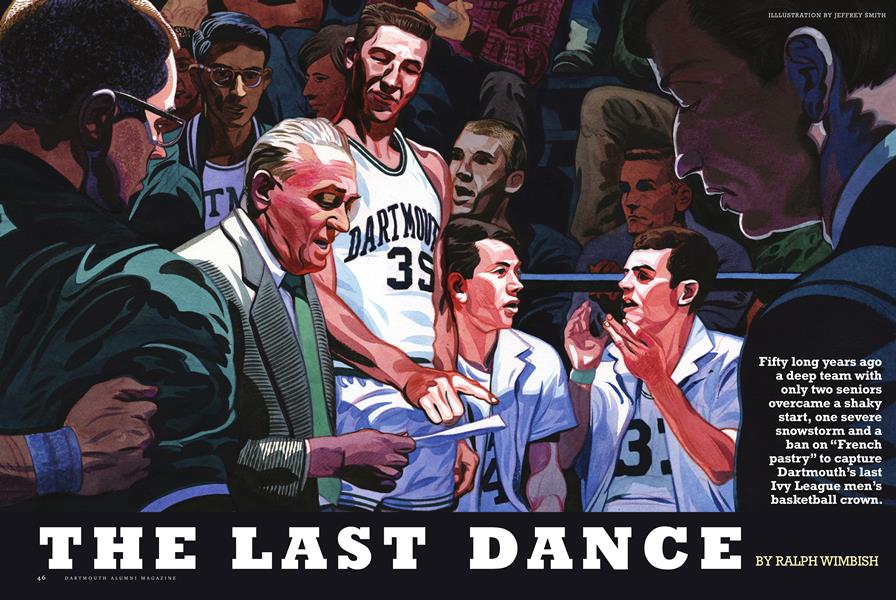

The Last Dance

Dave Gavitt ’59 is a dreamer. Always has been. Like many Dartmouth graduates he dreams of the day his alma mater wins another Ivy League men’s basketball championship.

Mar/Apr 2009 RALPH WIMBISHDave Gavitt ’59 is a dreamer. Always has been. Like many Dartmouth graduates he dreams of the day his alma mater wins another Ivy League men’s basketball championship.

Mar/Apr 2009 RALPH WIMBISHDave Gavitt '59 is a dreamer. Always has been. Like many Dartmouth graduates he dreams of the day his alma mater wins another Ivy League men's basketball championship.

In 1992, as a member of the U.S. Olympic committee, he came up with the concept of a "dream team" of big-name NBA all-stars who would win the basketball gold medal. Fifty years ago Gavitt played on a different dream team—one that won Dartmouth's last Ivy League men's basketball title.

Dartmouth's 1958-59 basketball team was truly a dream come true. Since that season only 11 Dartmouth men's hoops teams have enjoyed winning seasons (the squad has finished as Ivy runnersup five times in that period).

Gavitt and his teammates were ranked among the top 15 college teams in the country in an era without shot clocks or 3-point baskets. Winners of 22 of their 28 games that season, they symbolized a golden age of Dartmouth basketball, proudly carrying the Dartmouth banner to the NCAA tournament for a third time in five years under the coaching of Hall of Famer Alvin "Doggie" Julian.

"Doggie was one of the last great character coaches, larger than life, with lots of quirks," says Gavitt, who was head coach at Dartmouth from 1966 to 1969.

Among his many accomplishments, Gavitt became head coach at Providence College (1971-78), was the first commissioner of the Big East Conference in 1979 and was head coach of the 1980 U.S. Olympic basketball team. In 2006 he was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame. He now lives in Rhode Island, where he works as a basketball consultant.

Gavitt was one of only two seniors on the squad that season. His teammates included Chuck Kaufman '60, Walt Sosnowski '60, Gary Vandeweghe '60, Dave "Scoops" Farnsworth '60, Bob Fairbank '60, Bryant Barnes '60, Dan Berry '61, Howie Keys '61, Bob Hoagland '61 and the late George Ramming '61.

And, of course, there was that guy named Rudy.

"Rudolph Anton LaRusso was the second best player in Ivy League history behind [Princetons Bill] Bradley," Gavitt says of his good friend, who died in 2004 at the age of 66 from Parkinsons disease. "To know him is to know how tough he was. Every day he came ready to play, and you'd better be ready to play."

LaRusso '59 was an Ail-American forward and a two-time All-Ivy League selection who was recruited to Dartmouth by the legendary Al McGuire, who coached Dartmouth's freshman team from 1955 to 1957. In 1981 LaRusso was named to the Ivy League's silver anniversary team (along with Bradley, Columbia's Jim McMillian and Chet Forte and Penn's Corky Calhoun).

All arms, 6-foot-7 and 220 pounds of muscle, LaRusso was a tough Jewish kid from Brooklyn who, according to one teammate, looked like "an average Joe who drives a beer truck." But he was a rebounding machine. At Dartmouth he averaged 15.4 rebounds per game and to this day holds three school rebounding records, including the career mark of 1,239. He remains one of two Dartmouth players to surpass 1,000 points and 1,000 rebounds. (Jim Francis '57 is the other.)

"The only thing elegant of his style was the way he could take complete command of a game when it counted," author Neil Isaacs wrote of LaRusso in his 1975 book, All the Moves: A Historyof College Basketball.

"Rudy was stuck with me as his roommate that season," says Berry, LaRusso's backup that season and now a manufacturing representative in Milwaukee. "When we were in a Buffalo hotel room for a tournament, the TV next door was too loud and we were trying to take a nap. Rudy banged on the wall, and it was still too loud. He then went next door in his jockey shorts and pounded some more. On the court he was just as belligerent. You wanted him on your side."

After Dartmouth LaRusso was drafted by the Minneapolis Lakers one year before the team moved to Los Angeles, where he had five NBA All-Star seasons during a 10-year pro career. In the final game of the 1961-62 season he scored 50 points against the St. Louis Hawks.

"We became good friends when I got to L.A. and found out what type of person he was," says Jerry West, the NBA Hall of Fame guard who played at West Virginia before teaming with LaRusso on the Lakers. "We were the most physical team in the league, and he was a great rebounder, a wonderful person. And he got better eveiy year."

Ironically, West had previously gone head to head with LaRusso on March 9,1959, at New York's Madison Square Garden. Playing for West Virginia, West and his teammates knocked Dartmouth out in the first round of the NCAA tournament. LaRusso scored just 12 points that night because of foul trouble while West put on a show, scoring 27 points in an 82-68 victory.

"Barney" Barnes, now a financial counselor in his native Kansas City, Kansas, remembers the game. "I always tell people I held Jerry West to four points," he quips. "Of course I only played for two minutes that night."

That game marked the third time in five years that Doggie Julian had taken Dartmouth to the NCAA tournament. Doggie, who coached at Dartmouth from 1950 until his death in 1967, had a voice like gravel and looked like a cross between Yogi Berra and Jimmy Durante. Around campus or out to dinner with his wife, Lee, Doggie always seemed to be wearing the same tweed jacket, gray slacks and range-brown shoes.

"We loved him, but he drove us batty," says Vandeweghe, whose brother Ernie and nephew Kiki had pretty good NBA careers. "Doggie was always a little mad, a little sarcastic. When he got upset with the officiating hed take his jacket off and try to give it to the referees. 'Take my jacket, you're taking everything else,' he'd yell."

In 1947 Julian had coached Bob Cousy and Holy Cross to the NCAA championship, winning 65 of 75 games over a three-year stretch, but he was fired after a disappointing two-year stint as head coach of the Boston Celtics. Arriving in Hanover in 1950 Doggie won just three games in his first season, but it didn't take him long to turn Dartmouth into a winner. With Doggies son Toby leading the way in 1955-56, the team was crowned the Ivy League's first basketball champion.

"He kept our noses to the grindstone," says Farnsworth, now a retired public school administrator from Canandaigua, New York. "Before every game he'd always say three things: Rebound, take good shots and don't lose the ball without getting a shot."

When it came to food Doggie was a real stickler. Precisely three hours and 45 minutes before each game his players were subjected to the same pregame meal—be it at the Hanover Inn before home games or some strange restaurant on the road.

"It was a ritual," says Vandeweghe, now a tax lawyer in San Jose, California. "Doggie hated condiments, hated mayonnaise, mustard, salad dressing. Every game we had steak, baked potato, a wedge of lettuce and maybe a green vegetable. And for dessert we always had custard and tea. Never coffee, no ice cream, no milk, no butter. After the game he'd tell the trainers to give us a few nickels for chicken sandwiches. They would be plain, no tomato, no mayo, on white bread."

"I remember how the custard would shiver on the plate," says Sosnowski, now a real estate consultant in Dallas. "Afterwards I'd go out and get a milkshake."

"French pastry" was something else Doggie couldn't stomach. That was a term he would bark out whenever he saw behind- the-back passes and other plays he deemed too fancy.

"Doggie and I didn't get along too well," says Sosnowski, who, like Berry, came to Dartmouth from Cranford, New Jersey. "I had a few flashy moves. I could pass the ball behind my back and dribble—and that would make Doggie scream and holler."

Expectations were high for Doggies dream team after Dartmouth won two NCAA tournament games in addition to the Ivy League crown in 1957-58.

"The year before [1957-58] was supposed to be a rebuilding year, but Sosnowski and Kaufman came on like gangbusters," says Farnsworth, the bespectacled 6-foot-9 center.

In addition to Kaufman and Sosnowski, the strong crop of juniors included Barnes, Fairbank, a 6-foot-i swingman from Shaker Heights, Ohio, and Vandeweghe, a 6-foot-4 forward from Oceanside, Long Island.

"Gary had massive hands and a nice touch," recalls Sosnowski. "If I had his body and my mind, I'd be another Jerry West."

With Sosnowski and Kaufman starting and Gavitt coming off the bench as the sixth man, Dartmouth had one of the best backcourts in the country.

"Gavitt was a helluva player," Barnes says. "Some games he'd score only two points, then the next game he'd have 16. He was a good outside shooter."

Kaufman, like LaRusso, came from Brooklyn and became a two-time All-Ivy selection. He excelled at baseball and football, but didn't hit the gridiron at Dartmouth because he didn't get along with head coach Bob Blackman.

"I wanted to go to Princeton and play football," says Kaufman, now a telecommunications consultant who lives in Cold Spring, Long Island. "But I took the seven-and-a-half-hour ride with a friend to Dartmouth and fell in love with Hanover."

"Chuck was the floor leader, like a point guard except we didn't call him that in those days," Farnsworth says. "He was very sharp mentally. He would anticipate. Before youd ask him for the salt, hed hand it to you."

The sophomores—Berry, Hoagland, Keys and Rammingprovided depth on the bench. Hoagland, now retired after a career in manufacturing as head of the Thermos Co., was a good shooting guard from Oak Park, Illinois, but he left the team after the fifth game because of academic trouble. Keys, who retired to South Carolina after a career in human resources, was a nifty ball-handler who, like Farnsworth, came from Canandaigua High School. He was the No. 4 guard.

artmouth got off to a shaky start, losing four of its \ first eight games, including three in a row on a ) I dreary December road trip to the Midwest that J included stops at Butler, Vanderbilt and Bradley. When Tom Aley '59, Tu'6o, a 6-foot-6 forward from Chicago, left the team after the Bradley game to concentrate on getting his business degree from Tuck, Doggie shook things up by switching the rooming assignments.

"Doggie had me with Ramming," recalls Gavitt, who had been rooming with LaRusso. "We ran out of gas [at Bradley] and Doggie went off on us. He put us through a killer practice one day, and when I came back to the room I found Rammy sitting in the bathtub with a beer and a cigar. He informed me he had played his last game for Dartmouth. I got Rudy on the phone and he came down and we got him squared away."

"Rammy was a funny guy," says Fairbank, who now runs a manufacturing business in Dayton, Ohio. "He could have been the greatest player in Dartmouth history if only he could have stopped laughing in practice."

Ramming, a 6-foot-5 forward from Union City, New Jersey, subsequently sat out the rest of the season because of an ankle injury, but things began to come together when the team went to Buffalo and beat Brigham Young and Canisius to win a Christmas tournament. After an 83-66 loss at Holy Cross on January 3 Doggie's team won 15 straight games, starting with a 52-51 victory at Yale. In five of those games the winning margin was four or fewer points. On February 21 at Hanover, Dartmouth made it 14 straight, beating Princeton 71-59 in a battle for first place in the Ivy League.

After win No. 15 against Holy Cross came the "trip to hell." Actually, the destination was Princeton. Although scheduled to leave Lebanon Airport at 7:30 the night before the rematch, Dartmouths plane bound for New York was rerouted by a giant snowstorm. Conditions were so bad the plane was forced back north and landed in Concord, New Hampshire, at 2:30 in the morning. A few hours later, after a sleepless night at a local motel, the team waited for a train that never came and then took a bus to Boston, then a train to New York and eventually New Jersey.

"Doggie all the time was trying to work something out," Sosnowski recalls. "Princeton said, 'Get here or forfeit.' "

Exhausted, Dartmouth finally arrived in Princeton about 7:30 and the game started an hour later. The 15-game winning streak went down the drain with an 83-67 loss, leaving Dartmouth and Princeton tied atop the Ivy League with 13-1 league records.

Dartmouth closed out the regular season with convincing wins over Penn and Brown, setting the stage for a one-game playoff on March 7 at Yale's neutral court to determine the league champ and the winner of the NCAA berth. March Madness, indeed.

"We were pretty confident we would beat them, even in New Haven," says Vandeweghe. "It was a great game."

It certainly was. Dartmouth started fast, taking a 24-7 lead before Princeton, led by the Belz twins Carl and Herman, battled back. LaRusso picked up his fourth foul early in the second half and didn't return until there was 5:43 left in the game. By then Princeton had taken a 62-61 lead. With two minutes to go the Tigers led 66-61.

With six seconds left Kaufman scored to bring Dartmouth to within a point, 68-67, and then it got crazy. When Princeton inbounded the ball LaRusso claimed that Jim Brangan had stepped out of bounds. Doggie went nuts and argued in vain for a good five minutes before Princeton was awarded the ball near half court. When Artie Klein inbounded the ball to Carl Belz, Sosnowski crashed into him violently, knocking Belz into the second row of seats. Miraculously Dartmouth was awarded the ball, and it was Princeton coach Cappy Capones turn to go nuts.

"Belz landed out of bounds," Sosnowski recalls. "Cappy came flying off the bench. 'Sos, you did that on purpose,' he yelled at me. Then he dragged me over to the ref and said, 'Tell him, Sos, you did that on purpose.' "

With three seconds left Doggie pulled out his trusty chalkboard and drew up a play—while Kaufman and LaRusso came up with a play of their own.

"I knew [Carl] Belz would go for the ball," recalls Kaufman, who inbounded the ball. "So I gave him a good fake and Rudy broke the other way." Kaufman delivered a perfect back-door bounce pass. LaRusso dribbled once and banked in the lay-up just before the buzzer sounded.

The game was over. Dartmouth had won, 69-68, and was once again the Ivy League champion.

Fifty long years ago a deep team with only two seniors overcame a shaky start, one severe snowstorm and a ban on "French pastry" to capture Dartmouth's last Ivy League men's basketball crown.

Led by coach "Doggie" Julian, the team symbolized a golden age of Dartmouth basketball.

RALPH WlMBISH is an assistant sports editor at the New York Post and a regular contributor to DAM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

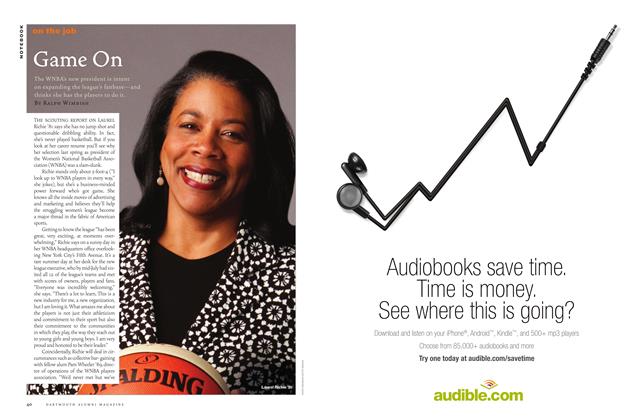

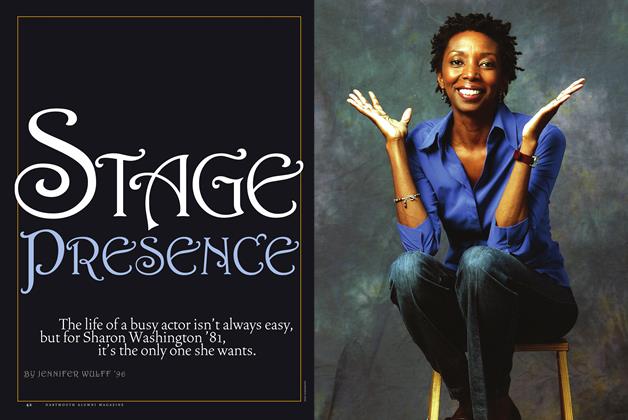

FEATUREStage Presence

March | April 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

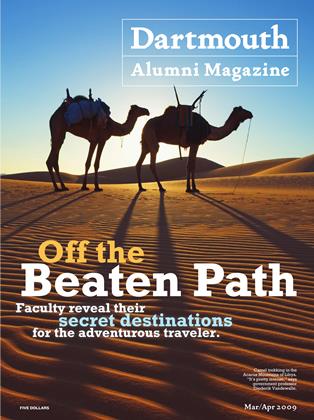

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"See the Beautiful Architecture"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Be Prepared For The Unexpected"

March | April 2009

RALPH WIMBISH

Features

-

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE CAT IN THE HAT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

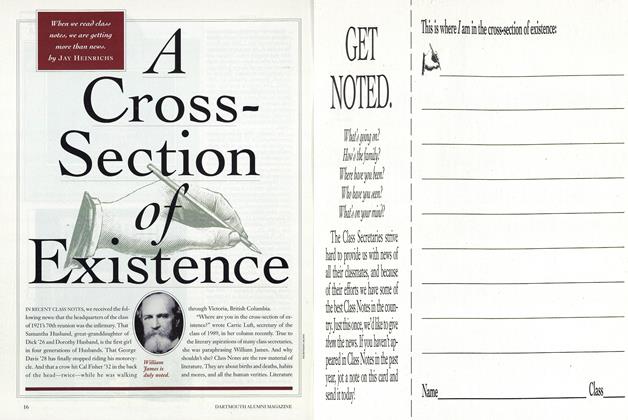

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

MARCH 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureUps and Downs in the Big Leagues

September 1979 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

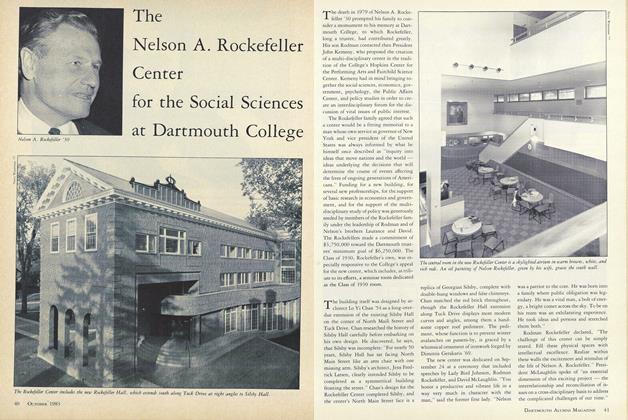

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham