No Survivors

When a small plane went missing in the White Mountains, the ensuing search changed forever the lives of Outing Club members.

Mar/Apr 2009 Karen Iorio ’10When a small plane went missing in the White Mountains, the ensuing search changed forever the lives of Outing Club members.

Mar/Apr 2009 Karen Iorio ’10When a small plane went missing in the White Mountains, the ensuing search changed forever the lives of Outing Club members.

ON THE EVENING OF FEBRUARY 21,1959, A SNOW SQUALL SWEPT THROUGH the New Hampshire mountains, blackening skies over the Upper Valley. Heavy snowfall and strong wind gusts rocked a small Piper Comanche airplane flown by Dr. Ralph Miller '24 with fellow Mary Hitchcock Medical Center physician Robert Quinn aboard. The doctors, heading to the Lebanon airport after making an emergency call to Berlin, New Hampshire, were well-known to Dartmouth Outing Club (DOC) members, so when the plane went missing later that night students played a major role in one of the states largest air and ground searches.

Miller, chair of the DOC board and a close friend of executive director John Rand '38, "was still a very active presence in the DOC," says Craig Jameson '60, who was active in the search and served as vice president of the club the following year. "I had actually flown with him once in his high-wing float plane. I remember we took off under the Ledyard Bridge, flew around Hanover for a few minutes and landed back on the river."

"He was an impressive, iconic figure," says Jim Baum '61, search coordinator and president of the club in 1961. Millers son, Ralph Miller Jr. '55, DMS'59, was a student at Dartmouth Medical School and had been a member of the ski team.

For eight anxious days DOC members—led by Rand, DMS doctor Phillip O. Nice and Dartmouth ROTC director and Army Capt. Rees Jones—coordinated more than 500 volunteers and searchers in a rescue effort. Civil air patrols of New Hampshire and Vermont, Army and Air Force planes and state fish and game, forestry and recreation departments all joined the search. "The Outing Club filled a vacuum, as there was no major leadership," says Fred Hart '58, Th'6o, then a recent DOC president still on campus doing graduate work at Thayer.

With no formal training or organized disaster plan the DOC "made it up as we went along," recalls Baum. Hed spent the previous summer working the trail crew, so, like other Chubbers, he had a pretty good working knowledge of the White Mountains terrain. Donning snowshoes and winter gear, they trudged through the wilderness in search of the doctors and their plane. Baum, a sophomore, coordinated the ground searches along with DOC president Sam Adams '59.

Other volunteers with similar knowledge of the area and outdoor skills volunteered in the makeshift search. "Students and people from the Hanover community just showed up with their own equipment and waited to be told where to go and what to do," says Jameson. "Most of us, in Cabin & Trail at least, had our own outdoor gear that was adequate to perform the search efforts."

Jameson remembers DOC offices in Robinson Hall as "a beehive of activity" as phones rang off the hook with calls about potential sightings, all of which were pursued. "I went on one such trip at night by car over into Vermont to a fairly remote farmhouse," Jameson remembers. "The house was so cold that there was a baby lying on a blanket on the open door of an oven—which was turned on—a sight that made a lasting impression."

Unfortunately, the lead proved to be a false hope, as did all the others. The search initially focused on the area around Whitefield Airport (now Mt. Washington Regional Airport in Whitefield, New Hampshire), where some believed Miller might have tried to make an emergency landing. But blustery conditions during the storm made it nearly impossible to predict where the plane could have strayed off course. "Hundreds of calls came from throughout New England from people who thought they saw or heard the plane. If we believed them all, it would have been in a thousand places at once," says Hart.

After eight days the search was called off due to poor weather and a lack of any promising leads. The effort continued to take an emotional toll on students, many of whom missed weeks of classes to follow leads after the formal search ended. Jameson describes "emergency junkies" who thrived on "being in the middle of things" and remained in the DOC offices for days on end. Hart didn't sleep for the first three days of the search before realizing the exhaustion only made him less useful to the effort—and in his classes.

The failed search had the biggest effect on Rand. "He spent weeks and months on it," says Hart, who notes that Rand had been at a California meeting with i960 Winter Olympics crosscountry officials when the doctors went missing. He had returned to Hanover immediately and inspired many to aid in the search for his close friend. "I don't think he ever got over it," says Hart.

On May 5 a pilot flying with a state conservation officer spotted the wreckage of the Comanche. Ground crews near Thoreau Falls Trail, in the 45,000-acre Pemigewasset Wilderness in the White Mountains, eventually found the siteand the remains of the two men Journals recovered at the site indicated the doctors had survived their crash and remained alive for at least four days. The doctors' notes chillingly revealed they had heard the engines of "distant planes" participating in the search.

"Overall it was a tiring, frustrating and depressing experience to go through," says Jameson. "We were glad we tried, but unhappy that we failed."

Soon after the recovery the DOC founded an emergency services program. Initially led by Baum, the group worked on local emergencies such as a fire in Etna and lost child searches in Enfield and Vermont. Baum also went on to work as a dispatcher for the local police and fire departments on Saturday nights.

Today no group within the DOC focuses on emergencies, according to president Andrew Palmer '10. But all ski patrol members are outdoor emergency care-certified, and the club is moving toward mandating wilderness first aid certification for all its leaders. "Should another event like this arise, thered be a large number of qualified people available to provide worthwhile assistance," says Palmer. The White Mountain National Forest Service would head any search, and DOC members would be able to provide logistical support and manpower, especially in the College Grant area, he adds. (The Grant, home to a small airstrip named for the two doctors, will be the site of a DOC memorial event on February 21, the 50th anniversary of the plane crash.)

Student searchers involved in what is known as the Miller-Quinn Tragedy five decades ago were significantly affected by an emergency that forced them to improvise. Baum, for one, says it changed his life. "For the first time I was thrown into a position of organization and leadership," he says. "To this day, at night or on a cloudy day, I can never hear a light plane without looking at my watch."

KAREN IORIO is a DAM intern from Oceanside, New York. She is majoring in English.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

