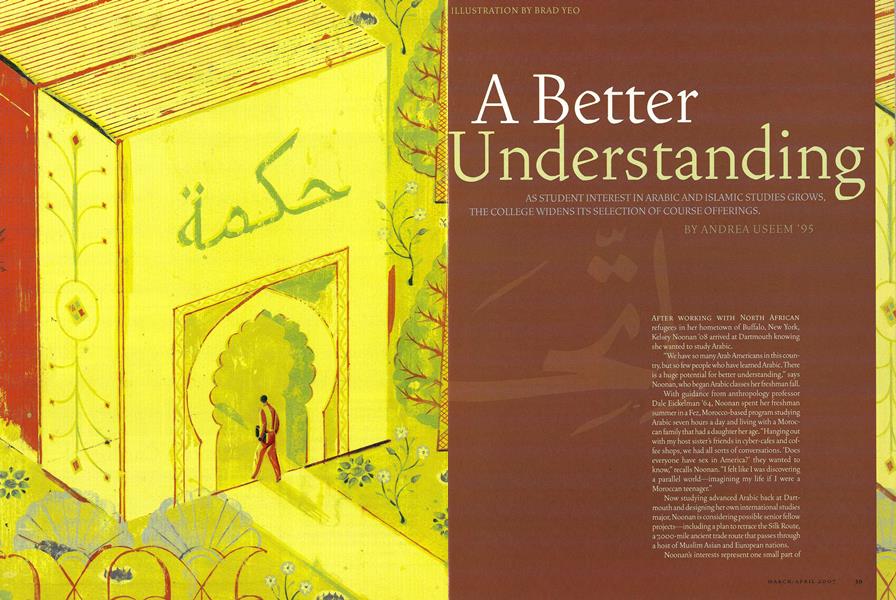

A Better Understanding

As student interest in Arabic and Islamic studies grows, the College widens its selection of course offerings.

Mar/Apr 2007 ANDREA USEEM ’95As student interest in Arabic and Islamic studies grows, the College widens its selection of course offerings.

Mar/Apr 2007 ANDREA USEEM ’95AS STUDENT INTEREST IN ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES GROWS, THE COLLEGE WIDENS ITS SELECTION OF COURSE OFFERINGS.

AFTER WORKING WITH NORTH AFRICAN refugees in her hometown of Buffalo, New York, Kelsey Noonan '08 arrived at Dartmouth knowing she wanted to study Arabic.

"We have so many Arab Americans in this country, but so few people who have learned Arabic. There is a huge potential for better understanding," says Noonan, who began Arabic classes her freshman fall.

With guidance from anthropology professor Dale Eickelman '64, Noonan spent her freshman summer in a Fez, Morocco-based program studying Arabic seven hours a day and living with a Moroccan family that had a daughter her age. "Hanging out with my host sister s friends in cyber-cafes and cof- fee shops, we had all sorts of conversations. 'Does everyone have sex in America?' they wanted to know," recalls Noonan. "I felt like I was discovering a parallel world—imagining my life if I were a Moroccan teenager."

Noonan's interests represent one small part of the engine driving the growth of Islamic studies at Dartmouth, a diverse field of study that has further blossomed since 9/11 called dramatic attention to the Muslim world. Dartmouth offers no Islamic studies major. Rather, students can find courses that touch on Islam sprinkled throughout the College, whether that means reading Naguib Mahfouz's 1988 Nobel Prize-winning stories of street life in Islamic Cairo (Comparative Literature 51: "Masterpieces of Literature from Africa"), exploring the influence of Malcolm X on the American civil rights movement (Religion 68: "Martin Luther King, Black Religion and the Civil Rights Movement") or listening for Muslim influences in modern Persian music (Music 40: "Ethnomusicology").

And the learning is not confined to Hanover. In addition to establishing the Asian and Middle Eastern studies department's foreign study program (FSP) in Fez, Eickelman has led the way in linking Dartmounth with the American University in Kuwait, the first private liberal arts college in the Persian Gulf, a parnership that opens up future opportunity for Dartmounth students to study or work in that region.

BEYOND ISLAM 101

For professors, discussing Islam in the classroom brings special challenges—and inspires creative solutions.

"When students walk into a class on Hinduism, they say, 'I don't know anything about Hinduism.' But when they walk into a class on Islam, they have to be deprogrammed from all the nonsense they've imbibed from watching Fox News and reading The New York Times" says Kevin Reinhart of the religion department, whose research has focused on pre-modern Islamic legal thought. As an antidote Reinhart has tried this tactic: "I string together scenes from movies and show how absurdly Muslims are depicted in the cinema. For example, Arabic comes up only when some fanatic is running down the aisle of an airplane with a bomb, shouting Allahu Akbar,'" he says.

Robert Oden, former chair of the religion department and now president of Carleton College, agrees. "You have to erase the slate before you start filling it in," he says. Oden would play videos of Pentecostal snake handlers or Jimmy Swaggart. "Then I would ask the students, 'If this is all you saw about Christianity, what would you think?' "

THE LANGUAGE BARRIER

While a majority of Muslims worldwide don't speak Arabic, the language remains an essential tool for unlocking not only Islamic religious texts but also the culture and literature of the Arabic-speaking Middle East. Interest in learning Arabic at Dartmouth has grown enough that last summer the College launched an Arabic language study abroad (LSA) program in Morocco, home already to Eickelman's FSP. "There is a war on right now," says Diana Abouali, assistant professor of Arabic. "In the area of language instruction, unfortunately, war is good for business."

First offered as a language in the 1980s, Arabic is attracting a growing number of students on campus, with enrollment in first-year courses jumping from 10 students in 1998 to 55 in the fall of 2006, according to Abouali. She expects the numbers to increase "as long as Iraq and instability in the Middle East remain a center of international political focus," she says.

Abouali, who first learned the lan guage from her Palestinian-born parents says some students of Arabic are interest ed in government-related careers, includ ing one student with an interest in publihealth in the Middle East (who recently in terviewed with the CIA at her mother' urging and was stunned to discover thi agency's senior Middle East representative didn't speak any Arabic). Others come to it almost by accident, such as the student who was struck by the beauty of Arabic calligraphy during a high school field trip. Then there is the ROTC student who, frustrated by the delayed introduction of the languages imperative case to the classroom, asked Abouali to teach him phrases such as "put down your gun" and to compile a handbook of military phrases. She referred him to the Army. "Sometimes I have to try not to think about how the language will be used," she says.

A full cycle of Arabic—two years or six Dartmouth termsopens up new possibilities for students, says John Voll '58, director of Georgetown University's Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (see sidebar, page 42). After two years of study a student "should have enough Arabic to wrestle with a newspa- per editorial and add an important dimension to a research paper," he says.

But learning Arabic isn't easy..One frustration for students is the gap between Modern Standard Arabic (or fusha), which they learn in the classroom, and colloquial Arabic (or ammiyah), which varies from country to country. "Students ask me, 'Why are we learning a language no one speaks?' I tell them Modern Standard Arabic is a lingua franca everyone understands, even if they don't use it," says Abouali.

LEARNING FROM EACH OTHER

Elshamy represents another new element in Dartmouth's classrooms: an increasing number of Muslim students. Some are from South Asia or Turkey while others are second-generation Americans or Canadians, according to Iran expert Gene Garthwaite of the history department. "Most [American] students think of Islam as alien," he says. "Then they discover that the students sitting next to them are observant Muslims, and the differences don't seem so different."

According to Richard Crocker, the Colleges chaplain and associate dean of the Tucker Foundation, among the i,100-odd incoming members of the class of 2010 about 18 people identified themselves on a questionnaire as Muslims; it was the highest number recorded to date. Last summer the office of religious and spiritual life hired its first part-time Muslim advisor, Irfan Aziz, who estimates there are roughly 60 active Muslim students at the College, in addition to another 20 or so in graduate programs.

lieve the prophet Abraham and his son, Ismail, first built the Kaaba [not pagans]."

Elshamy says that while friends and classmates sometimes call on him to "speak on behalf of the entire Muslim nation," in Morocco he found himself learning from other Muslims—in particular, his host-brother Badr, a 30-year-old who cooked and cleaned for his sister and ailing father.

