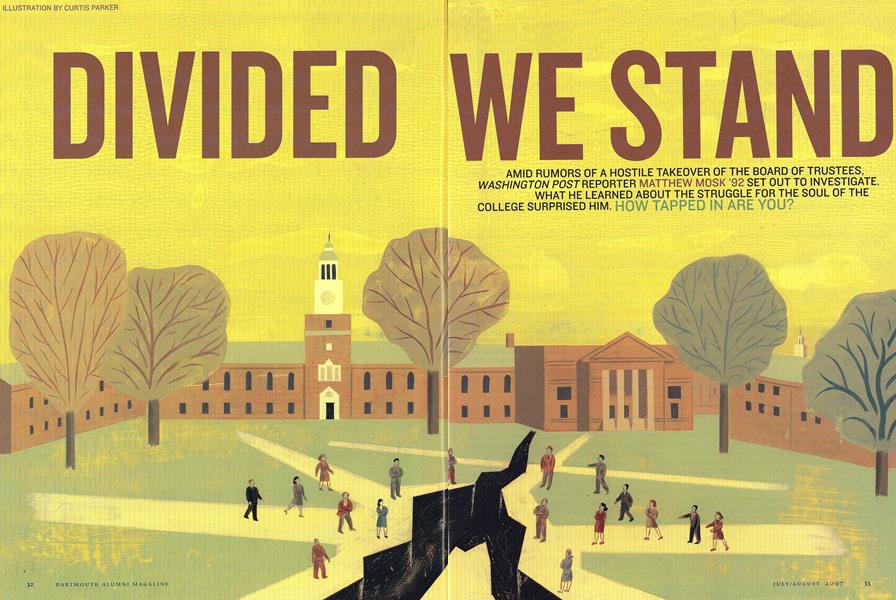

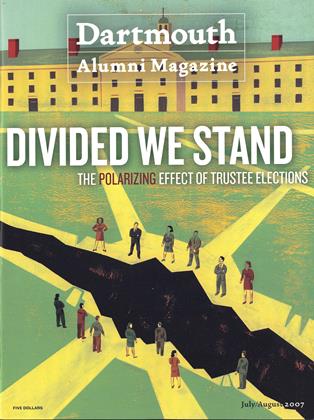

Divided We Stand

Amid rumors of a hostile takeover of the board of trustees, Washington Post reporter Matthew Mosk ’92 set out to investigate. What he learned about the struggle for the soul of the college surprised him.

July/August 2007 Matthew Mosk ’92Amid rumors of a hostile takeover of the board of trustees, Washington Post reporter Matthew Mosk ’92 set out to investigate. What he learned about the struggle for the soul of the college surprised him.

July/August 2007 Matthew Mosk ’92AMID RUMORS OF A HOSTILE TAKEOVER OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, WASHINGTON POST REPORTER MATTHEW MOSK '92 SET OUT TO INVESTIGATE. WHAT HE LEARNED ABOUT THE STRUGGLE FOR THE SOUL OF THE COLLEGE SURPRISED HIM.

IT WAS ONE OF THOSE GREAT MORNINGS IN HANOVER.

Alums and parents and students milled about the lobby of the Hanover Inn, some with steaming cups of coffee, others heading out with skis slung over their shoulders. Light streamed in as members of the Dartmouth board of trustees clutched file folders marked "Confidential," and trudged past the front desk to a second-floor conference room, where the fireplace was lit. Their plan for this quick March meeting was to run through budget matters in the morning, gobble down a quick lunch, then cross the snow-draped Green for an afternoon meeting in Baker Library.

I had arrived in town the previous day, intent on learning more about the alumni constitution, a topic that still seemed fuzzy to me despite the many e-mails and letters urging me to take sides and vote. My assignment, initially, had been to wade into the murky questions surrounding alumni governance at Dartmouth. What role should the alumni be playing in setting campus policies? What rights should we have to exert our collective influence if the College suddenly contemplated eliminating the Greek system or becoming a major research university or reviving the Indian symbol?

Early spring seemed an opportune time to delve into these questions. The bruising battle over the constitution had just ended, and lots of folks were taking stock. President James Wright was in the midst of drafting a new mission statement for the College. The Alumni Council's leaders were doing the same for the council. Three outside petition candidates had challenged their way into seats on Dartmouth's board of trustees, and a fierce election fight for a fourth seat was under way.

Something strange happened, though, almost from the moment I started asking people about alumni governance. As I made initial calls to members of the Alumni Council, class officers and people in the College administration, each seemed suspicious about the agitation going on within the ranks of alumni.

Some sensed that a more profound plotline had begun to take shape—that each of these skirmishes over trustee seats and the confusing fight over the alumni constitution may actually have been part of an ongoing war for the soul of the College being waged just out of view. What would happen, I was asked more than once, if a clique of alums, each of whom appeared to be motivated by the same ideological concerns, continued to snap up additional trustee seats? Would they eventually hold enough votes to control the entire board? Were dissidents using the alumni elections process to mount some sort of takeover of Dartmouth College?

This kind of conspiratorial talk didn't carry much weight with me. It still seemed outlandish when I headed to Hanover to catch up with people most deeply involved in the direct oversight of the College. Outlandish, that is, until I spotted board of trustees chairman William Neukom '64 striding purposefully toward Baker Tower that first afternoon. Neukom is an imposing man—tall and dapper with a trademark bow tie and a sweep of silver hair. For a time he sat on the Forbes list of wealthiest Americans. He had overseen the team of lawyers devoted to protecting intellectual property rights for the powerful software giant Microsoft. He was polite when I introduced myself but seemed reluctant to talk.

I decided to give him a taste of what I'd been hearing. "Listen," I asked, almost sheepishly, "do you think there's an effort afoot to mount a hostile takeover of the board of trustees?" Here I fully expected a denial. Some sort of polished, lawyerly brushoff that would squelch this rumor before it spread any further. But after a long pause, Neukom slowed his gait for just a moment. "It's complicated," he said.

I SHOULD ADMIT right up front, I'm not the most involved of our 67,700 alumni. I try to write a small check every year, though sometimes I forget. I'm occasionally in demand to speak with students by virtue of my job as a Washington Post reporter. I help advise the juniors who run The Dartmouth and try to meet with freshmen who come to the nations capital as part of a civic skills program run by Rockefeller Center. But I've never voted in a trustee election. I almost always delete the campaign e-mails and toss the leaflets without reading them. During last fall's battle over the alumni constitution I felt no compulsion to get involved. Frankly, I found the whole thing confounding.

But then I set out to learn what all the fuss was about. And so, with many questions in mind, I drove north to Baltimore one winter morning before work to interview Martha Beattie '76, who is president of the Alumni Council. Even though she was in the midst of moving from Baltimore to Vermont, she agreed to sit down over coffee at her house to talk about the future.

Beattie is part of a quintessential Dartmouth family—daughter, wife and mother of alums. When I asked her what role she thought alumni should be playing in governing Dartmouth, she set down her mug of coffee and sank back in her chair. "The one thing that is so sad about alumni governance is that it's become a political game," she began. "Especially when it comes to trustee elections. You would just hope that choosing the stewardship of the College for generations to come could be completely free of politics. But it really has become 50 political."

Beattie explained that the politics consuming Dartmouth stemmed from its standing as one of just a few schools of its caliber to allow the alumni to elect trustees. Eight of the 18 board members must stand for a vote of the entire alumni body before their names are sent to the other board members for final approval. It's a ritual that has been in place since 1891, when the College was facing financial troubles and needed more support from its graduates.

While this system has had its moments through the years, the inception of todays crisis over trustee elections appears to date back only 27 years. That's when John F. Steel III '54, a urologic surgeon from LaJolla, California, mounted the first successful petition bid onto the board. Steel told his fellow alums he had been offended when his daughter Kimberly '83 received a letter of reprimand from the College for wearing clothes displaying the recently retired Indian symbol. His concerns struck a nerve with those who feared the College was losing touch with important traditions and with others who were worried it was displaying politically correct tendencies they believed could impinge on the kind of free speech and expression that helps enliven a campus.

Steel's successful bid, which coincided with the launch of TheDartmouth Review, touched off a tumultuous period in which politically conservative alums began to clash openly with administrators on a range of subjects. When the late historian Wilcomb E. Washburn '48 launched a second petition candidacy in 1989, discontent was at full boil. His bid fell short by 4,000 votes, but not before both sides had spent more than $100,000on campaign mailings. Conservative alumni, using the Review as their mouthpiece, turned up the volume on complaints that the school had become overrun by liberals and had traded in a traditional curriculum for less rigorous courses such as women's studies.

In 2003 the Alumni Association responded with a series of changes to the voting rules that officers said were intended to broaden the field of trustee candidates and eliminate the need for petition challenges. After a short period of quiet, petition candidates resumed their push for seats on the board. In quick succession T.J. Rodgers '70 in 2004 and Peter Robinson '79 and Todd Zywicki '88 in 2005 captured spots. In May Stephen Smith '88 gained another trustee position. The elections were contentious—and increasingly sophisticated. Petition candidates had Web sites that championed issues seemingly impossible to oppose: free speech, improved athletics, smaller classes. When Rodgers ran he refused to be labeled a "conservative" candidate, calling himself a libertarian. When I later asked Rodgers why he sought his seat, he said he had three main issues: "Issue one, two and three are the preservation of Dartmouth College, comma, the best undergraduate college in the world, period." Tough to argue with that.

