Healthy Choice

Jandel Allen-Davis ’80, DMS’84, trades private practice for a more public role in Colorado’s health care.

July/August 2007 LISA FURLONGJandel Allen-Davis ’80, DMS’84, trades private practice for a more public role in Colorado’s health care.

July/August 2007 LISA FURLONGJANDEL ALLEN-DVIS '80, DMS' 84, TRADES PRIVATE PRACTICE FOR A MORE PUBLIC ROLE IN COLORADO'S HEALTH CARE.

Jandel Allen-Davis recalls the day she visited a sixth-grade assembly-marking' Women's History Month and watched as she was portrayed by the blue-eyed, blonde daughter of a friend and fellow doctor: "When she stood there and concluded her story with, 'I am Dr. Jan.de! Allen-Davis,' tears came to my eyes." When Allen-Davis asked why the child had chosen her of all possible role models, her friend shrugged, "She thinks you're cool." A truism for sure, but Allen-Davis' takeaway was a little different. "It reminded me that you never know who's watching," she says. "I can remember going to a clinic as a child in Washington, D.C., and just staring at the few black doctors there. I wanted to tell them I was going to be one of them, I was going to be distinguished, too."

And so she of the most prominent black doctors in the Denver area and, as Kaiser Permanente (KP) Colorado's new associate medical director for external affairs, one of very few black female health care industry administrators nationally. "She's a superstar," says Cheryl Hara, director of the Colorado Board of Medical Examiners, on which Allen-Davis serves. Allen-Davis—an obstetrician/gynecologist well known as a public speaker, patient safety advocate, civic volunteer and board member who has served with organizations as varied as the Colorado Children's Chorale, Planned Parenthood and the University of Colorado Foundation—has been visible around Denver since moving there almost 15 years ago to: practice, and teach at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. Awards from publications and her peers hang with her diplomas in what she calls "my messy room" in her Highlands Ranch home, where she fashions painted and quilted silk art that has generated still more awards. "I'm taking them down," she says of her plaques and certificates, "to make this more of a rightbrained space." Several of her vibrantly colored pieces dot the walls elsewhere in the house, one of them just back from a show that toured the world for two years.

Despite her early desire to practice medicine—"as a kid I was always making medical kits to carry around," she says—Allen- Davis' path to medical prominence was not predictable. The seond-oldest of five children whose parents worked for the federal government, she is the only sibling who headed to college. "I was eager to move on and not look back," she says. She determinedly sought and gained admission to Washington, D.C.'s tony Immaculata Prep, then chose Dartmouth sight unseen. "I hadn't read the fine print," she says dryly of her surprise at finding herself in a maledominated institution in the woods. Being in a predominantly white school was nothing new, but the organized presence of other students of color was. "I was so excited to find there was an AfroAmerican Society the other kids thought I was nuts," she says.

Allen-Davis quickly embraced the AAS and after returning to campus from her LSA in Germany the spring of junior year, was elected as its first female president. "And, boy, did I get into trouble," she says, shaking her head. Separatist members questioned her leadership after she announced a series of teas that would bring white faculty members into the AAS house to discuss race relations. Her fellow students' animus caused her such anxiety that she lost 10 pounds. At a meeting where a vote on removing her from office was to take place, music professor Bill Cole, for whom she was a work-study student, and her boyfriend (now husband) Anthony Davis '82 and his friends showed up for moral support. "Bill just lit into the other members and no vote occurred," she recalls. "We wound up having the teas and they were well attended."

After earning a degree with highest honors in sociology from Dartmouth and graduating from Dartmouth Medical School, Allen- Davis did her internship and residency at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia before being assigned by the U.S. Public Health Service to practice on the Navajo reservation in Tuba City, Arizona, to repay student loans. "I went kicking and screaming and left kicking and screaming," she says. "It turned out to be a magical time for me—and my family. Anthony was so valued for computerizing the hospital I think they were more upset to see him leave than me. I loved practicing medicine the way I believe it should be practiced, with a real sense of community and trust between doctor and patient that is needed in big cities. Youd see your patients everywhere and they'd see you. I used to joke that I was forever treating yeast infections in Aisle 5 of the supermarket."

She came to realize that such closeness also could be harrowing, when her babysitters 23-year-old daughter almost bled out as Allen-Davis performed an emergency hysterectomy, anxiously waiting for blood to arrive by plane to the reservations primitive landing strip. Allen-Davis recounts the procedure and her patient fading in and out of consciousness—and the aftermath—as though it were months rather than years ago. While the outcome was successful, Allen-Davis is not likely to forget, the patient's six-week check-up, when the young woman recounted having seen her dead grandmothers and a white light as Allen-Davis fought to save her. Equally memorable, she says, was the way others working at the hospital joined forces. "A ward clerk I'd operated on the week before was running back and forth in her hospital gown between my babysitter and the operating room to keep her informed," she marvels.

While her 1992 move to Colorado meant medicine on a larger scale—especially after she joined KP in 1994—she thinks of patients in personal rather than merely clinical terms. "I'm not a fan of top-down medicine," she says. "You can't communicate enough or in enough different ways with patients. You have to be interested in their hearts and minds."

In her new role she'll be promoting her view broadly, working with KP's medical staff, community and government agencies to communicate her passion for patient safety and affordable health care for all. "When it comes to health care reform," she says, "we should always be thinking in terms of how a decision would be made if a patient were present. We need patients at legislative and political meetings." She describes the estimated 44,000 to 98,000 health care-error deaths in the United States annually as "simply unacceptable," and looks forward to developing more patient education and physician support programs. "My job is to tell a bedtime story, to make a complex subject clear," she says, "to translate the market to our medical group and us to the market."

To stay in touch with patients and colleagues and to keep her surgical skills honed, she's doing shift work about one day a week. "It was very difficult to say goodbye to my patients all day, everyday once my new job was announced," she admits. "But you never know what lies ahead. I'm happy to still be using my clinical and surgical skills."

Recently Allen-Davis participated in Leadership Denver, a program designed to foster civic leaders across a variety of disciplines, including government and the arts. "It was the coolest thing I've ever done," she says. Asked if politics might be in her future, she says such a career would be more likely for her government-major daughter, Courtney Davis '09. "She could run the world," says Allen- Davis, who speaks with equal pride of son Jonathan, a high school junior and Dartmouth hopeful. "I can't see myself back in Washington," she says. "I'm just happy with a job where I can make a difference. If you get clear what your goals are and find people willing to help, it's amazing what comes to you."

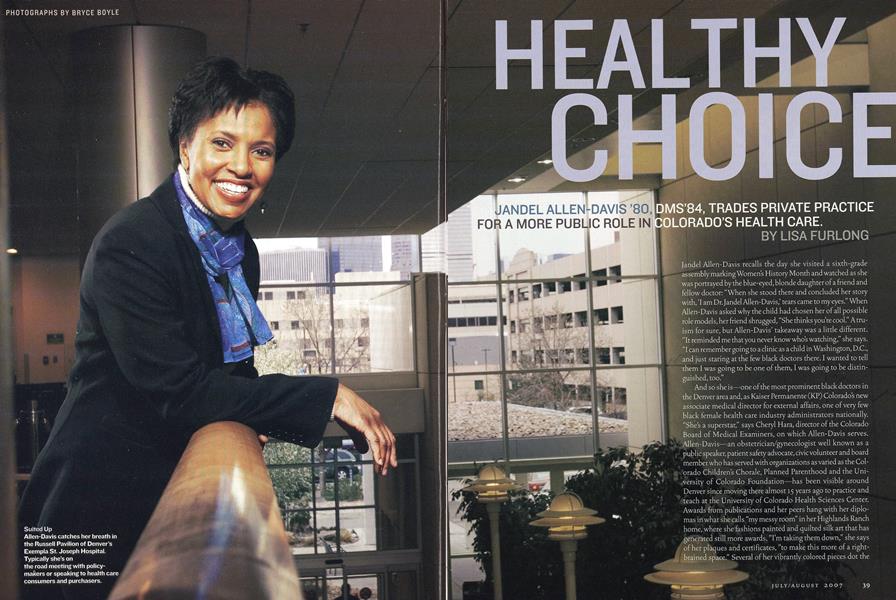

Suited Up Allen-Davis catches her breath in the Russell Pavilion of Denver's Exempla St. Joseph Hospital. Typically she's on the road meeting with policymakers or speaking to health care consumers and purchasers.

The Doctor is In Although Allen-Davis gave up most of her private practice to take on her new role, she still works a weekly shift in the hospital.

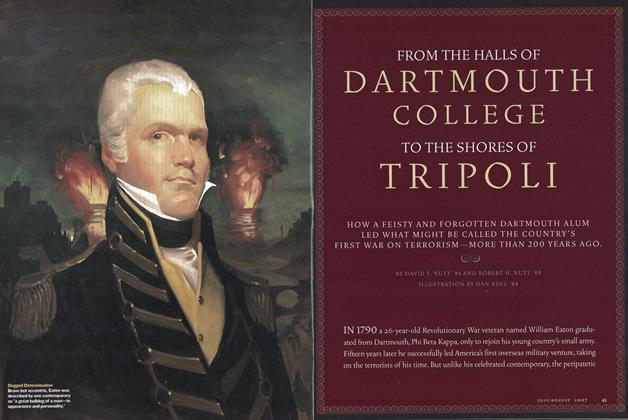

Dogged Determination Brave but eccentric, Eaton was described by one contemporary as "a great bulldog of a man—in appearance and personality."

"I'M NOT A FAN OF TOP-DOWN MEDICINE," ALLEN-DAVIS SAYS."YOU CANT COMMUNICATE ENOUGH OR IN ENOUGH DIFFERENT WAYSWITH PATIENTS. YOU HAVE TO BE INTERESTED IN THEIR HEARTS AND MINDS."

LISA FURLONG is senior editor of Dartmouth Alumni Magazine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER -

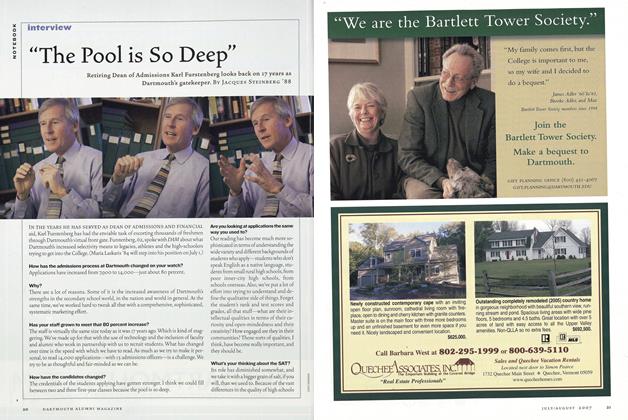

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July | August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88

LISA FURLONG

-

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationDavid Brown '76

Jul/Aug 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

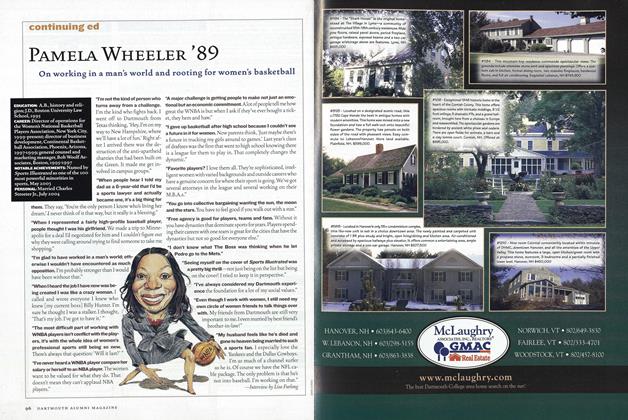

Continuing EdPamela Wheeler ’89

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

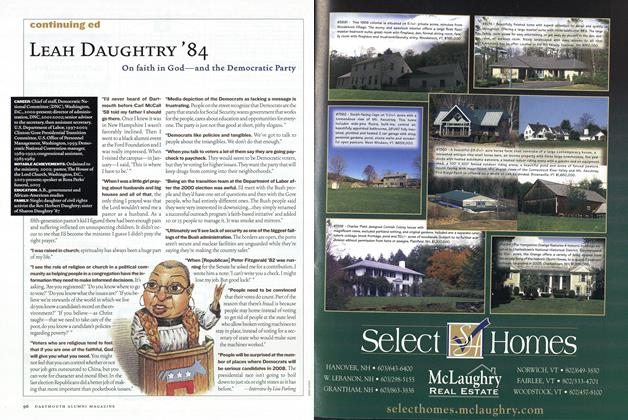

Continuing EdLeah Daughtry ’84

July/August 2006 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

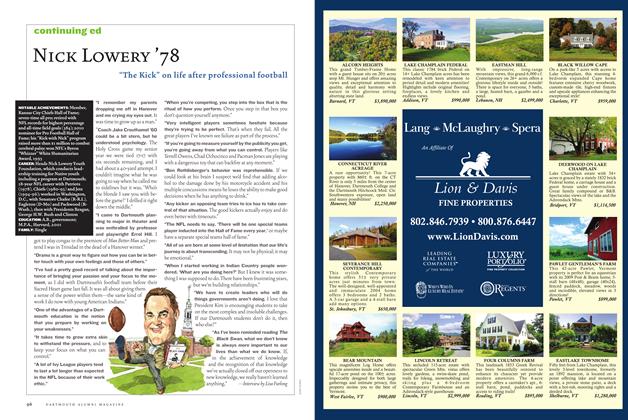

Continuing EdNick Lowery ’78

Jan/Feb 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

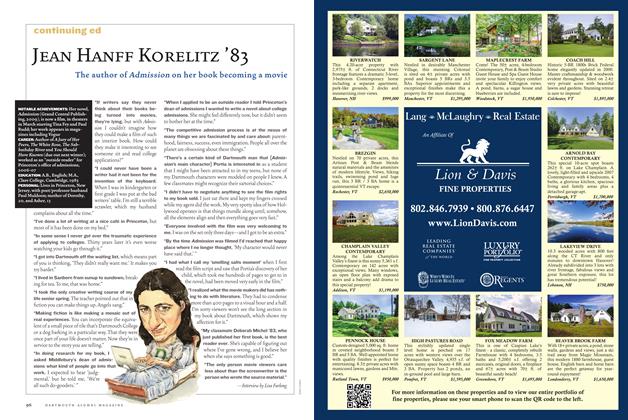

Continuing EdJean Hanff Korelitz ’83

Mar/Apr 2013 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationKevin Peter Hand '97

July/Aug 2013 By Lisa Furlong

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Plan

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO STOP HATING CLASSICAL MUSIC

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERICH KUNZEL JR. '57 -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

DECEMBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

OCTOBER 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

FEATURE

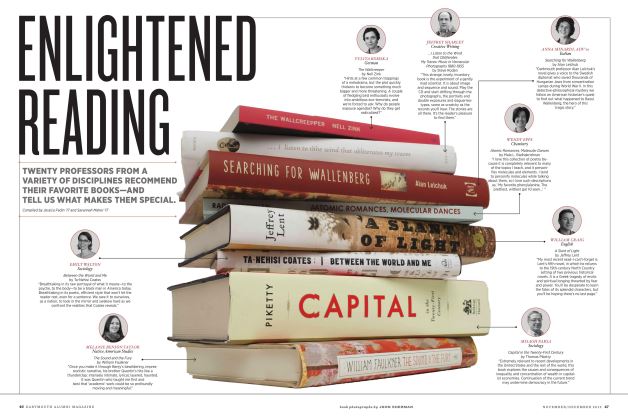

FEATUREEnlightened Reading

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By Jessica Fedin ’17 and Savannah Maher ’17 -

Feature

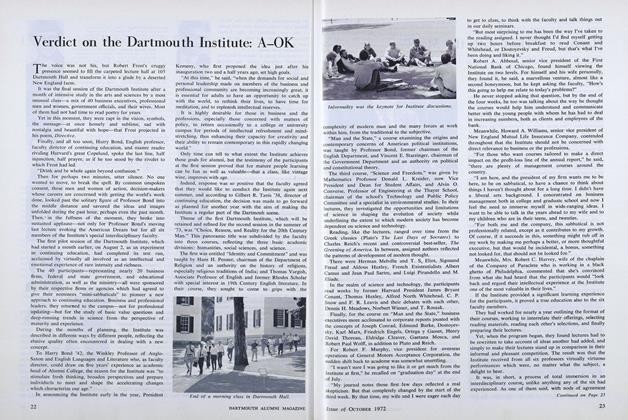

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40