What is Perfect?

A former Rhodes Scholar reexamines the value of intelligence with a little help from her 5-year-old.

Sept/Oct 2000 Mary Cleary Kiely ’79A former Rhodes Scholar reexamines the value of intelligence with a little help from her 5-year-old.

Sept/Oct 2000 Mary Cleary Kiely ’79A former Rhodes Scholar reexamines the value of intelligence with a little help from her 5-year-old.

ON THE BRIGHT JUNE DAY THAT MY husband, Chris, and I were to drive to Hanover for my 15 th reunion, the phone rang in our home in suburban New Jersey. It was our obstetrician. I was four months pregnant with our second child. The doctor was tense. "Your alpha-fetoprotein (a prenatal blood screening) came back low," she said evenly. "This means the baby has a higher than average risk of Down syndrome—a lin 70 chance in your case. Do you want to find out for sure with an amniocentesis?" "We'll get back to you," I said. I hung up the phone and burst into tears.

Five years later, that child is with us and running around. We named her Christina Marie, and she did indeed come to us with Down syndrome. The genetic anomaly occurs once in every 800 to 1,000 live births and results in a characteristic physical appearance and various degrees of cognitive impairment.

These days I don't cry about Christinas condition, but neither am I glib. While all parenting entails tremendous vulnerability, parenting a child with special needs sometimes involves losses and difficulties and worries that are different or more intense. For example, there are the issues of how our daughter will get on in a world increasingly obsessed with perfection, and what it will mean for both our girls when my husband and I are no longer alive. But most of the time we try to focus on the present and enjoy it as much as possible, for more and more we have come to appreciate that while life with Christina is probably never going to be easy, it is very good. Unlikely as this prospect seemed in the dark days after her birth, this little girl has turned out to be one of the most powerful teachers in my life.

The early days were indeed dark. When Chris and I opted for me not to have an amniocentesis, it was mostly because we had decided we would have the baby, Down syndrome or not. We just didn't think we were wise enough, could ever be wise enough, to decide in advance whether our child's life would be worth living. The advantages of knowing whether our child would be affected were outweighed, we felt, by the possibility that we would have to go through the rest of the pregnancy awash in fearful speculation. But at the same time we also believed (or at least were hoping madly) that it would never happen to us. The odds, after all, were still very much in favor of a healthy child. So when Christina, at 8 days old, was finally diagnosed via chromosome analysis, I felt strangely unprepared. I felt like a latter day, extremely bad-tempered Dorothy in Oz, railing at the heavens and shouting, "Excuse cuse me! Wrong stop! I just realized I can't handle this!"

"This," as we soon found out, was in part a dizzying and often exhausting foray into the world of children who are ill or have special needs, a world we had never given much thought to before. Christina turned out to have heart, vision and thyroid problems, along with a chronic immune deficiency that makes her very prone to respiratory infections, so we began spending a lot of time dealing with medical issues. To help Christina compensate for the cognitive deficits and motor delays that usually accompany Down syndrome, we also, from the time she was 2 months old, began working with physical therapists and special educators, and later with speech and occupational therapists. It was no wonder that when Chris's career led us to move to France when Christina was 10 months old, it felt like our second foreign country in a year.

In many ways, however, the most challenging aspect of having a child with Down syndrome has been grappling with the issue that was recently and quite aptly raised by our 6-year-old daughter, Bridget. "Mommy," she said to me one afternoon, "it's okay to have Down syndrome, right?" "Yes," I replied, "why do you ask?" "Well," she went on, "you said a few days ago that Christina has Down syndrome because of a mistake that happened when she was in your tummy. Does that mean Christina is a mistake?" Good question. To which an alarming number of people today apparently would answer yes.

It is an important step to move from acknowledging the existence of conditions that render people weaker in some respects to concluding that the individuals so affected should be weeded out. And yet, many seem to believe that coming to such a conclusion is inevitable. Professor Peter Singer of Princeton, a former president of the International Association of Bioethics, supports the infanticide of disabled infants, including those with Down syndrome, arguing that parents, by getting rid of such babies, still may have the opportunity to have "another pregnancy, which has a good chance of being normal." Closer to home, a Dartmouth classmate, who I feel quite sure would find the idea of infanticide abhorrent, nonetheless was obviously shocked that we had allowed our child to come into the world. "I had amnios with both of my pregnancies," she said (I think more to herself than to me), "and I was prepared to take action if necessary!" She is not alone. According to CBS News, the abortion rate in the United States today for fetuses found to have Down syndrome is approximately 97 percent.

One might imagine that the children so many want to "take action" against are monsters. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our daughter, who recently turned 5, is a delight. We should all be so lucky as to have a child about whom the nursery school teachers main complaint is that she can't resist dancing on the tables during music! Or a child whose courage and persistence in the face of frequent illness and ever-present physical and mental challenges set a standard for those of us who often whine over lesser difficulties. Or a child who can make even the gruffest of strangers break into the kindest of smiles, just because she isn't afraid to reach out with a handshake or a grin. So okay, it took Christina a long time to learn to walk, much less to dance, and her speech is still difficult for most people to understand. But in terms of heart and spirit, she soars. Living with this little girl and her gifts of joyfulness and gentleness ciate how undervalued such qualities are in our society and how much we have need of them.