Others, including Beattie, suspected the petition trsutees had a wider agenda. Why, she wondered, were conservative bloggers and the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal getting behind these petition campaigns? Why was a conservative group in Washington founded by Lynn Cheney and Sen. Joe Lieberman in 1995, the American Council for Trus tees and Alumni (ACTA), involved? To whom was Rodgers referring when, after he was elected, he told DAM, "I view my role as a change agent, representing the alumni who elected me."

Jim Adler '60, another Alumni Council member, said Beatties suspicions are shared by many. There has been a prevailing sense among those on the council that these challenges are being orchestrated and that they have the backing of powerful conservative interests, he said. "Is this something that Todd Zywicki and Peter Robinson and now Stephen Smith did on their own? Adler asked. "I don't think so. It's too professional."

Wondering about this, I sent an e-mail to Joe Asch '79, a longtime critic of the administration and frequent op-ed contributor to The D, to see if he had a different perspective. He does—he thinks all this talk of conspiracies is hogwash.

"I think that many people have independently come to the conclusion that all is really not well in Hanover, and that the College is not open to constructive criticism—and, in fact, is engaged in an ongoing whitewash campaign of its own," he wrote.

He pointed specifically to the slick brochures that had been landing in most alumni mailboxes during the winter, trumpeting the Colleges successes. He believed the efforts weren't working. "Little by little our engaged alums (aided and abetted by the power of communication that the Internet gives to individuals) are talking to each other," he wrote. "Their messages of alarm are falling on fertile ground."

I asked Asch where he thought all of this would go. What do the disgruntled alumni want? He replied that they want change, and he's quite clear where he expects change to start. "I think many alums believe Dartmouth needs a new president, one who can set a better course for the school."

In a follow-up e-mail Asch elaborated on why new leadership should be sought. "Virtually the entire upper echelon of the College administration has been here for decades," he wrote from Hanover, citing Wright, provost Barry Scherr, acting dean of the College Dan Nelson '75, dean of the faculty Carol Folt, athletic director Josie Harper and dean of student life Holly Sateia. "I think alumni strongly sense that the current administration is top-heavy with members of the insiders' club and therefore slow to move in any direction. There are few if any new ideas coming to Hanover from the outside."

Beattie seemed truly disheartened as she talked about the roiling emotions within the alumni body. "All this distrust has developed," she told me. "I keep thinking, 'We have to fix it.' " Just how to fix it, though, remains a puzzle.

ON THE EVE of the March trustee meeting I dropped by Robinson Hall to see what was brewing in the offices of The Dartmouth. The papers new editor, Phil Salinger 'OB, was huddled with a reporter who was in the midst of reporting what they thought would be a big story. The D was investigating a new group on campus, the Phrygian Society, which is said to have selected its ancient name to represent liberation from servitude and a fight against despotism. The D had obtained e-mails in which members of this secret, all-male group wrote they "have recently decided to take matters into our own hands and actively preserve the Dartmouth way of life." Phrygians were asking alumni to donate to the organization in order "to preserve the Dartmouth that you love, a Dartmouth that is being obliterated by overzealous administrators in the name of political correctness." The newspaper had a photo of the group as well—it showed three rows of members, most in slacks, blue blazers and ties. In the front row, just right of center, was petition trustee Zywicki.

I met Zywicki the following day at the front desk of the Hanover Inn. He had just flown in from Virginia, where he teaches law at George Mason University. The first thing that struck me was how young he looked—hardly the ruddy, balding trustee I expected. With his tousled head of brown hair, wire-rimmed spectacles and impish grin, he looked even younger than his 40 years. He is, he told me, the youngest man ever to hold a trustee seat, and he confided that when he won his petition bid he felt "a little like the dog who caught the car."

As we headed to the Canoe Club for lunch, he seemed warm and willing to talk about his motives for joining the board. He told me his discontent with the College, to the extent he had any, was rooted in the arrival on campus during his time as a student of President James Freedman, who served the College from 1987 to 1998. Freedman's evident distaste for fraternities, his seeming disinterest in athletics and his strong ties to Harvard didn't sit well with Zywicki, much as it hadn't with the College's more hidebound alumni. "It was the whole university instead of college; the political correctness apparatus, the war on the fraternities, the undermining of the athletic program, the emphasis on the creative loner instead of the well-rounded Dartmouth student.That was the whole direction the College was headed," Zywicki said. Those concerns served as the coal that powered the petition movement straight through the 1980s and 1990s and that, to varying degrees, continues to this day.

I told Zywicki about the conversation I had with Adler, the former president of the class of 19 60, who had told me he had his own reservations about Freedman—"I didn't exactly score a 1600 on the SAT myself," Adler had laughed, recounting his own desire to see Dartmouth remain an incubator for well-rounded human beings. But Adler's sense was that those concerns seemed out of all proportion with what was actually occurring on campus. He wondered if there wasn't a group of alums that wanted to see the College preserved in amber. Zywicki answered by recalling a conversation with Stephen Smith, who described sitting at the National Press Club in Washington in 1999 as a College administrator announced plans for the student life initiative, a recently concluded program designed to overhaul student social options and diminish the influence of Greek houses. "He described the stunned disbelief, how people were just shocked by the social engineering that was rolled up in this," Zywicki said. "I don't know how such a misguided sort of approach could be made. It was not a case where we agree to disagree. Everybody saw that as crazy."

and to the administration. I recalled another instance where a College proposal so inflamed the alumni that the council gave a response similar to a sharp tug on a dogs leash—the November 2002 decision by athletic director Harper to eliminate the swim team. I suggested to Zywicki, as Adler had to me, that the Alumni Council stepped in to urge trustees to rethink the goals of the initiative; that this might be an example of how the Alumni Council has been successful in its role of relaying alumni concerns to the trustees

Harper was then facing a $400,000 budget shortfall and considered taking a little bit from every sport. But she felt that would mean a slow demise for Dartmouth athletics. So she settled on a plan to cut the one sport with the least appeal and the most expensive facilities. She announced she was cutting varsity swimming and diving. "I expected a very, very harsh reaction from alumni, kids, families," she says. "That's what we got. There's a passion and a history here. Everyone was screaming and yelling." When the Alumni Council intervened, President Wright brought everyone to the table and asked them to find a way to save swimming. "They were given the challenge of raising about $2 million in six months," Harper recalls. The alumni came through, collecting more than $2 million in pledges by late January 2003.

Zywicki agreed the alumni rose to the occasion. But he said he is concerned that decisions at Dartmouth ultimately are "driven by squeaky wheels" and the administration is continuing to push a "Freedman agenda." That, he said, is why he and others fought so hard to defeat the changes to the alumni constitution and, in his view, protect a petition process that helps ensure he and others have a voice on the board of trustees. "In other schools the only way alumni can make their voices heard when they're upset is by withholding contributions," Zywicki said. "That doesn't happen at Dartmouth because people have the chance to participate in trustee elections. They can say, 'Even though I don't expect I'm going to win, I feel at least I have a voice.' "

Zywicki rejects the notion that this discontent is wrapped up in politics or ideology. "I don't know what I've said or done that suggests I'm doing anything conservative," he says. "I don't think for any of the petition candidates this is about politics. That's a brand our critics have tried to put on us. I think the alumni have seen through that. We've tried to make very fact-based, reasonable arguments and let Dartmouth people decide."

As I walked away from the lunch I had no doubt Zywicki had tapped into unrest among alumni about the way Dartmouth is being run. What I couldn't tell was whether his efforts were part of an organized, concerted movement to take over the board of trustees. As much as he rejected that assertion, I wondered what he was doing meeting with a secret student group whose stated aim was to attack the College administration. Later, when The Dartmouth story on the group was published, I saw the reporter had asked Zywicki about his meetings with the Phrygians and he had refused to comment. I later called Zywicki to see if he would share his reasons for gathering with the group, and his answer to me was the same.

"I met with them in a private meeting, so I'm not going to go into any detail with you about who they are or what their goals might be," he said.

DARTMOUTH ALUMNI LOVE their College. That goes all the way back to Daniel Webster, class of 1801. But every romance has its tests. One of those moments came last fall in the wake of campus unrest with Josie Harper's letter of apology in The D for having invited the "Fighting Sioux" of the University of North Dakota to play in Dartmouth's annual Ledyard hockey tournament. The outcry that followed was predictable, though it might surprise some, as it did me, just how angry this episode made some alums. When I dropped by Harper's office to talk about it, she showed me a thick blue binder filled with the letters she had received. She had them divided under the headings, "Rude," "Offensive," "Critical and Thoughtful," "Support." Let's just say the "support" section was pretty thin, while the other sections included vulgar letters, thick with profanity. This made me wonder just how turbulent the alumni mood had become, so I sought an interview with the man most responsible for having his hand on the pulse of the alumni body, David Spalding '76. Two years ago Dartmouth lured Spalding from Wall Street to head its alumni relations office. Although he had not been previously involved in campus politics and anticipated his job would be one of "friend raising," he is a man who knows a thing or two about hostile takeovers. When he arrived in Hanover he walked smack into the battle over the alumni constitution.

