Storied Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, an old voice from the wilderness, looms large during this International Polar Year.

OF THE SEVERAL THOUSAND PHOTOGRAPHS IN the collection of the Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson housed in Rauner Library, the most telling shows Stef—as he was widely known—lecturing on the Green. The image gives some idea of why he was beloved at Dartmouth, where he taught for the last decade of his life. The students are obviously engrossed by Stefansson's demonstration of how to build an Inuit snowhouse; one has even forgotten to wear a coat in the middle of winter. Here, as in other images of Stefansson at the College, he cuts the figure of a dedicated teacher whose capacious knowledge of the Arctic is matched only by his gifts as a storyteller.

For a man who wrote "adventure is a sign of incompetence," Stefansson proved a remarkably brave explorer, adept ethnographer and a tireless advocate for the Arctic and its native inhabitants. He came to Dartmouth in 1947 widely regarded as one of the worlds greatest explorers, having met numerous heads of state, graced the covers of popular magazines such as Life and delivered countless lectures on his notion of "the friendly Arctic." His collection of manuscripts and photographs, which he donated to the College, remains one of the largest compendia of polar materials in the world.

This year Stefansson is in the spotlight with the 2007-2008 International Polar Year (IPY), a series of conferences, research initiatives and exhibitions that focuses on the state of the polar regions, whose political and environmental future will have wide-ranging implications as global warming becomes an increasingly pressing issue. The evolution of Arctic studies into a holistic field encompassing environmental science, cultural anthropology and geopolitical considerations would have been impossible without Stefansson's pioneering ability to recognize that the Arctic was not merely an obstacle course but a place unique in its ability to enrich our understanding of humanity's relationship to the natural world. "Stefansson's discoveries were of an intellectual nature as well as a matter of geopolitics," says Niels Einarsson, who heads the Stefansson Arctic Institute, a polar research center in Iceland. "He opened the eyes of his audience to the cultual and economic riches of the Arctic."

Sixty-seven countries will play host to portions of the IPY, which began last March with Iceland's foreign minister, Valgerdur Sverrisdottir, opening an exhibition about Stefansson at the North Atlantic House in Copenhagen.

Stefansson was raised on the grassy plains of North Dakota, his upbringing steeped in the culture of his parents' native Iceland. After a lackluster academic career that included a year at the Harvard Divinity School, he joined an Arctic expedition as an anthropologist in 1906, yearning for what he would term "the poetry of deeds." The expedition achieved little, but stoked the Nordic fascination that was about to consume his life.

There would always be a romantic aspect to his ventures into the north. "He wanted to be a poet—the tender part of him," says his wife of 30 years, Evelyn Stefansson Nef, now 94. His earnestness, however, was checked by organizational weakness and barely concealed scorn for researchers who did not share his grand vision of the Arctic. Nor was he free of the love of publicity that sometimes drove explorers to foolhardy feats and erroneous conclusions. Coming upon a small tribe of blue-eyed, blond natives in the northern reaches of the Canadian Arctic, he pronounced these the mythical "Blond Eskimos" who, according to legend, were the long-lost descendants of Greenland's Viking settlers. The media pounced upon his discovery, even if Stefansson ultimately acknowledged its weak factual underpinnings.

On a second Arctic journey in 1913 his disdain for planning proved fatal, when one of his ships was crushed by ice, half its men ultimately perishing on a deserted island. Stefansson continued his exploration, despite calls to return home, only deepening the view of him as a self- promoter who sorely lacked leadership skills. "He's still a little controversial," notes Gisli Palsson, author of TravelingPassions: The Hidden Life of Vilhjalmur Stefansson. "Some people discount him as a media man. He has that image of someone who's just in this for personal fame and headlines."

Despite these shortcomings Stefansson used his broad public stature to argue that the Arctic demanded widespread attention and that its people had much to teach about sustainable living. "His mission was to take the fear out of the Arctic and convince people that it was a place like any other," says Nef, who became an advocate for polar research in her own right.

Stefansson never returned to the Arctic after that ill-fated second expedition, devoting himself largely to an abiding love of literature. He authored several dozen volumes, from discourses on breeding caribou to a 20,000-page Arctic encyclopedia, and collected thousands more. By the 1940s his residence in New York City contained "books and not much else," according to Nef; having filled three apartments, his library needed a new home.

Dartmouth, where Stefansson had previously lectured, provided a chance to instill younger generations with knowledge of the Arctic. In 1951, four years after he was appointed Arctic consultant at the College, he and Evelyn decided to make Hanover their permanent home, the ever-expanding library in tow. Stefansson was "extremely well received" at the College, says Philip Cronenwett, the retired special collections librarian of Baker Library, who has worked extensively with Stefansson's manuscripts. "Stef saw the opportunities to really grow a program of polar studies," and the volumes he contributed now constitute what Cronenwett confidently calls "the most important Arctic history collection in the world."

Stefansson lectured extensively at the College and as the image of him on the Green shows, he captivated students. During the 1950s he helped start the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory for the Army in Hanover, promoted the Inuit diet of meat and fish as a healthful alternative to Americas reliance on starch-based foods, planned northern routes for Pan American Airways and used every public opportunity to highlight the natural and human resources of the Arctic. (He died in 1962.)

"The Arctic is like the canary in a coal mine. When things start to go wrong up in the northern areas, the impact spreads over the surface of the earth," observes Kenneth Yalowitz, whose leadership of the Colleges Dickey Center has been responsible for the renewed interest in Arctic studies on campus. Yalowitz and others credit Stefansson and his wife with initiating a program of Arctic studies that has had repercussions far beyond Hanover.

"In the Arctic science community we are by now used to good things from Dartmouth, which seems to be a place breeding intellectually sturdy, innovative and progressive ways of cooperating on complex issues," says Einarsson of the Stefansson Institute.

A sign of that cooperation is the rock sculpture that now faces the Green from the lawn of McNutt Hall. Known as an inuksuk, the formation is a "wayfinder" that marks the progression of a journey for the Inuit. Stefansson, always in search of roads not taken or questions unansweered, surely would have been proud of this homage to his beloved Arctic.

The Iceman Stefanssontransformed the Green intoa classroom, teaching Inuitconstruction techniques.

The Polar Year at Dartmouth The College dedicated its IPY activities to the centennial of Stefansson's first Arctic expedition by convening the Arctic Science Summit Week last March. More than 200 scientists, policymakers and indigenous representatives came to Hanover to discuss responses to the burgeoning global warming crisis. To complement the summit, last January the Hood Museum of Art organized "Thin Ice: Inuit Traditions within a Changing Environment," an exhibition that celebrated Inuit art and culture while warning of impending threats such as melting ice caps and thawing permafrost. The Dartmouth Northern Conference and Lectures series brought to campus speakers such as Inuit political activist Mary Simon, who discussed indigenous rights in a May speech, while the Collis Center showcased "Visions of the Poles," an exhibition of student artwork on the Arctic. The IPY activities showcase an "interdisciplinary set of approaches to understand complicated programs" -such as how indigenous cultures have responded to climate change, says professor Ross Virginia, head of the Dickey Center's Instituted of Arctic Studies, which promotes the study and understanding of high-latitude regions. These are the concerns Stefansson shared. "We're recognizing that a lot of his work, a lot of his writing about the North and the way he saw the North changing is coming to be," notes' Virginia.

ALEXANDER NAZARYAN is a writer andteacher working on a novel about Russian immigrantsin New York. He lives in Brooklyn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

