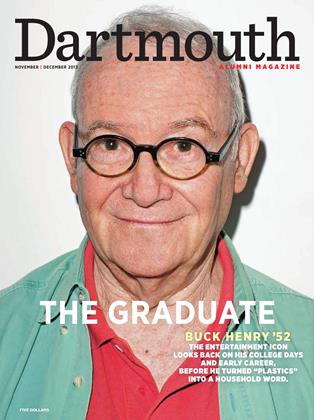

Buck Henry ’52 is one of a kind. HIS UNSENTIMENTAL BRAND OF HUMOR HAS LEFT ITS MARK ON MORE MOVIES AND SHOWS THAN YOU CAN IMAGINE. writer ty Burr ’80 recently CAUGHT UP WITH THE ENTERTAINMENT ICON TO LEARN JUST HOW THE YOUNG BUCK LEAPED FROM THE HANOVER PLAIN TO THE TOP ECHELONS OF SHOW BUSINESS. ALONG THE WAY WE LEARN THE DARTMOUTH ORIGINS OF HIS MOST FAMOUS LINE (“plastics,” anyone?), wHat a wayward kid He was and tHat He’s still funny as Hell.

Before he wrote the screenplays for The Graduate, Catch-22, What’s Up Doc?, To Die For and other classic movies of the 1960s through 1990s; before he co-created that Boomer TV touchstone Get Smart with Mel Brooks and wrote the show’s first two seasons; before he hosted Saturday Night Live 10 times in its first four years; before he played Liz Lemon’s dad on 30 Rock; before, let’s face it, he wrote the single word in The Graduate plastics—that codified everything the 1960s generation hated about its parents’ culture, he was simply Buck Zuckerman ’52.

Before that he was a precocious child who split his time between the more glittery regions of New York City and Los Angeles. And after Dartmouth—the decade or so between Ivy League graduation and pop-culture ascension—Henry lived a life of Greenwich Village serendipity at a time, the mid-to-late 1950s, when the post war counterculture was sending out tendrils in unknown directions, building toward full bloom. He was just another wannabe writer-actor in New York City, but the scene was electric with possibilities. Everything was changing—music, theater, comedy, relationships and all of it seemed to be happening downtown. Henry was there, trying to figure out what the hell he wanted to do with his life.

This is what interested me when Henry and I sat down for a long, cheerfully languorous Manhattan lunch in June: not the oft told anecdotes of his success, but the stories of the road that got him there. It’s easy to look back on a well lived life and see a succession of gold stars on a straight line, but that’s not really how it works. Most of us graduate from college as if stepping off the edge of a cliff. There’s free fall, then adjustment, then figuring out where you want to land, where you can land. We have our skill sets and ambitions, yes, but so much of it’s a crapshoot involving timing, connections and sheer, dumb luck. We really don’t know, although Henry probably does, how close the world came to not having “plastics” to rail against.

Let’s start at the beginning: A Manhattan fairy tale starring an observant little boy named Buck Henry Zuckerman. His mother was a silent movie queen named Ruth Taylor, a Mack Sennett Bathing Beauty who played Lorelei Lee in a long lost silent version of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. His father, Paul Zuckerman, was a Wall Street stockbroker who palled around with Ernest Hemingway and counted Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall as close friends. “It was New York café society,” Henry recalls. “They went out every night, very glamorous, went to endless parties. They ate at 21 and hung out at the Morocco and the Stork Club. All that was swell. I liked it.”

Henry, in fact, was something of a male Eloise. Can you really call it a childhood when you’re singing duets with Ethel Merman at your parents’ parties? When you’re performing in a greater New York touring production of Life with Father? When you spend downtime in Palm Springs, California, hanging out with Howard Hughes, the U.S. secretary of the interior and the Purple Gang? (“I played tennis with Peter Lorre and Paul Luckas, and they all could beat me easily, but they let me win.”) Already Henry seems to have had a taste for deadpan flights of fancy. An only child surrounded by adults, he invented two siblings named Arthur and Hilda and told anyone who asked that they lived in New Jersey (because, of course, “Nobody goes to New Jersey”).

“I was a shit,” Henry says. “I like me as a child less than any kid I’ve known.” It’s an insight that came to him not long after college, but it also testifies to the man’s distaste for nostalgia in its rosier varieties. An afternoon spent with Henry, now 82, is to be regaled with delightful shaggy dog tales and droll observations, all of them purged of the sentimentality with which most of us soothe ourselves.

Indeed, unsentimental is the word his two dearest friends use to describe him, and they mean it as a compliment. “Unsentimental and affectionate at the same time, and forever hilarious”that’s Mike Nichols, who directed The Graduate, Catch-22 and The Day of the Dolphin from Henry scripts.

“You can depend on him to be unsentimental all the time. He’s never going to get gooey on you, and that’s a comfort right there.” So says actor George Segal, whose friendship with Henry runs from their salad days in New York improv comedy through The Owl and the Pussycat (1970) and To Die For (1995) to the 1998 Broadway production of Yasmina Reza’s Art.

Henry has been through a bad patch of health lately, and he grows impatient with himself when the names of people and places don’t come easily. Pity, self or otherwise, is not in his lexicon. With his owlish spectacles and sideways grin under an ever-present baseball cap, he looks much the same as he always has, just more weathered and compact. He flirts with the waitress like the naughty boy he once was and still is.

He describes his schooling as of a piece with his childhood: wayward and elite. Henry went to Dalton in Manhattan, then a military school out west, then Choate, atoning for his father’s sin in getting kicked out. You would think Dartmouth would be an odd choice for a cosmopolitan boy, and you’d be right. Henry would have preferred the urban environs of Harvard, but money was tight and family connections delivered him to Hanover, whereupon he carved a niche as a very successful maverick.

“I thought it was going to be like an old movie about college,” Henry recalls now. “Guys singing all the time. As soon as I heard I had to wear the beanie, all sorts of things happened inside me. [But] I loved the freedom I had there.”

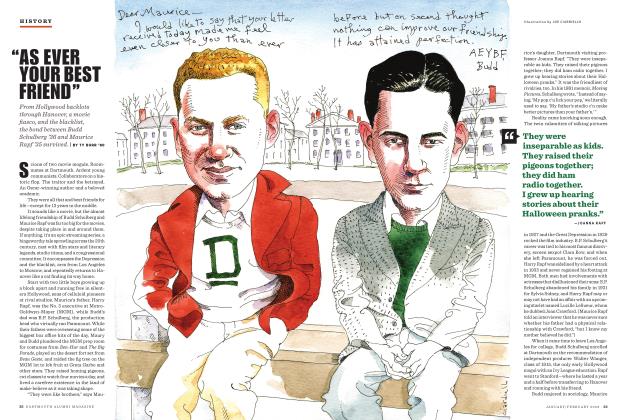

He arrived early, moved into Streeter Hall and quickly fell in with the theater crowd. “I remember doing Moliere almost immediately in Robinson Hall, Sganarelle in The Doctor in Spite of Himself,” he says. The professors of the drama department“the only three I really cared about,” says Henry were Henry Williams, Warner Bentley and Maurice Rapf ’35. The latter snapped the freshman up, beanie and all, for a short film called My First Week at Dartmouth. If you went on a freshman hiking trip in the 1970s, as I did, you saw the film on your final evening in Moosilauke Lodge, your brain trying to square that beardless youth with the devilish wit who kept popping up on SNL.

The film rendered him an early legend. Bob Rafelson ’54, who would become one of Henry’s closest friends and whose Hollywood credits run from cocreating The Monkees to directing the 1970 Jack Nicholson breakthrough Five Easy Pieces, says, “All the people who matriculated at the College were required to see an introductory film about what it was like to be an attendee at Dartmouth. And Buck starred in that film. That’s how I first met him.”

Henry also appeared in the earliest plays of Frank Gilroy ’50, who would go on to win a Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize for The Subject Was Roses (1964). He edited and wrote short stories for The Dartmouth Quarterly literary magazine—stories that are exactly the sort of overwritten, terribly serious works you’d expect from someone so talented and so young. Henry wrote for The Jack-O-Lantern, too. One surviving piece, “The Vacant Lot,” is a tale of urban misery so relentlessly depressing that a reader starts laughing uncontrollably halfway through. Unsentimental.

Recollects Rafelson, “He and I and a roommate of mine, George Robinson ’54, the enfant terrible of the philosophy department, became very close friends. Buck was not only in The Jack O Lantern, but he appeared in lots of plays with someone named Sam Harnett, and they were celebrities on campus. As I recall, Buck had a fellowship from the literature department and his job was to write a novel. He used to walk around with this manuscript tucked under his arm, and one day I looked at it and there was absolutely nothing written in it. How he got away with this, I don’t know.”

Henry’s own recollections of his time in Hanover are as dry as a martini. No fraternities for him, for one thing: “Not a joiner and not a drinker and not a sports nut. I liked sports, but I didn’t care whether Dartmouth won or lost anything.”

He remembers the local Hanover women and faculty wives who performed in plays, all talented but “some of whom were a bit neurotic, had affairs with people they shouldn’t have had.” He tells of bringing the young Stan Brakhage ’55, soon to become a titan of American experimental film, back from the brink of a nervous breakdown. (Brakhage, who died in 2003, is so revered that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Archive is preserving all his work.)

Henry also spins the tale of getting done up in drag to attend a gender-segregated screening of a “birth of a baby” sex movie in Lebanon, New Hampshire, on assignment for The Dartmouth. “There was a fabulous woman who lived in Hanover named Jinky something. I think she was related to the president. And she fixed me up with hair and makeup,” he says.

Then there’s Dartmouth philosophy professor Eugen Rosenstock Huessey, who may arguably be responsible for the word plastics lodging in Henry’s impressionable brain. “He had fled from some country during the Second World War, settled in Hanover and was a real firebrand,” Henry says. “He liked to talk about America being displaced, being subject to what he called ‘tin can democracy.’ And ‘plastic’ being a life we lived that wasn’t quite real. I didn’t really take that from him any more than you do when you’re writing a scene. You know, you improvise, and ‘plastics’ sounded good to me, so there it was.”

Henry graduated, as we all must, and ambled aimlessly back to Manhattan, where he appeared in a three-character off-Broadway play (“sometimes the three of us outnumbered the audience by one,” he says), entertained vague, glorious notions of a writing career and got quickly snapped up by the U.S. Army. After two years in Stuttgart, Germany—Henry’s main claim to fame was co writing a musical called Beyond the Moon, which toured the bases of Europe he returned to New York still bristling with wit and still clueless about his future.

Anything and everything was happening in downtown tan in the mid 1950s: Off Broadway was exploding, the folk music revival was kicking in, improvisational comedy had taken off. Living was cheap, and it had to be. Henry shared a cold-water flat on West 10th Street with two friends “in the halcyon days of the West Village, where you could have a great meal for $3 and off-Broadway was $4. Improv was starting to happen, rent parties where I would hear Harry Belafonte sing and Lenny Bruce entertain for a dollar in a hat. It was a fabulous time,” he says.

Henry’s employment was haphazard; sometimes it even paid. He dubbed foreign-language films such as Russia’s The Cranes Are Flying and the Italian Hercules movies for the U.S. market. (“I was young Ulysses: ‘Over here, Hercules! And don’t listen to the sirens!’” he says. “It was a lot of fun and it was $100 a day. I lived off it.”) His lowest ebb came when he toured small towns and schoolhouses in North Carolina with a low-budget theatrical organization. In a 1958 letter to his Hanover mentor, Professor Williams, Henry describes the troupe as “a harebrained rattletrap menagerie of dedicated has- beens and apprentice failures who have been wandering up and down the Carolinas for 25 years, cramming their singularly oppres- sive brand of homespun drama down the throats of unsuspecting schoolchildren.” He eventually hightailed it back to Manhattan on a late-night bus.

Henry’s most eccentric stint during this period has to have been his role as G. Clifford Prout, a mealy mouthed spokesman for the wholly fictional Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (SINA). The brainchild of a media prankster named Alan Abel, SINA was ahead-of-its-time performance art: An organization putatively dedicated to putting pants on dogs, elephants and other mammals to spare humans the embarrassment of seeing them naked. “Pure Dada,” in Henry’s words. As Prout, he appeared on TV news reports, on talk shows and in newspaper articles, all of them oblivious to the hoax. People actually wanted to join up: “We got money we had to send back and requests for membership cards,” Henry says. “Then Alan put out the SINA magazine, which is pretty sensational, with a clothed horse on the cover. I wrote the anthem. I’d play it for you if I had my ukulele here, it’s quite moving.”

In 1962 Henry was invited to join the downtown improv comedy troupe The Premise, his first regular, paid gig. Replacing the group’s director, Theodore Flicker, on stage, Henry was the garrulous audience point man, while the other cast members, including a young George Segal, handled the heavy comedic lifting. Recalls Segal, “[Buck] brought intellect. We went with emotions and he went with mind. It was a great contrast. I was flopping all around and he would stand there and comment. But always funny.”

Here’s where the connections happen those invisible webs that link one person to the next and lead us to places we never suspect. Henry’s Dartmouth friend Rafelson was by then working in New York for producer Dan Melnick at ABC. Rafelson went to The Premise, then came back with his boss, who decided that Henry had the off-the-wall sensibility to write for Steve Allen’s TV show in L.A. The next thing Henry knew, he was at the West Coast writers’ table, working alongside comedians’ comedians including Dayton Allen and Stan Burns.

That lasted a bit, and then Henry was back in New York, writing for Garry Moore’s show, writing and acting in the satiric news show That Was the Week That Was and co-writing and starring in his first film, The Troublemaker, a 1964 fiasco that utilized the talents of The Premise crew (minus Segal) and almost bankrupted financier Janus Films. The Rafelson-Melnick connection got him back in bed with Get Smart, and Henry returned to Los Angeles. It was there that he started hanging out on the set of the movie his buddy Segal was making. It was called Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and its director was Mike Nichols.

Henry says he and Nichols bonded through their mutual sardonic, New York wit on the film set. Nichols remembers it slightly differently. In 1965 actress Jane Fonda hosted a legendary Malibu birthday party for her father, Henry Fonda a bash that threw together Old Hollywood and New in a spirit of mutual incomprehension. Nichols was invited; Henry and Rafelson snuck in with friends via the beach. It was the 1960s: The Byrds were playing in the back yard, recalls Henry, and “we stopped for a long time to observe in a car outside the house a very well-known writer [engaged in a sex act] with a very well-known actress.”

Remembers Nichols, “Buck was with some people sitting under a tree, bullshitting, and I was standing there and he said, ‘How do you like it out in L.A.?’ And I said, ‘Here under the shadow of the great tree, I’ve found peace.’” Only two New Yorkers in Lotusland could understand that sentence to be a gentle but unmistakable put down of everything surrounding them.

“I had already had two drafts of The Graduate with which I was very unhappy,” continues Nichols. “Now I’m talking to Buck, and I knew that he had improvised in another group while I was in Second City. He was so smart and so funny that I said to him then and there, in that conversation, would you be interested in having a look at this book I’m wanting to turn into a movie? And he said he would.”

There’s the creation myth for you: Nichols handing The Graduate to Henry like a scene from the Sistine Chapel. So what if Henry remembers it differently, that he befriended Nichols before, on the Virginia Woolf set, and was offered the writing job later? It sounds as if it was a hell of a party, and maybe memories get drawn to such moments as do iron filings to a magnet.

However the novel of The Graduate passed from director to writer, right here is the nanosecond that Buck Henry’s apprentice ship in life ended and his career truly began. The rest is the kind of history you can see for yourself. If you haven’t, you should.

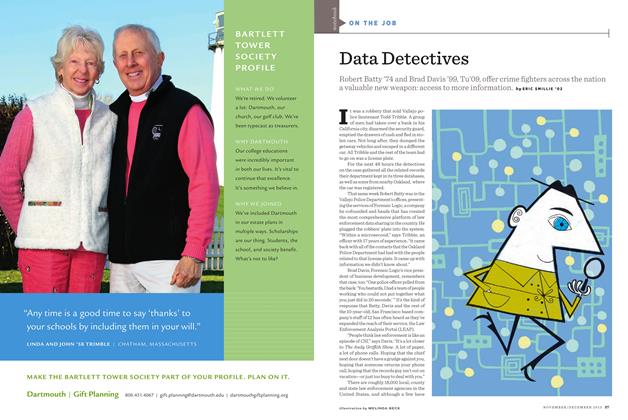

OLD SCHOOL “I thought it was going to be like an old movie about college,” Henry says of his arrival in Hanover. Actually, the movies came later. Here he is hard at work on The Owl and the Pussycat, one of five screenplays he wrote during the 1970s.

Buck Henry WASN'T ALWAYS Buck Henry.

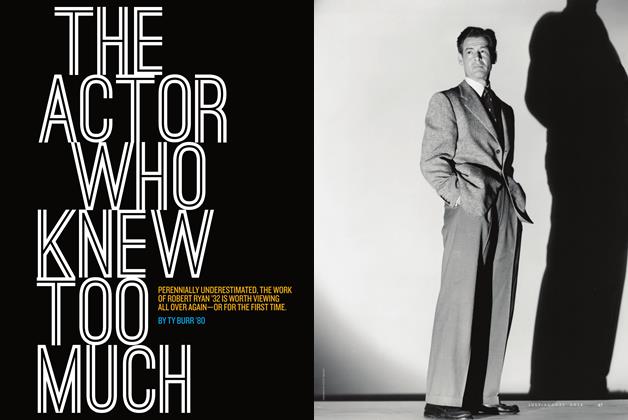

Ty Burr, who wrote a profile of actor Robert Ryan for DAM in 2012, is a film critic for The Boston Globe and author of Gods Like us: On Movie Stardom and Modern Fame (Pantheon, 2012). He lives in Newton, Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStrangers in a Strange Land

November | December 2013 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

FEATURE

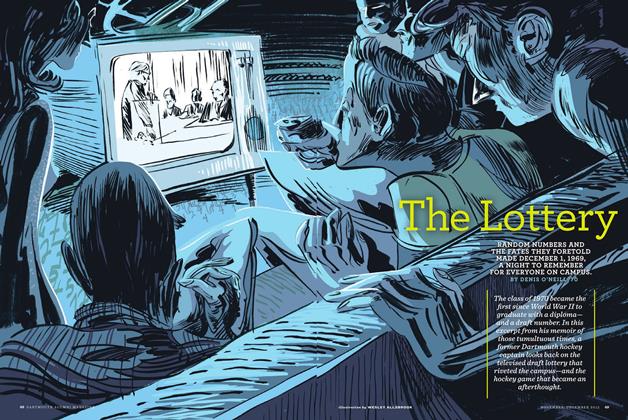

FEATUREThe Lottery

November | December 2013 By DENIS O’NEILL ’70 -

Feature

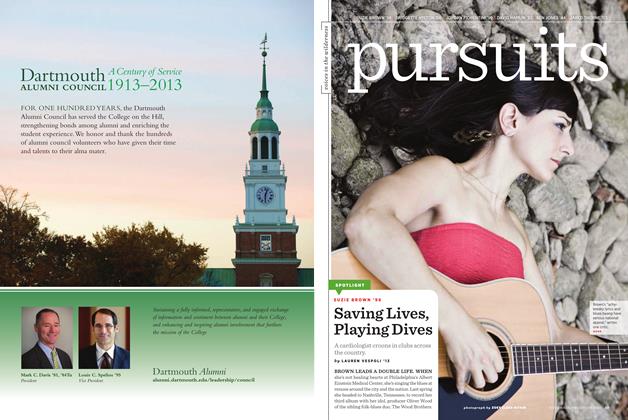

FeaturePursuits

November | December 2013 By ZOEY SLESS-KITAIN -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEHe Wept Alone

November | December 2013 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBData Detectives

November | December 2013 By ERIC SMILLIE ’02

Ty Burr ’80

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCharles Faulkner Professor of Patholog! 10,000 feet in a single wing

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureThe American Dream

JANUARY 1972 By A.T.G. -

Cover Story

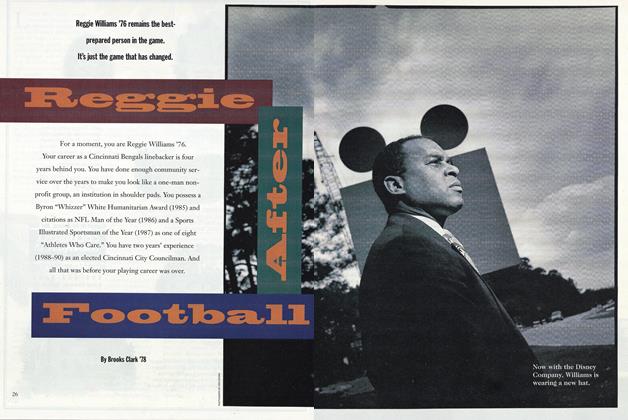

Cover StoryReggie After Football

May 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

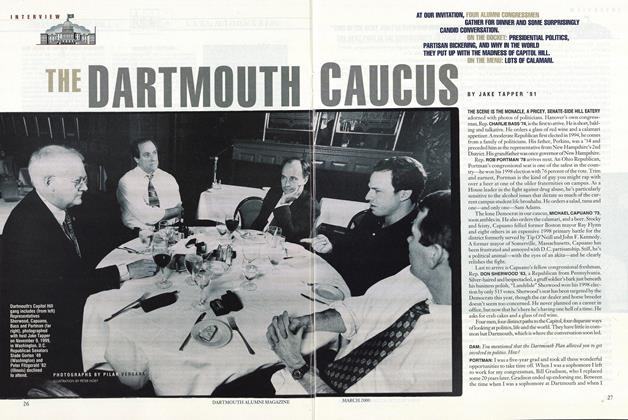

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

MARCH 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

DECEMBER 1968 By Susan Liddicoat