Spalding viewed the effort to revise the constitution in simple terms: It would bring efficiency to an alumni structure split between an Alumni Council, which serves as a conduit for sending information between the alumni and the College, and the Alumni Association, which carries out the election of trustee candidates. The proposed changes had been years in the drafting.

Somehow, though, the constitution vote became freighted with deeper meaning. Rodgers, Robinson and Zywicki announced their opposition to the revised constitution, saying it would place additional burdens on future petition candidates. The Dartmouth Review,The Wall Street Journal editorial page and the Washington group ACTA, whose national council includes William Tell '56 and, until recently, judge Laurence Silberman '57, all sensed a plot to stifle the trustee election process and began advocating for the defeat of the proposed constitution. "If Dartmouth wants to become known for corrupt administrative practices and failure to respect democratic decision-making processes when it comes to its own alumni, it's doing a wonderful job," ACTA announced in a press release.

Spalding said the Colleges official position was that it would not take sides in the constitution vote, but it's not difficult to tell what he hoped would happen. He launched an effort to get as many people to submit a ballot as possible. From a statistical standpoint this made perfect sense to him, he told me in March as I sat down in his office on the second floor of the Blunt Alumni Center.

In several surveys conducted by alumni relations, Spalding had found that 8 5 percent of alumni described themselves as "satisfied" or "very satisfied" with the direction of the College. Presumably, he thought, more votes would make the new constitution's passage more likely. That's not what happened. Spalding said the constitution "was a complicated document. There were a number of changes proposed, and lots of moving parts. All of it was open to interpretation. Motives were called into question. I'm sure some or all of those things turned off a number of people."

I wondered whether he thought the constitution's downfall was a sign that a group of alums, maybe even conservative alums, had created better-organized, better-financed campaign machinery than those of any mainstream alumni groups. I also wondered if the College administration viewed the organization as a long-term threat.

"If you talk to any of [the constitution's opponents], they deny they were organized," Spalding replied. "So it's hard for me to comment on the level of organization of the group. Certainly you can see things that appear to be orchestrated in things they do, but they certainly claim they're not organized." I asked him to elaborate. He pointed to an incident described on the Web site of San Diego Padres CEO Sandy Alderson '69, an Alumni Council-nominated trustee candidate who lost in the latest election.

Alderson's site described his petition candidate opponent Smith as "sought out and selected by a handful of agenda-driven alumni with control of a mailing list, access to considerable funding and supported by a politically motivated organization," he wrote. "I know this to be true, because I personally met with most of the five or six alumni involved when they considered supporting my candidacy. That proved impossible for them and me even though their views on some issues are not fundamentally different from mine. The problem for me is that, for most in this group, their loyalty to a political ideology seemed stronger than their loyalty to the College." When questioned about this claim, Alderson identified the alumni with whom he met at their invitation as Steel, Rodgers, Robinson and Zywicki, the latter by phone. Alderson said that although he had already agreed to run as an Alumni Council- nominated candidate, he nonetheless was asked if he would consider running as a petitioner.

Steel, with whom Alderson met first and at length, "told me he was one of five or six votes when it came to supporting a petition candidate," Alderson said. "It was pretty clear to me in my conversations with him and the others that the way someone voted on the constitution was the determining factor in gaining their support." In a telephone interview with DAW, Steel confirmed this. "I think Sandy is an outstanding individual. I was surprised that as a lawyer he had voted for a document, one opposed by 51 percent of alumni, that would limit petition candidates in the future," Steel said.

"The reason they opposed the new constitution is that they understand how the current system can be manipulated ," Alderson told DAM. Smith vigorously disputed Alderson's public allegations, posting a "Declaration of Independence" on his trustee campaign Web site. He said he received donations from far and wide, not from a single, ideological group.

"I am, in fact, a truly independent candidate," he wrote.' No one and no group-liberal, conservative or otherwise-is controlling or bank-rolling my campaign. I wasn't 'recruited' by anyone to run for trustee. The decision to run and the positions I've taken are mine and mine alone, and I alone am responsible for my mailings and Web site. I am running to make certain that alumni have a viable alternative to the candidates hand-picked by the Alumni Council's nominating committee—a commitee that, according to one of the nominated candidates, has shied away from picking anyone deemed 'independentminded.' "

Spalding told me that, Smith's protests notwithstanding, "It certainly sounds like there is a group out there trying to pick candidates. These candidates are not arising spontaneously."

