Reggie Williams 76 remains the best prepared person in the game.It's just the game that has changed.

For a moment, you are Reggie Williams '76. Your career as a Cincinnati Bengals linebacker is four years behind you. You have done enough community service over the years to make you look like a one-man nonprofit group, an institution in shoulder pads. You possess a Byron "Whizzer" White Humanitarian Award (1985) and citations as NFL Man of the Year (1986) and a Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year (1987) as one of eight "Athletes Who Care." You have two years' experience (1988-90) as an elected Cincinnati City Councilman. And all that was before your playing career was over.

Finally letting your battered knees take you out of play, you stayed in football as general manager of one of the NFL's international league football teams (1991). When that league folded you finally left your beloved football for good.

It could have been a sad time, leaving the sport you so clearly loved. Instead you made "retirement" one of the triumphs of your life: following the Los Angeles riots, you conceived, planned, and completed construction of the NFL Youth Education Town in South Central Los Angeles, getting the whole thing done in a seemingly impossible six months.

Now a 39-year-old man with a reputation for getting things done, you are invited to conceive and execute a plan for the all-time greatest of entertainment empires, the Walt Disney Company. Disney has an idea that it wants to build a sports destination in Orlando. And why not? It owns an NHL team and it is bidding for a bowl game in Anaheim. It is politicking for a major-league baseball team in Florida. And it is already building a sports hotel and resort. Your job handed down in a chain of command leading right up to Michael Eisner himself is to open a new sports center by the spring of 1996.

Being a rational, imaginative, can-do kind of person, you ask yourself the first logical question: What the heck is it going to be, anyway?

But we can't kid ourselves. We are not Reggie Williams. We most of us have never executed well-thought-out plans to crush quarterbacks behind the line of scrimmage. We have never performed a minor miracle in an L.A. ghetto. Most of us have never even been elected to office. But we did graduate from Dartmouth, and that gives us the opportunity to follow Reggie vicariously as he embarks on a new life: that of businessman.

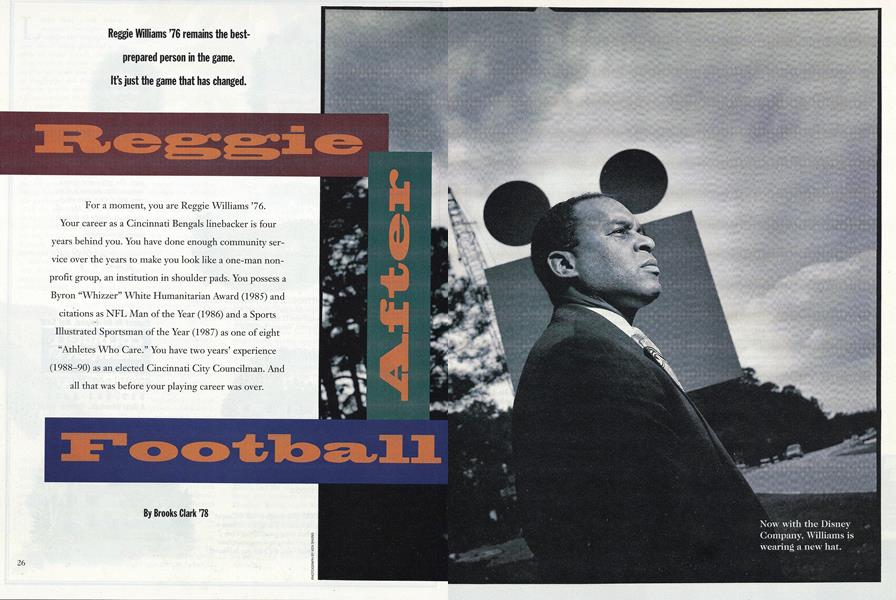

TEAM DISNEY IS THE NAME OF THE CORPOrate headquarters in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. Walt Disney Company Director of Sports Development Reggie Williams drives his Jaguar into the parking lot under several 20-foot-tall gray metal tubes bent in the shape of mouse ears. He parks and walks under another, wider set of conceptual mouse ears into the building's entrance. There are no six-foot Disney characters to meet visitors and shake their hand. The building may be vintage 2003. But it's all business.

In a thirdfloor meeting room with windows that show a view of scrubland, Reggie stands beside a satellite view of central Florida, pointing at Disney properties and updating his staff on the mammoth project. The public has been told that it will be an $80 million amateur sports center covering nearly 100 acres. It will include a 7,500-seat main-event stadium, a giant multi-purpose field house, a 2,000-seat tennis arena, multisport practice fields, running tracks, fitness center, and training facilities. "It will provide professional-caliber training, competition sites, and vacation-fitness facilities for at least 25 individual and team sports in its initial phase," says the press release. Reggie has the framework to make it the ultimate sports destination, a unique place where families, vacationers, athletes can all come together and experience sports as participants and spectators. Beyond that the details are secret, and in the cutthroat business of theme parks will probably stay that way.

Williams sits down at the conference table and discusses three or four important points with each person, directing, redirecting, pointing out pitfalls, making sure nothing falls through the cracks, nothing lies unattended and undone.

This is a man who has outworked the competition even before he ever had any, when his only opposition was his own handicap. As many readers of this magazine know, he had trouble in school as a child; he did well on tests but couldn't respond in class. When he was in third grade an alert teacher had him tested; he had only 60 percent of his hearing. Reggie was enrolled in the Michigan School for the Deaf, where he got the therapy that returned him to a mainstream school in sixth grade.

Williams returned the favor by working in Partners in Education, an alliance of Cincinnati businesses and the publicschool system. He crusaded against drugs with the White House Conference for a Drug-Free America. He established the Reggie Williams Scholarship Fund, which helped more than 100 kids go to college. He did TV ads. He spoke to groups.

In 1988 Reggie was appointed to a seat on Cincinnati's city council. He was elected the following year. Councilman Williams pushed through a local divestiture act that made the city sell off $297 million of its $900 million pension fund from companies that did business with South Africa. He also surprised members of the liberal community by supporting the rights of gun owners against a 15-day-waitingperiod law. There were plenty of hunters on the Bengals, and they had given Reggie an earful. Afterward, said Williams, those players felt they were getting input into the city.

"He is an intensely capable man with a deep intelligence," says Tyrone K. Yates, who succeeded Williams as councilman in 1990 and is now the vicemayor of Cincinnati. "He has a sense of inner security that is sufficient to take on any individual or institution if he thinks the public interest is being harmed. He has a way of shaming the status quo because of its inaction or apathy, saying, as John Kennedy would, 'We can do better. We can do more.'"

"Politics was a fabulous learning experience," says Reggie. "And I got an appreciation for a lot of detail in another profession."

He already had an appreciation for detail in football. "Each and every time I approached the line of scrimmage there were a thousand details that had to be exact for me to be successful," says Williams. "From the distance I was from the line. To my stance. Where my feet were positioned. Where my head was in proportion to the blocker's nose. What keys I was looking for in the offensive backfield. What was the down and distance. What was the weather? What kind of shoes did I have on? What injury was I sustaining? What were the guys on my right, left, and back's jobs and responsibilities? If they did their jobs what job would I do? It they made a mistake how 'would I compensate?

"So all those details flash in a second as the offense comes out of the huddle. They have control of motion, snapcount, the audible—a complete change in circumstances. And we ourselves can audible. I think people underestimate the thinking process that you use in a football game—or maybe I'm an exception, because my whole thing was being assiduously prepared. There were options and there were percentages. You rarely could play your hunch. I never was a shoot-from-the-hip-type player. It's all anticipation. You study, study, study, study film. You practice."

