The Defector

Bolting from George Bush’s camp was one thing, but joining a campaign intent on removing the president from office has made former White House advisor Rand Beers ’64 the talk of Washington.

May/June 2004 Matthew Mosk ’92Bolting from George Bush’s camp was one thing, but joining a campaign intent on removing the president from office has made former White House advisor Rand Beers ’64 the talk of Washington.

May/June 2004 Matthew Mosk ’92Bolting from George Bush'scamp wasone thing, but joininga campaignintent onremovingthe presidentfrom officehas madeformer White House advisorRand Beers '64the talk ofWashington.

A YEAR AGO LAST MARCH, as his boss prepared to go on national television and give Saddam Hussein 48 hours to surrender, Rand Beers had finally reached his tipping point.

The nations top counterterrorism official crossed the parking lot that separated his office from the White House, stepped under a canopy that led into the West Wing, up a flight of stairs and into the office of National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice.

The mood in the room was tense. Rain pelted the window and washed down across neighboring Lafayette Park.

"Is this about the Iraq war?" Rice asked. "No," Beers fudged. "I just can't do this anymore. I can't bring the kind of commitment and dedication to the job that it warrants, and I can't ask people working for me to bring that commitment if I can't."

"Okay," Rice said, rising stiffly from the couch. "I'm sorry to see you go."

The two-minute conversation marked the final moments of a long career in the shadows—fighting communism in the rice paddies of Vietnam, the drug war in Colombia's coca fields, and terrorism from a Washington office that is secured behind three layers of electronic locks and a solid steel door. It also marked the coming of a new career for Beers, one that would place him under the searing spotlight of presidential politics and deliver him from the life of quiet government service that had been his family's calling for three generations.

Rand "Randy" Beers, 60, was born within a few miles of the lofty corridors of power that he later strolled as an adult. His grand- parents had moved from Vermont to the District of Columbia in 1906 to conduct research at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But as the stepson of a naval officer, Beers was raised on the move, spending first grade in Jacksonville, Florida; fourth grade at Pearl Harbor; sixth grade in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania; and 10th grade in Newfoundland.

Dartmouth was his second choice for college (he didn't get in to West Point), and when he drove north to Hanover in i960, it was with plans to learn enough math and physics to become an astronaut. As a member of ROTC, he owed time to the Marines upon graduation, shipped off to Camp Lejeune and, not long after that, to Vietnam.

Beers did two tours of duty in Vietnam—the second one voluntary because he wanted to see combat and hadn't. "I was young and immortal and, in retrospect, kind of foolish," he says now. On that second tour, Beers' rifle company stumbled into only one real firefight, with a North Vietnamese battalion that had been camped just 500 meters from their position on the Danang perimeter. They engaged over a series of days, and the bloody experience left a lasting impression that would become relevant to Beers' life decades later, when a new administration would be marching double-time toward war.

"I came home from Vietnam feeling like the military had been misused, and took a lot of crap for something the president alone had basically decided to do," Beers says. "I wanted to do the kind of work that would ensure the American military wasn't put in that position ever again."

That's how he wound up at the State Department, first working with NATO, then in the bureau of political military affairs and then as the head of the nation's effort to combat drugs and terrorism under presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Beers was in the Presidential Palace in Lima having breakfast with Colin Powell and Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo when an aide passed a note to Powell letting him know a plane had struck the World Trade Center.

Within the year Bush had named Beers the nations senior director for combating terrorism, a grinding job that required him to review 500 pieces of threat information every day. He says a typical mix included suspicious surveillance of a nuclear power plant or a bridge, a person caught by airport security with a weapon, an airplane flying too close to the CIA, a tanker truck—that might contain a bomb—crossing the border and heading for a city, an intercepted phone call between suspected terrorists. Most of the top-secret reports, channeled into his office from the White House Situation Room, never panned out.

Beers' long days wouldn't end when he drove home to his apart- ment in northwest D.C. A special phone installed in his bedroom could ring at any hour with reports of an imminent threat or on-going attack, and often it did.