So why have they succeeded in winning three successive seats if 85 percent of alumni are happy with the way things are going at Dartmouth? Spalding said in some respects it's a matter of math. Under the current approval voting system, which allows voters to indicate their support of multiple candidates, the three Alumni Council nominees split the votes of their supporters, while supporters of the petitioners vote only for the one, sometimes two, petition candidates.

BACK IN THE LOBBY of the Hanover Inn I spotted a spark plug of a man lugging a heavy briefcase. It was T.J. Rodgers, the man some were describing as the architect of a hostile takeover.

Rodgers comes across as blunt—some might say imperious—and has the military bearing of a field general. He is in all ways a CEO. He heads Cypress Semiconductor, a Silicon Valley high-tech company. But he was more than willing to address my questions about this so-called plot to gain control of the College. "It's been called the radical cabal," he grinned as we sat down. 'And I guess, therefore, if there is a leader of the radical cabal, that leader has to be me!"

If he was the leader of an alumni cabal, as he jokingly called it, he was not about to acknowledge it. To the contrary, he told me forcefully: "There isn't an organized effort."

His next comments, however, seem to leave enough room for doubt. "I've heard the 'hostile takeover' phrase," he said. "If you look at it, it doesn't make sense at face value. Alumni trustees are only half the board. In the very best case of a takeover the best you could do is get 50 percent of the votes. The fact is, it would take you eight or 10 years to do that, and there's never been a period in the College's history where there's been a sustained effort for eight or 10 years to take over the board."

I suggest to him that by gaining 50 percent of the seats (not counting the two seats held by the College president and the New Hampshire governor), the petition members would then be in a position to control the selection of the remaining membersthose who are not elected. I tell him he strikes me as a patient man, one who might be willing to sustain an effort for a decade or more. If that is his plan, I asked, why not discuss it openly? He told me why.

"The reason we win elections is we don't talk about stuff like that," he said. "We talk about Dartmouth College. [Opponents of the petition candidates] keep talking about things that don't matter. Politics, takeovers, things like that. It's all bunk. What the alumni care about is making sure the Dartmouth they loved is the Dartmouth they will continue to love. They're concerned that it may be drifting." For the next 15 minutes Rodgers was true to this approach. He talked about free speech on campus, about academic excellence, about Big Green sports.

Not another word about a takeover.

BACK IN WASHINGTON I dialed Neukoms number at the Preston Gates & Ellis law firm in Seattle. He answered his own phone. I asked him about unrest within the alumni ranks and again prodded him on the question of the petition movement and what it could mean for the long-term health of the College. He told me he believes he, President Wright and the other trustees have identified the root of the problem. It is not that Dartmouth has swerved in the direction of Harvard or tried to mold creative loners instead of well-rounded men and women. He rejects the idea that the College is bent on destroying the fraternities or disinterested in its athletic prowess. The problem, as he sees it, is that there are alumni who actually believe all of those things to be true.

He put it like this: "The heck of it is that we just have not done as good a job as we could have describing [what's happening on campus]. What we're learning is, we've left a vacuum. It's easier for people to become curious or even skeptical and believe a rumor or an innuendo about what might be going on at Dartmouth. So we just have got to improve the understanding our alums have of what's going on at Dartmouth. The fact is it's a lot of very good stuff."

He told me he's so intent on doing a better job of spreading the word that he's now got the College hunting for a new vice president of public relations. He's planning to devote more resources (read: money) to "telling the Dartmouth story." This is a task for both the generals and the soldiers. Neukom said he has asked his fellow trustees to serve as "ambassadors." He has tasked Spalding to "come to work every day thinking about how can we get useful information to our alums about Dartmouth and how can we get the thoughts and feelings of the alums back into the College."

This helps explain why President Wright announced the College would be "truth-squadding" claims made during the recent trustee elections to make sure no one was misinforming the alumni while trying to capture votes. "If someone says the faculty is shrinking, we will set that straight," Neukom said during our phone conversation, which occurred before voting had started. "If someone says classes are getting bigger, we will provide information to show that's not the case. We will not sit back and let allegations go untested by the facts."

Will a public relations blitz be enough to persuade disaffected alumni that the board of trustees and the administration, as it is currently composed, can shepherd the College into the future? Can Neukom, or anyone else, assure the 85 percent of alumni who say they are happy with the direction of the College that the more vocal 15 percent, who say they aren't happy, won't wrest away control of the board?

Neukom acknowledged that while the trustee election process is an important element in the way Dartmouth has been governed for more than a century, it is technically true the trustees could choose to reject a nominee who's won the popular vote. Under the Colleges bylaws the trustees are the final authority on who joins their ranks.

Rodgers told me when we met that such a move by the trustees would be "a nuclear event." I asked Neukom if there is any scenario under which the trustees might exert that option—say, if the petition candidates continued to win elections and snapped up six or seven or eight seats on the board? "I don't think there's any algorithm here," he replied. "We've had two experiences, two years in a row. We are watching." With Smith's victory it is now three "experiences" in three years.

I thought I needed to put this question to President Wright. He agreed to answer it in a phone interview in late March. From the outset it was clear Wright had heard plenty about the swirling concern about a trustee takeover. "I try not to spend my time obsessing about this," he told me. "But there's no doubt there are forces at play here that you just can't minimize."

Wright said he believes the petition drives are being financed and orchestrated, but he's not sure by whom. Wright also said he could not envision a scenario in which the board would override a trustee election. "It would be quite a step if they were to do that. If they really had reservations about the way a campaign was conducted they would be capable of doing that. But I'm not sure they would want to impose an additional filter following an election," he said. "Something quite substantial would have to be there for them not to take the elected nominee."

Wright seemed uneasy talking about this. I asked him if he was worried about what all these contested elections were doing to the College. If he's worried at all, he replied, it's because Dartmouth will continue to be misunderstood, not only by the segment of alumni who believe the campus is too liberal but also by a public at large that may be convinced that Dartmouth remains a bastion of political conservatism.

When he said this I couldn't help but recall the time immediately after graduation when I was first seeking a job in journalism. In interviews editors would see Dartmouth on my resume and would ask about the only issue they had seen in headlines about the College during those years, the public antics of the Review. I don't know where the trustee battles will lead, but I sense both sides recognize the risk to Dartmouth's reputation if these battles persist.

"A [DAM] reporter last fall asked me why it is that Dartmouth has a reputation of a conservative place that's always at war with itself," Wright recalled. "You find reference to shanties or The Dartmouth Review or Animal House. Very few stories about Dartmouth don't weave those pieces into it. And yet, it's a far richer place than any of these artifacts would suggest."

TODAY'S CRISIS OVER TRUSTEE ELECTIONS APPEARS TO DATE BACK ONLY 27 YEARS, WHEN JOHN STEEL '54 MOUNTED THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL PETITION BID ONTO THE BOARD. STEEL HAD BEEN OFFENDED WHEN HIS DAUGHTER RECEIVED A REPRIMAND FROM THE COLLEGE FOR WEARING CLOTHES DISPLAYING THE RECENTLY RETIRED INDIAN SYMBOL.

ZYWICKI SAID HE IS CONCERNED THAT DECISIONS AT DARTMOUTH UTIMATELY ARE "DRIVEN BY SQUEAKY WHEELS," AND THAT THE ADMINISTRATION IS CONTINUING TO PUSH A "FREEDMAN AGENDA." THAT IS WHY HE AND OTHERS FOUGHT SO HARD TO DEFEAT THE CHANGES TO THE ALUMNI CONSTITUTION.

MATTHEW MOSK covers national politics for The Washington Post He lives in Maryland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

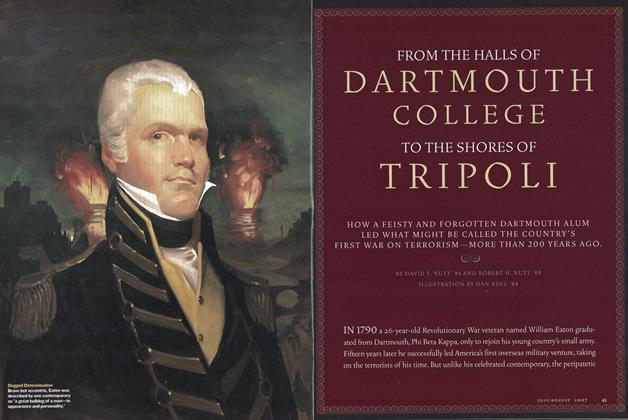

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

Feature

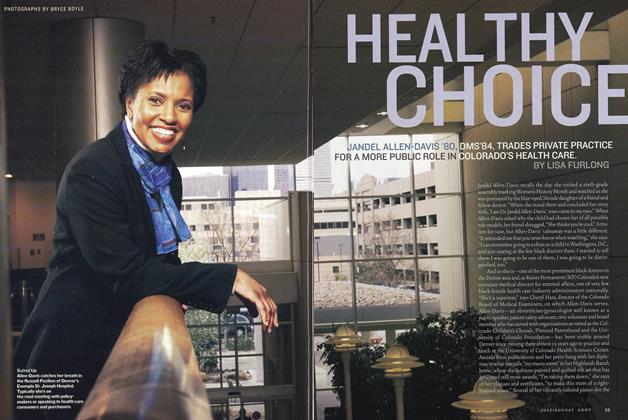

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July | August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88

