Robert Rules!

Think you’ve heard it all when it comes to Robert Frost, class of 1896? Here are three ways in which the poet is still making news.

July/August 2007Think you’ve heard it all when it comes to Robert Frost, class of 1896? Here are three ways in which the poet is still making news.

July/August 2007Think you've heard it all when it comes to Robert Frost, class of 1896? Here are three ways in which the poet is still making news.

FROST'S FLOWERY PROSE REVEALS HE KNEW HIS NATURE.

By the time Peter White was 5, he could recite several poems:by Frost. And not just "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," either. "I'd mastered some of the more obscure ones, too, like 'Bereft,' " says White, whose mother, an English teacher, often recited poetry to him.

Now White, who earned a Ph.D. in biology from Dartmouth in 1976, works as a plant ecologist at the University of North Carolina, where he also oversees the university's botanical garden. In a unique talk he's delivered about a dozen times at the garden during the past six years, Frost and biology merge, with wonderful result.

During the talk, titled "Turn the Poet Out of Doors: A Natural History of Robert Frost," White quotes from some 58 Frost poems and explains the learning that went into them. "Frost was a real student of natural history," says White. "He clearly took plains to identify things, from lichen and moss to species of birds."

"The Rose Family," for instance, is a short poem that contains in its apparently romantic lines a complete scientific taxonomy of the rose family, which Frost, unlike most, understood included the apple, pear and plum. In another poem, "Come In," Frost writes about the woodthrush, a bird with a beautiful song that lives in deep woods. He seems well aware of the specific sort of forest it needed to thrive. And "Rose Poeonias," says White, grew out of Frost s constant search for orchids in the woods of New England, one of which resulted in the discovery of a species not known to grow so far north.

Telling the story, White repeats a few lines with the surety of a man who has been doing it since he was 5:

We raised a simple prayer Before we left the spot, That in the general mowing That place might be forgot; Or if not all so favoured, Obtain such grace of hours That none should mow the grass there While so confused with flowers.

Bryant Urstadt '91

2 FROST'S WORK HAS BEEN SET TO MUSIC, (POSSIBLY TO HIS CHAGRIN.)

"Some say the world will end in fire, Some say in ice." So wrote Frost more than 80 years ago in a poem about the imminent destruction of civilization. The world is still here, and so is the Dartmouth Handel Society (above), which has turned to Frosts poetry to celebrate its bicentennial. The oldest collegiate town-gown choir in the United States performed a new choral cantata based upon eight early Frost poems for its anniversary gala conceit in May at the Hopkins Center. The 50-minute cantata—titled "Fire and Ice" after Frosts poem—was written by Andrea Clearfield, an award-winning Philadelphia-based composer.

The commissioning committee of the Handel Society wanted the work to reflect the history of Dartmouth, for which Frosts poetry lent itself perfectly. Clearfield says she liked to work with Frost's poetry because he expresses universal themes in a local setting. She spent time at Dartmouth, visited the landmarks of Frosts life and made long hikes in Frost's footsteps to immerse herself in the landscapes that inspired the poet.

Careful listeners may have recognized an additional local reference in the music: the melody of the Baker Tower carillon. The melody was often veiled, appearing in fragments or hidden within other melodies, but a full melody appeared in the second movement.

The themes of the cantata are duality and conflict, which are the essence of music and poetry, according to Clearfield. It consists of four movements, the first of which is a rendering of the poem "To the Thawing Wind." The remaining movements interpret the poems "October," "Fragmentary Blue," "Going for Water," "The Demiurges Laugh," "Fire and Ice," "Stars" and "Pan with Us."

"I love the darkness under the surface in these poems," says Clearfield.

Whether Frost would have loved this musical interpretation of his work is unclear. In a 1962 talk at Yale he said: "There are two kinds of music, the music of poetry and the music of music, and they aren't the same thing."

Judith Hertog

3. FROST'S PERSONAL NOTEBOOKS ARE LOVELY, DARK AND DEEP.

"Does Tolstoy ask us to believe the poor are more virtuous than the rich?" That's one of many questions posed by Frost to his Amherst students during the 1923- 1924 academic year. Many similarly "deep thought" questions—and thousands of jottings (some comprehensible, some not)—are found in the recently published and annotated edition of The Robert FrostNotebooks (Belknap Press). Most reviews of the hefty volume mention how it shows the poets mind at work, but excerpts from two notebooks (all but a handful of the 48 originals belong to Dartmouth; one is shown above) reveal Frost in an unexpected way. Despite his growing fame, he was an engaging instructor.

"He was capable of holding forth for hours," says Notebooks editor Robert Faggen, a professor of literature at Claremont McKenna College. The questions Frost recorded in his notebooks "reveal his preoccupation to bring up points to challenge students," says Faggen. "They were designed to provoke and stimulate."

Frost made idiosyncratic choices for class readings. In addition to Tolstoy, for example, Frost assigned George Borrows Lavengro and selected works by Homer and Kipling. A common thread among his book selections: literature that poses questions about critical judgment. Frost also asked students to read books of their own choosing. As one of Frosts notes to himself reads, "Let them tell me about a book not assigned."

The notebooks also doubled as Frosts gradebooks. One notebook records student names, grades and a list of the books each student read and wrote about. Despite appearances, Frost "is really making decisions" with these notes, says Faggen. "He's not a distracted poet."

Instead of acting flippant, Frost, who won the first of four Pulitzers toward the end of that school year, "kept track of everything," says Faggen. "And there was no slacking off with his own writing."

Frost graded by the numbers, and his class was not an easy "A." His Amherst notebook records only two 100s—and one 65—out of a class of 42.

Lee Michaelides

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

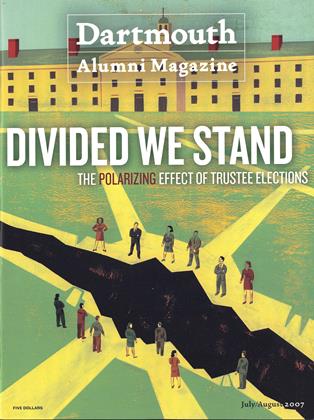

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

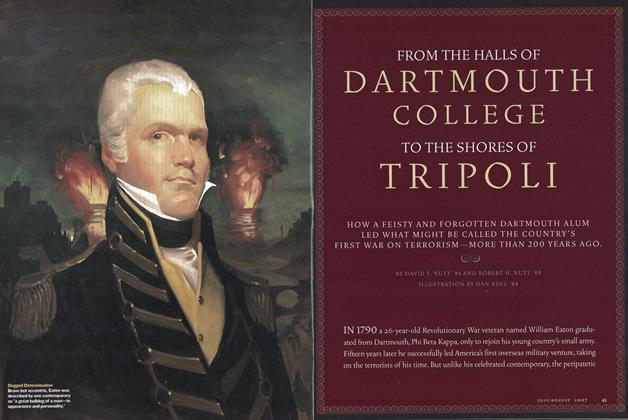

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

Feature

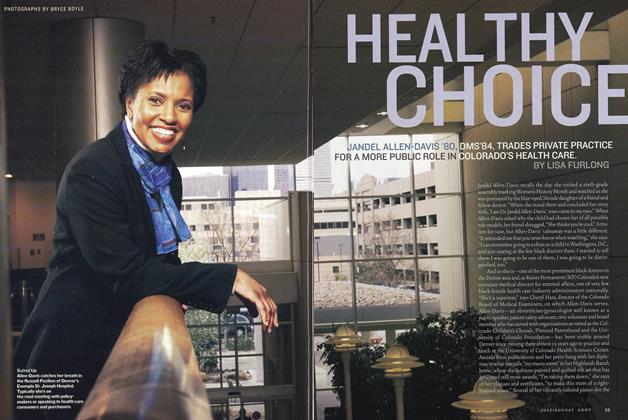

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER