accepted only undergraduates with straight As in all subjects. As my classmates can attest, anybody with straight As at Dartmouth in those days was considered to walk on water.

The timeless lesson? Take grades into account, and take into account what institution granted them.

Clandeboye, Canada

WHEN I WAS A STUDENT AT COLUMBIA Law School, they had changed the names of their grades to: E, excellent; VG, very good; G, good; P, pass; U, unsatisfactory—an innovative approach.

With this grading system they could give G as an average grade and not be insulting their high-powered students, who obviously were all doing at least good work on average. They also did not put grade point averages or class rankings on transcripts; though they did have honor rolls and being appointed to the law review was an indication of high grades.

Tarrytown, New York

HAVING CORRECTED THOUSANDS of student examinations and papers as a history professor at Williams, Columbia and the University of California, I have observed a dramatic change in the quality of both papers and exams.

Today all a student has to do is select a topic or exam question. The Internet will supply, in the time it takes to walk to Baker Library, more information than needed. The student has to organizewhich even the most dimwitted Dartmouth student can do—then write on a fast and facile computer. Another tap on the keyboard and the computer corrects the grammar and checks the spelling. Voila! A perfect paper or one very difficult not to give a very good mark, usually an A-. The minus because the instructor is viscerally opposed to grade inflation.

Santa Barbara, California

As AN ENGLISH PROFESSOR IN THE Pennsylvania state system, I have found that one can hold the line on grade inflation and simultaneously command students' respect, albeit with a somewhat more academically diverse intake of students than Dartmouth's.

One practice I recommend is conferences with students to discuss early drafts of major papers. Conferences let professors point out major weaknesses and strengths prior to grading final versions. A second practice is ungraded journal responses to assigned readings. These reactions help professors indicate to students the quality of their understanding of the material before tests are taken. A third practice is to have students read each others' papers before submission for grading. This helps students judge the quality of their work in a larger context. In all courses I grade on individual merit, not a predetermined curve.

Rightly or wrongly, younger faculty may conclude that they will receive more positive student evaluations if they grade easily. My experience on a university promotion committee made me suspicious of a positive correlation between students' high-grade expectations and highly favorable ratings of professors.

Parental expectations are also a source of pressure. My professorial experiences led me to tell my own children that my primary expectation was that they pass their courses and obtain a sufficiently high grade average to graduate with a bachelors degree in four years. Both went on to complete masters degrees and to careers they enjoy.

Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania

I LEARNED A LOT AT DARTMOUTH, but my grades weren't too hot. I didn't complain then, and I wouldn't bring it up now, except reading about grade inflation got me thinking. I can attest from personal experience to the raw truth of the comments of professor Dana Williams, who said low grades "damage" and "penalize" students. More than 30 years later I still feel the sting. But it's not too late to salve my psyche, and that of others in my situation. If the College retroactively adjusted some of those C+'s into As, my self-esteem would soar.

San Francisco, California

Animal House

I WAS THOROUGHLY AMUSED BY TED Levins article ("Animal Attraction," Mar/Apr), in which he describes how chipmunks needed assistance getting back out of the old Map Room at Baker after climbing in. This resulted in a librarian hanging a homemade rope ladder out the window to assist their escape.

And I thought I was nuts when I tossed a specially marked seat cushion/ life preserver into my swimming pool to help the occasional frog get out.

Boca Raton, Florida

Deans List

I HAVE SEARCHED FOR YEARS FORA satisfying statement about the relationship between good teaching and the teachers personal research activities.This is a huge deal in medical education. I liked Dean Gazzaniga's "leaving the student with an unease about the status of [current] knowledge." ("The Fourth 'R,'" Mar/Apr). That is when the student learns about the Journal of NegativeResults, Unpublished Studies and Projects NotUndertaken.

Evanston, Wyoming

Amazing Grace

THE INTERVIEW WITH SUSAN Conroy '87 ("Continuing Education," Mar/Apr) was outstanding. She is a wonderful example of mature, tested and genuine idealism that continues to be an inspiration to all.

Dallas, Texas

The Good Captain

KUDOS TO MATTHEW MOSK '92 FOR his fascinating, timely and moving piece on Nathaniel Fick ("Back from Iraq," Jan/Feb). The article was compelling from beginning to end. In more than 20 years of reading DAM I have never felt so in awe of a fellow alum, his thoughtfulness, courage and leadership abilities.

Nathaniel's journey to the military, by way of his Dartmouth education-in particular by understanding and mastering the ancient classics and by being willing, unlike his fellow students, to tread the path that he did—leaves one supremely confident both in our country's future and in Dartmouth's continued ability to educate real leaders while ensuring a diverse, competitive and truly stellar student body.

New York City

As A SOLDIER CURRENTLY SERVING in Iraq, I must say that your story on Nathaniel Fick was a very good portrayal of the physical and mental dangers we are confronted with and the sometimes morally ambiguous situations that war presents.

Since graduation I have often won- dered if I have wasted my education. The situation I find myself in, however, has de- manded everything I learned at Dart- mouth and more. The reconstruction of Iraq has taxed lessons learned in the class- room, in athletics, in the fraternity house, in the DOC and from my FSP. A multi- disciplinary approach is required for a multifaceted problem. For the first time since leaving Dartmouth I feel I'm getting my money's worth from my education.

There are some who call the current situation in Iraq the Vietnam of my gen- eration. While I disagree with the nega- tive connotations implied by this, I do believe that what occurs in Iraq during the coming months and years will certainly help define the future of the Middle East and have repercussions across the globe. My generation will be defined in part by the success or failure of this endeavor. If the ending of a dictatorship and the creation of a free society is the Vietnam of my generation, then I am proud to be a part of it.

Captain, U.S. Army Ar Ramadi, Iraq

I RESPECT THE COURAGE OF MY classmate Nathaniel Fick to volunteer to serve in Iraq. I have even more respect for his decision to leave the Marines. In a war with little justification it's hard to motivate the troops or the nation with the ra- tionale, "The good news is, we get to kill people."

Austin, Texas

WITH MORBID CURIOSITY, I FIRST read the article about Captain Nathaniel Fick. With poignant interest I reread it.

The article takes me back to my own experience 35 years ago. Classified "1-A" and having passed the draft physical, I enlisted in the Air Force for officer training. As Fick experienced, many expressed surprise that I, a Dartmouth guy, joined the military: Why didn't I get out of it some way? Unlike Fick, my generation and I volunteered with far less appealing options than those of todays generation. Also unlike Fick, my assignment was to a research lab in Boston, supporting the Cold War rather than the hot war zone far from American shores. I felt then—and more now—that my military work was worthwhile.

My heart goes out to all of the men and women who serve and have served in the U.S. military in the past half cen- tury, because of what happens when we return from active duty. I left the military following my commitment, had a family and led a quiet though happy life. Two years ago, while my wife, a dear young niece and I toured Washington, D.C., we paused near the Vietnam memorial to watch a high school group perform a tribute to veterans. Following some patriotic music and touching ceremony, the announcer thanked each of the veterans. My tears flowed hotly as I realized that this was the first time that anyone in private life had thanked or even acknowledged me for my service. Not my family, not my employers, not my friends, not even I thanked me. I have lived in unconscious silence with the contradictions of my generation, of my life-changing experiences as a young person for the nation and of many life-changing consequences of those commitments. I did not even know to ask for acknowledgment—let alone understanding or empathy.

So to you, Captain Fick, thank you for sharing your story. I hope that in telling it you understand it better, and I hope each of us with variants of your story will learn a little more about our own experiences from your sharing. I hope too that all of us grow slightly in our ability to acknowledge personally the heart-wrenching commitments that very young individuals make as part of military service.

Palo Alto, California

Write to Us We welcome letters. The editor reserves the right to determine the suitability of letters for publication and to edit them for accuracy and length. We regret that all letters cannot be published, nor can they be returned. Letters should run no more than 200 words in length, refer to material published in the magazine and include the writer's full name, address and telephone number. Write: Letters, Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, 7 Allen Street, Suite 201, Hanover, NH 03755 E-mail: DAMletters@dartmouth.edu Fax: (603) 646-1209

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

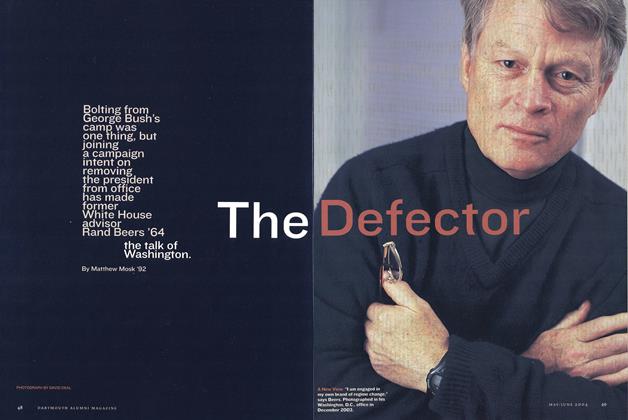

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

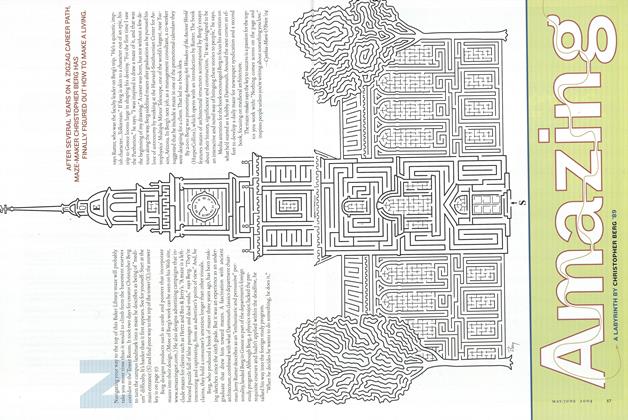

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

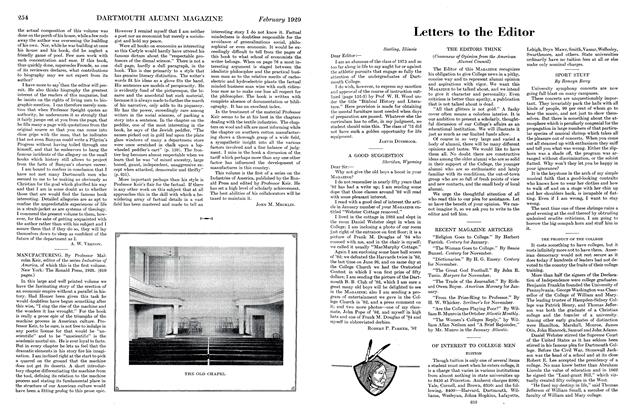

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1965 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorOn Wise Teachers

February 1992 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Nov/Dec 2005