SPORTS

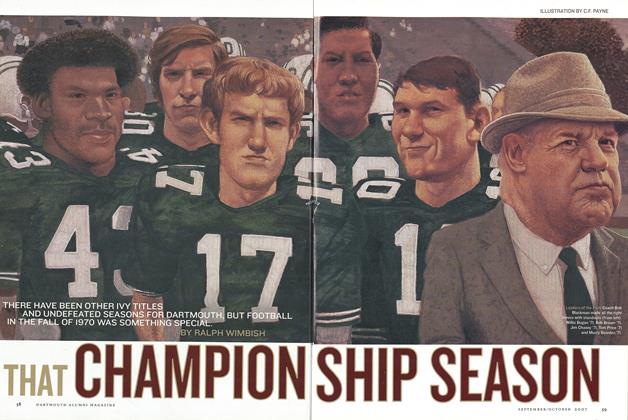

SPORTSThat Championship Season

September | October 2007 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

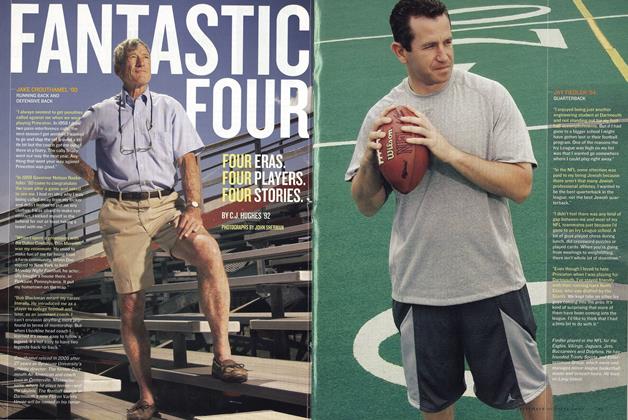

FeatureFantastic Four

September | October 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

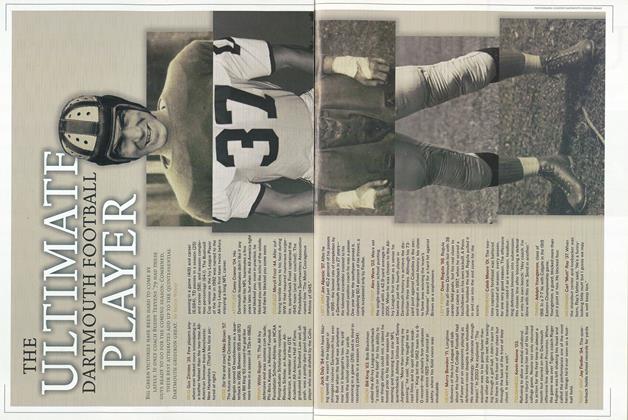

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

September | October 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Feature

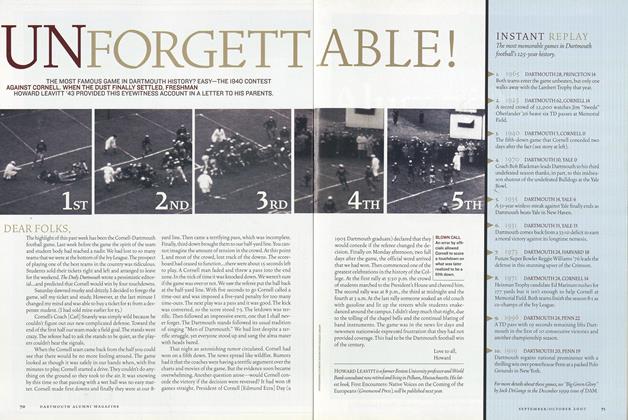

FeatureUnforgettable!

September | October 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

SPORTS

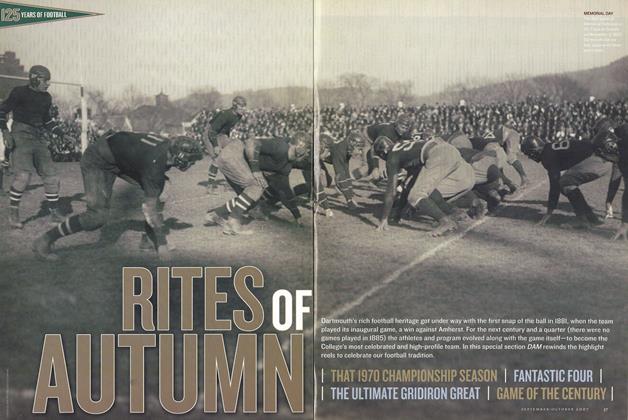

SPORTSRITES OF AUTUMN

September | October 2007 By Courtesy Dartmouth College Library -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74

Article

-

Article

ArticleMovies for Rental

April 1934 -

Article

ArticleHeads Irvington House

March 1952 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1961 By DAVE SCHWANTES '62 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

November 1944 By G. W. Woodworth, H. L. Duncombe Jr. -

Article

ArticleJerry Crowley

FEBRUARY 1930 By H. F. W