After 14 years as a player, in 1991 Williams took a job as general manager of the New York-New Jersey Knights of the World Football League, which was the NFL's attempt to expand the game. He had to start the team from scratch in January for a season starting in March. When the league folded, Reggie stayed on as an executive with the NFL. In late October of 1992, Jim Stieg, the NFL's executive director of special events, came to Reggie with a problem. Three seasons before, the Super Bowl had been played with the gruesome backdrop of Miami in flames. Afterwards, the NFL had begun a policy of doing something for the have-nots in Super Bowl cities instead of simply partying with the Super Haves. In 1992, with L.A. burning and the big game slated for the Rose Bowl, it was imperative that the NFL leave something behind. There was no clear mandate. So Williams took control and came up with an idea that bears the stamp of his character and values. He recommended that the NFL sponsor, of all things, a study-skills center. The result was NFL Youth Education Town, located in Compton, the neighborhood featured in the film "Boyz N the Hood." Ten thousand square feet of classrooms, study rooms, a strength and cardiovascular conditioning room, computer labs, and a library, plus another 10,000 square feet of outdoor recreation areas—the NFL kicked in a million dollars, but the rest was all Reggie's power of persuasion. He got Sony to contribute CD-ROMs and other electronic equipment. Garth Brooks gave the proceeds from two concerts. The Balsam Corporation gave the artificial turf for the football field. Sports Illustrated and SI For Kids sponsored the library. (They pay the librarians' salaries and tapped various Time Warner publishing units to donate books and magazines.) Digital gave $100,000 worth of personal computers. "Fifty-five of 'em," says Mike Davis, the ex-Raider safety and executive director of Youth Education Town. "The fanny thing is, we need more." The 550 kids in the program get tutors and help with homework. And the whole thing was completed in six months—a feat that Reggie-watchers attribute to the man's combination of charm and abrasiveness.

"There's no bullshit," says Alvaro Saralegui '78, the general manager of Sports Illustrated. "He will ruffle some feathers because he's getting things done."

"I'm totally honest," Williams admits. "It's my biggest fault and also my biggest asset."

Before the Youth Education Town was finished, Williams was getting to know the people at Disney, partly through Mike Montgomery '76, then the treasurer of Disney, now the chief financial officer of the financially awful Eurodisney theme park.

"We wanted someone who knew sports," says Al Weiss, a vice-president at Disney and now Williams's direct boss. "But he had also set up a business from scratch in an entrepreneurial environment, and that's what we're trying to do here. Another thing we try to do is get people who fit from a personality standpoint, and he really did that."

"The reason I'm at the Walt Disney Company is that it is a can-do company," says Williams. The location doesn't hurt either. He decided on the job for sure when he flew for an interview in Orlando. New York was snowed in, and Williams's knees were hurting. He has had three operations on his left knee, and that's the good one. The right one will eventually have to be replaced, and since an artificial knee is good for only ten to 15 years, Williams hopes to put off the operation as long as possible, enduring the pain along the way. The Disney job was the perfect thing for Reggie, and so was the balmy location. The only problem was, he still had to finish up the Youth Education Town. Disney said go ahead, and so for two months he was doing two jobs and commuting between L.A. and Orlando.

WILLIAMS LIES ON THE CARPET OF HIS DEN

watching the Sunday football games. His one-year-old son Kellen is standing up, alternately bracing himself against his father and climbing him like a mountain.

"Eh!" exhorts Kellen.

"Eh," Williams answers.

"Eh!" Kellen repeats.

"Eh!" Williams agrees. The Sunday Orlando Sentinel is on the floor. Eleven-year old Julien and nine-year-old Jarrel come and go. Nowadays Williams spends his autumn Sundays like everybody else. From Wednesday through Saturday he was in Anaheim syner gizing with the Disney bigwigs. But today is family time. "That's a priority for me right now," he says.

The Williams house is on a beautiful lake. The yard is fall of fruit trees. Marianna Williams is a designer, and the decor of their home reflects it. Earlier in the day Williams pulled his older boys behind the motorboat in their donut-raft and took a guest on a water tour of the local scenery-Shaquille O'Neal's compound on that shore, Wesley Snipes's on this one. "I've lived a whole lifetime of routine," says Williams. "Practice at this time. Film at this time. Bus leaves at this time. Game at this time. I've been successful at it. Now I'm just looking for a different lifestyle."

