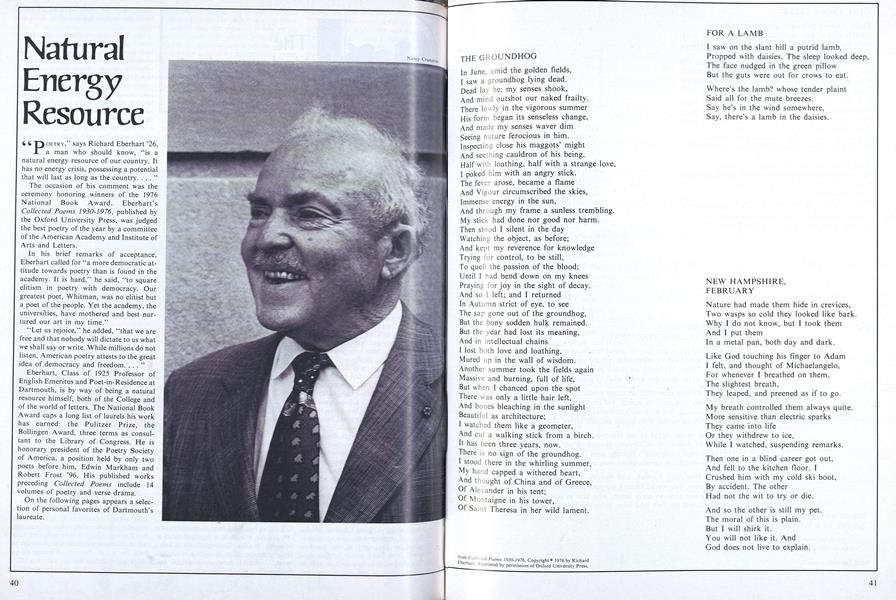

"POETRY," says Richard Eberhart '26, a man who should know, "is a natural energy resource of our country. It has no energy crisis, possessing a potential that will last as long as the country...."

The occasion of his comment was the ceremony honoring winners of the 1976 National Book Award. Eberhart's Collected Poems 1930-1976, published by the Oxford University Press, was judged the best poetry of the year by a committee of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

In his brief remarks of acceptance, Eberhart called for "a more democratic attitude towards poetry than is found in the academy. It is hard," he said, "to square elitism in poetry with democracy. Our greatest poet, Whitman, was no elitist but a poet of the people. Yet the academy, the universities, have mothered and best nurtured our art in my time."

"Let us rejoice," he added, "that we are free and that nobody will dictate to us what we shall say or write. While millions do not listen, American poetry attests to the great idea of democracy and freedom...."

Eberhart, Class of 1925 Professor of English Emeritus and Poet-in-Residence at Dartmouth, is by way of being a natural resource himself, both of the College and of the world of letters. The National Book Award caps a long list of laurels his work has earned: the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Award, three terms as consultant to the Library of Congress. He is honorary president of the Poetry Society of America, a position held by only two poets before him, Edwin Markham and Robert Frost '96. His published works preceding Collected Poems include 14 volumes of poetry and verse drama.

On the following pages appears a selection of personal favorites of Dartmouth's laureate.

THE GROUNDHOG

In June, amid the golden fields, I saw a groundhog lying dead. Dead lay he; my senses shook, And mind outshot our naked frailty. There lowly in the vigorous summer His form began its senseless change, And made my senses waver dim Seeing nature ferocious in him. Inspecting close his maggots' might And seething cauldron of his being, Half with loathing, half with a strange love, I poked him with an angry stick. The fever arose, became a flame And Vigour circumscribed the skies, Immense energy in the sun, And through my frame a sunless trembling. My stick had done nor good nor harm. Then stood I silent in the day Watching the object, as before; And kept my reverence for knowledge Trying for control, to be still, To quell the passion of the blood; Until I had bend down on my knees Praying for joy in the sight of decay. And so I left; and I returned In Autumn strict of eye, to see The sap gone out of the groundhog, But the bony sodden hulk remained. But the year had lost its meaning, And in intellectual chains I lost both love and loathing, Mured up in the wall of wisdom. Another summer took the fields again Massive and burning, full of life, But when I chanced upon the spot There was only a little hair left, And bones bleaching in the sunlight Beautiful as architecture; I watched them like a geometer, And cut a walking stick from a birch. It has been three years, now. There is no sign of the groundhog. I stood there in the whirling summer, My hand capped a withered heart, And thought of China and of Greece, Of Alexander in his tent; Of Montaigne in his tower, Of Saint Theresa in her wild lament.

FOR A LAMB

I saw on the slant hill a putrid lamb, Propped with daisies. The sleep looked deep, The face nudged in the green pillow But the guts were out for crows to eat.

Where's the lamb? whose tender plaint Said all for the mute breezes. Say he's in the wind somewhere, Say, there's a lamb in the daisies.

NEW HAMPSHIRE, FEBRUARY

Nature had made them hide in crevices, Two wasps so cold they looked like bark. Why I do not know, but I took them And I put them In a metal pan, both day and dark.

Like God touching his finger to Adam I felt, and thought of Michaelangelo, For whenever I breathed on them, The slightest breath, They leaped, and preened as if to go.

My breath controlled them always quite. More sensitive than electric sparks They came into life Or they withdrew to ice, While I watched, suspending remarks.

Then one in a blind career got out, And fell to the kitchen floor. I Crushed him with my cold ski boot, By accident. The other Had not the wit to try or die.

And so the other is still my pet. The moral of this is plain. But I will shirk it. You will not like it. And God does not live to explain.

THE CANCER CELLS

Today I saw a picture of the cancer cells, Sinister shapes with menacing attitudes. They had outgrown their test-tube and advanced, Sinister shapes with menacing attitudes, Into a world beyond, a virulent laughing gang. They looked like art itself, like the artist's mind, Powerful shaker, and the taker of new forms. Some are revulsed to see these spiky shapes; It is the world of the future too come to. Nothing could be more vivid than their language, Lethal, sparkling and irregular stars, The murderous design of the universe, The hectic dance of the passionate cancer cells. O just phenomena to the calculating eye, Originals of imagination. I flew With them in a piled exuberance of time, My own malignance in their racy, beautiful gestures Quick and lean: and in their riot too I saw the stance of the artist's make, The fixed form in the massive fluxion.

I think Leonardo would have in his disinterest Enjoyed them precisely with a sharp pencil.

THE FURY OF AERIAL BOMBARDMENT

You would think the fury of aerial bombardment Would rouse God to relent; the infinite spaces Are still silent. He looks on shock-pried faces. History, even, does not know what is meant.

You would feel that after so many centuries God would give man to repent; yet he can kill As Cain could, but with multitudinous will, No farther advanced than in his ancient furies.

Was man made stupid to see his own stupidity? Is God by definition indifferent, beyond us all? Is the eternal truth man's fighting soul Wherein the Beast ravens in its own avidity?

Of Van Wettering I speak, and Averill, Names on a list, whose faces I do not recall But they are gone to early death, who late in school Distinguished the belt feed lever from the belt holding pawl.

'GO TO THE SHINE THAT'S ON A TREE'

Go to the shine that's on a tree When dawn has laved with liquid light With luminous light the nighted tree And take that glory without fight.

Go to the song that's in a bird When he has seen the glistening tree, That glorious tree the bird has heard Give praise for its felicity.

Then go to the earth and touch it keen. Be tree and bird, be wide aware Be wild aware of light unseen, And unheard song along the air.

THE HORSE CHESTNUT TREE

Boys in sporadic but tenacious droves Come with sticks, as certainly as Autumn, To assault the great horse chestnut tree.

There is a law governs their lawlessness. Desire is in them for a shining amulet And the best are those that are highest up.

They will not pick them easily from the ground. With shrill arms they fling to the higher branches, To hurry the work of nature for their pleasure.

I have seen them trooping down the street Their pockets stuffed with chestnuts shucked, unshucked. It is only evening keeps them from their wish.

Sometimes I run out in a kind of rage To chase the boys away: I catch an arm, Maybe, and laugh to think of being the lawgiver.

I was once such a young sprout myself And fingered in my pocket the prize and trophy. But still I moralize upon the day

And see that we, outlaws on God's property, Fling out imagination beyond the skies, Wishing a tangible good from the unknown.

And likewise death will drive us from the scene With the great flowering world unbroken yet, Which we held in idea, a little handful.

'IF I COULD ONLY LIVE AT THE PITCH THAT IS NEAR MADNESS'

If I could only live at the pitch that is near madness When everything is as it was in my childhood Violent, vivid, and of infinite possibility: That the sun and the moon broke over my head.

Then I cast time out of the trees and fields, Then I stood immaculate in the EgO; Then I eyed the world with all delight, Reality was the perfection of my sight.

And time has big handles on the hands, Fields and trees a way of being themselves. I saw battalions of the race of mankind Standing stolid, demanding a moral answer.

I gave the moral answer and I died And into a realm of complexity came Where nothing is possible but necessity And the truth wailing there like a red babe.

ON A SQUIRREL CROSSING THE ROAD IN AUTUMN, IN NEW ENGLAND

It is what he does not know, Crossing the road under the elm trees, About the mechanism of my car, About the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, About Mozart, India, Arcturus,

That wins my praise. I engage At once in whirling squirrel-praise.

He obeys the orders of nature Without knowing them. It is what he does not know That makes him beautiful. Such a knot of little purposeful nature!

I who can see him as he cannot see himself Repose in the ignorance that is his blessing.

It is what man does not know of God Composes the visible poem of the world.

... Just missed him!

from Collected Poems 1930-1976. Copyright® 1976 by Richard Eberhart. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

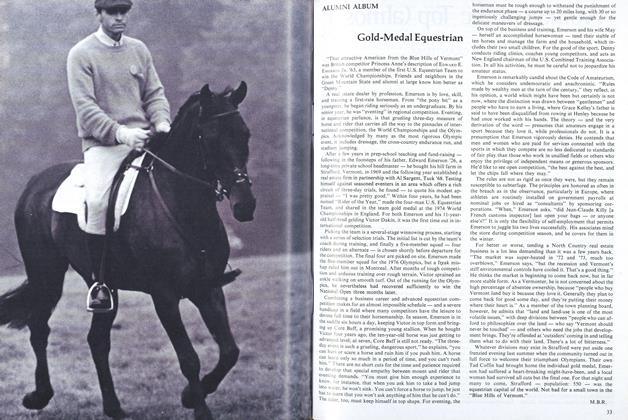

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

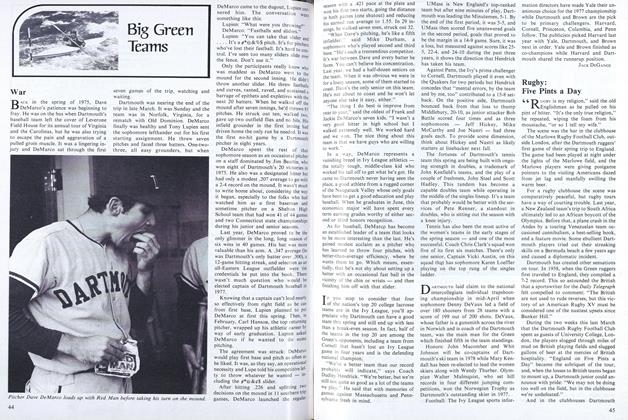

ArticleWar

May 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Books

BooksNotes on justice finally done and old tales long in the telling.

May 1977 By R.H.R. '38

Features

-

Feature

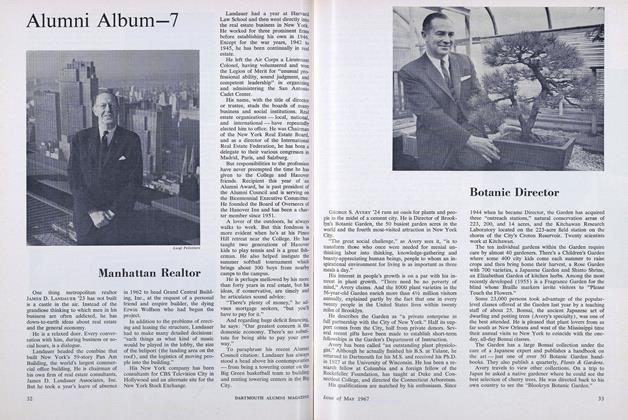

FeatureBotanic Director

MAY 1967 -

Feature

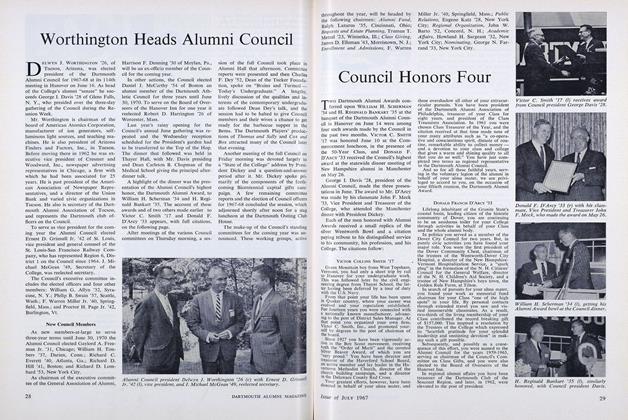

FeatureWorthington Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1967 -

Feature

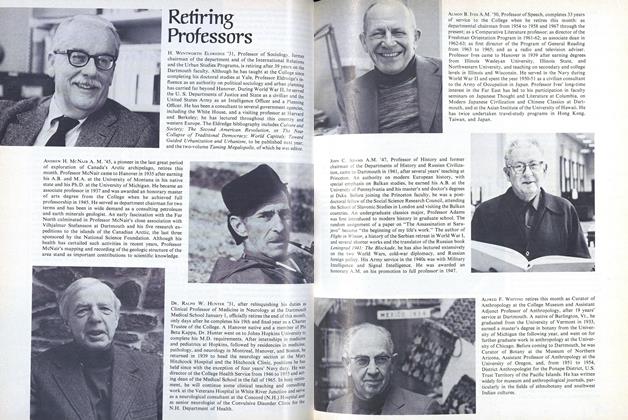

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Find Your Inner Santa

Sept/Oct 2001 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. ’37 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMiraculously Builded In Our Hearts

MARCH 1991 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R.