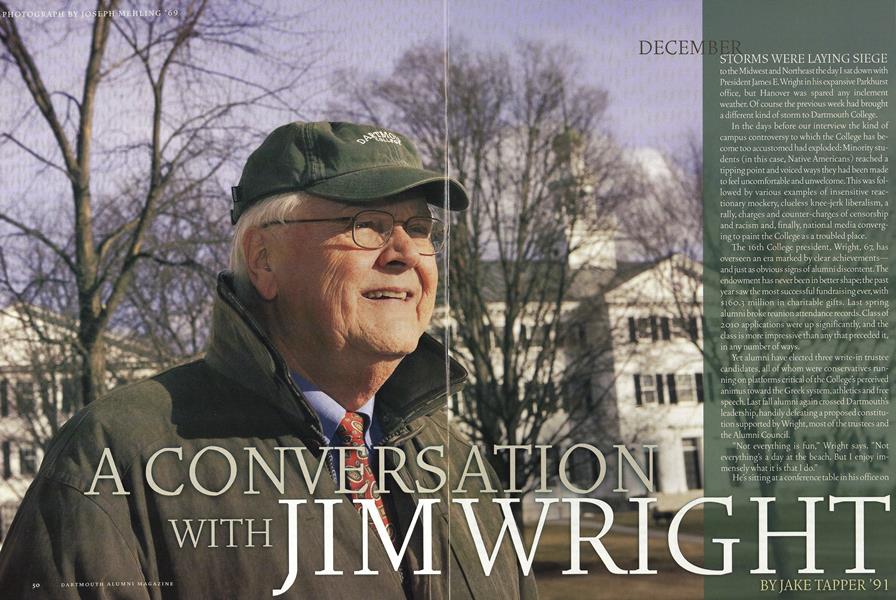

A Conversation With Jim Wright

Trustee elections. A failed constitution. Campus unrest in the fall. Athletics, academics and fundraising. Dartmouth’s 16th president weighs in on these and other topics in a wide-ranging interview.

Mar/Apr 2007 Jake Tapper ’91Trustee elections. A failed constitution. Campus unrest in the fall. Athletics, academics and fundraising. Dartmouth’s 16th president weighs in on these and other topics in a wide-ranging interview.

Mar/Apr 2007 Jake Tapper ’91DECEMRER

STORMS WERE LAYING SIEGE to the Midwest and Northeast the day I sat down with President James E.Wright in his expansive Parkhurst office, but Hanover was spared any inclement weather. Of course the previous week had brought a different kind of storm to Dartmouth College.

In the days before our interview the kind of campus controversy to which the College has become too accustomed had exploded: Minority students (in this case, Native Americans) reached a tipping point and voiced ways they had been made to feel uncomfortable and unwelcome. This was followed by various examples of insensitive reactionary mockery, clueless knee-jerk liberalism, a rally, charges and counter-charges of censorship and racism and, finally, national media converging to paint the College as a troubled place.

The 16th College president, Wright, 67, has overseen an era marked by clear achievements— and just as obvious signs of alumni discontent. The endowment has never been in better shape; the past 1 year saw the most successful fundraising ever, with $160.3 million in charitable gifts. Last spring alumni broke reunion attendance records. Class of 2010 applications were up significantly, and the class is more impressive than any that preceded it, in any number of ways.

"Not everything is fun," Wright says. "Not: everything s a day at the beach. But I enjoy immensely what it is that I do."

He's sitting at a conference table in his office On the second floor of Parkhurst, his 6-foot-4-inch frame leaning back casually in a wooden chair. "When I came here in 1969 I had a little office over in Reed Hall where, if two students came to see me at once, we had to move outside because there wasn't room for three of us in that space together," Wright recalls. "I never for a moment imagined when I came here that I would be over in what was then John Dickey's office, sitting behind his desk."

Wright is an unlikely candidate for the liberal, elite, Ivy League president-bogeyman that some of his opponents see him to be. He grew up in Galena, Illinois. His father tended bar; not one of his grandparents achieved a high school diploma. With college not an apparent option, at 17 Wright enlisted in the Marines. (These days Wright occasionally visits wounded soldiers being treated at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.) Discharged honorably three years later, Wright enrolled in what is now the University of Wisconsin at Platteville, going to work at the zinc mines in his hometown to help make ends meet. On his Parkhurst desk sits a heavy chunk of lead from one of those mines, atop which sits a small knife he once used to carefully remove the paraffin covers from dynamite.

Wrights has been a meteoric rise: from history professor to dean of faculty to acting College president (during a sabbatical taken by the late President James O. Freedman) to provost to president.

When he was inaugurated, in April 1998, Wright said he'd been around the College so long that approximately 5 percent of all living alumni had taken one of his classes (I was among that small group, having taken my first history class with him in 1988). Despite that familiarity, Wright—taking on the challenges of the Greek system, diversity and myriad other explosive issues that mark university life in the 21st century—has had to occasionally handle himself with the delicacy needed to remove paraffin.

In the last few years three petition candidates have won seatson the board of trustees, and the new constitution supported byyou, the Alumni Council and most of the trustees was handilyrejected. Where did you all lose the alumni?

I'm not sure the vote on the constitution was a referendum on the board of trustees or the council or the administration. Certainly the three trustees who opposed it were very careful not to frame it as a test case on the direction of the College. So I don't read it that way, though there's no doubt that some people voted against the constitution because they wanted to send a signal that they disagree with the direction of the College.

You endorsed the constitution, right?

I did endorse it. I thought it was an improvement that would advance the operation of alumni governance. It lost by a pretty firm margin. But if people intended it as a referendum on me, I didn't understand it that way.

What about the three petition trustees?

There's no doubt that, beginning with T.J. Rodgers and then with Todd Zywicki and Peter Robinson, they were running against what they perceived to be problems with the College. They were running for certain values they argued had to be articulated within the board of trustees, and they won on that basis. I've developed a good relationship with each of them and work closely with them. We're candid with each other. Rodgers, in fact, is a friend. There are parts of the world that we see differently, but I don't know that we've ever had any disagreement on the direction of the College or the way we see Dartmouth.

Could the constitution vote have been a referendum about someof the things alumni see happening at Dartmouth?

We do surveys of alumni periodically and there is pretty consistently a group of 10 to 15 percent of alumni who are dissatisfied. Some of them were dissatisfied the day they walked off the campus. Some of them are serially dissatisfied—I don't mean that in a condescending way but there are people who have demanded my resignation, and I take comfort in knowing that they have demanded the resignation of every president going back to John Kemeny. So I'm in a good, rich tradition there.

But there are those who are upset about things that they see happening with the College today. And I think we have to do a better job of explaining to them. When people seem to believe certain things are happening at the College that aren't happening, we can't find an effective way of communicating with them and of understanding why it is they believe that.

Such as?

Such as the belief that we no longer value teaching, when it is at the center of Dartmouth's strength. I can only affirm so often my own values and beliefs, and if that's not finding a resonance I'm not sure what more I can do about that.

However you interpret the voting results, don't they show thatthe trustees and Alumni Council are out of touch with alumni?

Sure, and I think there is a disconnect. I'm not sure that the board of trustees and the Alumni Council and the alumni governance task force ever effectively communicated what it was they were trying to do. The whole campaign got caught up in a lot of accusations and rhetoric flying back and forth. The insistence that the new system would be less democratic had some resonance with alumni, who care about protecting democracy and participation. That was wrong. Ironically, there are greater opportunities for democracy and participation under the proposed constitution, but it failed. We do have to take quite seriously what that says. There was a pretty good turnout for that vote.

The best ever, right?

Yes. It underlines the major need for us to communicate and listen better. That's what I learned from all of this.

Maybe alumni like petition candidates and didn't want to changethat dynamic?

The current dynamic does advantage petition candidacies, where you've got three people dividing the vote against a petition candidate, and that's simply a fact of life. I think the petition candidates who were elected under the current system likely would have been elected under the new system. Rodgers certainly would have been, so that's not an issue. The thing that I'm concerned about is how much is electability going to be a criterion that we use when looking at board nominees? The Alumni Council has nominated three exceptional candidates for the board of trustees. It's hard for me to imagine people saying that we can improve upon these candidates in terms of what they can do. They're not people who are "insiders," They're people who have independently established themselves and are doing remarkable things in their own lives. Yet I predict there will be a petition candidate running agaifist them, because it's a means now of running for a seat on the board. Have we institutionalized a way of conflict? Have we institutionalized a party system? And is this the way we want to govern?

Is there a constituency that feels the Alumni Council never picks anyone whom that constituency wants to serve on the board of trustees? A constituency that thinks, "Why wouldn't petition trustee Todd Zywicki be one of those officially nominated candidates? He's a law professor, he's a brilliant man, he's a nice guy, he bleeds green." The only thing they can think of that may be considered a strike against him is that he's a Republican.

Well, first of all, Todd Zywicki is all of those positive things you said, and he's been a good colleague on the board and I enjoy having Todd on as a member of the board. But why couldn't Todd have gone through the regular process?

Maybe the Alumni Council never would have considered him. We don't know that, do we?

We don't. But clearly there's a constituency out there that feels the Alumni Council is picking like-minded folk and would not want to put a conservative on the board.

That view would hold that the interest for this dissident group is that we need to have more conservatives on the board.

Or more people in favor of protecting the Greek system, protecting athletics, emphasizing undergraduate education and free speech, which seems to be the platform of all three.

It is the platform, but all of these things the College does exceptionally well, so there's not a disagreement. Some colleagues on the board have been a bit startled, if not amused, to hear that they are considered left-wing for the first time in their lives. This is a pret- ty conservative board.

For alums paying attention to campus activities in the fall, this is what they see: minority students upset; The Dartmouth Review upsetting them even more; charges and counter-charges of political correctness, racism, stifling of free speech, insensitivity; an athletic director saying things that, charitably, in the view of many alumni, can only be interpreted as odd; and, ultimately, Dartmouth getting more negative publicity because of a handful of students. Can you understand why this might upset alumni—of all political stripes—and make them think the College is on the wrong track in any number of ways?

Yes, I can. There are a lot of pieces to this. Part of the problem has to do with picking up pieces of these things in the press. People have an insight or one fact or one piece of information or an interpretation of that piece of information.

Let me try to go through the whole thing as a case study of how things happen in a place like this. I have a long history with the Native American issue. I came here in 1969, and John Kemeny recommitted Dartmouth to Native American education in March of 1970.1 took it seriously and became involved on the faculty committee that set up the Native American studies program, which recruited Michael Dorris to teach. I taught the American West history course, and I worked with some of the first Native students who were here to try to get Dartmouth to discontinue use of the Indian symbol. I met with the Alumni Council in 1973 or 1974 on these matters. And most people were quite responsive. Alumni who had used this symbol over the years were not looking to hurt anyone— they were surprised that people were hurt by it—and there was a good conversation there. There are still people who insist they're going to use that symbol, they're going to use that theme, and that's what they do.

This fall there were a series of incidents that really had a lot of Native American students feeling they were not welcome at Dartmouth. These kids were deeply hurt. That's why I spoke out in a letter and at the rally in November. My theme and focus was about this community and about all of us having an obligation to make others feel welcome here. That's in the best tradition of Dartmouth.

Dartmouth does not belong to any group, even though there are a lot of people who assert ownership over it. But the Native American students clearly have every right to assert that this is their college. They go back to the charter of 1769, when Dartmouth was organized for the purpose of providing education for them. They should not have to feel like outsiders here. And I don't want them to.

I don't want any group to feel as outsiders here, including conservative students. We're not going to censure people for what they say or wear, we're not going to have speech codes, we're not going to have dress codes. We believe fundamentally in free speech—we're going to preserve the Hovey murals when we finally tear down the Thayer Dining Hall.

What's going to happen to them?

They're going to go to the Hood Museum for displays and other things.They're going to be protected and preserved.

Why?

There is a creation myth that evolved in the 1920s and 1930s that they represent. It has nothing to do with the organization of the College but, as an historian, I'm not going to start destroying history. That's part of the Dartmouth creation myth, at least for some generations of Dartmouth graduates, and it deserves to be protected and to be part of this place.

Can you understand the perspective ofthose who say, "If the Hovey murals areoffensive, certainly there are Christianswho are offended by the Orozco mural inBaker Library of Christ tearing down thecross?"

The Orozco murals were of great controversy in the 19305. President Hopkins took a lot of heat for that. And he was firm that these were works of art and they were going to be protected. I would say the Hovey murals are works of art and they're going to be protected. We don't destroy history here. We're not the Taliban. Is Dartmouth sensitive to groups who are here? Yes. It doesn't mean we bend to every whim—some people have asked us to destroy the Hovey murals, but we're not going to do that.

Why does Dartmouth seem perpetually inthe middle of these crises and debates?

Dartmouth is a microcosm of American society; these things are being played out elsewhere. We're in a small, intense, close community where these matters get worked out much more aggressively. It's a place that has a long history of sharp elbows, but fundamentally this is a place where the students are happy with the College, where they're getting an exceptional education. We have some issues that have no easy answers. But we are going to protect free speech.

You got into a back and forth with a free speech coalition—Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE—that criticized the College for not having a free speech code. One of the reasons was a 2001 incident in which a dean received a copy of a Zeta Psi fraternity newsletter containing demeaning and obscene comments about women undergraduates and the College de-recognized that fraternity.

That's right, FIRE looked upon that as a matter of free speech.

How is it not?

Its not a matter of free speech because this fraternity had done this before. They singled out specific women students, accused them of the most gross things in publications, and these women were terribly upset. I guess it's surely free speech to publish pornography, and that happens. But I think in a community like this, it's quite appropriate for the College disciplinary system to say we do not think this organization, is meeting our expectations on this campus. As far as I know there's still a fraternity over there—I walk past it every day, there are lights on in the house—but they've been derecognized. No student was individually disciplined for what they did. That maybe a fine-point distinction, but I think it's a terribly important one. We had some conversations with FIRE. I made some pretty strong statements on free speech that are consistent with what I've said over the years and FIRE did back off from their condemnation of us.

What about the letter from Athletic DirectorJosie Harper apologizing for schedulinga hockey game here with theUniversity of North Dakota team, whichis known as the Fighting Sioux?

Thar came in the context of a lot of students here feeling very much unwelcome and thinking that the institution was not supportive of them. When Josie Harper sent the letter out to the students that was published in The D right before Thanksgiving, she really was looking to that as an internal communication. Obviously there is no such thing and Josie now recognizes that.

Is it going to be the policy of Dartmouthto no longer play teams that have mascotsoffensive to minority groups?

We have no interest right now in developing that sort of a policy. I did ask a faculty member to convene a group of people and look at what we're going to do so we don't find ourselves suddenly stunned when a team coming in here has that.

Is Dartmouth a hostile place for Native Americans?

I don't think so. But I understand that several events have made Native American students feel incredibly uncomfortable and unwelcome. They needed other students to speak out, to grab them and say, "We're with you, we understand you." I think that has happened. Native American students here face a different set of issues and problems than most students. And I don't like it when students here make them feel like outsiders.

What do you think motivates The DartmouthReview to publish an issue with acover depicting a Native American holdinga scalp and the title: "The Natives Are Getting Restless?"

You'd have to ask them. They have always enjoyed satire as a means of ridiculing their opponents, which sometimes can be very effective. Sometimes it can fail. The Review, over the many years that they've published here, has had some exceptional young journalists. Hard-edged, to be sure. But I've always found it troubling that the way to advance a point of view is to ridicule somebody- who holds a contrary point of view. I don't think that's a useful way to have a dialogue. If you look at the major controversies over the years involving The Review, they've been about people feeling deeply insulted. This is my campus and my community and I want everyone to feel safe and secure here. It doesn't mean that they're never going to be insulted or hurt—that's part of life. But it's my responsibility to say, "You are safe and secure." And if The DartmouthReview felt unsafe and insecure, I think it would be my responsibility to say, "You, too, are welcome here. You, too, need to feel safe and secure here."

Where do you draw the line between wanting students to feel safe and secure, and protecting free speech?

We cannot be Big Brother. We cannot protect you from everything. Students have to speak up to other students and for other students. If you find a place that's hostile or offensive, don't go there. This is the message I stress all the time: Students need to police other students.

How is this place different in 2007 thanit was 20 years ago from the perspectiveof a gay student, a female student and ablack student?

My own assessment and the assessment I get from survey data and other sources is it's a far more hospitable place for each of those categories of students. It's not yet sufficiently supportive and encouraging of them as it appears to be of white male students.

We need to think about what we can do better. Women are far more comfortable, but there are still places and locations where they don't feel as welcome as they have every right to be. Gay students probably have in many ways come the greatest distance.

One incident in the fall turned out to bestudents from a local high school yellingracial epithets at black Dartmouth students.Awful, but that has nothing to dowith the College. What can Dartmouth do?