Another change: going from being a star to being a part of a hierarchy. Disney is among the most visible companies in America, and Williams's job is as glamorous as any. But there is a difference between being on the cover of Sports Illustrated and being three levels down the ladder from Michael Eisner (or, to put it another way, four down from Mickey Mouse).

"It was sure nice when I didn't have to wait in line at restaurants," Williams admits. "There are certain advantages to it. But it's like Andy Warhol, you know. I had my moment—my 15 minutes plus. I feel like I've had my time in the spotlight. Now it's time to put my kids in the spotlight.

"I'm more committed to things now that in some way, shape, or form affect them. I'd love to spend time with them as they develop academically and athletically, and in developing relationships with other people outside the family. I want to know how they're making those adjustments—like coming to grips with peer pressure. The proudest I've been of my little guy, Jarrel, was when we went to an Orlando Magic game. For some reason, Clyde Drexler has always been his favorite player. We're there in the ORena and everyone's cheering for Shaq, yet every time Portland scores there's a little tiny soft clap. He was cheering that team all by himself. To me that's a big part of what young people really have to come to grips with: what and who is going to sway you."

Like son, like father: Williams crossed the picket lines in the NFL player strike of 1987. "I did. I would do it again. The reason is I love the game."

Williams mentions that his last game was Christmas Night, 1989. "We lost," he says. So he must have ambivalent feelings about leaving the sport, right?

"The pure and simple truth is that I'm not ambivalent. If I could play I would be playing. But I can't play any more, plain and simple. It's a hell of a great game. It's a tremendous challenge. I was competitive every single year I played. There's realistically very little in life to compare to it, and if I could play it I'd play it. Hey, it's over. So that's how you move on."

"He's a guy who always wants to challenge himself," says Saralegui, "and he wants to grow."

ON ONE WALL IN Williams's Disney office is a 3-D collage given to him by the Bengals on his retirement. On a credenza is the 1976 Aegis and a plaque for the Big Green's 1973 Ivy football title. On another wall is a poster from the Munich Olympics of 1972. On another is an uncut sheet of football cards, set in Plexiglas, from Reggie's rookie season. Among the sideburns, goatees, and Afros are guys like Chris Hanburger, Joe Theismann, Ken Houston, Tom Jackson, Craig Morton. Like so many seventies things, it looks like a long time ago. When the Disney people talk about Reggie they don't mention football.

"We had an embryonic idea," says Al Weiss. "And Reggie's really crystalized our thinking on it. He's gotten people in the company excited about it and we're working on a very quick timetable because of his leadership."

"The ultimate sports destination in America." That is what Williams has in mind. We all have places we can watch sports. And there are training meccas—Colorado Springs for Olympians, Eugene, Oregon, for runners. There are sports centers for swimming. There are fantasy camps, family camps, kid-sports camps. But what if somebody put them all together? College, high-school and youth-league teams. Amateur and senior athletic groups. Individual pros, even pro teams in training. Hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. A staff of 100 trainers and coaches. Eventually the complex will include a hockey rink, Olympic-sized pool, and a sports dormitory.

This is all part of a huge plan, of course—including the biggest hotel expansion in the history of Walt Disney World. Disney's All-Star Sports Resort is opening up this summer, to be followed by four other theme resorts—the Wilderness Lodge and Wilderness Junction Resort, All-Star Music Resort, Coronado Springs Resort (recalling the romance of sunny Spain), Boardwalk Resort (capturing the atmosphere of turn-of-the-Century Atlantic City)—all of them in Orlando. The expansion will total some 10,000 rooms by 1998.

But the sports park will be something else, with an integrity that the average "American Gladiators" viewer might not expect. For one thing, we're talking serious sports. "Sports is perceived as entertainment, but in 14 years I never said, 'Let's go out and entertain somebody,"' Williams says. "In order for the center to be taken seriously, the sport itself must be taken seriously." Disney will organize championships and major tournaments in many sports. The corporation hopes to have a majorleague baseball team use it for spring training.