"Sometimes Badr would prepare a huge meal, and his father would be grumpy and say, 'What's this?' But Badr was incredibly patient and loyal. It really showed me the importance of family in Arab culture," said Elshamy, who grew up in Manchester, New Hampshire, with an Egyptian-born father and Vermont-born mother.

While he enjoyed praying together with Moroccan Muslims at the mosque, Elshamy said he was happy to come home—and not just to drink the Gatorade he missed while overseas. "Islam in Morocco is very controlled; you can't feel comfortable speaking out," he says. "To me true Islam is being able to say what you feel and discuss it with others, and that's what we have here in America."

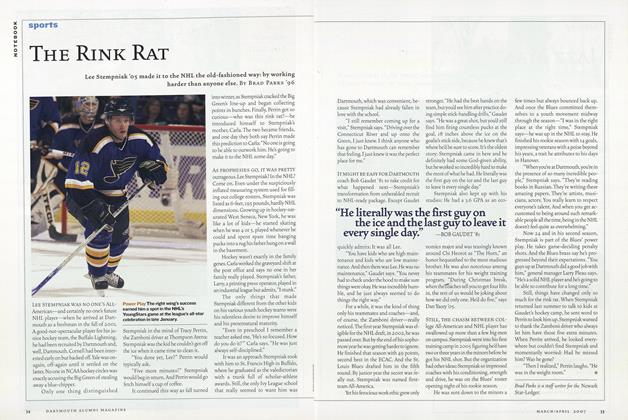

In Demand Professor Reinhart (left, with Eickelman and Abouali) says students taking Arabic act "like leaven, raising the level of courses and making other students aware that there is a richer world out there."

READING, WRITING AND ISLAM Professors'class descriptions reveal theavenues open to students interested in studyingIslam and Arabic civilization."Islam: An Athropological Approach"(Asian and Middle Eastern Studies/Anthropology) "focuses on Islam in practice, as it is lived by Muslims whose voices are seldom heard." 'The Eye of the Beholder: Introduction tothe Islamic World" (History/Asian andMiddle Eastern Studies) surveys Islam- ic culture beginning with the Prophet Muhammad, focusing on Ataturk, "and ending with a comparison of the medieval and contemporary worlds." "Writing Gender in Islamic Space"(Women and Gender Studies/Asian andMiddle Eastern Studies) invites students to study the work of writers and filmmakers from Egypt and North Africa. "Islam in North America: A Regional Variety of Islam" (Religion) challenges the notion that Islam is "the same in its essence whether in the Philippines or Philadelphia" by looking at the particulars of Islam in North America. "Arabian Nights East and West" (Comparative Literature/Arabic) is "an introduction to Arab-Islamic culture through its most accessible and popular exponent, The Thousand and One Nights."

"In the area of language instruction, unfortunately, war is good for —ARABIC PROFESSO business." DIANA ABOUALI

ANDREA USEEM is a freelance writer and editor who specializes inreligion. She lives in Reston, Virginia, with her husband and three sons.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

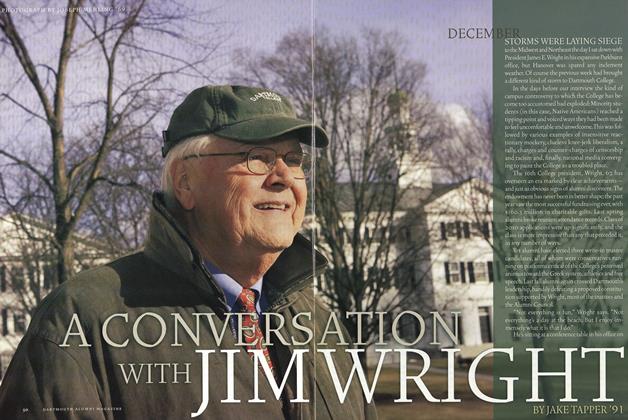

FeatureA Conversation With Jim Wright

March | April 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureRadical Islam

March | April 2007 By DINESH D’SOUZA ’83 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2007 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2007 By Scott Listfield '98, Scott Listfield '98 -

TRADITIONS

TRADITIONSBook of Mystery

March | April 2007 By Julian Kesner ’00 -

Sports

SportsThe Rink Rat

March | April 2007 By BRAD PARKS ’96