Curtain Call

An architectual era ends with the razing of the memorable, if not loved, “Shower Towers.”

Mar/Apr 2007 Donald Maurice KreisAn architectual era ends with the razing of the memorable, if not loved, “Shower Towers.”

Mar/Apr 2007 Donald Maurice KreisAn architectual era ends with the razing of the memorable, if not loved, "Shower Towers."

AT THE DEDICATION CEREMONIES for Bradley Hall in November 1961, President John Sloan Dickey '21 weakly proclaimed that the building was "a fine structure." Math professor Martin Arkowitz offered similarly faint praise.

"When I first came to Dartmouth in the 19605, Bradley Hall was just a few years old," Arkowitz recalls. "It was very nice to move into a new building. I felt that it served my purposes and the departments purposes very well." His only complaint? The offices were too small to host more than one visitor at a time.

The razing of Bradley and its sister building, Gerry Hall, began last December. The buildings, formerly and not always affectionately nicknamed the "Shower Towers," were demolished after serving as headquarters for the math and psychology departments for nearly 45 years. Their replacements—Kemeny Hall for math and Moore Hall for psychology were designed by high-profile architects. Moore Ruble Yudell, whose firm was designated the 2006 firm of the year by the American Institute of Architects, designed Kemeny, and Robert A.M. Stern, who is generally considered the top purveyor of historicist architecture in the nation, designed Moore.

The Shower Towers earned their nickname because of the turquoise, blue, gray and white glazed ceramic tiles that adorned sides of both structures. For local architects E.H. and M.K. Hunter, these colorful decorations did not serve as a tribute to bathrooms, but rather represented an unprecedented step away from brick neoclassicism.

Marlene Heck, a senior lecturer in the art history and history departments, describes Bradley and Gerry as part of "a self-conscious effort to nudge the rural College toward a more urbane, postWorld War II modernism." Central to the notion of urbane modernity was the idea that new materials would find their place in American buildings, thus transforming their appearance. Not only did

Bradley and Gerry feature pre-cast concrete panels faced in ceramic tile, they also boasted insulation made of a geewhiz new product called Styrofoam, donated by the manufacturer as a way of promoting its use.

This optimistic sense of change allowed the architects creative freedom to forgo traditional ideas in their arrangement of space on floor plans. Unfortunately, the excess faith in modernity ultimately hindered the towers' construction. Budget, of course, is the eternal sword of Damocles for architects, and Bradley and Gerry suffered from the thoroughly erroneous theory that as a result of these newfangled materials it was feasible for an inexpensive building also to be great.

Their construction cost a relatively low $1.45 million, or about $9.75 million in today's dollar. As a result, the connecting walkways of Bradley and Gerry were poorly engineered, leaving them drafty and unwelcoming. The hallways, lined with a rich brown terra cotta, were gloomy and institutional because of the lack of natural light. Ceilings were too low, creating a sense of claustrophobia. And the innovative brise-soleil panels over the windows, whose shade-giving virtues make them popular in todays new "green" buildings, tended to fall off during storms.

All of which, regrettably, has given non-historicist design at Dartmouth a worse name than it deserves. The local chapter of the American Institute of Architects bestowed Bradley and Gerry an award for design innovation, and rumor has it that the document hung in the mens room of the Colleges facilities management department, which is symbolic of Dartmouth's ambivalence toward the buildings.

As they come down, parts of the Shower Towers may be more popular with the community than the buildings ever were intact. The College has had requests for the 400 cubic yards of granite cladding it retained from the demolition, in addition to requests for the tiles themselves, which, sadly, don't lend themselves easily to salvage. The College hopes to save a couple dozen of the fragile tiles and preserve them for posterity.

Professor Arkowitz, now happily de- camped to Kemeny Hall, remains somewhat indifferent to the ceramic. He says the view from the inside of his old quarters wasn't as controversial as the view from the outside. "The looks of the tiled tower never bothered me," he recalls. "I spent most of my time inside the building and could not see it."

DONALD MAURICE KREIS is an attorney and former news reporter. He writes aboutarchitecture from his home in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

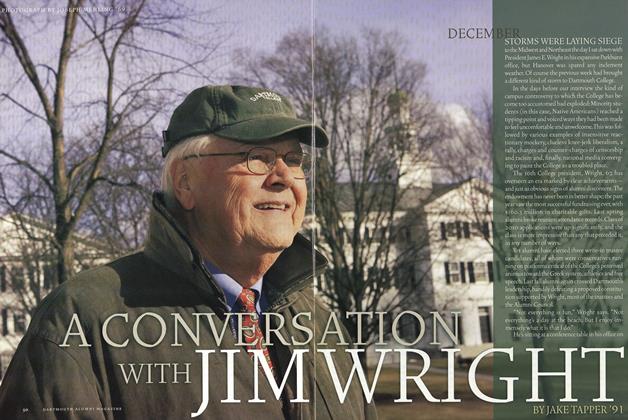

FeatureA Conversation With Jim Wright

March | April 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

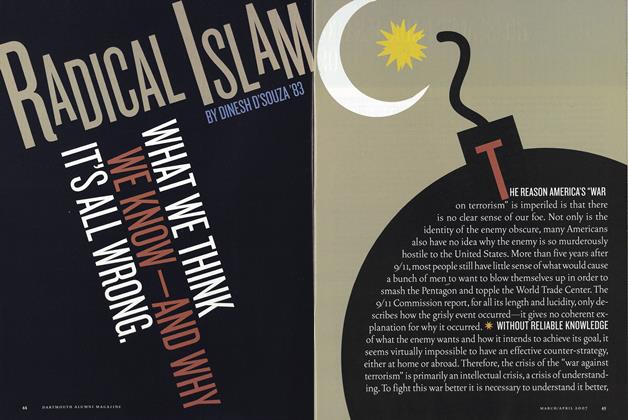

FeatureRadical Islam

March | April 2007 By DINESH D’SOUZA ’83 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

March | April 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2007 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2007 By Scott Listfield '98, Scott Listfield '98 -

TRADITIONS

TRADITIONSBook of Mystery

March | April 2007 By Julian Kesner ’00