Williams also wants the park to be intimate—the way spring training used to be. The visitor will experience sports as a participant, spectator, coach, even broadcaster in a beautiful, personal atmosphere. With luck the world-class athletes will like it, too. With luck it will come to have status of its own—appearances on "Sesame Street," that sort of thing. Think of your eight-year-old saying, "My soccer team trained at Disney Sports World! And so did my Dad! And so did the U.S. National Team! And so did Shaq! They're my buds!"

Williams presented his plans to Michael Eisner in January and got the go-ahead to break ground this spring. Most of the facilities could be ready for athletes' final preparations for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, which somehow doesn't seem so far off.

A LONG TIME AGO, WILLIAMS SAW A PSYCHOLogist's definition of a linebacker as a guy who in time of war gets sent on a suicide mission behind enemy lines, returns after completing the mission and says, "That was a great assignment. What's next?"

If you're the quintessential linebacker, it's only a matter of time before you ask that question again.

A former writer-reporter for Sports Illustrated, Brooks Clark'78 is a freelance writer in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Dartmouth'sreigning Class Secretary of the Year.

Now with the Disney Company, Williams is wearing a new hat.

At 2 1/2, Reggie was smart but part deaf.

Sons Julien and Jarrel and the big Orlando lake house.

Reggie before he pumped tip and ditched the 'fro.

He went to the NCAA wrestling nationals as a junior.

The rookie draftee shared some skin with Bengals scion Mike Brown '57.

As a Bengal in Japan he met a colleague from a different sport.

As a new city councilman, Reggie listened to his gun-toting teammates.

He has had three operations on his leftknee, and that's thegood one.

William took a, guest on a water tour of thescenery-Shaquille O'Neal's Com pound on that shore, Wesley Snipes's on this one

There is adifference between being on thecover ofSportsIllustratedand beingthree levelsdown theladder fromMichaelEisner (or, toput itanotherway, fourfrom Mickey mouse).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

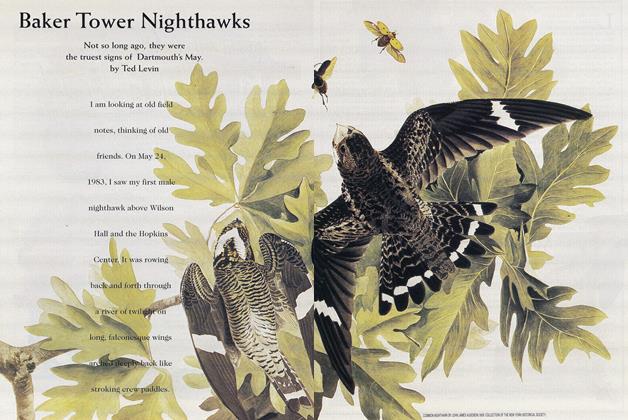

FeatureBaker Tower Nighthawks

May 1994 By Ted Levin -

Feature

FeatureCOOL STUDIES

May 1994 By KAI SINGER 95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman

Brooks Clark '78

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2008 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPease Out There

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleFAMILY TIES

SEPTEMBER 1997 By BROOKS CLARK '78 -

Article

ArticleReservation for a Clinic

NOVEMBER 1997 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleTucter's Foundation

MARCH 1999 By Brooks Clark '78

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Plan

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Feature

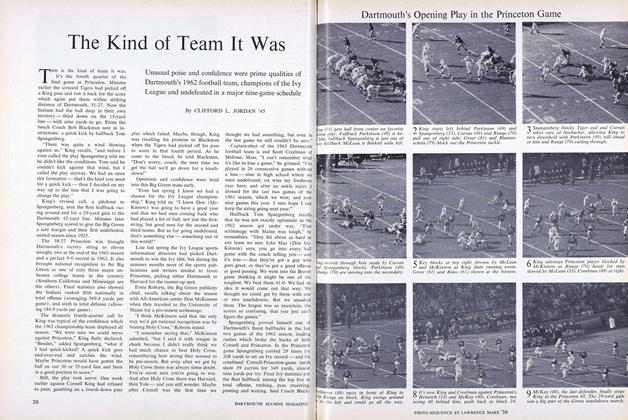

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55 -

Features

FeaturesGreatest Hits

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By Ty Burr