These days I think back with some embarrassment to a time not so long ago when I believed that IQ was a pretty good predictor of one's chances for a happy and productive life. Valuing intellectual accomplishment—almost above all else—led me first to Dartmouth and later to a Rhodes Scholarship and a teaching career. But now I have a greater sense for how much life resists the little formulas that we would squeeze it into. While the pleasures and the powers of intelligence can be considerable, intelligence possessed is not necessarily intelligence used. And intelligence without heart can be a very dangerous thing—a lesson that we need to be reminded of over and over again. I watch my daughter, who cannot stand to see someone else in distress. She invariably rushes over, lips trembling or eyes filling, to comfort the other with a pat or a hug. Then I read about kids shooting other kids, and I wonder: Whose deficiencies are the more serious? Those of children like my daughter, or those of children like the shooters, who presumably came into this world labeled normal?

The bottom line is that we are all both gifted and blighted. Physical and mental weaknesses are just more immediately obvious, quite often, than moral or spiritual ones. We can put all the faith we want in medical technology and its predictive or corrective pow- ers. But perfection will forever remain an imaginary construct. It is not an objective or achievable reality, much less (as our generation sometimes seems to regard it) an entitlement. As I have learned from the little child who has turned out to be the vox clamantis in deserto of my life, we do not love those we love because they are perfect. Rather, they are perfect because they are loved.

"Intelligence without heart can be a very dangerous thing—a lesson that we need to be reminded of over and over again."

MARY CLEARY KLELYlives with her husband and two daughters in Paris. She wasDartmouth's first female Rhodes Scholar.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

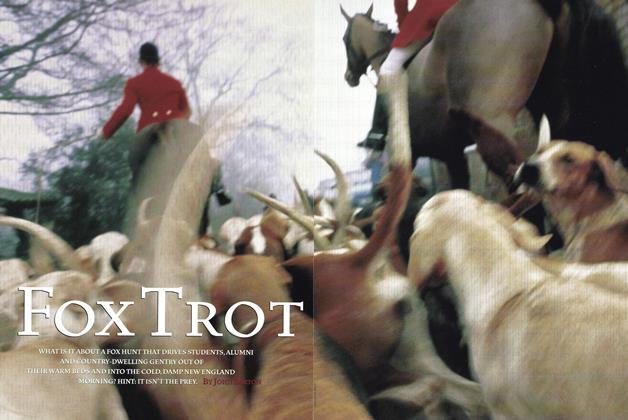

FeatureFox Trot

September | October 2000 By John Barton -

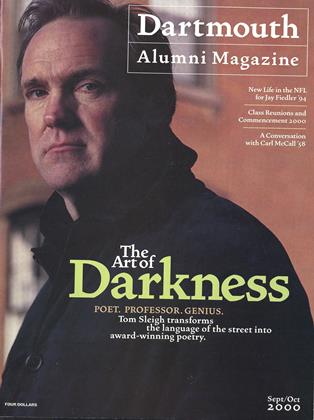

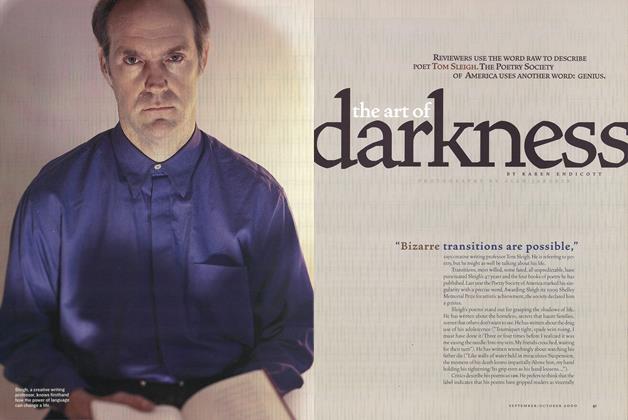

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

September | October 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

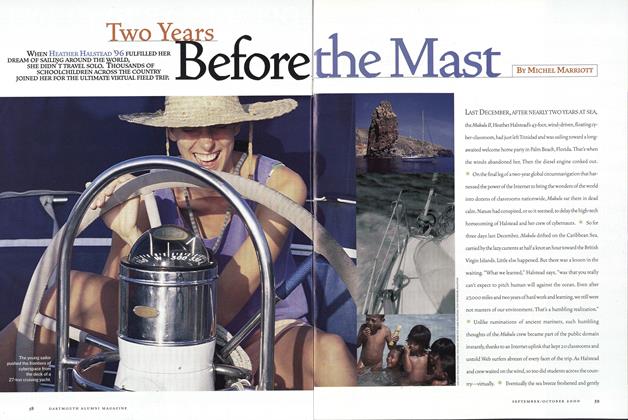

FeatureTwo Years Before The Mast

September | October 2000 By Michel Marriott -

Feature

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

September | October 2000 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

September | October 2000 By Brad Parks '96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

September | October 2000 By Karen Endicott

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHappy Feet

May/June 2010 By Anne Jakle ’03 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGoogling David

Jan/Feb 2005 By Bill Zarchy ’68 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGoing to the Mat

Sept/Oct 2010 By Diana (Sabot) Whitney ’95 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryGreen Jacket Abroad

Mar/Apr 2004 By Laurence Sterne ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBreakaway

MAY | JUNE By SAM HULL ’56 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May/June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79