The Making of a Book

One day in 19771 was sitting in my office minding my own business when out of the blue came a telephone call from a Yale colleague I hadn't seen in years. He was organizing a Shakespeare festival at the Pratt Insitute in New York and thought it would be a good idea to have a lecture on Shakespeare and the black actor. Did I know anyone who could do this?

Well, I was pretty sure no one in my circle of friends or any scholar of my acquaintance was working on this topic and I had the feeling somebody ought to be. There was surely a story to be told and it was time someone got to work on it. I had always had a passion for Shakespeare. In my younger days I used to give public recitals of cuttings from his plays on the slimmest of excuses, and if ever I had succumbed to the temptation to become a professional actor, I knew I would have wanted to play all the great Shakespearean heroes. I also knew that would probably mean I would starve. These and other wistful thoughts coursed through my mind as my friend waited patiently on the other end of the line for an answer. I heard myself say: "Oh, I think I can get something up for you!" That was eight years ago.

I knew of a splendid biography written by Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock about one of the great Shakespeare actors of all time who happened to be black. The book had first been published in London in 1958 and was out of print, but a paperback edition had come out in the United States to cash in on the demand for black literature during the civil rights struggles of the late sixties and seventies. Now that black is no longer beautiful in the public mind, the paperback has been remaindered. I was able to purchase a batch of them quite cheaply and have been presenting copies to honors students in my Black Drama course. Incidentally, although I didn't become a professional actor, many years ago when I was a drama student in London, the same Herbert Marshall directed me in an American play called Longitude 49 which was presented at the Unity Theatre. The part I played had actually been created by Sidney Poitier in the American premier of the play and that was the closest I ever got to histrionic fame.

The subject of the biography, Ira Aldridge, was born in New York in 1807. At age 17 he went to London as steward to an English actor with the intention of becoming a professional himself. He died on engagement in Poland after a spectacular career of 43 years. Aldridge performed not only throughout Britain but in many European cities as far north as Moscow, as far east as Constantinople, and as far south as Zagreb. His principal Shakespearean roles included Hamlet, Lear, Macbeth, Shylock, Richard III and, of course, Othello. In an age of superb Shakespeareans, he was called "the greatest of all actors."

Well, here was a starting point for my lecture, but what next? I knew of Paul Robeson's record-breaking 1943 Othello in New York with the lovely Uta Hagen as Desdemona and Jose Ferrer as lago. Before that, there was the famous all-black "Voodoo" Macbeth directed by Orson Welles with the Federal Theatre Negro Unit in 1936. I felt assured that the Dartmouth theatre collection could bring me up to date from the 1940s with clippings, reviews, and programs on such contemporary performers as Earle Hyman, Jane White, Moses Gunn, Gloria Foster, James Earl Jones, and others. But there was an enormous span of almost seventy years between Aldridge's death in 1867 and Welles's Macbeth. 'Where should the search begin to fill this breach?

Normally, if one were researching professional productions of past times, one would go to published catalogues, newspaper indexes, clippings files in theatre collections,and so on. But in post-bellum America, black actors were not to be found in the regular dramatic theatre (which was of course all white) and certainly not as Shakespeare's heroes and heroines in such productions. That was the reason Aldridge had left these shores in the first place.

Let me offer an example of the problem I faced. In a black publication of the period, I came across a reference to an actor, Hurle Bavardo of Baltimore, whose picture, handsomely costumed as Othello, adorned the front page of the New York Dramatic News andSociety Journal of May 8, 1883. The caption stated: "the only colored, talented and cultivated Shakespearean in America." My heart skipped a beat. "Ah," I thought, "this must be another Aldridge, someone of tremendous talent who, in spite of all obstacles, could be pictured on the front page of a society journal in America!" But when I had tracked down all the information I could on Bavardo, he turned out to be one of the weakest actors of his day. Not only was he outclassed by his black contemporaries, but he suffered from that most dreaded of all histrionic afflictions - a faulty memory. He kept forgetting his lines and relying on the prompter; once when he had a very inexperienced prompter in the box, his performace was so bad that the reviewer thought he should give up acting. Yet this was the single black performer to receive front page billing in a prestigious white publication.

I still hadn't got very far in filling the gap between Aldridge and Robeson, and I realized that there was no time, prior to my lecture date, to begin the systematic perusal of old black newspapers and journals, many on microfilm, which would have to be done some day to complete the record. I managed to spend a few days at the Library of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and at the Schomburg Center for Black Culture in Harlem making some spot , checks, hopeful I would turn up something. Lincoln Center had a prompt copy of Robeson's London production of Othello back in 1930, with striking photographs of him and the winsome Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona. The Schomburg Library was pretty depressing. It had not yet moved into its handsome new building on Seventh Avenue and files were in a fairly chaotic state. But I did find a couple of nuggets among the rubble. There was, for-instance, a little book of Richard III, published in 1887 and edited by J. A. Arneaux who aimed "to smooth the rough edges of Shakespeare" and to render the play "suitable for the drawing-room as well as the stage." How anyone could mount a production of Richard III in a drawing-room still confounds me. The play has several crowd scenes, a funeral procession, a prison cell, two tents, half-a-dozen ghosts, and a pitched battle during which Richard enters crying the famous lines "A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse." What really caught my attention in Arneaux's version of the play was the by-line "as played by him at the Lexington Opera House, New York, 1886 and reproduced at the Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 1887." Moreover, there was a picture of the editor at the end of the book. With this lead I was able to trace Arneaux's career as an actor and producer of Shakespeare with an all-black company in the 1880s.

Arneaux's arrogance in being the first black to publish an edited version of a play of Shakespeare (which of course white editors have been doing for centuries) did not escape censure. The critic for The New York DramaticNews was simply outraged. "Ye Gods!" he exclaimed, "Imagine a colored gentleman hailing from the classic region of Sullivan Street 'smoothing the rough edges of Shakespeare.' I wonder if Mr. Arneaux used a razor on the text."

The other piece of information I gleaned on my visit to the Schomburg was that in 1916, to mark the three hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare's death, one Edward Sterling Wright, a Boston native attached to the New York City Board of Education, acted Othello at the famed Lafayette Theatre in Harlem. It too had an allblack cast. Now, as we know, the play is predicated on the situation of a black general, surrounded by a white society and white junior officers, marrying a white Venetian girl. Hence the following comment by one reviewer:

The audience wondered a little at first how they were going to recognize Othello when he made his appearance. As it turned out there was no difficulty. Mr. Wright's make-up as the Moor was as unmistakable as Sir Henry Irving's or Salvini's or Sothern's. [These were great Shakespearean actors of recent date.]

And the reviewer concluded that, in fact, Mr. Wright may have come nearer to the ideal that Shakespeare had when he created the part than a good many distinguished actors had done.

Well, I was getting near my goal. It looked as if I would make deadline for the lecture and be able to present a somewhat consistent if admittedly sketchy record of black Shakespeareans from the early 1800s up to our time. I had Aldridge, Arneaux, Bavardo (God help us all), Wright, the "Voodoo" Macbeth, and two Othellos of Robeson on which to lay foundation for the work of contemporary actors. There was just one final source I had to double-check before composing my lecture.

In the days when college professors were suppposed to be professors and not committee members, when they had the leisure to pursue eccentric scholarly pursuits over an extended period of time without the Damoclean sword of "publish or perish" hanging over their heads, a professor of dramatic literature at Columbia University named George C.D. Odell began to assemble and publish a complete record of 19th-century theatricals in New York City. Nothing escaped his notice. He culled items from playbills, programs and pamphlets, he scanned newspapers, journals, broadsides of all descriptions and colors. Calling his work Annals of the New York Stage, Odell published fifteen big volumes of invaluable information over the years 1927 to 1949. He was, I believe, the first scholar to trace the activities of that remarkable little band of black Americans in lower New York who were known as the African Company and who began performing Shakespeare in 1821 with their star actor, James Hewlett. Odell even provided a picture of Hewlett as Richard III. The youthful Aldridge was a member of this company before embarking for England.

Odell records that the New York police eventually stopped the African Company from playing Shakespeare, whether because of rowdy elements and out of repsect for the Bard, as alleged, or because the Company had moved uptown to give the prestigious Park Theatre a run for its money, I leave you to judge when you read my book. Among other intriguing historical intelligences noted by Odell are the earliest attempts at Negro minstrelsy (which as we know came to dominate the 19th-century popular stage), the existence of several colored professional and amateur groups, and what must be the rarest of all notices, an Othello performed in 1893 at the Bijou Theatre in New York by the pupils of Charles J. Fletcher, with Fletcher himself playing lago and Lillian Russell's ex-coachman, a Native American named Tacatantee, as Othello.

My lecture, enlivened by slides, was dutifully delivered at the Pratt Institute on April 20, 1977. I was told it went well. I should have been content to let it rest there for I had other writing projects in reserve and needed to get back to them. Instead, I sent the 35-page manuscript to the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., to see if they might be interested in printing it as a booklet. They were not. I then gave the manuscript to a friend in a small publishing firm who was excited about it and strongly encouraged me to develop it into a modest monograph with a promise of publication when it was completed. By this time I knew, of course, that I was merely temporizing. There was no way I could escape doing what had to be done.

Work on the manuscript started in earnest. I put aside other projects to concentrate on this one. I began reading the black newspapers in microfilm, and tedious as that was (Oh, for some graduate students to assign to such tasks!), it was richly rewarding. Colleagues around the country heard of my endeavor and began to send me leads. A woman in London who was researching the same period as I but on a different topic, regularly sent me a list of references to another black thespian, Samuel Morgan Smith of Philadelphia, who had gone to England after Aldridge and acted Shakespeare there for thirteen years. I learned about Henrietta Vinton Davis, an exquisite Shakespearean reader and Marcus Garvey activist, who was in the acting business for some 30 years but never got the chance to perform Shakespeare in a fully professional company, and of the little shoe-shine boy, Charles Winter Wood, who at age 16 with his own company played Othello and Richard III in a public theatre in Chicago, then went on a scholarship to Beloit College, from which he graduated with a major in Greek and became a college professor at Tuskegee Institute.

Some three years later, I had a manuscript of over 200 pages containing a good deal of original material, a foreword graciously contributed by the celebrated actor and Shakespearean producer John Houseman, and above all, acceptance by the same press. I breathed a sigh of relief and satisfaction. When summer arrived, I took off for a vacation and returned home to enormous disappointment. The small press that was to publish my book had found itself in financial distress and was forced to suspend all new publications. I was, to put it mildly, devastated.

It would take two more years of searching for a new publisher, reading some harsh (and well-deserved) readers' reports, and undertaking a complete rewriting which entailed adding another hundred pages of new material before the manuscript was finally accepted by the University of Massachusetts Press. It was worth waiting for. The Press produced an elegant volume that recognizes the long and distinguished record of Afro-Americans in the most glorious challenge of the actor's art, performing those magnificent roles of the immortal Shakespeare.

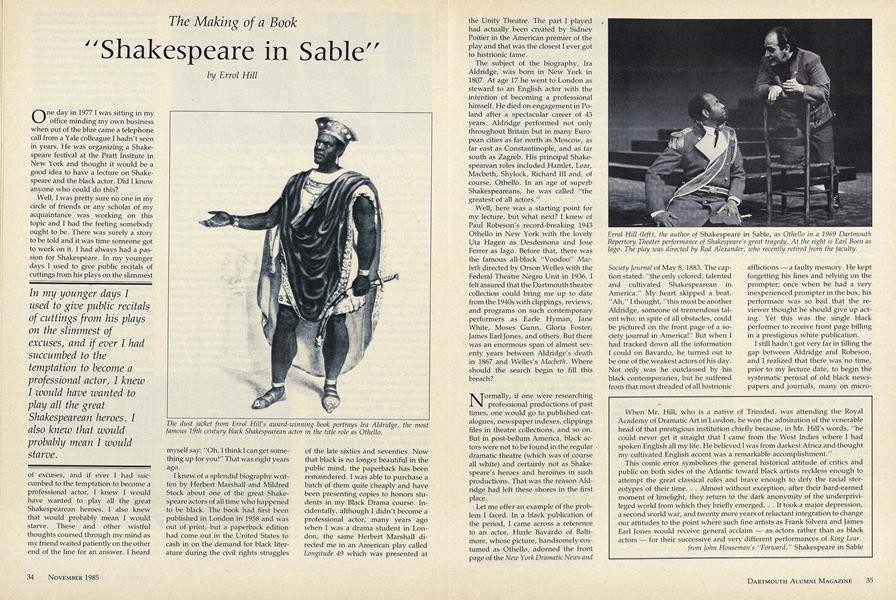

The dust jacket from Errol Hill's award-winning book portrays Ira Aldridge, the mostfamous 19th century black Shakespearean actor in the title role as Othello.

Errol Hill (left), the author of Shakespeare in Sable, as Othello in a 1969 DartmouthRepertory Theater performance of Shakespeare's great tragedy.. At the right is Earl Boen aslago. The play was directed by Rod Alexander, who recently retired from the faculty.

Ruby Dee as Kate makes her point felt with Petruchio (John Cunningham '54) in thisAmerican Shakespeare Festival Theatre production of the Bard's Taming of the Shrew.

In my younger days Iused to give public recitalsof cuttings from his playson the slimmest ofexcuses, and if ever I hadsuccumbed to thetemptation to become aprofessional actor, I knewI would have wanted toplay all the greatShakespearean heroes. Ialso knew that wouldprobably mean I wouldstarve.

When Mr. Hill, who is a native of Trinidad, was attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, he won the admiration of the venerable head of that prestigious institution chiefly because, in Mr. Hill's words, "he could never get it straight that I came from the West Indies where I had spoken English all my life. He believed I was from darkest Africa and thought my cultivated English accent was a remarkable accomplishment." This comic error symbolizes the general historical attitude of critics and public on both sides of the Atlantic toward black artists reckless enough to attempt the great classical roles and brave enough to defy the racial stereotypes of their time. . . Almost without exception, after their hard-earned moment of limelight, they return to the dark anonymity of the underprivileged world from which they briefly emerged. . . It took a major depression, a second world war, and twenty more years of reluctant integration to change our attitudes to the point where such fine artists as Frank Silvera and James Earl Jones would receive general acclaim - as actors rather than as black actors - for their successive and very different performances of King Lear.from John Houseman's "Forward," Shakespeare in Sable

... the New York policeeventually stopped theAfrican Company fromplaying Shakespeare,whether because of rowdyelements and out ofrespect for the Bard, asalleged, or because theCompany had moveduptown to give theprestigious Park Theatre arun for its money, I leaveyou to judge . . .

My earliest recollection of performing was at morning prayers held by my mother on weekdays. Because we all went to church several times on Sunday we escaped the early morning ritual on that day - except on a feast day like Easter Sunday when mass was held at 5:00 a.m. and we had to rise earlier than usual. All the children would gather at my mother's bedside and would read one or two chapters from the Bible, sing a hymn, and say a prayer. We took turns at reading, and 1 recall how anxiously I awaited my turn and secretly practiced reading the chapter beforehand so that I would make a good impression on the family. The Scriptures and Methodist hymns were the first literature I knew. Dramatic story and Shakespeare came later in the upper grades of elementary school. I was fortunate to have a gifted teacher, himself a novelist with a flair for language, who read poetry as if it had wings on which one could soar. From that time on I have never ceased to memorize pieces of beautiful prose and poetry so that I too might give them winged utterance. from Errol G. Hill's "Introduction: A Personal Memoir," Shakespeare in Sable

The small press that was'to publish my book hadfound itself in financialdistress and was forced tosuspend all newpublication. I was, to putit mildly, devastated.

[This article was presented in slightly different fortn at the Book and Author Luncheon of the Friends of Hopkins Center in1984, and later, at a book party sponsoredby the American Shakespeare Theatre. Theauthor is the Willard Professor of Dramaand Oratory at Dartmouth. His book, Shakespeare in Sable: A History of Black Shakespearean Actors (Univ. ofMassachusetts Press, 1984), was selectedby Choice as "one of the outstanding academic books of 1984." Ed.]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

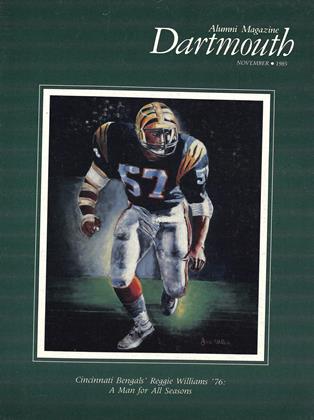

Cover StoryA Man for All Seasons

November 1985 By Douglas McCreary Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeaturePolitics in an electronic age

November 1985 By Jim Newton '85 -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

November 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1985 By Catherine A. Gates -

Sports

SportsTough days on the gridiron

November 1985 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1985 By Bruce D. Jolly

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWOOD AND CANVAS CANOE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

JULY 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14 -

Feature

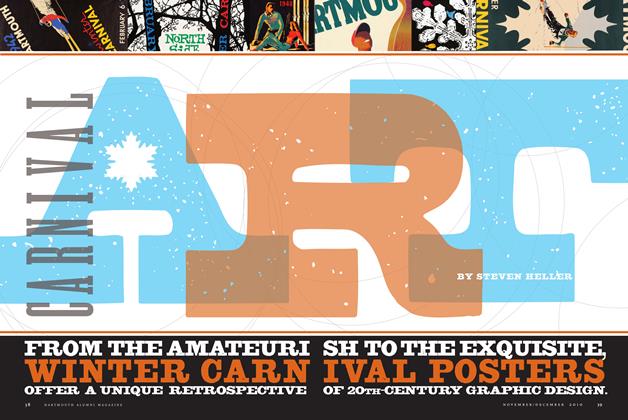

FeatureCarnival Art

Nov/Dec 2010 By STEVEN HELLER -

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat