The Slaves of Dartmouth

Slaves built the White House and the Capitol in Washington, D.C. They built Trinity Church in New York. They probably helped build Dartmouth Hall.

Jan/Feb 2007 JAMES ZUG ’91Slaves built the White House and the Capitol in Washington, D.C. They built Trinity Church in New York. They probably helped build Dartmouth Hall.

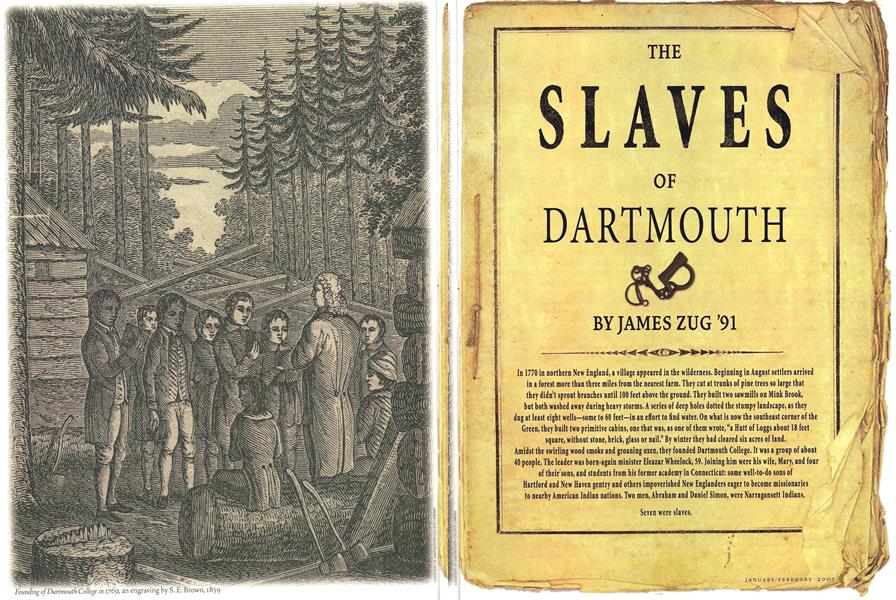

Jan/Feb 2007 JAMES ZUG ’91In 1770 in northern New England, t village appeared in the wilderness. Beginning in August settlers arrivedin a forest more than three miles from the nearest farm. They cut at trunks of pine trees so large thatthey didn't sprout branches until 100 feet above the ground. They built two sawmills on Mink Brook,but both washed away during heavy storms. A series of deep holes dotted the stumpy landscape, as theydog at least eight wells—some to 60 feet—in an effort to find water. On what is now the southeast corner of theGreen, they boilt two primitive cabins, one that was, as one of them wrote, "a Hutt of Loggs about 18 feetsquare, without stone, brick, glass or nail." By winter they had cleared six acres of land.

MOST OF US TEND TO THINK IN BIFURCATED terms about slavery. We imagine that the North—especially pious New England—has an unsullied history of freedom, innocence and abolitionism, and that slavery was a benighted Southern vice. The truth is much more complicated.

New England was a slave society. The first African slaves arrived in New England in 1638. A slave testified at the Salem witch trials. When John Campbell published New England's first newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, in 1704, he ran ads from slave merchants. Benjamin Franklins brother sold slaves at his Boston tavern.

When Wheelock founded Dartmouth, slavery was at its height in New England. More than 16,000 people in the five New England colonies (about 3 percent of the total population) lived in chattel bondage. That spring Crispus Attucks, a former slave who had fled his Framingham, Massachusetts, master 20 years earlier and remained free, was the first to die in the Boston Massacre. Slavery was an integral thread in the regions fabric. Merchants in Newport, New and Boston dominated the lucrative international slave trade. Slaves toiled in spermaceti factories, on whalers, in shipyards and as house servants. Nearly three-fourths of Bostons upper class owned a slave, as did half of Connecticut's ministers. Slavery was so prevalent that even New England's Quakers owned slaves, and some local Friends meetings were unable to follow a London-mandated rule that any Quaker slave owner had to be disowned.

Slaves in New England lived under conditions similar to those on indigo and rice plantations in the South. The violence of chattel bondage—manacles, abuse, rape, whipping, mutilation, branding, even death—occurred in New England as in South Carolina. Manumission was rare, and the few free New England blacks lived under a welter of restrictive laws.

Nonetheless, slaves carved out a tenuous niche in New England. Because most Northern households, unlike Southern plantations, kept only a few people at a time, slaves could often blend into the general society in the same class as indentured servants, poor whites and Native-American wage workers. They learned crafts, especially in the maritime trades. (Attucks, for example, was a sailor.) Although considered property themselves, they could own property. They grew food that they sold. If they were lucky, they married and had children and, in very rare cases, knew their grandchildren.

They also had fun, if just once a year. Slaves and free blacks in most New England cities hosted their own annual black Election Day—often coinciding with the white voting day—in which they paraded through town in outrageous costumes, danced, feasted and sang. During these Mardi Gras-like festivities they elected their own so-called governors and kings, who unofficially represented their communities. Dripping with irony, Election Day was a raucous reminder to white New England that slaves were humans too.

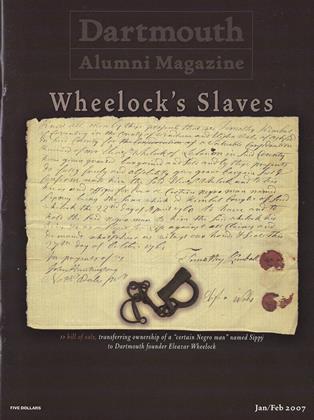

WHEELOCK WAS A LONGTIME SLAVE OWNER. In 1743 he paid £245 ($58,000 in 2006 money) for a 22-year-old named Fortune. Later he bought Dinah, Ishmael ("being a servant for life," according to the bill of sale, which is part of Rauner Special Collections), Sippy ("a certain negro man") and Peggy, whom he soon gave to his daughter Mary. Wheelock, unlike many slave owners, did not think Africans were beyond redemption. An evangelical Congregational minister, he converted numerous slaves to Christianity and once proudly reported that he brought a service in Boston to such a feverish pitch of emotion that, "Col. Leonard s negro [was] in such distress that it took 3 men to hold him. I was forced to break off my sermon before I had done, the outcry was so great."

When Wheelock left Connecticut for Hanover in 1770, he brought along at least seven of his slaves: Brister, Exeter, Chloe, Caesar, Lavinia, Archelaus and Peggy.

This was not their first journey as slaves. They were Bambara or Ibo or Mbundu. They most likely had been born in the interior of West Africa (some slaves had been born in New England; even fewer were born in the West Indies). They had been captured in a war or kidnapped. Dragged to the coast, they were sold to slavers, who chained and crammed them into dank, suffocatingly hot holds. They sailed across the Atlantic—the epic terror of the Middle Passageand landed perhaps in the West Indies or in North America. There they were poked and prodded at a slave market and sold.

Wheelock had bought Brister in April 1760 from Peter Spencer of East Haddam, Connecticut, for £65 (about $15,500). Brister was 21 at the time and, as Spencer wrote, "is of a healthy and sound constitution and is free from any distemper or disorder of body or mind that may prejudice his usefulness in the capacity of a slave.

Two years later Wheelock bought three more slaves: Exeter, 47, Chloe, 35, and the couple's 3-year-old son, Hercules. Exeter was known as the "Spotted African," for he had several inch-wide copper-colored marks on his face. He also had a notorious temper, which might have prompted Wheelock to try to sell him three years later. Wheelock offered Exeter, Chloe and their 2-year-old unnamed daughter. (He was keeping Hercules, whom he was educating and planned to free at age 28.) "Said Exeter," Wheelock wrote, "is a well healthy man and as good a man for business, will do as much as any man I ever employed, and understands all parts of husbandry work well, has a fine resolution, and is as great a stranger to weariness as ever I saw, and I had rather have him in my business than any of his colour I ever knew; excepting on account of the violence of natural temper. He is honest, manly, kind, neighbourly when out of his passions. And is a fellow of truth so far as ever I have discovered excepting when in his passions, and at such times he will lie, and sometimes swear."

Apparently, there were no buyers, and Exeter, Chloe and their children continued to live with Wheelock. They prospered enough to own a cow, which Wheelock did not allow them to bring to Hanover, since it would cost at least 40 shillings to pay for feed over the winter. Exeter protested, but to no avail.

