Capitol Steps

Thanks to a Rockefeller Center training program offered in Washington, D.C., Dartmouth students are poised to make the most of internships around the world.

May/June 2006 ALICE GOMSTYN ’03Thanks to a Rockefeller Center training program offered in Washington, D.C., Dartmouth students are poised to make the most of internships around the world.

May/June 2006 ALICE GOMSTYN ’03Thanks to a Rockefeller Center training program offered in Washington, D.C., Dartmouth students are poised to make the most of internships around

he world

Chris Galiardo '06, Brian Donaldson '07, Jackie Olson '07, and Hillary Abe '08 are jetting across two continents for a whirlwind, three-week vacation funded by the Dunne Foundation, which has generously provided the student group with $25,000 for travel and other expenses. The catch is that the would-be globetrotters must spend the exact amount allotted—no more, no less.

The group isn't worried. Airfare, they figure, will consume most of their money, but that's okay. They don't plan on spending much on accommodations. They'll stay in hostels and live out of their backpacks. But they're not packing their bags just yet—the Dunne Foundation, the travel funds and the planned trip are all fake. The students are participants in Civic Skills Training, a five-day Dartmouth program based in Washington, D.C., and organized by the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy.

Born in 2004 out of a larger Rockefeller Center effort to increase student engagement in public service and public policy, the program is largely the brainchild of Matt Dunne- former head of AmeriCorp/VISTA and a Vermont state senator running for lieutenant governor—who was hired that year as the centers associate director for public impact.

Former Rocky director Linda Fowler asked Dunne to figure out how Dartmouth could better prepare students for careers in the nonprofit and public sector, and he immediately reached out to students and faculty for an answer. What he found was a glaring disparity between what College organizations were investing in funding student internships—for example, covering living expenses for students working away from campus during off-terms—and what they invested in training students before the fact.

"I was hearing from students who said, 'You know we don't feel like we're ready when we show up at an internship. In fact, we really figure out what we should be doing by week nine out of ten,' " Dunne says.

Organizations such as the Rockefeller Center and the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding "have all been funding internships for a long time," Dunne says. "What became very clear very quickly was that we could get a lot more out of that investment if we spent five days really training students how to take the best advantage of that internship, how to make the biggest difference and how the different organizations they're working with actually connect together."

The primary objective of the program is to help students hone the skills necessary to survive and succeed in public service. It's training they might not get elsewhere, the programs organizers say.

According to Dunne, civic and nonprofit organizations are "notorious for under-investing in the early stages of a persons career and employment."

Cash-strapped nonprofits, he explains, may consider training in various professional skills as an "extra" they can't afford. Interns, especially, may have trouble finding fulfilling work and are instead relegated to picking up the boss's coffee—a task that might frustrate even the most determined fledgling activists. They have a tremendous desire to improve the world around them and for things that aren't just in the pursuit of their own financial rewards," says economics professor Andrew Samwick, the director of the Rockefeller Center. "But I don't think they necessarily know what steps to take."

Each program participant—about 12 to 16 per session—is expected to initiate a project during a leave-term internship following the program. Ideally, the project s results will continue to benefit an organization long after the student s internship has ended.

To help students get that project off the ground, each session features training in skills such as project management, fundraising and public speaking. It also encourages students to explore how different organizations relate to one another and how to capitalize on such connections.The exercises are guided by Dunne, Rockefeller Center coordinator Karen Liot Hill '00 and various guests such as Jean Carrocio, a consultant specializing in organizational human development. Alums from the D.C. area are involved as panelists.

So far the training is working. Students from the previous three Civic Skills Training sessions have reported success with past projects ranging from working on a Web site for the World Health Organization to an after-school knitting program for at-risk children in Ecuador.

"Our hope is to be able to help individuals going into those sectors build a framework to be able to do something," Dunne says.

Samwick says there are plans to expand Civic Skills Training in the future. To serve the relatively large numbers of students who take on summer internships, the summer session may soon include double the students participating in other sessions. There is also talk of independent-study projects by students based on their internship experiences and perhaps the founding of an on-campus civic skills program for students doing civic service work at or near Dartmouth.

A students odds of getting into training sessions may change in the future as well. To qualify for the program, students must have already secured a leave-term internship following the program. Students generally apply to take part in Civic Skills Training in concert with their applications for internship funding from the Rockefeller Center and other campus organizations. While the center hasn't yet had to turn applicants away for lack of space, Dunne expects the application process for Civic Skills Training to grow more competitive.

The programs total operating costs run about $150,000 annually. The costs not covered by the New York-based Surdna Foundation, which awarded the Rockefeller Center $75,000 in 2004 and again in 2005, come out of the centers own budget. As organizers look to the programs third year, Samwick says the Rockefeller Center will re-apply for another Surdna grant, find other sources of funding and possibly find Civic Skills Training a permanent home in the Colleges budget.

The globetrotters' trip-planning exercise in the Civic Skills Training session is run by Carrocio. This particular exercise focuses on helping students identify their strengths and weaknesses. The 13 students taking part are asked to divide themselves into groups based on their individual working styles.

A chart with descriptions of four types of working stylesnamed after the cardinal directions—serves as their guide.

The "North" group is described as assertive and decisive. The "West" group is considered more introspective and practical. The "South" group relies more on intuition. And the "East" group will be made up of visionaries who see "the big picture."

The decision to have students plan a vacation—rather than, say, a relief mission or something else more relevant to public serviceis a strategic one. Carrocio says that the fun and excitement of planning a trip will keep students from over-thinking the activity and over-analyzing their participation. And since it's unlikely that any one group memberwill be identified as an "expert" in vacation-planning, there's a better chance that each person will "participate naturally."

During the exercise, Carrocio says, students should be asking themselves how they approached the activity, what they contributed to the planning, what they could learn about their strengths and what they could learn about others.

"It's all about you knowing yourself," Carrocio tells the group. "What matters is 'Can you walk away thinking about yourself and one another in terms of strengths and areas you might need to manage in terms of weaknesses?' "

The East group—Donaldson, Olson, Abe and Galiardo—is diplomatic in its planning. Asked where he or she wants to travel to most, each member comes up with a different answer. But instead of choosing one locale over another, the group decides together to visit all four places, making sure to limit their time and spending at each destination.

When it comes to its presentation the East group seems to embody its "visionary" categorization. The other three groups choose one or two destinations and, on large white sheets of paper, list their itineraries, planned activities and expenses. The East group writes down its four destinations and draws long arrows in between them. Big picture, indeed.

While part of the training is dedicated to helping students get to know themselves, a major recurring theme during the training is the importance of getting to know other people—in other words, networking. It is the most controversial subject covered during the program and one that meets with some resistance.

Megan Hamilton '06, who participated in the March 2005 training session, is at the September session to assist Dunne and Hill. She remembers well her own reluctance to tackle the subject during her time as a civic skills trainee. She and her peers, she says, initially viewed networking as a "seedy" process.

"We felt we weren't going off into the corporate internships, so why should we be learning all these tactics on how to booze and shmooze?" she says. "This is not who we are.This notwhy we chose to go into an NGO or a nonprofit." Hamilton gives voice to a mentality that Dunne and Hill are fighting against.

Says Dunne: "There seems to be an impression that understanding strategies of how to be effective is somehow cheating." "Or selling out," adds Hill. They make the case to students that those in the nonprofit world can use networking to accomplish worth while goals.

Before the networking discussion, students are assigned readings that illustrate the value of the process. One article describes how a Chicago woman named Lois Weisberg met people in random places (on the street or a train) and not-so-random places (parties at her home). Weisberg stayed in touch with them, introduced them to other people she knew and used her connections to start projects such as an arts program for low- and middle-income children.

The article seems to leave students with positive impressions of networking. "It wasn't always about how Weisberg could benefit from relationships," says Alex Leonard '07. "She brought together a lot of people for good causes."

The relationships weren't based on long-standing bonds, notes Christine Pfeiffer '07. "When I think of networking, I think it's with someone you're really close to," she says, "but it can be with someone who you've had a five-minute conversation with."

The article doesn't win everyone over. Not everyone can throw parties like Weisberg did, says Abe. Many people, argues Rachel Bloch '07, simply aren't in the position to network. They don't have time to meet and forge relationships with other people—they're busy working to support their families.

"It really bothers me because it's so unfair," she says. "We sit here and learn about this while the majority of the United States can't because of poverty."

Dunne counters that networking can reach across economic strata. "There are networks that aren't just attached to large dollar signs and significant titles," he says. Nadia Khamis '07 seems to agree. Part of networking, she says, "is connecting to people in different worlds."

During the workshop the students have plenty of opportunities to hone their networking skills—mainly with Dartmouth alumni. On the second day of training they attend a panel of Dartmouth alums who work for or with lawmakers, including Vanessa Green '02, an analyst on the Senate budget committee, Pherabe Kolb '94, of the Smithsonian Institute Office of Government Relations, David Dawley '63, a consultant to businesses and nonprofits, Kevin Davis '94, an attorney in the U.S. Senate legislative counsel office, and Superior Court judge John Mott '81.

On the third day, after sessions that included a speech by Matthew McDonald '00, associate director of communications for policy and planning for the White House, and a panel discussion involving New America Foundation president Ted Halstead '90 and Sarah Jackson-Han ' of Radio Free Asia, they're off to an alumni reception organized by the D.C. Dartmouth club and featuring a speech by former Assistant Secretary of State Bobby Charles '82.

