Boston Legal

Using a rough-and-tumble lawyer as a recurring character, David Hosp ’90 has made it as an author without abandoning his day job.

Mar/Apr 2009 Maria KaragianisUsing a rough-and-tumble lawyer as a recurring character, David Hosp ’90 has made it as an author without abandoning his day job.

Mar/Apr 2009 Maria KaragianisUsing a rough-and-tumble lawyer as a recurring character, David Hosp '90 has made it as an author without abandoning his day job.

DAVID HOSP SEEMS TOO WELL AD- justed to be a writer—or a lawyer for that matter. Yet at 39, he's successful as both.

In a windowed club 38 floors above Boston, the genial intellectual property lawyer and author of three successful legal thrillers gestures toward the harbor below, explaining how his literary career began. "I commute to Boston by ferry," Hosp explains, noting that he travels from the South Shore suburb of Cohasset, where he lives with his wife of seven years and their two young children, to his law firm Goodwin Procter LLP in the financial district. "Everyone is always looking to take the fast ferry," Hosp explains, "but I'm always looking to take the slow ferry."

The reason is that Hosp wants time to write. In fact, his literary career was literally born in 2003 on the slow boat across Boston Harbor, where twice a day, five days a week, the newly married young father found the peace and quiet necessary to start writing Dark Harbor by longhand on a yellow legal pad. It was published in 2005 and followed a year later by Betrayed. His third book, Innocence, is based on a real death row exoneration case Hosp was involved with as a volunteer for the nonprofit Innocence Project, founded by lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufield to revisit questionable convictions using DNA evidence.

All three books feature an ensemble of quirky, colorful and well-drawn characters. The lead character in all of them, Scott Finn, at first glance, could not be more different than his creator. While Hosp is the product of a self-described happy childhood in Westchester County and an Ivy League education, Finn is an orphan and former juvenile-delinquent-in-training from a hardscrabble Boston neighborhood. The fictional Finn is a lawyer though, who in the first book is practicing at a major Boston firm. By book three he has jumped ship to open his own small law office in nearby Charlestown. Other recurring characters include Finns on-again, off-again love interest, the beauteous Boston police detective Linda Flaherty; Finn's grizzled ex-cop sidekick, the cynical Tom Kozlowski; and Kozlowski s eventual love interest, the sexy and "gutter-mouthed Lissa," as she is described in Kirkus Reviews.

Hosp is currently working on a fourth book, Among Thieves, a fictional account of the search for paintings stolen in 1990 from Bostons Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

He is either coy or keeping his ego firmly in check when talking about exactly how well he's done as a novelist. "Honestly, I don't actually know how many copies have been sold but the books have been published in six or seven languages, including Japanese, German, French, Spanish, Polish and Danish," he says. 'And I get a kick out of it when friends contact me, like one did recently, to say he saw huge billboards for Innocence in the London Underground." (His publisher, Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Books, also declines to provide sales figures.)

Suffice it to say that compared to most young novelists, or most old novelists for that matter, Hosp has been extremely successful. And one gets the sense, even after only a brief meeting with him, that despite the laid-back demeanor he is extremely ambitious, focused and just beginning what will be a successful literary career. Like other lawyer-writers who came before him, including Scott Turow and John Grisham, Hosp writes thrillers focused on crime, punishment, murder, justice and injustice. The novels, all around 450 pages, are mostly set in and around Boston and recreate a shifting world of good and evil, with plenty of sex and graphic violence to keep readers turning the pages.

When asked which is easier to write, sex or violence, he laughs—and reddens. "Violence," he says. Blue eyed, sandy haired with a hip and un-lawyerly stubble of beard, he looks more mature than he appears to be on the back cover of his first book.

Perhaps because he already has a well-paying day job and doesn't have to depend totally on writing to support himself and his family, "I have fun with it," he says of his writing. "I don't get stressed. I just write, and the characters emerge and start to act and move the story forward." Hosp says he writes the books on the ferry, then types and rewrites the drafts later.

