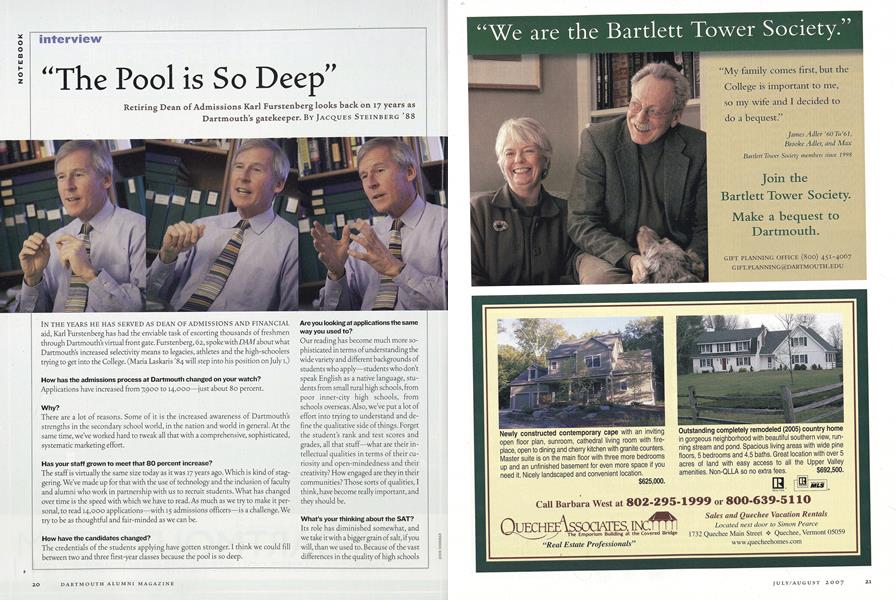

“The Pool is So Deep”

Retiring Dean of Admissions Karl Furstenberg looks back on 17 years as Dartmouth’s gatekeeper.

July/August 2007 Jacques Steinberg ’88Retiring Dean of Admissions Karl Furstenberg looks back on 17 years as Dartmouth’s gatekeeper.

July/August 2007 Jacques Steinberg ’88Retiring Dean of Admissions Karl Furstenberg looks back on 17 years as Dartmouth's gatekeeper.

IN THE YEARS HE HAS SERVED AS DEAN OF ADMISSIONS AND FINANCIAL aid, Karl "Furstenberg has had the enviable task of escorting thousands of freshmen through Dartmouth's virtual front gate. Furstenberg, 62, spoke with DAW about what Dartmouth's increased selectivity means to legacies, athletes and the high-schoolers trying to get into the College. (Maria Laskaris '84 will step into his position on July 1.)

How has the admissions process at Dartmouth changed on your watch?

Applications have increased from 7,900 to 14,000—just about 80 percent.

Why?

There are a lot of reasons. Some of it is the increased awareness of Dartmouth's strengths in the secondary school world, in the nation and world in general. At the same time, we've worked hard to tweak all that with a comprehensive, sophisticated, systematic marketing effort.

Has your staff grown to meet that 80 percent increase?

The staff is virtually the same size today as it was 17 years ago. Which is kind of staggering. We've made up for that with the use of technology and the inclusion of faculty and alumni who work in partnership with us to recruit students. What has changed over time is the speed with which we have to read. As much as we try to make it personal, to read 14,000 applications—with 15 admissions officers—is a challenge. We try to be as thoughtful and fair-minded as we can be.

How have the candidates changed?

The credentials of the students applying have gotten stronger. I think we could fill between two and three first-year classes because the pool is so deep.

Are you looking at applications the sameway you used to?

Our reading has become much more sophisticated in terms of understanding the wide variety and different backgrounds of students who apply—students who don't speak English as a native language, students from small rural high schools, from poor inner-city high schools, from schools overseas. Also, we've put a lot of effort into trying to understand and define the qualitative side of things. Forget the student's rank and test scores and grades, all that stuff—what are their intellectual qualities in terms of their curiosity and open-mindedness and their creativity? How engaged are they in their communities? Those sorts of qualities, I think, have become really important, and they should be.