We have to continue to remind people that we can't be "other"-ing students. We need to continue to encourage students to work with students. There are things that the College can do, but it's not engineering relationships and it's not engineering how students relate to and interact with one another.

Why has diversity been important to you?

It's hard to think of an elite and privileged institution—of which we are one—that does not open its doors to students from all backgrounds and experiences. It's a matter of justice. The fundamental value is what students learn from other students. We all seek out friends who are most like us. Because in a hectic, intense world we need to lay back and relax. And there's nothing wrong with seeking out those who are most like us, but we don't learn very much when we're with those who are most like us. Where we learn is where we're with students who will say, "Why do you like that music? Why do you believe that? Why did you vote that way? Why do you want to do that with your life?" It's essential that we continue to be a place that really represents the richness and fullness of American life because this is where students can learn.

Does that include ideological diversity? Is there a charge to bring in students—home- schooled, perhaps, or Mormons, or the children of military—who are unlikely to have a liberal, secular perspective?

There certainly is an intellectual range at Dartmouth. Our admissions office would not expect a liberal or a secular perspective. Dartmouth is, after all, a place that has had a pretty vibrant conservative tradition for many years. What we don't do, what we can't do, what I would hate to see us do, is look at entering students and say, "What are your political values? What is your ideology?" and make choices based on that.

Conservative students often express thefeeling that their ideology is not welcomeon campus, that the faculty is over-whelmingly liberal.

There's no doubt that as a group—not at Dartmouth but nationally—faculty are more liberal than is the population as a whole. I want to make certain that's not something that spills over into the classroom. There was a national study done a couple of years ago that showed that on some matters having to do with, say, taxes, faculty were somewhat more liberal that the population as a whole. But where they really varied from the population was with the social issues—gay rights, choice for women, affirmative action. I ask students, "Does this show up in the classroom?" A very conservative student friend told me a couple of years ago he never had any problem in the classroom. Now that's one student, and he's talking to me. But I do ask about this. If you look at our departments where matters of public policy that would be relevant, perhaps, to ideology are discussed—government, economics—certainly there are conservative voices in those departments. So we need to continue to watch it, but we can't start having an ideological or a partisan litmus test on the faculty we hire or the students we recruit. To say it's time for us to bring a half-dozen Republicans into the philosophy department is not the way to recruit philosophers. No more than it would be to bring in some Democrats or some Libertarians.

How much of your job involves raisingmoney?

I don't know—25 percent? I travel probably pretty near every week. Most of my travel is to New York—if you're raising money, it's a good place to be. I try not to be gone for more than a single night. I want to be on campus, I want to walk over to Collis, I want to go to athletic events. [My wife] Susan and I like to go to any number of student activities. We go to concerts and plays, we go to Thayer Hall sometimes for dinner, just sit down with students at a table and talk to them. This is the old professor part of the job that I enjoy immensely. A lot of college presidents wring their hands about fundraising. I've never done that. It's demanding, it takes a lot of time, it sometimes can be tiring. But I have tremendous ambitions for Dartmouth. Like having financial aid for all of our students. I want to make certain that we can protect the faculty that makes Dartmouth the kind of institution that it is. So I'll never balk at being out and trying to meet people and trying to raise money for Dartmouth.

How much easier would your job be interms of fundraising and dealing withalumni if we had a winning football team?

It would probably be easier on the margin. Alumni aren't saying as a group that we always have to have a championship football team, but football becomes the barometer here. People who don't necessarily follow football closely get teased at the water cooler Monday by their colleague who went to Harvard. They don't like that. They want to tease their colleague from Harvard about Dartmouth having beaten them. Dartmouth football has been the most successful program in the history of the Ivy League, and we became accustomed to being in that position. I'm a fairly competitive person and would far rather see us succeeding. I have confidence in Buddy Teevens and I think the people who really follow football closely know Buddy's turning it around. He had a good team this year that was just ayard short a lot of times.

What do you say to alumni who say thatyou don't value athletics?

