The Stages of Life

An unforeseen role leads to an unexpected—and unforgettable audience.

Mar/Apr 2006 Nell Shanahan ’99An unforeseen role leads to an unexpected—and unforgettable audience.

Mar/Apr 2006 Nell Shanahan ’99An unforeseen role leads to an unexpected—and unforgettableaudience.

WHEN I GRADUATED FROM Dartmouth on a bright and sunny morning in June of 1999,1 thought I was invincible. It seemed to me then that anything was possible and that the world was my oyster. Thanks to the inspirational teaching of professors Fred Berthold 45, Hans Penner, Ron Green and Charles Stinson (in whose class I first read what remains to this day my favorite book, Fear andTrembling), I was able to graduate cum laude with a degree in religion and with a great love for Kierkegaard. Despite all of this, I decided that I would try my hand at acting professionally. I had starred in plays and musicals throughout high school and college, right up until my senior year at Dartmouth, when I took on the character of Catherine in The Foreigner and thought I had found my passion. I thought I had discovered what made life worth living. And so I tried to make a career out of that passion. I bought a one-way ticket to L.A., got some headshots and an apartment (in that order), and promptly fell apart at the seams. Life in Hollywood wasn't at all what I expected, and after my first onscreen appearance as a waitress in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (wearing nothing more than silver-colored dental floss), I knew this profession wasn't for me. It felt as if I was really living only for myself, even as I was wishing I were actually somebody else—someone prettier and skinnier and with eyebrows that didn't slant down in the wrong direction or with a nose that wasn't so darn crooked.

It wasn't long before I started rethinking what I was going to do with my life. And not much longer before I started thinking about religion and philosophy again, and contemplating a return to the field that sustained me throughout my years at Dartmouth, before I impatiently overlooked (or underestimated) that sustenance for a life in the spotlight.

I still think about these things—now, as a second-year graduate student in ethics at Yale Divinity School. Although there was always a voice inside me that considered pursuing a graduate degree in religious studies, I would have probably called anyone crazy who predicted on my graduation day that I would go to divinity school in the fall of 2004—let alone work as a hospital chaplain during the summer of 2005. Yet, it happened. And, boy, am I grateful it did.

Martin was the first patient I visited as a hospital chaplain in New York City. From the moment I met him, I liked him. He was gentle, kind and wise beyond his almost-90 years. During the first few weeks of our visits together we didn't talk much about religion or faith (which was, at first, a great relief, especially after long and emotionally draining days of prayer at the bedsides of patients very near to death). Instead, it was love and Brooklyn that occupied most of our time. He would tell me stories about his life with his wife, Judith—his "diamond"—and the many trips they took together to places such as Poland, Israel and Hungary, when they were not at their home in Brighton Beach. My favorite stories were about his love for Judith. During one of our first visits he told me about the day they first met, when Martin saw Judith at the other end of a pool and swam over to introduce himself. He said he had never left her side since. After asking me about my own love life and whether I would marry, he said that marriage was work and the secret to a lasting one was to hug and kiss each other every night before falling asleep. He said he hoped my life would be fortunate that way. The way his had been.

Within weeks Martins health began to deteriorate. He began to have greater difficulty breathing and was transferred more than once to the medical intensive care unit. Things continued this way until one day when he told me that he felt as though he was floating above his hospital bed. He said he couldn't feel his bottom anymore and sometimes even felt as though he was on a ledge and about to fall off. He was also losing his appetite, and was getting frustrated when anyone tried feeding him.

Not too long after these episodes I ran into Judith, who said she had just been told by the doctors that it was only a matter of days, perhaps even hours, before she was going to have to let Martin go. Upon seeing her crumbling frame, all I could say was that I was there and would remain by her side until the time came for her to say goodbye. As an interfaith chaplain I was willing and wanting to offer spiritual and emotional support to Judith as I did with all of my patients, no matter their faith tradition. Yet, as a Unitarian, I knew there were certain limits as to what kind of spiritual support that could be. Although I could suggest prayer, I knew my relationship to Judith up until that point had been largely one of a friend, so I did not want to risk making her feel uncomfortable by offering to pray. She had grown up Jewish Orthodox and was now Conservative. I couldn't imagine how I might feel hearing a lapsed Catholics Unitarian prayer, if I were she. I decided to simply offer my comfort and support while letting her know that if she wanted a rabbi, she should let me know.

During the next several hours we just talked. I told her about the first time I met Martin, when he told me to "just be the way you are," and she told me about the first time she met her "shana mensch" (Yiddish for "beautiful person") when he swam across the pool to say hello and couldn't say goodbye. The story of their first meeting was special to them both. We continued to talk until the chief resident came into the room to let us know that it was unlikely Martin would make it through the night.

That evening Judiths family arrived at the hospital to await the final goodbye. After each of them had spent some time with Martin I encouraged them to take Judith to get something to eat and assured them I would wait with Martin until they returned. Alone with him then, I pulled up a chair to Martins bedside and reached out to hold his hand. Although he was still struggling to breathe, the doctors had initiated a morphine drip, so he was almost entirely unconscious of his state or surroundings. Knowing that his body was likely warm, I reached out for a cool washcloth to wipe his forehead and eyelids. As I touched his face, I whispered, "Do you know you are my favorite? You are my favorite, you know. You have been so brave, and I am so proud of you, Martin. I want you to relax now. Just rest." As I continued wiping his face, I could feel my eyes watering and my vision begin to blur. I was the chaplain and he was my patient, but the relationship between Martin and me had become so very much more. We had become friends, and he had become my favorite. I didn't want to let him go.

After wiping Martins forehead again, I reached down for the Jewish prayer book that one of my colleagues, a rabbi, had given me earlier in the day, when she suggested I recite the Shema to Martin in his final hours. Although I didn't know Hebrew, I decided it was appropriate to recite this prayer, even if only in English, as I knew how much Martin's heritage meant to him and how much of his identity was rooted in being Jewish. I reached down to take his hand in mine and began to recite: "Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord Eternal. Blessed is the glory of God's dominion, forever and ever." I repeated it again, and then once more as Martin's body slowly started to give up its fight.

Just then Judith's family returned to the room. I moved away from the bed to give them some space and watched as Judith quietly moved to Martins side. She reached down for Martins hand, started kissing his forehead, and began to speak: "My delicious Martin, my shana mensch. You are my shana mensch, Marty, and you're leaving me now, do you know you're leaving me? You are leaving me now." And then, within seconds, he was gone. The struggle was finally over.

Although I only knew Martin for a summer, I continue to feel consumed by his passing and trust that these feelings of loss and gratitude won't go away anytime soon. In all likelihood I will experience them again, as a resident in hospital chaplaincy after graduating from Yale next spring. A life among "beautiful persons" I will seek once more, only this time it will be different than it was in L.A.

"I would have probably called anyone crazy who predicted that I would go to divinity school."

NELL SHANAHAN will graduate in May2007. She has changed the names of her patientand his wife to preserve confidentiality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

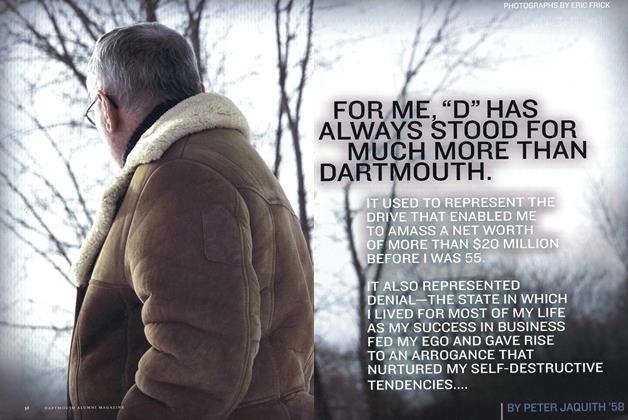

Feature“D” is for Denial

March | April 2006 By PETER JAQUITH ’58 -

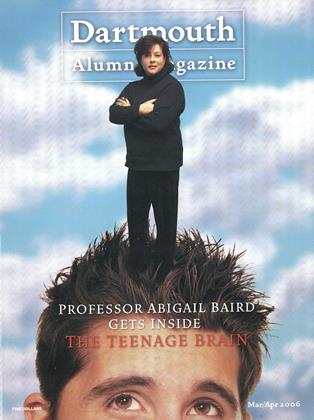

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

March | April 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2006 By Paul Stone '60 -

Sports

SportsThree Times a Coach

March | April 2006 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

March | April 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYAnimal House

Jan/Feb 2001 By Brian Schott ’93 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

Mar/Apr 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

Sept/Oct 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOne Meal at a Time

Mar/Apr 2010 By Robbin Derry ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBeyond Words

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By ROSALIE LIPFERT ’13 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryNever Can Say Goodbye

Sept/Oct 2001 By Sara Hoagland Hunter ’76