What's your thinking about the SAT?

Its role has diminished somewhat, and we take it with a bigger grain of salt, if you will, than we used to. Because of the vast differences in the quality of high schools across the country and because of the test preparation business, which creates an equity issue in making decisions, we look at the test as a rough indicator. But we also look at the test paired with a very careful evaluation of the transcript, the rigor of the courses a student has taken and the quality of the performance.

Why not make the SAT optional for Dartmouth applicants?

It's an important tool. We need all the information we can possibly get.

Has your thinking on legacy admissionschanged?

The percentage of a class that is comprised of legacies is still about the same as it was about 17 years ago—in the 10 to 11 percent range. The approach we've always taken is that the legacy connection to Dartmouth is important to the institution. That connection is a plus on a student's application. It continues to be a tie-breaker, if you will. That seems to me to be appropriate. With so many well-qualified candidates, and with legacy having sort of an extra plus in the application, it does lead to a rate of admissions of legacies that is a little bit more than double the overall rate of admission. Because Dartmouth calls on its alumni a great deal, I think part of the bargain is we're going to take a close look at their children should they apply to Dartmouth.

A few years back your letter to the president of Swarthmore applauding theschool for dropping varsity footballwound up having some reverberationson the Dartmouth campus. Any secondthoughts?

I wrote to reassure the president there, who is a friend, that the decision he had made seemed to me to be a good one for Swarthmore. That letter obviously did command a lot of attention. In retrospect, certainly I regret it. But I would separate the view I was expressing in the context of Swarthmore to what goes on here. I think the Ivy League has it just about right, in terms of intercollegiate athletics. Nonetheless, you wrote, "You are exactly right in asserting that football programs represent a sacrifice to the academic quality and diversity of entering first-year classes. This is particularly true at highly selective institutions that aspire to academic excellence. My experience at both Wesleyan and Dartmouth is consistent with what you have observed at Swarthmore." How do you reconcile that sentiment with the role of athletics in the admissions process at Dartmouth?

We work very hard to try to attract students who are serious academically and come from a variety of different backgrounds. If you remember back to 2001 and the Bill Bowen book, The Game of Life, he pointed out in pretty stark terms that the students who are being admitted primarily for athletic reasons tend to be a less diverse group and somewhat off the mark academically compared to other students being admitted. Since that time, Dartmouth and the Ivy League in general—the presidents—have really ratcheted up the academic standards. As the academic profile of our first-year classes has increased, it means the profile of students playing collegiate sports has also increased.

How do you feel about the pressure theadmissions process puts on prospectivestudents?

The concern for me is that kids are being forced to grow up too soon, too fast. To make choices that may not he following their heart as much as following what they think they're supposed to do to get into college. The most selective colleges need to think about what they can do to tamp down the pressure on students. We're kind of a mixed mind about it. We're all recruiting very extensively to attract the strongest applicant pools we can find so we have the strongest first-year classes. At the same time, you really raise this question: Does Dartmouth, does Yale, does Princeton really need more applicants? My goodness, only close to one out of 10 is getting in. In some ways I think we would all benefit from, if you will, a SALT treaty—Strategic Admissions Limitation Talks—where maybe we can be a little more restrained in our recruiting efforts.

But you can't do that unilaterally, partlybecause a lot of alumni, among otherconstituents, wouldn't tolerate our going it alone on this issue, right?

Precisely. A lot of what happens is that there's this round of stories in the media every spring—"Are you up or are you down?" I think it would be okay to be down if everybody else was down. But if you're down and other places are up, that's worrisome. There's institutional pride and self-interest in wanting to get our share of the best kids. So we're out there hustling like everybody else.

What else might highly selective colleges do that might serve to ease theanxiety applicants are feeling?

One thing I have very mixed feelings about is the whole movement toward Internet applications and these standardized applications. Most of us now accept the common application as our exclusive application. So there is one application you can use to apply to any one of a couple hundred different colleges. All the Ivies accept the common application. If colleges went back to having individual applications, students would think twice about applying to 12 or 15 different colleges. They'd be more judicious about the schools they apply to. That would probably improve the admissions yield as well.

If President Jim Wright said, "Karl, it'sentirely up to you: Do we get rid of earlydecision, or at least binding early decision?" what would you do?

I would keep early decision as we have it now. That has been my position all along, for two principal reasons. One, I think it's valuable for the student and valuable for the institution for them to sort of make this first-choice match, to simplify the admissions process. If the student is clear that Dartmouth is his or her first choice, why not indicate that to us, make a commitment, and we go from there? The other reason I like an early-admission program, and I'm thinking more broadly now, is that in this age of multiple applications it actually helps reduce the number of multiple applications. It tends to work against trophy collecting on the part of kids, which really does happen.

What proportion of the class of 2011 wasadmitted early?

About 35 percent. That contrasts with a couple of the other Ivies that have been doing 50 percent, which I think is crazy.

What will you miss most about the job?

This is a great job. Sure, there are a lot of pressures and a lot of people looking over your shoulder. At the same time, what a great opportunity to represent a fabulous institution with a need-blind admissions program, where we can provide millions and millions of dollars in financial aid to everybody we want to admit. You know the old show The Millionaire! It's like that. You go around the country to find all these great kids, armed with $14 million of financial aid to make it possible for them to come here.

JACQUES STEINBERG is the author of The Gatekeepers: Inside the Admissions Process of a Premier College He covers television and the mediafor The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