The younger of two sons, Hosp was born in Manhattan and then moved to Rye, New York, where he attended prep school at Rye Country Day.

He says he is close to his father, a successful Manhattan advertising executive, and to his mother, a lawyer. His parents have a beach house in Rhode Island that he and his family visit frequently and where he spent a year following his college graduation building houses before attending law school at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Hosp embarked on what seems like his sole rebellious act—going to Dartmouth—at 18, an unexpected choice for the youngest son in a family of Brown men. A history major, he never took an English or writing course but he was entranced by anything related to drama. He was active in productions at the Hop, working behind the scenes for The MasterBuilder and in a small role in Devil Mas. Although he was recruited for lacrosse, injuries kept him from playing. Instead he helped JV coach Bobby Clark. Belatedly he joined Theta Delta Chi.

"Writing was one of my great loves," he says, but as it had been during his childhood, it was strictly for his own enjoyment. "It was a hobby and I didn't really tell anybody about it or show anybody what I was doing," he says. "I outlined plays and wrote stories for myself."

While in law school Hosp says he wrote many "bad songs" and started a band called Slow Children at Play, which played gigs in nightclubs around D.C. He also had fun, he says, as the founder of a literary magazine for law students who could contribute their fiction and poetry and get together to drink beer on Thursday nights.

Although he spent a year in New York City after law school, at Winthrop, Stimson, Putnam and Roberts, Hosp says he felt "claustrophobic" there. "It didn't help I was stabbed in the chest outside a bar," he says. "Having someone try to kill you tends to make you reevaluate things in general." He wanted to work in New England at a firm where he could pursue his interest in intellectual property law. As a lifelong Red Sox fan he found Boston "a great fit."

It wasn't until he moved to the suburbs and began commuting that he returned to writing. "It never occurred to me to try to get anything published," said Hosp. "I was writing for the fun of it. The first book I tried was too close to me and to my experience. I knew the characters too well. My parents said forget it. So I did. After 150 pages I put it aside."

His next ferry effort was more fruitful. "Because I didn't have expectations about getting anything published I think perhaps, as a writer, that was freeing. Because I didn't have the time to do research I decided to write fiction. In my second try I decided to create a character who was an associate at a law firm, but to make him completely fictional. My goal was to develop this character completely and have him be unlike anyone I actually knew," Hosp says. The resulting first Scott Finn novel, Dark Harbor, "takes place in towns along my ferry commute—Southie [South Boston], Charlestown, Castle Island."

"It was a lot of fun to develop the characters, scene by scene. I got to the point where I was really curious about how it would all come out. I had no plans to get it published. I finished the book and designed my own cover and went to Kinko's, and for three or four bucks a copy they will publish it for you. So I took a picture from the ferry, played around with it on PhotoShop and made a cover."

Hosp never had to return to Kinkos to print the entire book just for fun because—with some help from a family friend, Aaron Priest, who happens to be a famous literary agent—he sold the manuscript to Warner Books, now Grand Central Publishing.

"I called Aaron in New York, not knowing that you never just call famous literary agents," says Hosp. Told that Priest doesn't represent unpublished writers, Hosp nonetheless delivered a manuscript to his office and was told theyd be back to him in three or four months. Aaron Priest was nowhere to be seen," Hosp says.

When the agent called back a week and a half later, it was a surprise. "My wife was out and the phone had just rung and the baby was crying and the dog was barking and I said, 'Wait just a minute please,' and I put the crying baby in his car seat in the other room and closed the door," Hosp recalls. "I went back to the phone and Priest said, 'You're a hell of a storyteller.' 'Thanks,' I said. And he said, 'I've been in this business for a really long time and I'm pretty sure you are a writer.'

" 'Holy crap,' I thought to myself. 'My life has just changed a little bit,' " Hosp says with characteristic understatement. And it had.

David Hosp, photographed January 13 near Boston.

When asked which is easier to write, sex or violence, he laughs— and reddens. "Violence," he says.

