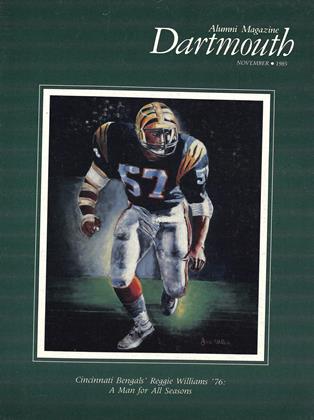

Reggie Williams: The Spirit of '76

What can you say about one of the most gifted and surely the most honored football player Dartmouth has produced since Bob MacLeod '38

- that he was an all-American selection his senior year, a three-time all-Ivy selection, a guy who made every all-East, all-New England team two years in a row; that he won the Earl Hamilton Award as a freshman, the Alfred Watson Trophy as Dartmouth's outstanding athlete his junior year, the Jake Crouthamel Award as a junior and the Bob Blackman Trophy as a senior; that he led the team in tackles for three straight seasons; that he was also outstanding as a wrestler (all-Ivy, team captain, holder of the College record for the fastest pin, 16 seconds); that he graduated from Dartmouth in three-and-a-half years as a psychology major. You could say all of those things and they'd all be true. Or you could quote former Harvard coach Joe Restic: "Reggie Williams is the best linebacker I've seen this year - live or on film." Or Yale coach Carmen Cozza: "He's by far the best linebacker we've ever faced since I've been at Yale (1963)." Or you could quote Dartmouth physics Professor Joseph D. Harris: "Mr. Williams is an unusually scholarly, serious, and thoughtful student whose work merits special commendation. His joy in learning set a fine example."

Now in his tenth year with the Cincinnati Bengals of the National Football League, Reginald Williams, Class of 1976, hasn't let up at all. If anything, he's done even more to enhance his reputation on the field, with perenially impressive stats in tackles, interceptions, sacks, and fumble recoveries. And as good as he is on the gridiron, Reggie is perhaps even more impressive off the field. Indeed, for the past three years, Williams has been the Bengals' NFL Man-of-the-Year, an award given to the player who on the field and off exhibits leadership and a special concern for the welfare of his community. And this past June he received the Byron R. "Whizzer" White Humanitarian Award from the NFL Players Association.

If you doubt for a moment Reggie's fame, take a walk downtown in Cincinnati. Everywhere you go - and I mean everywhere - it's "Hey, Reggie! How you doing, man." Or "Hi, Reggie. Glad you're coming back this year." (Reggie had contract problems earlier this spring.) A nine- or ten-year-old boy shyly walks up with, "Uh, Mr. Williams, could I have your autograph? And instead of the uninterested "Sure, kid." that some big-time athletes respond with, Reggie will look the youngster in the face and ask, "How are your grades? Do you do your homework every day? Are you going to finish high school and go to college?" - questions that startled more than one boy who merely wanted an autograph.

Whether it's popping unexpected questions or popping fullbacks, Reggie is a study in determination. Yet, as one who has played pro ball for a decade, he knows at the same time that his days as a starter with the Bengals are limited. Like a young pilot on his way to the Front in World War I, the numbers simply aren't in his favor.

That's where the education comes in, and that's where Reggie Williams, who came to Hanover to be a doctor, waxes eloquent about the value of a Dartmouth A.B. "Dartmouth helped me by giving me the background to make it. In pro ball there are lots of unseen costs - it's not all the glory it looks like on TV on Sunday afternoon. There's training, running, learning to sleep on a banged-up shoulder, the things no one sees. Dartmouth provided me with the environment to grow. I was really a mediocre athlete when I came in as a freshman. My teammates had a tradition of pushing us to win. Some guys really didn't have enormous physical size. Tom Csatari '74, for example. He taught me intensity, the will, to win. And you know what kind of player he was.

"And there were others who had a great influence on me at Dartmouth - [Athletic Director] Seaver Peters '54, [Sports Information Director] Jack DeGange, and [Linebacker Coach] Rick Taylor - who really prepared me for the world outside Hanover.

Taylor, who is now Boston University's athletic director, recalled of Reggie, "He's why people get into the [coaching] profession. You watch them mature academically, socially, athletically; and if you're lucky, you get to watch them after college. Reggie's typical of all-that's right about athletics. But it wasn't all roses when he was playing at Dartmouth. He had a bit of an 'attitude,' and I told him, 'We can't win with you the way you are and we can't win without you.' He grew up and our association has blossomed into a friendship."

There were others Reggie singled out - Dean Ralph Manuel '58, who helped Williams through some trying times, and Professor William Slesnick of the mathematics department. "I took Math 3; the first part was easy, but then I got into some bad study habits, spending too much time with football. I went to Slesnick to ask how to get back in stride in his class. He had instant recall of my grades - unfortunately - and helped me out. I ended up doing well in that course because of him. He made me feel that I mattered, that I was getting the very best education.

"I was offered a full scholarship at Michigan, a full ride, even though [coach] Bo Shembechler didn't seem much interested in me. Then I visited Hanover through the Sponsorship Program and went to the banquet celebrating Dartmouth's third straight Ivy championship. That did it. If Dartmouth was going to let me in, I was going to come."

But things weren't always hunkydory dory for Williams. Not by a long shot. For starters, he counts among his alma maters not only Flint [Mich.] Southeastern High School and Dartmouth, but also the Michigan School for the Deaf and Dumb, where as a youngster, Reggie spent some of his most trying days. In retrospect, the chances of a student of MSDD going on to college, let alone to an Ivy institution, and from there on to the playing fields of the NFL must be about the same as for you, gentle reader, or me to ever know what it's like to walk on the moon. What made it all possible, according to Reggie, was his home environment in Flint, where his father, Elijah, worked as a millwright for Fischer Body and his mother, Julia, ran the show at home. Throughout Reggie's primary and secondary school years, they made good grades a top priority. His mother, a voracious reader, encouraged Reggie to do the same. In the end, this habit proved to be the key to Reggie's dramatic escape from what very well might have been a life diametrically opposed to the life he enjoys today.

That story begins with the Williams family's move from a lower income school district to a more affluent, fully- integrated school where his teachers recognized that something was wrong, dreadfully wrong, with this obviously- bright young boy. He lisped badly, he was shy, and he couldn't seem to come up with the right answers in class. Yet he was exceptionally well-read and did well on assignments where no verbal communication was required. A battery of tests revealed a 40-percent hearing loss in both ears, a fact that accounted for much of the difficulty Reggie had in learning to speak clearly. As Reggie very poignantly put it, "Unless you've been there yourself, you can't begin to imagine how even a small handicap can make such a tremendous difference. It's like walking in quicksand."

At the Michigan School for the Deaf and Dumb, Reggie was, by his own admission, lost. He knew he couldn't survive in the public schools, but the environment at a school for the deaf and dumb was even worse - it seemed to be a sort of double humiliation. Aloof at first, refusing to speak to anyone, Reggie felt sorry for himself. After all, the world doesn't look too rosy from the inside of a classroom for the physically impaired. What broke the ice for Williams was - of all things - a cookies and milk session. As Reggie recalled with an impish grin, "I've always been a cookie monster." He also recalled with a more serious tone that of the four or five members of his class, he was the only one to make it back to the public school system. And it was reading that he credits with getting him there.

"The first possession I could call my own was my library card. I would walk down the aisles of the library and pull out books with interesting covers and titles. I read about George Washington Carver and Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, but the black Americans who impressed me most weren't in books, but movies - Paul Robeson and Sidney Poitier. You know, movies appeal to you in a different way, and Lilies of the Field was a milestone for black America and for me in particular. You didn't see him [Poitier] as a black person; he was just playing a role, just an actor."

What was it about reading that fired his imagination? "I always wanted to emulate fictional heroes. Reading on my own, I would grab anything about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War

. . . because America when I was growing up was a winner. The country wore its stripes proudly. There were parades. [ln those books I read] we were fighting for independence, for an end to slavery. I know it's a simplistic view, but I was young and had a very romantic notion of war. I suppose that's why I gravitated to football - it's the closest thing to war without shooting bullets."

There is a pause. "I knew I was different. The peer pressure was very strong [at MSDD], as it always is When you're young. And the fact that I was black made it even more challenging." Gaudet tentamine virtus, the motto of the second Earl of Dartmouth. It might well be emblazoned on the Williams coat of arms. Valor welcomes a challenge. For problems which might have crippled a lesser soul took on a significance which can only be described in retrospect as a curious sort of blessing, carrying Reggie Williams to the highest level of competitive athletics and to fields beyond. Yet he has never forgotten the pain wrought of other people's insensitivity.

"When we were in the Super Bowl in '82, we were making a comeback against the [San Francisco] Forty-Ni-ners. I had made some comments about my speech/hearing handicaps in an interview the week before the Super Bowl. During the game, I made a pretty good hit [tackle], and this TV commentator comes on and says, 'At one time, Reggie Williams was considered retarded, and he went on to become an Ivy League graduate.' A hundred million people listening and that's what he says." And with a smile that is not a happy smile, Reggie wryly remarks, "Dartmouth College has a retarded graduate."

Over the years since graduation, Reggie has changed. In some of the early Bengals publicity shots, he sports a Fu Manchu mustache, a scruffy beard, a fashionable Afro hairdo. Today the image is considerably different. One might call it the quintessential Ivy look - closely cropped hair, no mustache, short sideburns. The "tough" who had to prove he could make it in the big leagues as an outsider from the Ivies is very much a figure of the past. Being an Ivy Leaguer wasn't helped at all by the rookie performance of Bengal teammate Pat Mclnally of Harvard, who, before the season even started, fell down, dislocated his shoulder, and was out for the year. For that they nicknamed the former Crimson all-American "Candle." (As wide receiver Issac Curtis explained, "You go up to Mclnally, and with about the same effort it takes to blow out a candle,, pffff, he's gone for the season.") Mclnally, you may recall, was on the unpleasant end of a vicious (see left) Reggie Williams hit in the 1973 Harvard game. (The Green won, 24-18, and the shot was on the Sept. '75 Alumni Magazine cover.)

It wasn't until Williams left Dartmouth that he had his first negative coaching experience. "I had been invited to the Senior Bowl, the Hula Bowl, and the Japan Bowl. I passed up the first one and went to the Hula Bowl. I had signed on with an agent before the game, but I played so badly that he dropped me after it. They [the coaches] treated me as a second-class citizen and it really hurt. I had to pick up the pieces."

And pick up the pieces he did. Drafted in the third round by the Cincinnati Bengals, Reggie was their sixth pick. This seemed like a good omen to Williams, who had grown fond of combinations of 6 and 3. He had worn the number 63 throughout his Dartmouth career, but when he got to the Bengals training camp, he was assigned number 57. "It was better than no number at all, and I was a rookie, just trying to make the team, so I couldn't complain," he recalled.

The number 57 may be purely coincidental, but the man who runs the day-to-day operations of the Bengals is a former Dartmouth quarterback, Mike Brown, Class of 1957 (and son of famed NFL coach Paul Brown, president and owner of the Cincinnati franchise). Mike had seen Reggie in action against Harvard in the '75 game and he liked what he saw. "Reggie was fast about 4.6 in the 40 - and he weighed about 200. He had the right frame and we thought he could be good. Reggie also had great movement, particularly inside. And more than anything else, he had the right attitude - it's been consistent and it's been great ever since he's been around."

Brown, who is still in the Dartmouth record books, admits, "Instead of being biased against, I'm biased for the Ivy League. What you get from the Ivies is guys with potential. Reggie was a starter for us four games into his rookie season, and, except when he was injured, he's been a starter ever since." Mike also speaks with pride about a couple of family members.

"My daughter Katie's at Dartmouth now. I was a bit dismayed looking at the statistic book she had. It showed that I had the most TD's with the least yardage of any qb in Dartmouth history." And of his father, who had a reputation as a stern disciplinarian from his earliest days as a football coach: "My father had something do to with my going to Dartmouth. He had a pretty good sense of who could coach and who couldn't. He recommended Vince Lombardi to Green Bay and a guy named Blackman for the head position at Dartmouth. When I got up to Hanover I was a bit homesick and I wasn't first, second, or even third string. Dad said, 'You made your choice,' and I stuck it out. I'm glad I did."

The Bengals locker room at Spinney Field in downtown Cincinnati is a strangely quiet place this June morning. There are wire cages variously littered with sweatshirts, shorts, pads, sneakers, helmets - all manner of gladitorial odds and ends. Kenny Anderson shakes my hand as I walk in to the inner sanctum. He looks smaller than I had imagined. I think of the many times I have seen a linebacker grab him and fling him to the ground like a rag doll and I wonder how he has survived this vicious game. On the hard cement floor is a garish orange-and black-striped rug. In the adjoining weight room, the few men who are there come and go talking quietly among themselves. It is in these chambers that they will mold their bodies into shapes most of us only dream of. The room itself, filled with ugly machines that countenance weights and chains and tubular rods, looks something like a cross between a Buck Rogers torture chamber and a parts warehouse for used cars. It is BraveNew World in miniature, "humanized" by incongruously bizarre posters of John Wayne, Ray Charles, Bogart, Marilyn Monroe, John Belushi, Charles Bronson. A juke box at the back of the cramped room plays songs from the sixties and seventies.

"You want to work out with me?" Reggie asks. I think of all the reasons why I can't. I'm afraid to use the line I usually do on such occasions - "Whenever I feel the need to work out, I lie down and sleep it off." I've got a much better excuse. "Geez, Reggie, I forgot my sneakers. I think I'll just mosey around and take some notes." Reggie looks down at my size 7½ feet and smiles. There are no 7½ sneakers around this place.

From a forbidding Nautilus machine comes the curious, rhythmic whine of a chain running along gear sprockets. The sound, something like a cheap, noisy curtain being opened again and again, is unexpectedly punctuated by an agonized grunt. It is an echo of what natural childbirth - or at least prolonged labor - must sound like, full of pain and exhaustion and desire. Reggie finishes his leg lifts and then, like Jim Brown getting up after he has been tackled, he moves deliberately on to the next instrument of torture. Ten minutes into the half-hour workout, Reggie is sweating profusely. "This isn't quantity time," he says, "it's quality time." The Nautilus concept, which involves working on a group of muscles, has obvious tangible benefits. At Dartmouth, Reggie had a fine physique, but there had been little more than weight-lifting and strength exercises. Today, after ten years of Nautilus training, he looks like the incarnation of one of Michelangelo's man-gods.

The Bengals' strength coach, Kim Wood, pops his head in, stares, and demands, "Who the hell are you?" Reggie intercedes. "It's okay, Kim, he's with me. He's doing a piece for the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine." And then, with the spontaneity of an alumnus rising to the strains of "Glory to Dartmouth," Wood starts belting out "As the Backs Go Tearing By." Reggie laughs and turns back to work. I look around, amazed. I am 900 miles from Hanover in a cold concrete bunker and there is music in my mind and ears Dartmouth music.

I introduce myself. "Class of '66. What class are you?" "I wish I'd gone to Dartmouth," Kim says. "I had the grades, played some ball myself, but I ended up at Wisconsin. The reason I know all the Dartmouth songs is my dad, George, he's a '36. In fact, he's planning to canoe down the Connecticut for his 50th next June. That's Dartmouth for ya. . . So you're writing a story on Reggie. He's one helluva man. A real credit to your school, a wonderful person in every way. He's the best-conditioned man on the team. And he's no phoney PR man, either. He can walk into any company in town

- Proctor & Gamble, GE - and talk to the president. He's well-liked and well-respected in all quarters here." Reggie's skin is glistening, his grey T-shirt completely soaked.

Isaac Curtis - "Ice" as in "smooth as ice" to his teammates - has just finished his laps. He sits down next to me to talk about Reggie. "We've been close for years. When he got hurt, he came out to California and stayed with me for the- year rehabbing his knee. I don't think there was any doubt in his mind about his making it back. I know there wasn't any doubt in mine. He's a hard worker." We talk about retirement. He and Kenny Anderson and Reggie are among the old-timers. Ice thinks this may be his last year. And though he doesn't know it yet, he won't be suiting up on Sundays this fall. Time has caught up with him and he will retire.