Beers' wife, Bonnie, says she could see her husbands enthusiasm start to wane: He would come home frustrated, and not just because of the workload. "His vision of what might be possible became tarnished by the president's lack of attention to issues he felt were urgent," she says.

The realization he had to quit crept up on Beers slowly. "The conflict was between serving the president and being asked to do something I just didn't agree with," Beers says. "I felt the Bush team was making us less secure, not more secure. And the longer I sat and watched, the more concerned I became."

At first Beers sent word to Rice that he thought the administration was losing focus and said he was considering leaving. But nothing changed.

Beers intended to leave the administration quietly but it didn't work out that way. A week before his final meeting with Rice, he had lunch with Jonathan Winer, a former State Department colleague who had moved on to work on John Kerry's presidential campaign. Beers broached the idea of his joining the effort, too. He had never worked on a campaign but did have a history of voting for Democrats.

"I discouraged him at that point," Winer recalls. "I told him that campaigns are for people in their 20s, maybe 30s, but that they are grubby and relentless and wear you down with a day-to-day grind."

Beers was hardly deterred. With enough government service behind him to qualify for a pension, he was willing to work for free. He said he'd lick envelopes if necessary. He wanted to join.

Shortly after Beers did so, he met Kerry for the first time. Both were at a Washington campaign fund-raiser, and the two Vietnam veterans connected. The next day Kerry announced that Beers would be his senior foreign policy advisor. Beers' turnabout was seen as a staggering event inside the Beltway, where such acts of disloyalty make rich fodder for pundits and insiders.

"I can't think of a single example in the last 30 years of a person who has done something so extreme," Paul C. Light, a scholar with the Brookings Institution, told The Washington Post. "He's not just declaring that he's a Democrat. He's declaring that he's a Kerry Democrat, and the way he wants to make a difference in the world is to get his former boss out of office."

Kerry's team vowed to make the most of Beers' arrival. They capitalized on his intimate grasp of the threats facing the nation and traded on his turncoat celebrity, teaming him up for fundraising events with former Ambassador Joseph Wilson, another Bush defector, who switched sides after his wife was outed as a CIA operative.

Beers says he's taking to the campaign. He works in the drab basement of a nondescript brick row house on Capitol Hill. "Kerry for America" posters decorate the otherwise naked white walls. He and five other volunteers who report to him tap talking points and speech ideas into the laptops that they have propped on folding tables. The only other "furniture" in the place is a coffeepot.

The man who one day could head the National Security Administration—or serve as the nation's secretary of state—comes into work wearing brown cords, a turtleneck and a knit sweater, and sits with his sneakers up on a desk, musing about the role the United Nations should play in Iraq. "I'm engaged in my own brand of regime change," Beers says.

He smiles broadly at the sound of that, and says his life has been different since the moment he walked out of Rices office. "I was free," he says. "When I went home that day, I can't remember exactly, but I'm pretty sure we popped champagne."

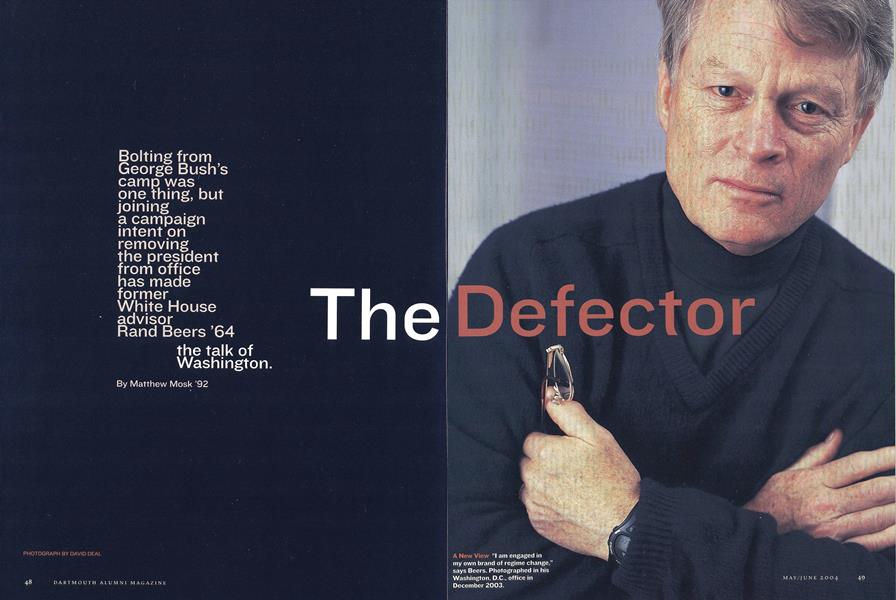

A New View "I am engaged in my own brand of regime change," says Beers. Photographed in his Washington, D.C., office in December 2003.

