You Can’t Always Give What You Want

When a class project meets the needs of the college, it’s a match made in heaven, but what happens when a class wants to go off the wish list?

May/June 2004 ALICE GOMSTYN ’03When a class project meets the needs of the college, it’s a match made in heaven, but what happens when a class wants to go off the wish list?

May/June 2004 ALICE GOMSTYN ’03WHEN A CLASS PROJECT MEETS THE NEEDS OF THE COLLEGE, IT'S A MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN, BUT WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A CLASS WANTS TO GO OFF THE WISH LIST?

A TREE FOR EVERY CLASSMATE, A FOREST FOR THE CLASS. It was a grand, verdant plan laid out in earnest by the officers of the Dartmouth class of 1967.

The class officers, made up of two dozen or so of the most active members of the class, dreamed up the idea in the summer of 2000: The College would set aside a large swath of land on campus, and there a tree would be planted in honor of each member of the class upon his passing. With a class of more than 650 alumni, the hope was that someday the memorial would grow into a thriving forest....

And then came an obstacle. "There is no place on campus large enough to accommodate a forest."

Sue Young '77 makes this statement with about as much blunt pragmatism as is allowed of a College official charged with coaxing alumni to bankroll the structural and extracurricular aspirations of their ever-thankful alma mater. Young coordinates alumni class donations known as class projects.

If you're just talking numbers, class projects—which are earmarked to fund new or existing College programs—pale in comparison to that other staple of alumni giving, class gifts. Class gifts, which flow directly into the Colleges general operating budget and its capital campaign, are the result of massive fund-raising efforts undertaken by different classes. Often they yield contributions of hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars; in 2003, for its 25th reunion fund-raising campaign, the class of 1978 donated a gift of $14.8 million.

Class projects, meanwhile, must come from omnipresent class dues treasuries—not fund-raising campaigns—and are capped at a relatively paltry $100,000 per year (a limit set in the early 1990s amid concerns that overly generous spending on individual class projects would, in turn, lower donations made to class gifts).

Still, class projects provide fiscal relief for the College budget; in these days of shrinking endowments and budget cuts, that's no small feat. And so Young is in a precarious position. She must resolutely guide class leaders in determining how to spend thousands of dollars without pressing so much as to turn them off to the process entirely. Her end goal: To settle on class projects that satisfy both alumni wishes and College needs.

It just so happens that the College needs a lot, everything from benches and (stand-alone) trees to athletic recruitment programs and hearing-enhancement kits. Ensuring that these needs are matched with alumni donations is no walk on the Green—it takes time, diplomacy and organizational skills so refined they could put Dewey and his decimals to shame.

Every couple of years, after surveying all Dartmouth departments—academic, administrative and otherwise—the Colleges Office of Alumni Relations updates its projects "wish list," an extensive 40-page catalog enumerating the myriad ways alumni funds could be spent (see page 54). If read aloud, it sounds like the beginning of a MasterCard commercial: "Fund a student intern to serve as the Composition Centers head tutor...$3,000; Refurbish and provide new furniture for Tom Dent Cabin...$5,000; Newsets of bleachers for outdoor tennis matches...$9,500."

Making administrators, faculty, students and alumni happy: priceless.

Most classes that fund projects time them to coincide with major class reunions. They often use the catalog, which is mailed to them upon request, to help them determine what to fund. But not everyone wants to stick to the list.

According to class president Samuel Ostrow '67, alums who graduated in the same tumultuous times as he did are especially prone to ignoring the list and originating new, unconventional projects.

"Classes of the 1960s are generally more inclined to choose their own things to do. It's reflective of class spirit and the times we went to Dartmouth," he says. "At the end of the 1960s, it was do your own thing,' whatever the hell that meant, so the questioning of authority, in one way or another, is still within our class."

He and fellow class officers first approached Young with their forest idea, most definitely not found on the wish list, in 2000. Young had initial concerns about the scope of the proposal, which she didn't hesitate to share with the officers. "It's my job to give them advice and say, You may want to think of this [project] in a different way, cause it probably won't fly,' " she says.

Young nonetheless explored the possibility of a memorial forest, conferring with other College officials and departments, including Facilities Operations & Management. FO&M reaffirmed her concerns: The place that Daniel Webster so famously referred to as "a small college" was, indeed, too small for the class of 1967's great plan. Nowhere on the College's 200-acre main campus nor on the College Grant was there room for a planted forest hundreds of trees strong.

As Young saw it, the only way to curb the class' disappointment was through a word she finds herself using quite often in her line of work: compromise. She would seek to work with class officers to find another, smaller memorial that could be erected within the campus limits.

As in any negotiating process, the specter of diplomatic failure loomed; there was, after all, that independent Sixties spirit to contend with. "We tend to go our own way and not take direction from anybody," Ostrow admits. There was also disdain for some of the projects suggested by the College. "There was a proposal to [fix] the boilers at Moosilauke," Ostrow notes with some bemusement. "We said no thank you."