Matthew Mosk ’92

-

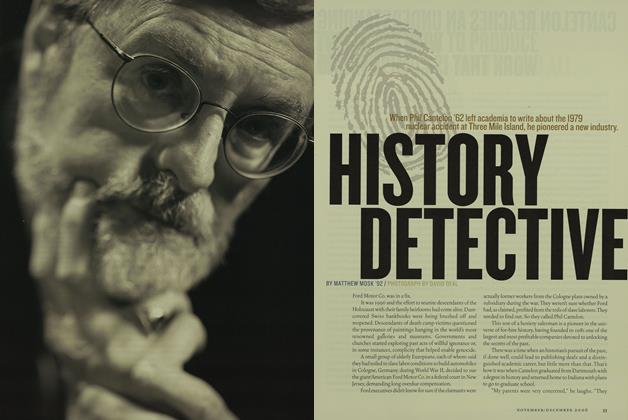

Feature

FeatureHistory Detective

Nov/Dec 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

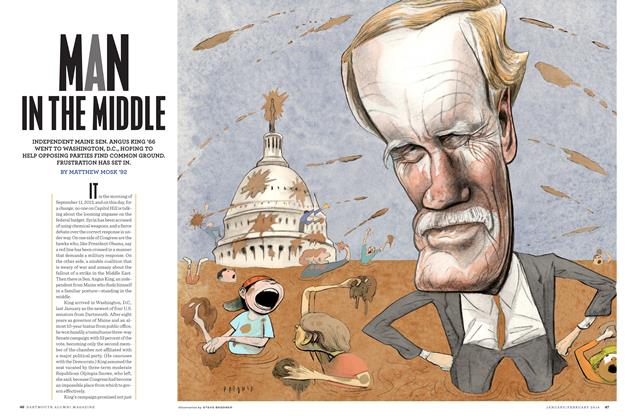

FeatureMan in the Middle

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

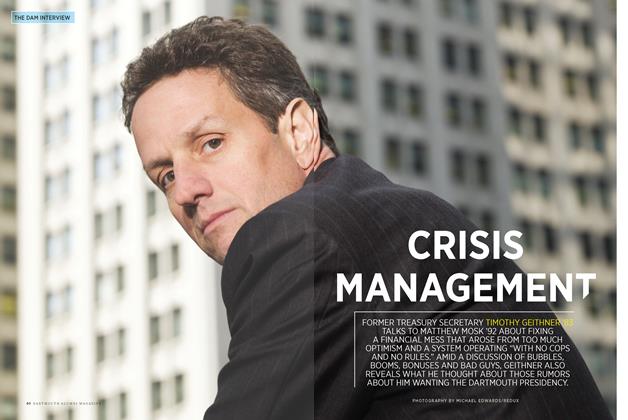

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWCrisis Management

July | August 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

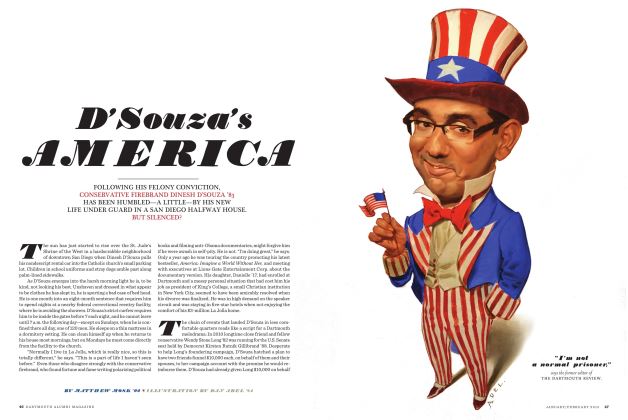

Feature

FeatureD’Souza’s America

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Fixer

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

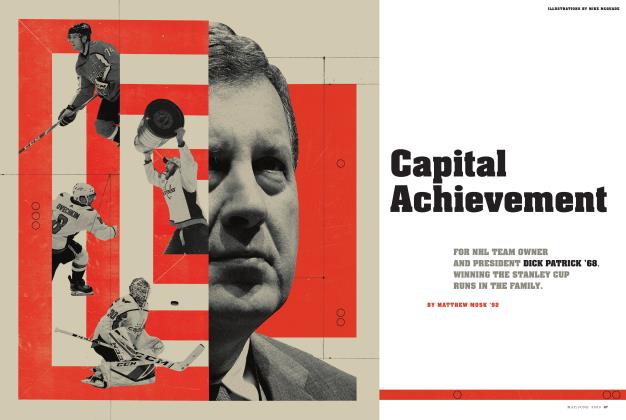

Sports

SportsCapital Achievement

MAY | JUNE 2020 By Matthew Mosk ’92