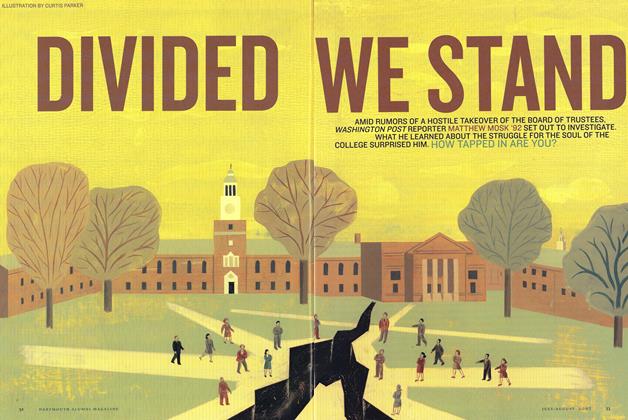

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

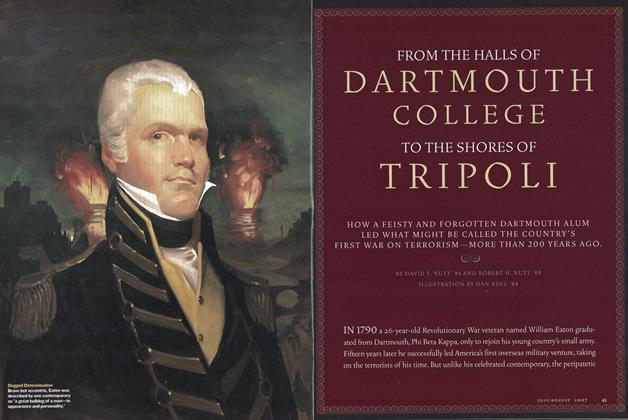

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

Feature

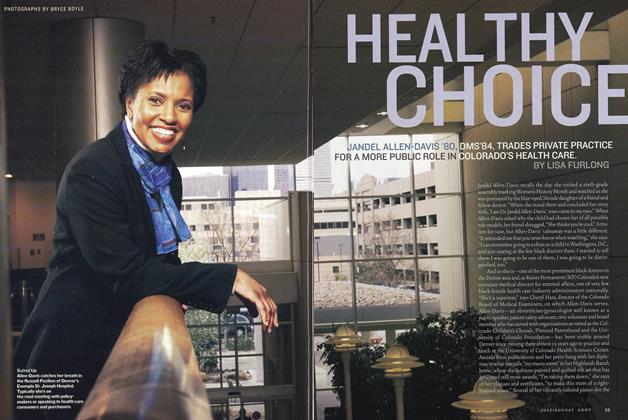

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

Jacques Steinberg ’88

-

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

MAY 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

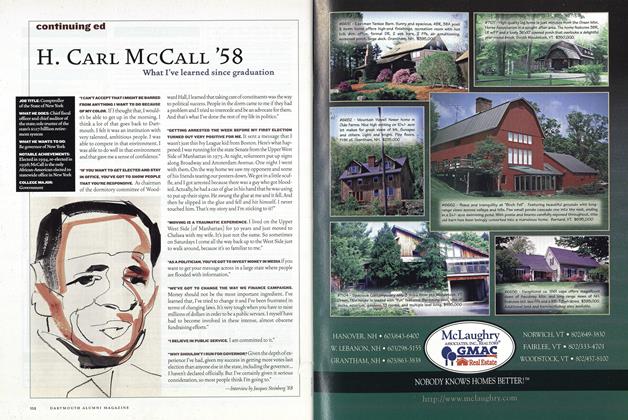

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdH. Carl McCall ’58

Sept/Oct 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdJohn Hagelin ’76

Mar/Apr 2001 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

Nov/Dec 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

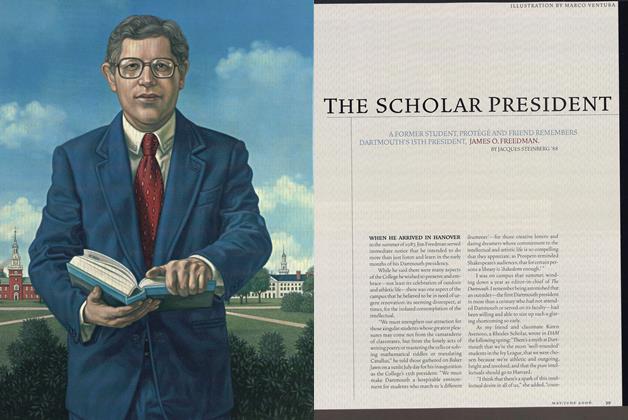

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May/June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

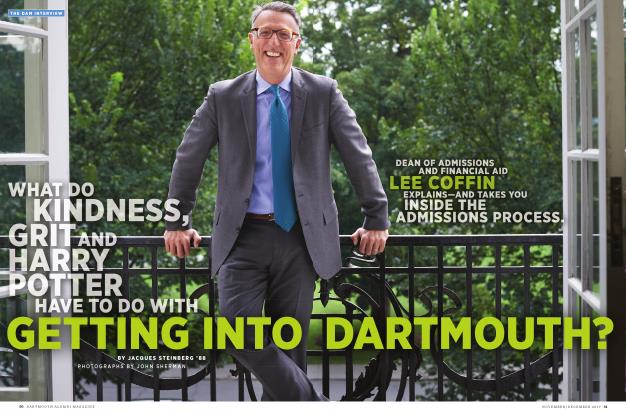

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWLee Coffin

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88

Interviews

-

Interview

Interview“Now We Have a Platform for Discussion”

MARCH 2000 -

Interview

InterviewA Fan's Notes

Sept/Oct 2007 -

Interview

Interview“Look Globally”

Mar/Apr 2006 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Interview

InterviewMany Happy Returns

Nov/Dec 2000 By Robert James Bauer '82 -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Sarah Clark '11 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“We Did What Was Best”

Nov/Dec 2007 By Sean Plottner