Beers (left) confers with his fellow Vietnam vet—and new boss—John Kerry.

Contributing editor MATTH EW MO S K is a metro reporter for The Washington Post He wrote DAMs Jan/Feb cover story, "Back From Iraq."

"I came home from Vietnam feeling like the military had been misused. I wanted todo the kindof work thatwould ensurethe Americanmilitarywasn't put inthat positionever again."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

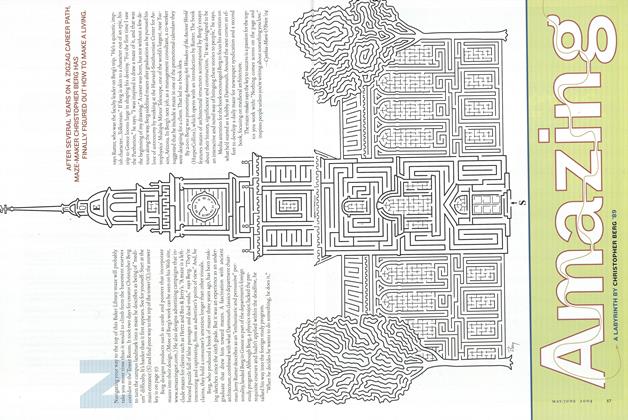

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionIn Praise of Class Notes

May | June 2004 By James Zug ’91

Matthew Mosk ’92

-

Cover Story

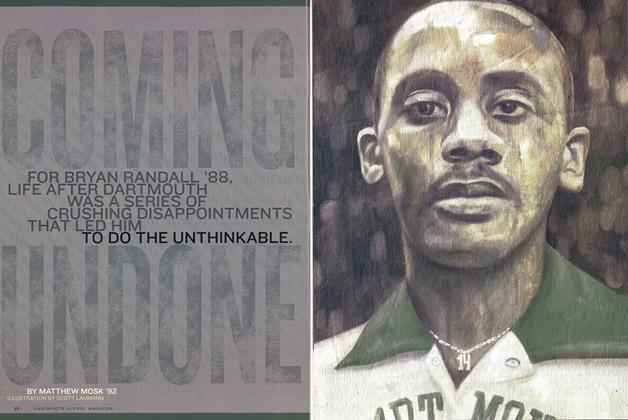

Cover StoryComing Undone

Jan/Feb 2005 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Article

ArticleMarines Go Green

Nov/Dec 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureOne Step at a Time

Sep - Oct By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBSewing Seeds of Conscience

Jan/Feb 2013 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEThe Zinger

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By Matthew Mosk ’92

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

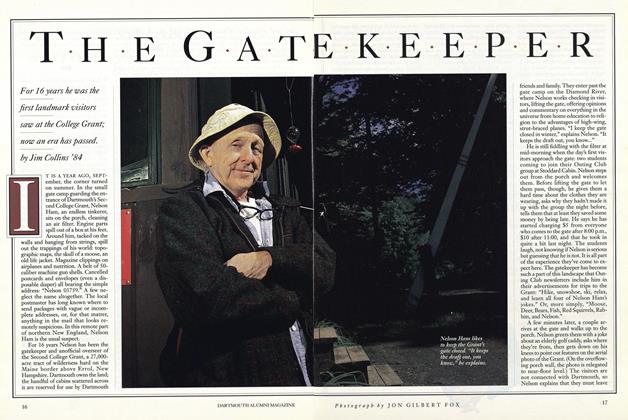

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Features

FeaturesJoseph Campbell, class of 1925

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Marley Marius ’17