On the fourth day there's a dinner with young alumni who work in and around government, including Ben Correa '04, Susan Edwards '04, Elena Klau '03 Joshua Marcuse '04 and Sean Oh '04.

These events cap eight-hour days filled with lessons, discussions, presentations and occasional visits with a D.C. politico such as New Hampshire Congressman Charles Bass '74. After all the meet-and-greets, there's little time for leisure: Some students go straight to their hotel rooms to do homework assignments and prepare for the next day.

The perpetual hustle and bustle is not without consequence. By the third day some are using the 15-minute breaks between lessons to take power naps.

No one could say they weren't warned. At a dinner before the program formally began, Hill told students it would be "an intense week."

"You've signed up for something that's going to take a lot of investment, "she said, "but I promise you will reap great rewards."

Months later, many of the participants could attest to the truth of Hill's words. Halfway through her 10-week internship, Karem Coronel '07 pointed to myriad ways the program helped her with her work at a Mayan women's organization in Chiapas, Mexico. Topping her list was the program's focus on public speaking. On each of the five days students were required to give short speeches on subjects relevant to the nonprofit or civic work that interested them. Following each speech students received constructive criticism from their peers as well as Dunne and Hill.

"That was the most productive part of the workshop for me," Coronel says, "I was able to conduct my interviews in a professional manner, I was able to portray confidence I never thought I had."

For Rahul Sangwan 'O7 one of the programs most valuable lessons was how to work with your boss to meet both your goals and his—also known as "managing up." This proved helpful during his internship at the U.S. embassy in London. "Especially in a stressed environment, getting to know and understand your supervisor is crucial to establishing a healthy working relationship," he says.

For Leonard the memo-writing skills she polished at Civic Skills Training came in handy when it came time to write briefings for the Washington, D.C., office of Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy. The programs emphasis on networking also proved useful. "There are a ton of opportunities to network. You can do it in the hall, you can do it a party," she says. "It felt a little bit awkward at first, but I think it's part of life on the Hill. You just have to keep practicing. Be personable and be yourself. That's how I do it."

Graduates of the September program have completed a variety of projects, including a briefing on organized crime and terrorist activity by Sangwan, a Web site for future interns at the D.C.-based advocacy group Feminist Majority by Danielle Strollo '07 and a handout to accompany a video on depression for psychiatric patients at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center by Bloch.

What's next for civic skills grads? For Strollo and likely many others, the answer is more hard work. Strollo says she is considering law school and using her legal expertise to work for civil rights and women's rights. It won't be the most lucrative endeavor, she says, but it's something that matters to her. "I'm going to live on passion and bread for the next 20 years of my life," she says.

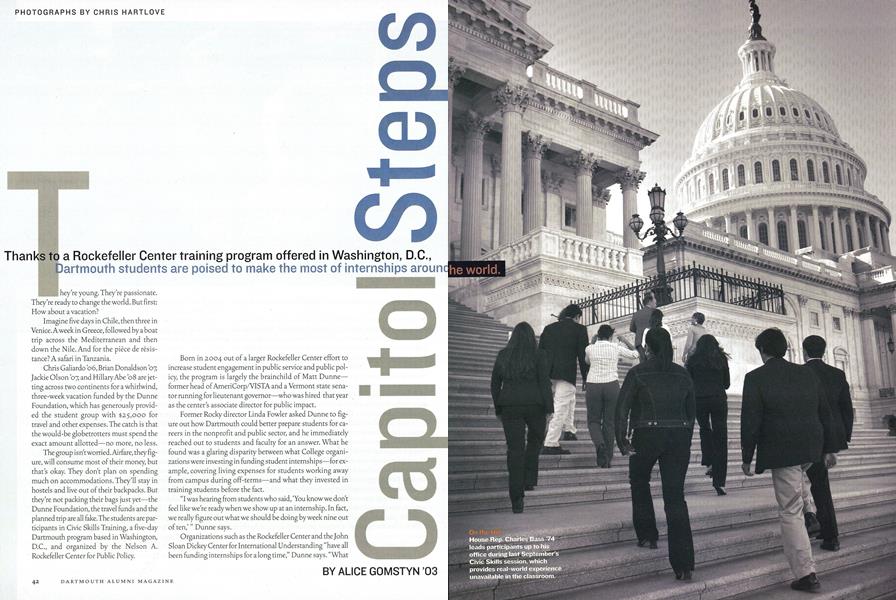

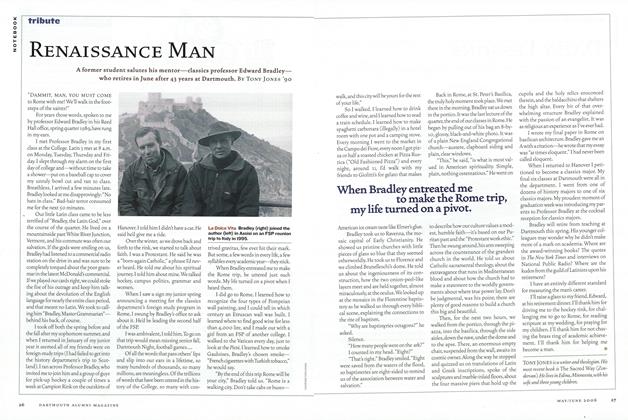

House Rep. Charles Bass '74 leads participants up to his office during last September's Civic Skills session, which provides real-world experience unavailable in the classroom.