At home, the environment contrasts sharply with the spartan, dank atmosphere of Spinney Field. Marianna, the woman who has put her own-career as a fashion designer on hold until Reggie retires from the gridiron wars, is as articulate as she is attractive. She endures the screams, messes, and squabbles of their two boys, Julien (nearly 3) and Jarren (a year younger), with an air of easy acceptance, knowing that it won't always be this way. Reggie's arrival, even though he has been gone only a few hours, is a major event. "Daddy, Daddy, Daddy!" echoes through the large hallway opening into the living room as the boys run precariously toward their father and jump up into his massive arms.

There have been several phone calls today. Reggie's active involvement with numerous civic groups - the American Cancer Society, the Cincinnati Cerebral Palsy Telethon, the Cincinnati Speech and Hearing Center, Big Brothers/Big Sisters to cite a few - is the reason for a couple of the calls. In the off-season, these activities take a lion's share of his time. Another organization particularly close to his heart, the Reggie Williams Scholarship Fund, annually awards scholarships to outstanding students in each of Cincinnati's nine public high schools. On the occasion of the "Whizzer" White Award, The Cincinnati Enquirer editorialized: "Football giants like Reggie Williams have dazzling careers and face dazzling temptations - adulation, celebration, and more money than they ever dreamed of. . . It's not surprising that many succumb to the temptations and shatter their careers and themselves. Reggie Williams sees his success as a tool to help others. Cincinnati is enriched in many ways by his presence." Another day in the life of Reggie Williams.

Downstairs, the walls are fairly littered with the awards, plaques, and memorabilia Williams has amassed in his athletic career. Among the items which stand out is a Norman Rockwell poster of a little black girl being escorted into an Alabama classroom by federal marshals. It is a reminder of the recurrent evils of racism; a reminder, too, of how far the country has come since the landmark decision of Brown vs. the Board of Education.

Back upstairs in his study, Reggie is very much at home sitting at a large wooden desk. He is already an executive with a chemical company and the experience he has had in addressing civic, social, and educational groups has given him an unmistakable air of quiet self-confidence. Behind him are shelves and shelves of books about Japan, Hawaii, Hong Kong, Michelangelo, the Mideast. Everywhere are mementoes of Dartmouth: the football program for the 1924 Dartmouth-Harvard game (which he bought last winter at a Dartmouth club dinner in Dallas); a Dartmouth captain's chair; his Dartmouth helmet (which the College made him buy); books about the Ivy League and the College on the Hill. On the wall are two diplomas (his from Dartmouth and Marianna's from the University of Cincinnati), a huge color photograph of Marianna that Reggie took (he's quite an amateur photographer), and a poster of Mexico City. "I didn't get Montezuma's revenge," Reggie smiles, "though there was a time when that would have seemed mild to what I was going through. I wasn't the world's greatest Spanish student and I still lisped pretty badly. But it wound up being one of the turning points of my life - I knew I was truly on my own down there.

"In four years - three and a half, actually - I made a quantum leap; all the nutrients for my growth were there. The cornerstone for my success in the NFL was my Dartmouth degree - because whatever else they could do to me, no one could take that away. "That's not to suggest that it wasn't difficult for me at Dartmouth. There weren't a lot of blacks, there wasn't much of a social scene, and there certainly weren't many black professors or administrators. But it was a very positive experience for me in spite of these facts. My heroes might surprise you - Paul Brown, my father, Martin Luther King, Richard Nixon (this guy has rebounded from perils that make my problems look miniscule), and lots of people who don't have long resumes or permanent places in society, the rookies who've worked incredibly hard, yet haven't made the team. I guess it all boils down to sensitizing people to other people. It needs to be done, as simple as it is. The little things

- like opening the door. That's part of what Dartmouth taught me - etiquette, an ability to speak out for what I believe in, fighting for the best traditions, sportsmanship, respect for every person's endeavor."

Respect. That's what it's all about. Amen, brother.