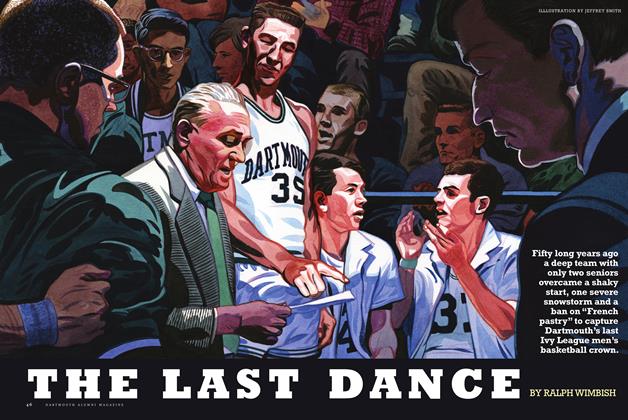

FEATUREThe Last Dance

March | April 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH -

FEATURE

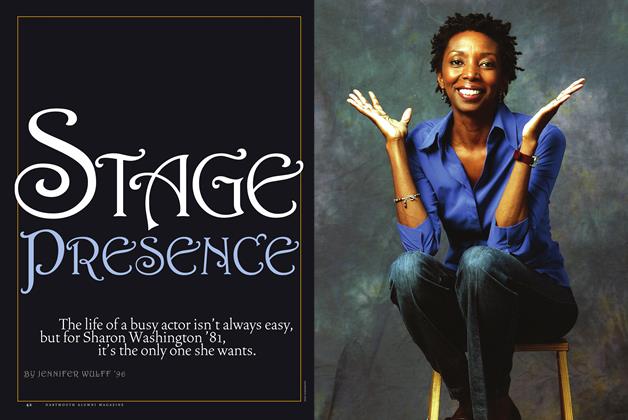

FEATUREStage Presence

March | April 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

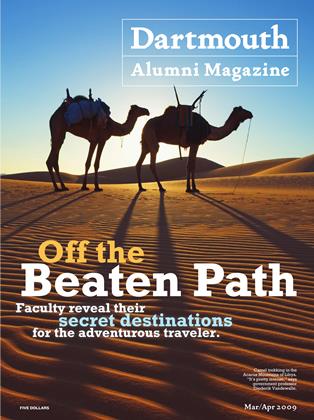

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

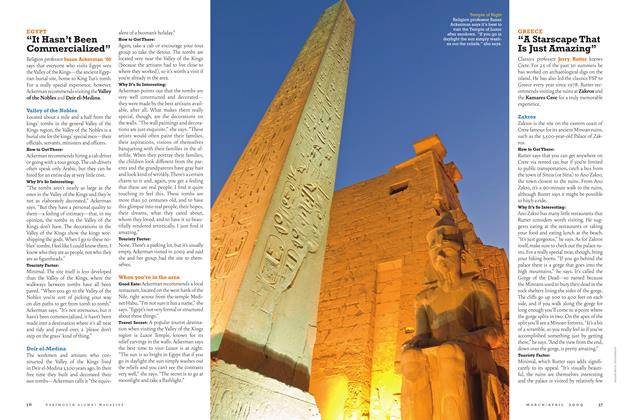

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"See the Beautiful Architecture"

March | April 2009

Karen Iorio ’10

-

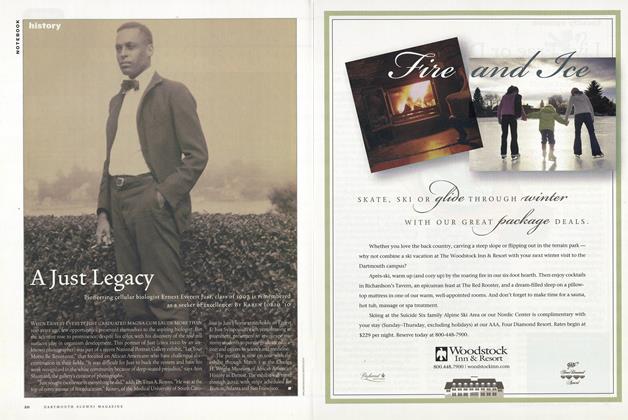

HISTORY

HISTORYA Just Legacy

Jan/Feb 2009 By Karen Iorio ’10 -

Article

ArticleGroup Therapy

Sept/Oct 2009 By Karen Iorio ’10 -

HISTORY

HISTORYIt All Started With a Letter

Nov/Dec 2009 By Karen Iorio ’10 -

Article

ArticleBirds of a Feather

Mar/Apr 2010 By Karen Iorio ’10 -

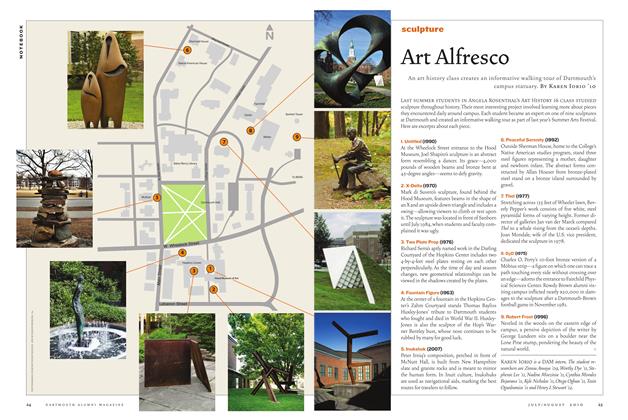

SCULPTURE

SCULPTUREArt Alfresco

July/Aug 2010 By Karen Iorio ’10 -

Student Life

Student LifeReason, Logic and Belief

Sept/Oct 2010 By Karen Iorio ’10

HISTORY

-

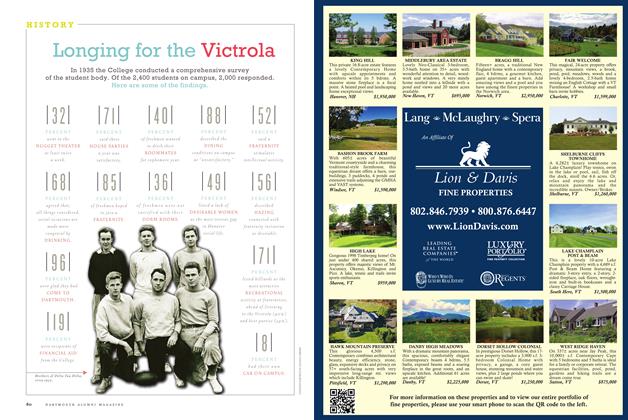

HISTORY

HISTORYLonging for the Victrola

Mar/Apr 2011 -

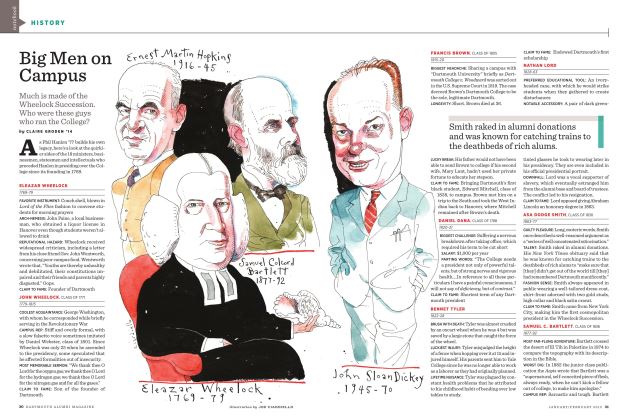

HISTORY

HISTORYBig Men on Campus

JAnuAry | FebruAry By CLAIRE GRODON ’14 -

HISTORY

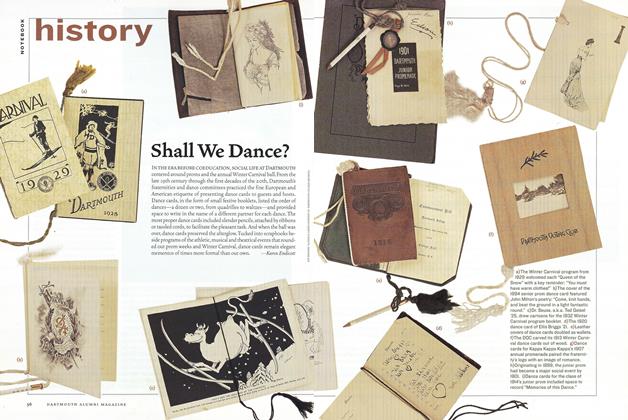

HISTORYShall We Dance?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

History

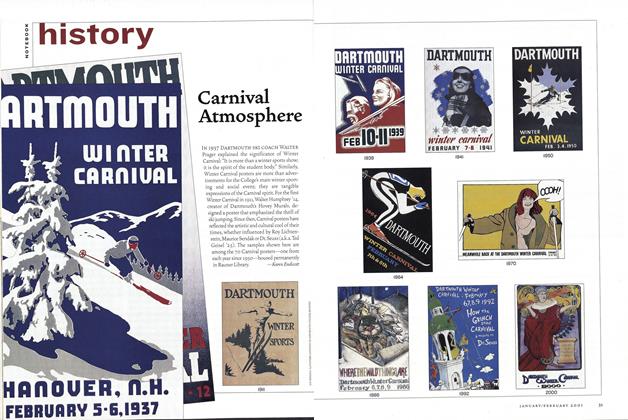

HistoryCarnival Atmosphere

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott -

HISTORY

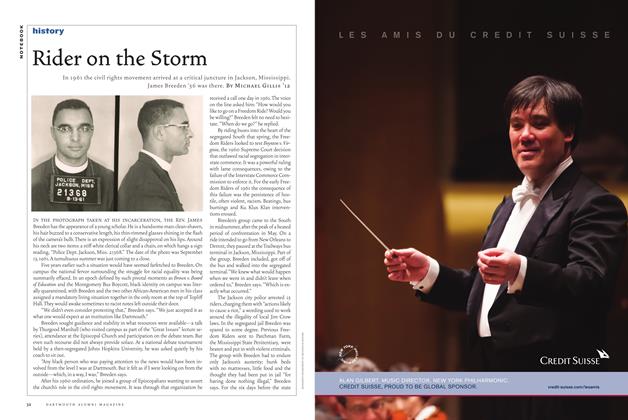

HISTORYRider on the Storm

Sept/Oct 2011 By Michael Gillis ’12 -

HISTORY

HISTORYForm and Substance

July/August 2008 By Richard Polton