Mixed Company

In the turbulent early days of coeducation, men welcomed women at their own risk.

May/June 2004 Paul Gross ’74In the turbulent early days of coeducation, men welcomed women at their own risk.

May/June 2004 Paul Gross ’74In the turbulent early days of coeducation, men welcomed women at their own risk. BY

IN THE FALL OF 1972 THE FIRST coed class arrived in Hanover. Many male students were quick to see a benefit. My roommate, for instance, started datingand later would marry—one of our new freshmen.

Others weren't so sure. But I was oblivious to their simmering resentments until they boiled over a year later, when I was a senior. It was a winter afternoon. Walking back to my room in Russell Sage, I saw that the dorms red brick facade was barely visible beneath a blizzard of sheets, banners and placards. The look was festive. I wondered what the celebration was. As I drew closer I read the words on the sheets, the banners, the placards: "No Coeds in Sage!" "Keep Co-Hogs Out!" The face of the dorm was white with rage.

A dozen dormmates were milling around the front door. One of them of-fered me an anti-coed petition to sign. "They want to put coeds in Sage next year, even though we voted it down," he said.

I looked at him in astonishment and declined the petition.

Climbing the stairs to my single room, I found myself wishingwith all my heart that my dorm were coed. Sophomore year I had spent a semester as an exchange student at Wellesley to fill what seemed like an important gap in my social education. I liked going to college with women. I entered my room ashamed of the sentiments blaring from my dorm.

Feeling I had to do something, I grabbed a large sheet of cardboard and a black marker and sketched a circle with a plus sign underneath, the symbol for woman. I drew a crude fist inside the circle, then taped the sign to my window. Almost immediately, I heard angry voices.

"Hey, who put that sign up?" "What the...?" "Whose room is that?"

I bounded down the stairs and stepped outside. 'Are you looking for the person who put that sign up?" I volunteered. "Well, I did."

"Do you know what it's like living in a coed dorm?" someone asked sharply.

"Yes," I answered brightly. "I spent a semester at Wellesley. It was great."

Just as I thought we were going to get into a discussion about what it's like to have women as part of everyday college life, a large figure stepped forward. "Then why don't you go back to Wellesley? You're probably a faggot anyway," he said, his voice dripping with hostility.

This stopped me cold.

I knew the conventional way to retaliate: Deny the charge and fire back in kind. But things no longer seemed so simple to me. A good friend—a class-mate—had recently confided to me that he was gay and had told me about the angst of his realization. Brushing off my accuser by denying the charge and calling him a faggot would make me feel disloyal to my friend. It would be a cowardly, cheap shot, as if fending off a Nazi by proclaiming ones non-Jewishness.

I tried to come up with an alternative, but I was too stunned to think straight. In the tension of that moment, the absurdity of the accusation didn't dawn on me: A man who only wanted to live with men was calling me a homosexual because I felt differently.

After a painful silence, I eyed my accuser, gave a dumbstruck shake of the head and retreated into Sage. Back in my room, feeling flustered and alone, I heard the thwack of snowballs against my window. But I refused to budge. The sign stayed. Later that day a new pro-woman banner appeared from someone else's window at Sage. It was ripped down instantly.

Over the next few days, I worried about my room being vandalized. My stomach knotted up whenever I strolled past any group of students in the dorm. I felt like a target, an outcast.

I shared my predicament with a couple of underclassmen, gentle souls who lived on my floor. They told me they also favored a coed dorm but were afraid to say so publicly. One even signed the petition that I'd pushed aside. "Sometimes," he said, "you have to look after yourself."

I understood. At the same time, I wondered why listening and reasoning-the hallmarks of a liberal arts education-had evaporated in this vortex of hostility.

Things got worse. The student who called me a faggot now loomed every-where—in the hall, on the stairway, in the laundry room. Each time he caught sight of me, he delivered the same swaggering taunt: "There's that Wellesley faggot!" His intimidating physique intensified the effect of his bullying. I figured that if he were to take a punch at me, he could knock me senseless.

Nonetheless, I grew tired of his abuse and finally responded with a crude in- sult—"shithead," I called him—wishing it were more imaginative. In firing back, I felt I was tempting fate: Something ugly—and violent—could take place. My tormenter muttered threateningly about backing up words with action. But I didn't back down. From then on we were locked in the same excruciatingly stupid dance, "Wellesley faggot." "Shithead."

I couldn't believe that this was happening. Over the years I'd lived down the hall from many Dartmouth men whose boisterousness and fondness for beer I didn't always share, but we'd always gotten along. Now I was bumping up against a shadowy underside of a campus I thought I knew well. All because women wanted to move in next door and I'd voiced my approval.

Winter crept toward spring. Snow melted. The banners disappeared from Russell Sage, and a short while later I removed my little fist from its perch.

When I graduated on a sunny spring day, my feelings of loss were tempered by relief at leaving behind a neighbor who sneered and called me a faggot every time he saw me. As I took a last look at the Green, at Baker Library and Robinson Hall, I thought about how much had changed since that winter afternoon when I had set out to show that women belonged in Russell Sage. As I prepared to depart my college, I no longer felt that I belonged. In spite of friends, deeply etched memories and an unwavering attachment to the simple magnificence of this campus, I left wondering whether my sense of belonging would ever return.

Today I am raising two young daughters. Should they decide to visit Dartmouth as applicants, I know they won't be greeted by signs that say "Keep Co-Hogs Out!" After 30 years of coeducation, atti- tudes have changed.

It would please me if the kind of incident I experienced would be unthinkable today. I hope the Dartmouth community has become more inviting to outsiders, more curious about the unfamiliar, and that newcomers, however different, feel tolerated and embraced.

It would please me if one day, standing before Russell Sage, I could look up at the window that once bore a woman's fist and say with pride and certainty: Yes, I do belong here—and always did.

Sage Advice? This unwelcome scene greeted female students in winter 1974. It was the second year of coeducation.

PAUL GROSS is a physician who lives in NewRochelle, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

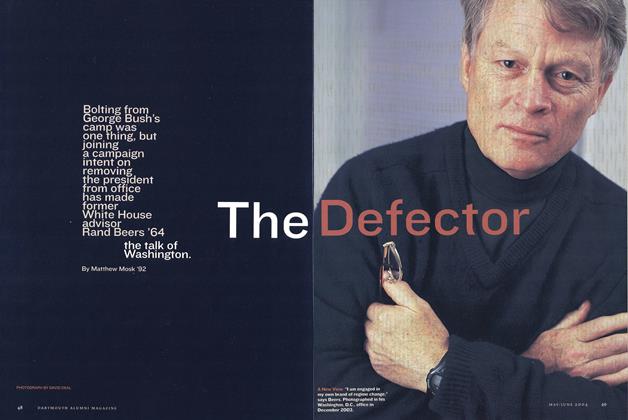

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

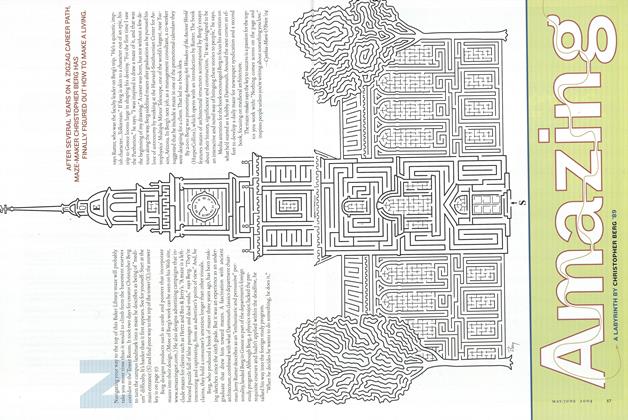

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYAristotle on the A-Train

Nov/Dec 2007 By Alexander Nazaryan ’02 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

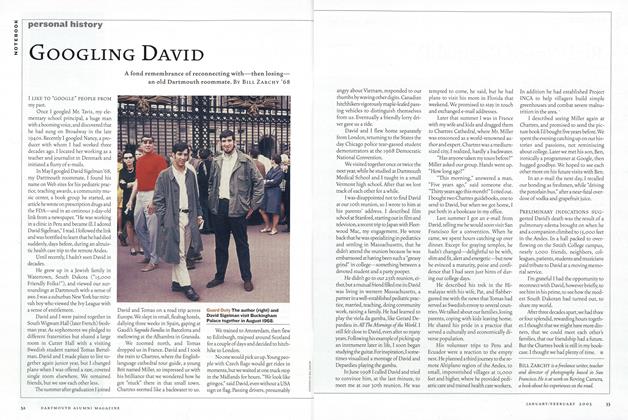

PERSONAL HISTORYGoogling David

Jan/Feb 2005 By Bill Zarchy ’68 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

Sept/Oct 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May/June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBuddha on the Water

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By JEREMY HOWICK ’92 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66