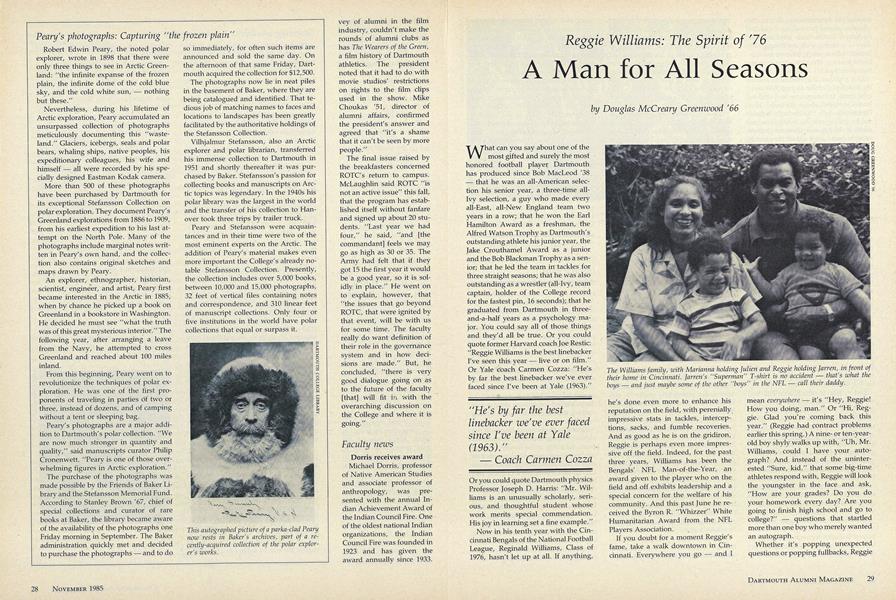

The Williams family, with Marianna holding Julien and Reggie holding Jarren, in front oftheir home in Cincinnati. Jarren's "Superman" T-shirt is no accident - that's what theboys - and just maybe some of the other "boys" in the NFL - call their daddy.

Former Harvard ail-American Pat Mclnally remembers this collision with former Dartmouthall-American Reggie Williams in the '73 Harvard-Dartmouth game. Now teammates onthe Cincinnati Bengals, Mclnally is glad to keep it that way.

Former Dartmouth quarterback Mike Brown '57 and Reggie share a light moment at Riverfront Stadium, where Mike's in the front office. It may be purely coincidental, but Reggie,who wore number 63 all the way through Dartmouth, now wears number 57.

Bengals hard-hitting safety Bobby Kemp and Reggie take a breather at Spinney Field.

"He's by far the bestlinebacker we've ever facedsince I've been at Yale(1963)." - Coach Carmen Cozza

"I visited Hanover through the Sponsorship Programand went to the banquet celebrating Dartmouth's thirdstraight Ivy championship. That did it. If Dartmouthwas going to let me in, I was going to come."

"The first possession Icould call my own was mylibrary card. "

The "tough" who had toprove he could make it inthe big leagues as anoutsider from the Ivies isvery much a figure of thepast.

Today, after ten years ofNautilus training, helooks like the incarnationof one of Michelangelo'sman-gods.

"The cornerstone for mysuccess in the NFL wasmy Dartmouth degree - because whatever else theycould do to me, no onecould take that away."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Shakespeare in Sable"

November 1985 By Errol Hill -

Feature

FeaturePolitics in an electronic age

November 1985 By Jim Newton '85 -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

November 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1985 By Catherine A. Gates -

Sports

SportsTough days on the gridiron

November 1985 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1985 By Bruce D. Jolly

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

DEC. 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Responsibilities of Management

March 1956 By J. IRWIN MILLER -

Feature

FeatureHow Does It Feel?

Jan/Feb 2010 By LEANNE MIRANDILLA ’10 -

Feature

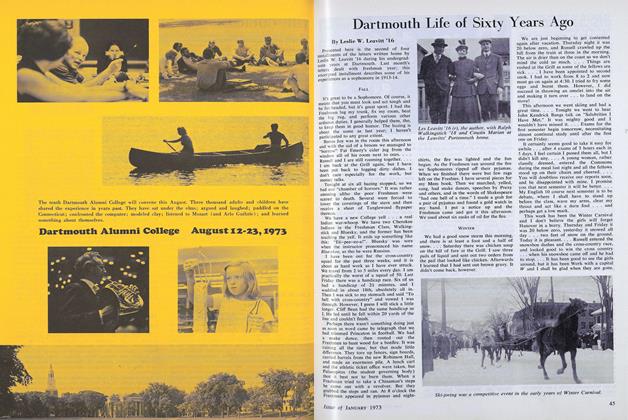

FeatureDartmouth Life of Sixty Years Ago

JANUARY 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79