DARTMOUTH WAS BASED ON THE IDEALS OF the Enlightenment. It was supposed to be a place to "encourage the laudable & charitable design of spreading Christian Knowledge," as the College charter stated.

For Wheelocks slaves it was a prison. They endured the cold Hanover winter—no doubt without the warmest of clothingwhile probably living, like some of the students, in tents behind Wheelocks cabin. They probably wished they were still in Connecticut. There the weather was not so harsh and it was more social, with travelers passing through, visiting with neighboring slaves and Hartford's infamous Election Day party. In Hanover they were all alone. Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the nearest town with a sizable black population, was three days' travel away.

It could have been the climate or isolation or Wheelock s treatment, but for some reason Exeter's bad temper reared its ugly head again. The sheriff in Lebanon, New Hampshire, charged him with "grate abuses to your wife Cloe and you let your bad temper rage." His punishment was unknown.

Another slave who ran afoul of the law in Hanover was Caesar. He was the cook at the College and named, as were so many other 18th-century slaves, after a great historical figure as a kind of patronizing joke. (Slave owners rarely gave surnames.) In the winter of 1773 Wheelock had Caesar arrested for slandering a white woman, Mary Sleeper, who lived in the Wheelock household. Caesar had been overheard gossiping that both Brister and Archelaus "have had carnal knowledge of her the said Mary, and that she was fond of it." On February 8 Caesar was found guilty, fined 10 shillings and ordered to place £10 as a deposit by sunset or be flogged seven times on his naked back.

The case revealed a lot about slavery at Dartmouth. It brought up the explosive issue of miscegenation, which would lead to so many lynchings throughout America. It showed the limits of Wheelock's power. As with Exeter and his bad temper, Wheelock had resorted to the courts instead of simply whipping Caesar. Most of all, it exposed the widespread support the Dartmouth slaves had in Hanover. Before the end of the day, 31 Dartmouth students (about half the student body, including John Ledyard, class of 1776) and one Hanover shopkeeper signed a letter saying that they themselves would give £lO to Wheelock if Caesar was not "of good behavior & Conduct" in the future.

Regardless—or because—of the students' opinion, Wheelock sold Caesar to a Captain Moses Little for £20 (about $4,750 today) three months later.

SLAVES BUILT THE WHITE HOUSE AND THE Capitol in Washington, D.C.TheybuiltTrinity Church in New York. They probably helped build Dartmouth Hall.

Wheelocks slaves were not the only able-bodied workers on the campus. Most students, including all the "charity" students who did not pay tuition, labored on College projects. Wheelock also hired local farmers. But no doubt his slaves lent their muscle to various tasks on campus: the clearing of acreage, sowing of grain, fencing of pasture, care of cattle and erection of the College malt house, wash house, bake house and barn. Dartmouth Hall was started in 1784 and completed in 1791. Until it burned in February 1904, this great building at one time or another was the home of classrooms, dorm rooms and the College library, medical school and chapel. It probably contained, frozen in its wooden amber, the sweat of slaves.

By the time Wheelock died in April 1779, he had not emancipated all of his slaves. Just before he passed away, he freed Exeter and Chloe; they died in Hanover in 1783. (Their gravesites are unknown; many unmarked graves exist in the College cemetery.) In his will he gave Brister, Archelaus and Anna, a new slave, to his son John, the second president of the College. The elder Wheelock specifically manumitted Archelaus, still not of age, when the slave reached his 25th birthday, "provided his moral character, his ability to conduct himself among men and provide for his own subsistence shall be judged by the Revd. Grafton Presbytery to be such as that he may safely be trusted with his freedom."

For Brister, who had been with Wheelock for nearly 20 years, Wheelock devised another contingent plan. Brister was to receive his freedom and 100 acres of land if he could secure a wife. Six months after Wheelocks death, Brister wrote to Selinda Welch, a slave in Connecticut owned by a Mr. Bingham, asking if she would many him. Bingham asked Brister to come to Connecticut to negotiate for the manumission of Welch. The deal apparently fell apart and no marriage took place. Brister died alone in Hanover in 1805 at the age of 70.

BRISTER MIGHT HAVE STILL BEEN A SLAVE at his death, for slavery did not end in New England with the American Revolution.

Vermont became the first colony to ban slavery, with its 1777 constitution, although it did not become a state until 1791 (the 1790 federal census counted 16 Vermont blacks who were probably slaves). The Rhode Island and Connecticut state assemblies, after considerable delay and discussion, passed gradual emancipation laws. In 1781 and 1783 Massachusetts' highest court ruled that slavery was illegal.

New Hampshire had a murky end to chattel bondage. The legislature did not pass any abolition laws, and until 1789 slaves were counted as property for tax purposes. Instead, slavery was left to wither under the weight of public opinion.

That opinion was decidedly mixed. In 1788 a justice on the New Hampshire Supreme Judicial Court declared that slavery was still legal. The 1790 census counted 157 slaves in New Hampshire, and throughout the early 19th century slaves lived in the Granite State: Three slaves were listed in the 1830 census. Even the supposed end of New Hampshire slavery—in 1857 the state legislature passed a law saying that "no person, because of descent, should be disqualified from becoming a citizen of the state"—did not specifically outlaw slavery. "If you want to be strict about it," says James O. Horton, a professor at George Washington University and a leading expert on 19th-century African Americans in the North, "it was the 13th Amendment that really abolished slavery in New Hampshire, when the state ratified it on July 1,1865."

Beyond New Hampshire, New England was slow to fully eliminate slavery. Slaves were included in the population categories for New England states until the 1850 federal census. Rhode Island did not completely abolish slavery until 1843, Connecticut until 1848. Complicity with Southern slavery was another issue: Many New Englanders built financial empires based on slavery—cotton mills, rum distilleries, even selling cod to West Indian planters. Nathan Lord, president of Dartmouth from 1828 to 1863, held strongly proslavery views and published an open letter to Dartmouth undergraduates in 1859 arguing for a biblical justification of slavery.

Lord probably knew former slaves in Hanover. Traces of slavery were apparent in Hanover after Eleazar Wheelock's death. A1786 census recorded four slaves in Hanover. More than 2 o blacks, some of them possibly slaves, lived and died in Hanover in the 19th century. One memorable townsman was Lundon Dow. He had been born in Africa and had lived as a slave in Connecticut. Dow died in 1819 at age 100.

DARTMOUTH IS NOT THE ONLY COLLEGE with slavery in its attic. Every pre-Revolution university has direct connections to slavery—and some have begun to examine their histories. Their experiences provide good examples of how Dartmouth might—or might not—proceed.

In April 2004, after a law professor named Alfred Brophy marshaled evidence, the faculty at the University of Alabama (founded in 1831) apologized to the descendants of slaves who were owned by faculty members or who worked on the campus before the Civil War. The university also put a marker at the campus grave of two slaves and appointed a vice president for diversity.

Emory University (founded in 1836) began examining its own history after a September 2003 anthropology department panel discussion in which a white professor uttered the phrase "six niggers in a woodpile." Emory launched the Transforming Community Project (TCP). Aimed at researching Emory's past, developing curriculum and encouraging community dialogue and reflection about race, the TCP is a massive project, slated to last five years, with a full-time director and a Ford Foundation grant. "It is less a sense of discovery," says Leslie M. Harris, a history and African-American studies professor and co-chair of the TCP, "since in Georgia there is quite an awareness that slavery existed, but more a sense of a discovery of connections to today, such as, what is the meaning of this today?"

While a racial incident catalyzed Emory's investigations, at Yale University it was almost the opposite. During Yale's tercentenary celebrations in 2001 three Ph.D. students (in history, psychology and philosophy) read a Yale-produced pamphlet that trumpeted Yale's role in the abolition of slavery. In response, they researched and wrote a pamphlet and launched a Web site minutely detailing Yale's extensive involvement with slavery. The scholarship was not brilliant, but it was shocking. Eight of the 12 Yale residential colleges were named after slave owners, and money from the slave trade financed Yale's first endowed professorship, its first endowed scholarships and its first endowed library fund.

The students published their pamphlet in August 2001. TheNew York Times reported on it immediately, running long articles, editorials and letters to the editor. Richard Levin, Yale's president, was on holiday in the Swiss Alps, and the administration scrambled to manage what was becoming a public relations nightmare. (Its first statement to the Times was, basically, "Everyone did it back then.") But September 11 came, and everyone's attention shifted.

Yale did put up a plaque inside the entrance to Dwight Hall, Yale's social service headquarters: "Dwight Hall at Yale renounces the pro-slavery thought and actions of Timothy Dwight, while reaffirming our predecessors' work on behalf of justice and equality." (Timothy Dwight had owned one slave and had been a supporter of slavery while president of Yale.) The university did not put up a plaque on Calhoun College, however, which was named after John Calhoun, a slave owner and leading slavery advocate in the U.S. Senate. What might have happened at other universities—the president creating a center to systematically research and discuss slavery—was not a consideration, because Yale already had such a center, the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition, founded in 1998 and still the only such institution in North America. The center supports post-doctoral researchers, holds conferences and runs a lecture series. Along with the Yale Law School it hosted a conference, "Yale, New Haven and American Slavery," in September 2002.

"The Gilder Lehrman Center took the wind out of the sails before it got too far," says Robert P. Forbes, an associate director at the center. "But the issue still remains. What we are finding is that we are moving from a flashlight phenomenon, where we illuminate small pockets of a dark landscape, to beginning to light up the whole room. It is potentially traumatic, but we are in a paradigm shift toward understanding slavery as a global issue, where Yale, New Haven and Connecticut were a leading edge of the western wing."

The most publicly sustained discussion has occurred at Brown University. In April 2003 Ruth Simmons, the president of Brown and a great-granddaughter of slaves, set up a steering committee to examine Browns connection to slavery. The committee uncovered material about the Brown family, which helped found the university (the Browns not only owned slaves and used them to build the university, they even sent ships to Africa to bring back slaves); placed a voluminous amount of material on Brown's official Web site; helped launch a history class at Brown; wrote a unit, "A Forgotten History: The Slave Trade and Slavery in New England," for the popular Choices high school curriculum series; created an exhibit for the Rhode Island Historical Society about the Sally, one of the Brown family's slaving ships; and brought nearly 100 speakers to campus to participate in more than 30 public lectures, panel discussions, workshops and international conferences, (it also co-sponsored a conference at Yale's Gilder Lehrman Center in October 2005, "Repairing the Past: Confronting the Legacies of Slavery, Genocide & Caste.")

Brown delivered its final report in October 2006 (it can be viewed online at brown.edu/slaveryjustice). "We want to be a model for other universities on how to facilitate serious and sincere discussion of complicated issues," says James T. Campbell, a history professor at Brown and chair of the school's steering committee on slavery. More discussions are planned for in 2007, to coincide with the bicentennial of the abolition of the British Empires slave trade in March 1807. Murmurs of activity have been heard at Southern universities such as Ole Miss, UT Austin, Virginia and South Carolina. The University of North Carolina has just finished displaying a major library exhibit about the history of slavery and UNC.

"Universities are ideally positioned for this sort of dialogue to occur," says Campbell. "They have unique intellectual resources, and such truth-seeking is at the heart of their missions. Universities already care deeply about their own past, so it is in their nature to examine it more closely. And universities can convene a searching and substantial discussion that doesn't get short-circuited by such inflammatory phrases as 'monetary reparations,' which can generate more heat than light."

WHAT COULD DARTMOUTH DO? WITH A historian as president, it could launch a campus-wide conversation about the history of slavery and the College. Montgomery Fellows could give talks. Seniors under the Presidential Scholars program could delve into the archives.

"Dartmouth is mature enough to do this. It could trust itself," says J. Martin Favor, chair of the Colleges African and African-American studies department, who is writing a book about how slavery is commemorated today in Africa and America. But it could get uncomfortable. "We are selective about what we choose to claim and disclaim from the historical past," adds Favor. "We buy into some stories and opt out of other stories. We want history to tell us good stories about ourselves. The reality of the past isn't so clean. Slavery is foundational to any 18th-century institution. We are all enmeshed. We cannot not be enmeshed. But it is very possible for Dartmouth to take this on in a positive way. There could be collaborative research and campus-wide discussion both specific to Dartmouth and more broadbased. It's worth investigating. I can see it as a miniaturized form of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. We can't change the past but we can change our relationship to it. Why can't we talk about it? This is why the College exists. We are not simply a degree-granting factory."

While undergraduates and faculty might be interested in a discussion, many alumni may be hesitant to examine this aspect of Dartmouth's history. When the alumni magazines of Yale and Brown ran articles similar to this one, they subsequently printed a number of strongly worded—if sometimes heavily sarcastic—letters from disgruntled alums accusing their alma maters of kowtowing to political correctness. Most Americans do not descend from slave owners, and it is tricky to apply current moral standards to a vastly different era.

The administration also might be wary because of the issue of reparations. The concept has been around (continued on page 100) since before the Emancipation Proclamation but was kick-started in 2000 by Randall Robinsons bestseller, The Debt: WhatAmerica Owes to Blacks. Robinson argued that the U.S. government should not only apologize to descendants of slaves but also pay monetary reparations. (One model is the federal governments 1988 apology to Japanese- Americans interned during World War 11, which included a cash payment of $20,000 to each of the 60,000 survivors.) Reparations in the 21st century mean many things: city ordinances that require businesses to research their past and disclose ties to slavery; companies setting up scholarship funds because of past connections; and even the U.S. Senate apologizing in 2005 for its predecessors not passing anti-lynching legislation. It is almost the new "Celebrate Diversity" movement, a nationwide frame for a debate about race and class in American institutions.

Colleges took particular notice of reparations in 2002, when Brown, Yale and Harvard were mentioned as likely future defendants in a class-action lawsuit brought against three corporations (CSX, Aetna and Fleetßoston) whose predecessor companies had profited from slavery. But in January 2004 the idea of pursuing monetary reparations through the courts suffered a decisive and perhaps permanent setback when a federal judge in Chicago dismissed the landmark case.

"When we started in 2003 there were two fears," says Campbell, chair of Browns slavery committee. "Universities worried about getting sued. But no university has ever been named in a suit, and since the Chicago decision it is extremely unlikely. The other issue is alumni, and there has been quite a lot of comment within the Brown alumni community. Brown is, I think, stronger now for having gone through this. Alumni giving is up, alumni participation is up, our capital campaign has gone very well. Brown has come out much better on the other end of this process."

Perhaps it is now time to turn back to the summer of 1770 and talk about Brister and Caesar and Exeter, the slaves of Dartmouth.

"WE CAN'T CHANGE THE PAST WHY CAN'T WE TALK ABOUT IT? WE ARE NOT SIMPLY BUT WE CAN CHANGE OUR RELATIONSHIP TO IT. THIS IS WHY THE COLLEGE EXISTS. A DEGREE-GRANTING FACTORY."PROFESSOR}. MARTIN FAVOR

SLAVES BUILT THE WHITETHEY BUILT TRINITY CHURCH THEY PROBABLY HOUSE AND THE CAPITOL IN WASHINGTON, D.C. IN NEW YORK. HELPED BUILD DARTMOUTH HALL.

JAMES ZUG is the author of American Traveler: The Life & Adventures of John Ledyard He lives in Washington, D.C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Right Went Wrong

January | February 2007 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Feature

FeaturePicking Up the Pieces

January | February 2007 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2007 By William Landmesser '74 -

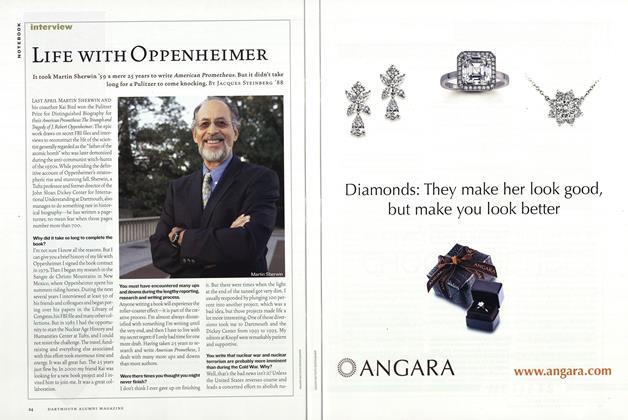

Interview

InterviewLife with Oppenheimer

January | February 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAre You a Chubber?

January | February 2007 By Lisa Densmore ’83

JAMES ZUG ’91

-

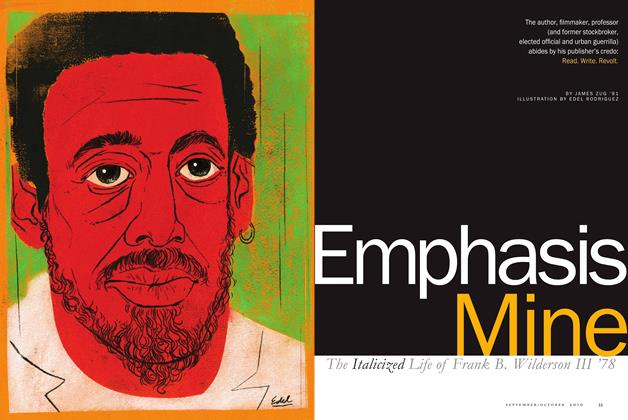

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Italicized Life of Frank B. Wilderson III ’78

Sept/Oct 2010 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

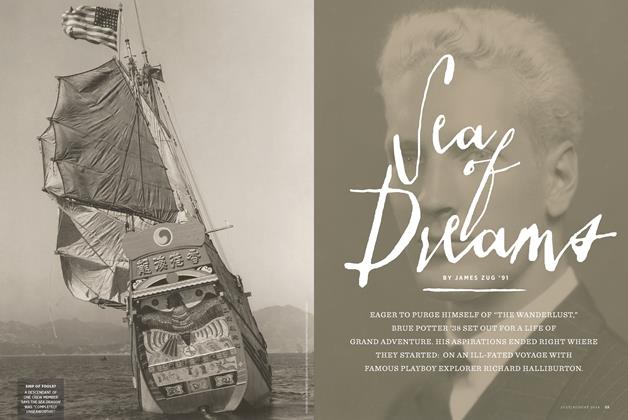

FeatureSea of Dreams

July | August 2014 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Article

ArticlePress On

MARCH | APRIL By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYKing of the Hill

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

pursuits

pursuitsPuzzle Master

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By James Zug ’91 -

notebook

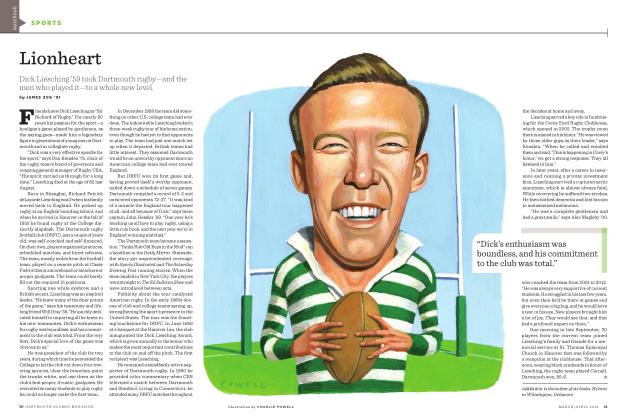

notebookLionheart

MARCH|APRIL 2019 By JAMES ZUG ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAnd More

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GOALS of a Business Society

June 1958 By ALBERT NICKERSON -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

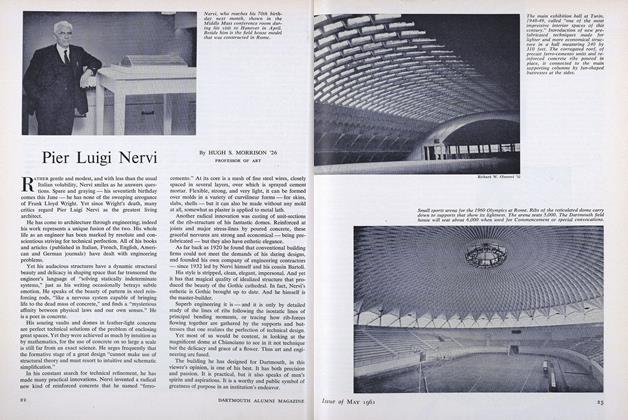

FeaturePier Luigi Nervi

May 1961 By HUGH S. MORRISON '26 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2012 By JOHN SHERMAN