I say that they're wrong. I say that they're not doing their homework. I would be willing to argue, with the exception of football, that across the board Dartmouth athletic programs are stronger today than they've ever been. We had two soccer teams last fall that were in competition for Ivy League titles coming in to the last weekend. The men's team had won it two years in a row, the women's team was poised to go into the nationals. Both of our hockey teams coming into the winter were ranked nationally. The men's team has had the best two- or three- year run of any two or three years in Dartmouth's history. The women's team has been in the Final Four three of the last four years. The women's basketball team has won more titles and more championships than any other team in the Ivy League. They won again last year and they're ready to go again this year. Terry Dunn is turning around the men's basketball team. We have not won since 1958-'59, but I told Dave Gavitt a member of that team] a year or two ago that his days of saying "last trophy" are overwe're going to do that, and Terry Dunn will do that. We have lacrosse teams that are ranked nationally. The women's lacrosse team played for the national championship last year against Northwestern, the men's team has turned it around after some mighty lean years. Men's baseball is an exceptional program. Bobby Whalen does extremely well in recruiting and he's in it right down to the last week every year.

What about athletic facilities?

We probably will have invested over $70 million in athletic programs and facilities under my presidency. Every single athletic facility will have been upgraded or replaced in my presidency. I'm not sure that's happened any other time. I have a commitment to athletics and anyone who wants to test it can go over to the athletic department and ask the players or the coaches whether they think the institution is behind them. We are.

I suppose it isn't an unusual role for a collegepresident to take heat for teams' performances.Probably you could com-miserate with your predecessors except,with the death of James O. Freedman lastMarch, all of them have passed away.

All of a sudden I was alone in the Wheelock succession. I'm not at all suggesting it's a lonely place to be, but in the past I could talk to David McLaughlin and Jim Freedman about things. They never told me how to handle a situation, but I could try things out with them and talk with them. And now I don't have anyone who had quite the same experience that I'm having.

What's been your worst day on the job?

Dealing with student death is always so difficult and traumatic. We haven't had a lot of them, thank God, but we've had a few. Then there was the killing of two faculty members, two friends—professors Half and Susanne Zantop. I will remember forever that phone call I got at night, that something had happened there. Just how traumatic it was for the community and the way that we had to try to work through that.

And 9/11 just took all of us aback. I was trying to find out if there were Dartmouth people affected. And I have three children, two of whom fly a lot. I was trying to be president yet I was also trying to find a way to get in touch with them and make sure they weren't on one of those airplanes. You don't like to find wonderful stories in tragedies, but we had a couple hundred students out along the trails on freshman trips when 9/11 happened. So we got the Dartmouth cross-country and ski cross-country teams and we sent runners out along the trails. So by mid-afternoon along streams and trails throughout northern New Hampshire kids were sitting down with the groups and explaining what had happened. If any of them had families that worked in those buildings or some other connection or for some other reason they wanted to come home, they were taken out. Susan and I went up to talk to the rest when they came back to the Ravine Lodge, I think it was the next night, to talk to them there. That was a difficult time.

What's been your best day on the job?

I don't know that I have a single best day. I love the ceremony of commencement, but there's also a bittersweet part of that. I love the beginning of a new school year. My inauguration was a wonderful occasion, to have my mother here, who was very proud of her son. She had been telling everyone on the way out here, in every airport, that she always knew that I would amount to something and she was the only one who believed that. And here she was.

What's been your biggest frustration onthe job?

The inability to communicate effectively with alumni about what we do at Dartmouth and the strength of Dartmouth. We clearly are not doing it well. I realize there are no real forums for me to communicate just the magic of this place, the way that students think about Dartmouth, their feelings toward the College and each other, their caring for the sort of college that Dartmouth is.

Why haven't you been able to communicateas well as you want?

There's a level of cynicism or suspicion that's part of American life today and we have to recognize that. John Dickey could speak and it would be a voice coming down from a mountaintop. I'm not certain that today any voice can have that sort of authority, and surely mine can't, nor would I want it to. I enjoy the give-and-take so much. But I'm not sure we have enough opportunities for give-and-take. I learn a lot when I talk to alumni.

Many alumni were concerned in 1999 when you and the trustees introduced the Student Life Initiative to change out-of- classroom life for Dartmouth students. What's the status of the initiative?

We accomplished most of the things we set out to do.

And has Greek life changed?

Significantly. The Greek system at Dartmouth now is stronger than it's ever been, in the best sense of that word.

It seemed you were going to try and do away with the Greek system.

Sure. And I think that we stumbled badly coming out of the box. What we tried to do was start a process and it was interpreted as a conclusion. We ended up needing to clarify, and when you start having to clarify before the end of the first day, you know that you're in trouble. It was a serious mistake on our part to sort of announce that process the way we did. To surprise people. To give a sense of closure when we were really trying to initiate something. It's taken awhile to recover from that. The students are not suspicious and, to my knowledge, we have a good working relationship.

How has Greek life changed?

The people who work with the Greek system insist that it is far more accessible. Seniors say its far better than when they were freshmen. Just a more open and energetic culture and environment. I think the leadership is stronger, we've got more alumni leadership involved- I think that's an important thing for the system I think in terms of membership they continue to be strong. Most of the houses are in pretty good shape financially.

Were you in a fraternity?

No. I was in the Marine Corps. When I started college at age 211 was working as a bartender and working as a janitor and working in the mines. I didn't have time for that part of college life.

Do you see anything inherently wrong withpeople joining fraternities or sororities? No.

There seem to be a lot of faculty memberswho do think so.

There are. And I don't agree with them. Sometimes there are things wrong with individuals who have joined them, and I think they should to be held accountable for their conduct, just like organizations need to be held accountable for their conduct. The mistake is to generalize about the system. Anyone who follows closely this system here knows that to simply say there is a Greek system is to be guilty of over-generalizing.

It's been difficult. The tension always is around alcohol. The Dartmouth I came to in 1969 was a different sort of place. With the 18-year-old drinking age people could drink and nobody cared about drinking ages that much anyway. As a faculty member you'd go over to fraternities, students would invite you over on Friday evening for "faculty'tails" and you'd talk with students and have a beer with them. It was a far more open environment and if I could do anything, I'd return to the 18-year-old drinking age. But that's not an option that we have here.

What's happened over a period of time is there's been a recognition of all the negative consequences of abuse of alcoholconsequences for yourself as well as for others—and, most importantly, the government has become far more demanding of institutions. So Dartmouth is not a free agent about making decisions about what our students can do and cannot do. We cannot countenance a system where students are flagrantly disobeying the law. The state of New Hampshire is particularly strict in that regard. They watch things pretty closely. So the College finds itself institutionally in the middle of very complicated situations. As long as there have been young people and drinking ages people have been skirting the drinking ages. For all the things this college does well, policing behavior is the worst. And I'm glad of that, I don't want to start policing behavior, I don't want to start saying, "What's in your cup?" and "Let me smell your breath." And we don't do that. But it's a changing time in terms of accountability and in terms of vulnerability to litigation and to challenges and in terms of recognition that somebody could be seriously hurt. So we're put in a difficult spot.

Susan and I live in the middle of Webster Avenue, and I assure you I do not go to bed every night worrying that some place out there somebody's drinking beer and having a good time. I'm glad they are. I hope they're okay, though. I hope they're looking out for each other. And I hope that Dartmouth and the organizations are not putting themselves ever in a spot where they're at risk.

Do they keep you up at night?

No. I think that's part of the folklore here. There are times when they can keep you up. In the spring when the parties move outside it can get pretty noisy. Sometimes you can turn on the fan and not hear the music. Sometimes you can feel the music. The thump of the bass can make all your internal organs thump with it. I've had those sorts of experiences but by and large they're really pretty good neighbors.

You've got the final report you commissionedtwo years ago from managementconsulting firm McKinsey & Cos. on how tobetter run Dartmouth administratively.What do you hope this report will help youachieve?

Three things. One was to look at the administrative culture here and communications and figure out how to coordinate our activities better and make it as collaborative a place administratively as it is for students and faculty. I want to empower middle-management more, I want to give them more responsibility and hold them more accountable. Secondly, we want to take a look at whether our hiring system is too cumbersome. And then the whole budget process, how we relate budget to strategic objectives—do we do that well enough at the middle and lower levels of the institution? McKinsey also found that the size of Dartmouth's administration was not out of line with that of our peer institutions and that it had only grown modestly—that was good, but not surprising, news. During the period under study the faculty had grown by 3 percent per annum and the administration by 1 percent. We are now following up on a number of changes that stemmed from the McKinsey work.

Including a new mission statement?

Yes. Quite frankly, when McKinsey and others started talking to me about a new mission statement last year I found it a bit troubling. Like most people who have been involved in conversations about mission statements, I find them very difficult processes. You end up arguing about the wrong adjective or adverb here, where the comma should go and, finally, you end up with lowest-common-denominator abstractions defining what you're trying to do. And then people happily ignore it when you've completed it. I want something more succinct and more aspirational.

One paragraph?

Yes. I started meeting with various groupsstudents, faculty, administrators both senior and junior level, administrative assistants, union members, local alumni—and basically I said, "Let's talk about the core values of Dartmouth. I want you to help me understand: What are those values that at their best define Dartmouth at its best? Let's not go into an assessment as to whether we always meet our highest aspirations, but what defines us?"

Once we've got comments on our draft I'll go to the board and ask them to sign off on it. Then I'll talk to the various administrative groups here and say, "How do you relate to this and how are you going to advance our sense of mission and purpose?" It's a useful thing. Somebody told me it's not something you take on in this stage of a presidency, but it's something I've been energized by.

"THERE ARE THOSE WHO ARE UPSET THEY SEE AND I THINK WE HAVE TO DO A BETTER ABOUT THINGS HAPPENING WITH THE COLLEGE TODAY. JOB OF EXPLAINING TO THEM."

JAKE TAPPER is senior national correspondentfor ABC News and is based in its Washington,D.C., bureau.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRadical Islam

March | April 2007 By DINESH D’SOUZA ’83 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

March | April 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2007 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2007 By Scott Listfield '98, Scott Listfield '98 -

TRADITIONS

TRADITIONSBook of Mystery

March | April 2007 By Julian Kesner ’00 -

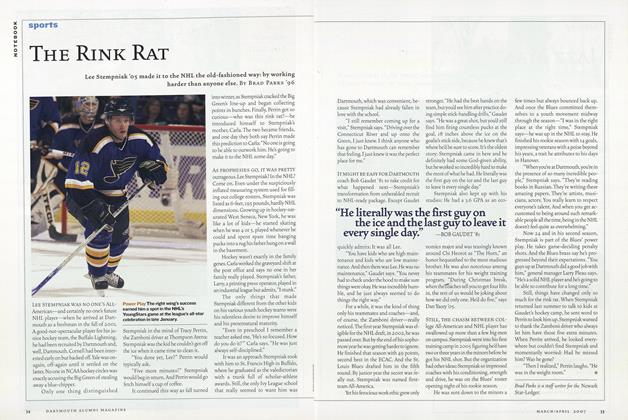

Sports

SportsThe Rink Rat

March | April 2007 By BRAD PARKS ’96

Features

-

Feature

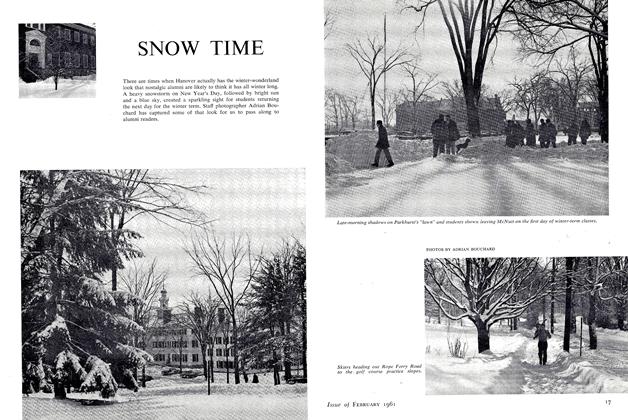

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureThe Friends' Best Friend

JANUARY 1964 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

Nov/Dec 2000 -

FEATURES

FEATURESSian Beilock

MAY | JUNE 2023 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

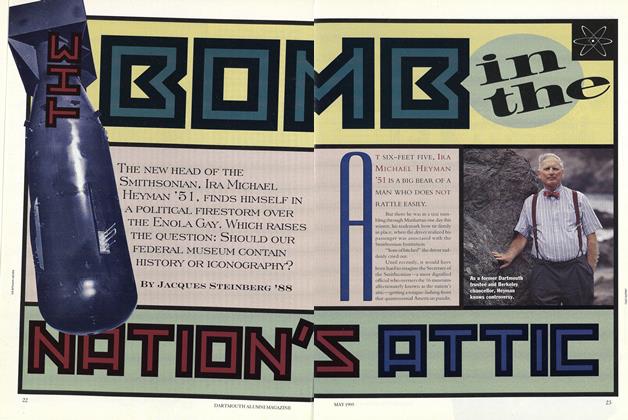

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Bomb in the Nation's Attic

May 1995 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2012 By Jennifer Caine ’00