But by November 2000 Young came up with a proposal that did hold some appeal for Ostrow and his compatriots: a memorial grove to be planted in front of the Dartmouth Outing Club house. It would be like a forest, only smaller.

Ostrow explains the idea fit because his class' original goal had been to provide a living memorial to its members. "We accepted [the proposal] very happily," he says.

With the class giving its okay and, of course, its cash—roughly $20,000 that was spread over two years so as to comply with the class projects spending cap—work on the grove began that following May and was completed in time for the 35th reunion in 2002.

Bruce Pacht '67, the class reunion chair, coordinated the actual planting of the trees—six full-grown eastern white pines and two shadblows—placed in the shape of an oval. He is pleased with the results of his efforts. "It's in a good location, and it's pretty visible," he says.

"It's very peaceful," says Michael A. Choukas '77, who passed the grove one recent afternoon on his way to teeing off at the near-by Hanover Country Club. "I just hope I don't hit any shots into it."

The risk of wayward golf balls notwithstanding, this class projects story seems to have what Young says is a typically happy ending. She estimates that about 50 alumni classes participate in class projects every year and that "most of the time, the classes are very amenable to variation on what they want to do." As for the other times? Well, let's just say Young is reluctant to share those stories.

Meanwhile, class of 1967 officers don't have plans for any new class projects or College donations just yet. But that could all change by the time of their 40th reunion in 2007. It's an event for which "the College really takes an interest in getting you to return to campus," Pacht says. "I hear that's when they have you put Dartmouth in your will."

ALICE GOMSTYN, a former DAM intern, is a staff writer/or The Providence Journal in Providence, Rhode Island.

"There was a proposal

to [fix] the boilers at Moosilauke. We said no thank you." -SAMUEL OSTROW '67

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

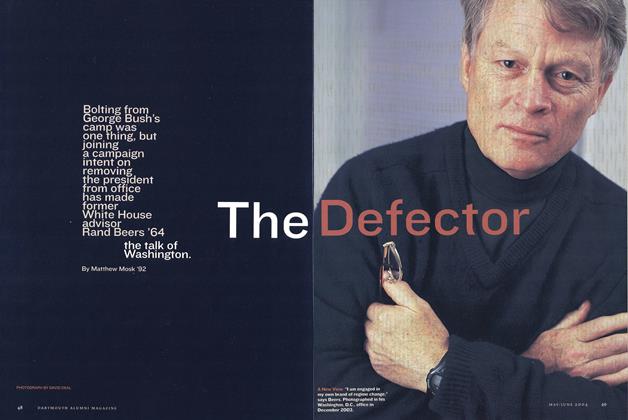

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

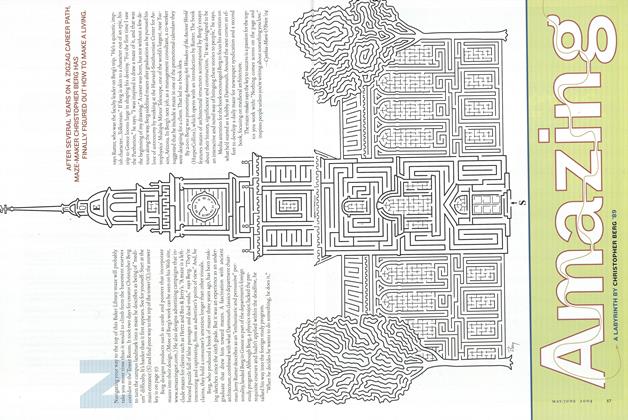

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionIn Praise of Class Notes

May | June 2004 By James Zug ’91

ALICE GOMSTYN ’03

Features

-

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureProfessional Schools

April 1975 -

Feature

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

NOVEMBER 1984 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

OCTOBER 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

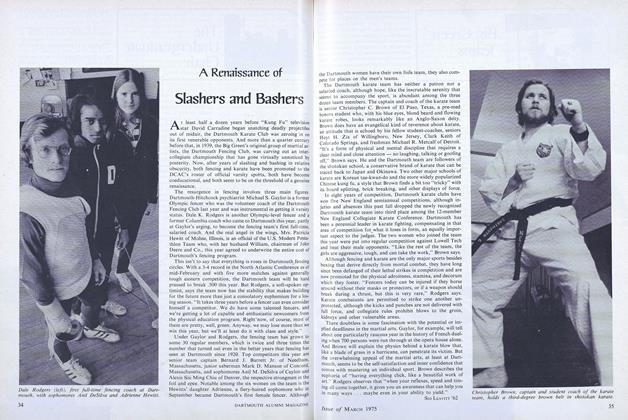

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62