MARIA KARAGIANIS is a Boston writerwho was part of a Boston Globe team thatwon a Pulitzer Prize gold medal for coverageof Boston's school desegregation crisis. She nowworks as director of U.S. operations for Greece'sAnatolia College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

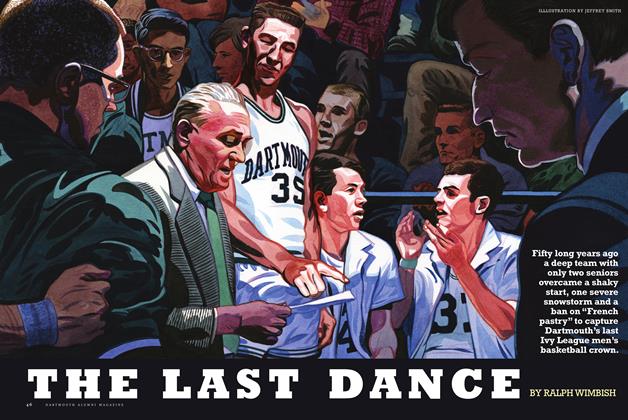

FEATUREThe Last Dance

March | April 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH -

FEATURE

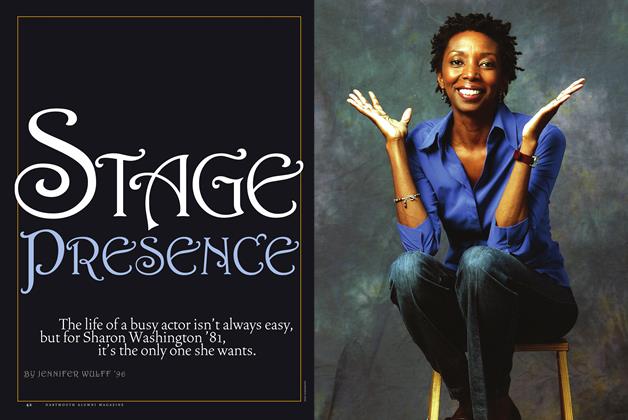

FEATUREStage Presence

March | April 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

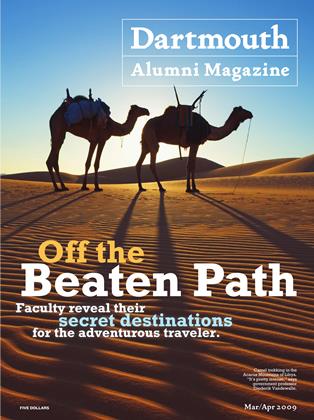

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"See the Beautiful Architecture"

March | April 2009

ON THE JOB

-

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBWorking With Obama

May/June 2009 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBKeeper of the Golden Gate

MAY | JUNE 2014 By ALEC SCOTT ’89 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBSurgical Precision

Jan/Feb 2011 By Deborah Klenotic -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBThe Navigator

September | October 2013 By ERIC SMILLIE ’02 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBGrowth Industry

May/June 2013 By Lauren Vespoli ’13 -

ON THE JOB

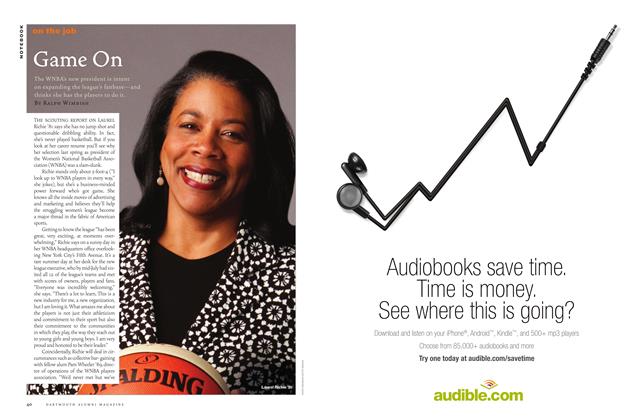

ON THE JOBGame On

Sept/Oct 2011 By Ralph Wimbish