WHEN THE EDITORS OF DAM ASKED me to contextualize Peter Jaquith's story, I welcomed the opportunity. In the 28 years I have been treating people addicted and recovering from alcohol and drug problems, I have never tired of stories of miraculous transformation. Each of these stories is as unique as the person telling it, but within these inspirational stories certain themes consistently emerge. While in the throes of addiction, for those who are gifted, well- educated and successful, the most common experiential denominator is: This can't happen to me!

How could a person who reached the pinnacle of success have fallen to the low- est rungs of society without redirecting his will and behavior? How could he have squandered his career, family, friendships and personal values without any observable signs of regret or resolve? Earlier in his life, during his Dartmouth and Wall Street days, how could he have ignored the numerous red flags? And lastly, how could a man who obviously had people who loved and cared about him fail to obtain effective professional help at some point along the way?

Jaquith describes the course and out-come of "an incurable and terminal disease. " As documented with anecdotal evidence in the past, technology now provides concrete evidence for our innate tolerance or resistance to substances, as well as the cumulative brain changes that occur with exposure to substances such as alcohol, cocaine and heroin. Once the brain becomes addicted, these changes functionally affect the pursuit (and valuation) of rewards, and cognitive processes such as memory, judgment and insight—why many describe addiction and alcoholism as "the only disease that tells you that you don't have it."

Although not every time Jaquith drinks alcohol something bad happens, every time something bad happens he has been drinking—beginning with his Dartmouth days. This experience often serves as a superficial denial of a problem. Meanwhile, an undertow of poor academic performance, arrests and accidents is slowly swelling below the surface of his consciousness.

During graduate school and his early careerJaquith's problem festers unchecked and insulated by image, isolation and income. His rising-star status protects him from the usual stereotype of one with a drinking or drug problem. The autonomy that a high-status professional enjoys enables drinking or drug use without detection. He can afford substance use at costs that would bankrupt a middle- or lowerclass person. Each of these dubious benefits of success permits the disease of addiction to flourish.

As life progresses, the relationship with alcohol or drugs becomes primary. In perverse fidelity to this primary relationship, the high-achieving professional will slowly squander everything and everyone else. First to go are recreational activities, next are social and family relationships and, finally, physical health. The high-powered profes sional will usually protect this facade at all costs. Some have even preferred death to discovery, fearing shame and humiliation.

If an addicted person survives this phase, the severity of the problem can no longer be concealed and the pretense becomes impossible to maintain. Usually after some type of crisis or intervention, there maybe a leveraged treatment experience, for example residential detoxification at a hospital or even at a rehabilitation program. As with other types of health care, the quality of these treatments varies considerably. Often the person and his or her loved ones confuse simply not drink- ing or not using the substance as the "cure" for the disease. There also may be efforts to drink or use in moderation, or to "trade up" from hard drugs to alcohol or marijuana, or even from hard liquor to beer or wine. These bargains prove costly.

Research has demonstrated that treatment for alcohol and drug problems is as effective as treatments for other chronic diseases such as diabetes and asthma. Addiction must be accepted as chronic, and it requires ongoing routine medical monitoring and substantial life changes to pre vent relapse. No silver bullet exists. Effective treatment helps an addicted person maintain abstinence and facilitates positive lifestyle changes. Mutual self-help groups understand addiction as a physical, mental and spiritual disease, and offer supportive fellowship to address these aspects.

In the almost 50 years since Jaquith was at Dartmouth there has been great progress. The College offers prevention programs to incoming students to evaluate their own personal risk of developing a substance-use problem. The deans' offices and the Colleges health service offer voluntary and mandated early intervention for students who demonstrate early warning signs of alcoholism. The Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center has a treatment program for persons who have alcohol or drug-dependence diseases. Under the auspices of the Dartmouth Center on Addiction, Recovery and Education, a fellowship of Dartmouth men and women who have experienced at least two of the "Ds" that Jaquith refers to have formed a network called the Alumni Forum for Recovery at Dartmouth (www.dartmouth.edu/~dcare). This is an innovative venue for Dartmouth alumni in recovery and those still suf- fering addiction and seeking mutual sup- port and compassionate information if not help.

Jaquith suffers from an incurable disease. He reports being well today. There is no absolute guarantee for his future. If he continues to respect the chronicity and the depths of all aspects of his illness, his prognosis is excellent. In recovery, telling ones story is an important part of humility and of service to others who may benefit from the teller's experience, strength and hope. To the degree he tells his story with this in mind, Jaquith will certainly know a new freedom and a new happiness.

MARK MCGOVERN is an associate professor ofpsychiatry at Dartmouth MedicalSchool. He is theco-author of the forth coming This Can't Happen to Me: The Addiction and Recovery of Highachieving Professionals (W.W.NortonPress).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

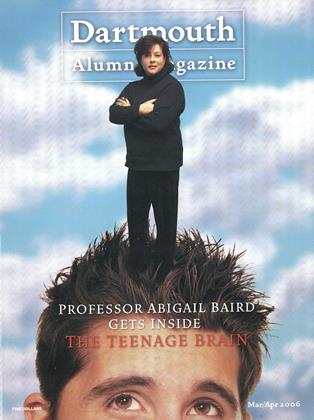

Feature“D” is for Denial

March | April 2006 By PETER JAQUITH ’58 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

March | April 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2006 By Paul Stone '60 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Stages of Life

March | April 2006 By Nell Shanahan ’99 -

Sports

SportsThree Times a Coach

March | April 2006 By Brad Parks ’96

Article

-

Article

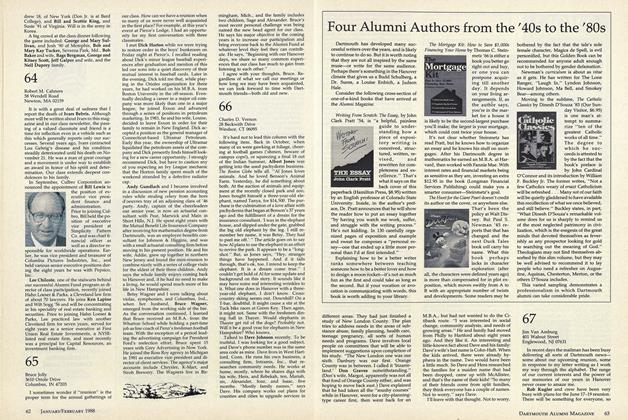

ArticleJUNIOR PROM COMMITTEE

-

Article

ArticleFour Alumni Authors from the '40s to the '80s

FEBRUARY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleWestchester

MARCH 1971 By J. Richard Prior '60 -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

May/June 2004 By Robert Perron '59 -

Article

ArticleSomething Novel in Fires

DECEMBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32