Faces of the Flaws Clockwise from lower left, opposite page: Brian Donaldson '07, Amanda Brown 'O7 and Hillary Abe 'OB review study materials; Brown and Christine Pfeiffer '07 in one of the training discussion groups; interns enter the office of Congressman Charles Bass '74; Bass addresses the students; a discussion group in progress.

Rahul Sangwan '07

Chris Galiardo '00

The primary objective of the program is to help students hone the skills necessary to survive and succeed in public service.

While part of the training is dedicated to help a major recurring theme is ing students get to know themselves, the importance of getting to know other people.

ALICE GOMSTYN, a former DAM intern, is an education writer at thedaily Journal News, which covers Rockland, Westchester and Putnam Countiesin New York. She lives in Hohoken, New Jersey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

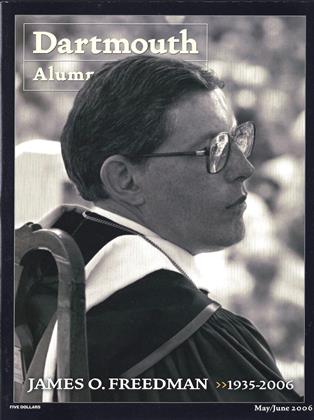

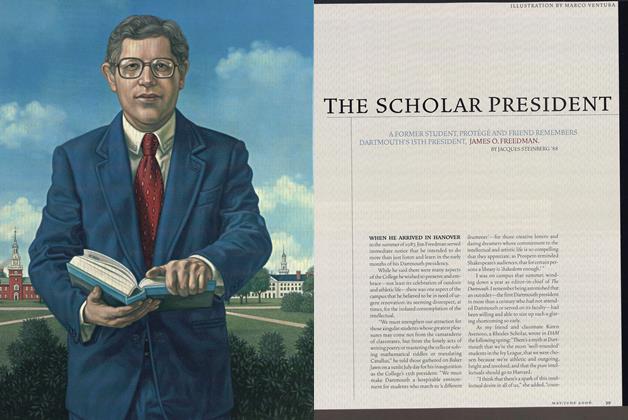

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May | June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

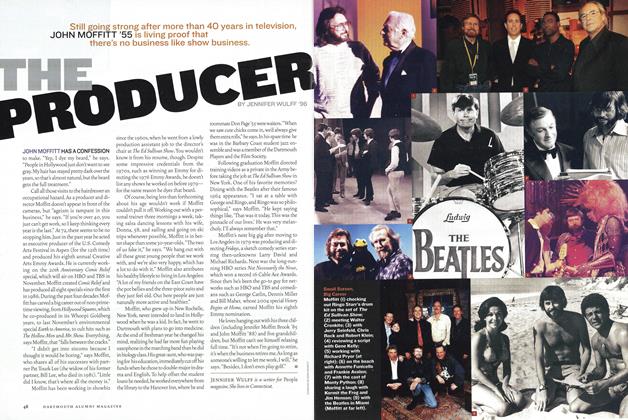

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleRenaissance Man

May | June 2006 By TONY JONES '90

ALICE GOMSTYN ’03

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

MARCH 1990 -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

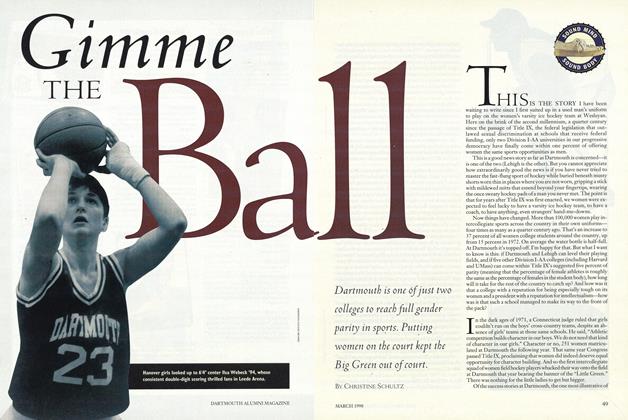

FeatureGimme the Ball

March 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Feature

FeatureHome, Home on the Plain

OCTOBER 1982 By Jeffrey Boffa -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GREEN UP YOUR KITCHEN

Jan/Feb 2009 By JENNIFER ROBERTS '84