THE practical workings of the preceptorial system, introduced at Princeton University this year, are being watched with the greatest interest from many colleges. The question is asked, will the innovation give the results which its sponsors promise? The BI-MONTHLY elsewhere offers its readers an article on this subject by Mr. Gerould '99, which answers many of the queries frequently heard. Mr. Gerould speaks with an acquain-tanceship with the Oxford system of tutors, through his two years of study at Oxford. In this connection there will be special interest in the article also published this month, from Mr. Brown '02, New Hampshire Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. The words of President Wilson, whose initiative has put the system into working form, are herewith given, taken from his recent report to the trustees:

A year ago, when I submitted my last report to you, I did not venture even to hope that I was so soon to be able to set about reforms which for more than twelve years past have seemed to me the only effectual means of making university instruction the helpful and efficient thing it should be. I have now the great happiness of realizing that these reforms have already been effected with ease and enthusiasm, that Princeton is likely to be privileged to show how, even in a great university, the close and intimate contact of pupil and teacher may, even in the midst of the modern variety of studies, be restored and maintained. Our object in so largely recruiting our faculty has been to take our instruction as much as possible out of the formal class-rooms and get it into the lives of the under-graduates, depending less on lectures and written tests and more on personal conference and intimate counsel. Our preceptors, with a very few exceptions, devote themselves exclusively to private conference with the men under their charge, upon the reading they are expected to do in their several courses. The new appointments have not been made in the laboratory departments; where direct personal contact between teacher and pupil has long been a matter-of-course method of instruction, but in what may be called the "reading" departments. We are trying to get away from the idea,, born of the old system of lectures and quizzes, that a course in any subject consists of a particular teacher's lectures or the conning of a particular text-book, and to act upon the very different idea that a course is a subject of study to be got up by as thorough and extensive reading as possible outside the class-room; that the class-room is merely a place of test and review, and that lectures, no matter how authoritative the lecturer, are no more than a means of directing, broadening, illuminating, or supplementing the student's reading.

Accordingly, the function of the preceptor is that of guide, philosopher, and friend. In each department of study each undergraduate who chooses the department, or who is pursuing all the courses offered in it in his year, is assigned to a preceptor, to whom he reports and with whom he confers upon all of his reading in those courses. We try to limit the number of men assigned to one preceptor so that they may not be too numerous to receive individual attention. He meets them at frequent intervals, singly or in small groups, usually in his own private study or in some one of the smaller and quieter rooms of the university, and uses any method that seems to him most suitable to the individuals he is dealing with in endeavoring to give their work thoroughness and breadth; and the work they do with him is not of the character of mere preparation for examinations or mere drill in the rudiments of the subject, but is based upon books chosen as carefully as possible for the purpose of enabling them to cover their subjects intelligently.

And the gentlemen I have named are not the only preceptors. We are all preceptors. Under the new course of study the undergraduates choose not only a department with all of its courses, but also a few other electives which they follow without attempting all the courses of the departments to which those electives belong. The lecturers who conduct the courses thus singly or separately chosen, themselves act as preceptors for these students, members of their classes but not of their departments, in respect of the reading that must be done in those subjects; and our new method is making its hold good upon all of us.

One way of stating the nature of the change is to say that now the reading of subjects is the real work of the university and not intermittent study for examinations: that the term work, as we have been accustomed to call it, stands out as the whole duty of the student; and the amount of work done by the undergraduates has increased amazingly. But this is a much too formal way of stating the change. It looks at its surface and not within it. It is not the amount of work done that pleases us so much as its character and the willingness and zest with which it is undertaken. The greater subjects of study pursued at a university, those which constitute the elements of a well-considered course of undergraduate training, are of course intrinsically interesting; but the trouble has been that the under-graduates did not find it out. They did tasks, they did not pursue interests. Our pleasure in observing the change that has come about by reason of our new methods of instruction comes from seeing the manifest increase of willingness and interest with which the undergraduates now pursue their studies. The new system has been in operation but a little more than two months, and yet it has affected the habits of the university almost as much as if it were an ancient institution. The undergraduates have welcomed it most cordially and have fallen in with it with singular ease and comprehension, and we feel that both authority and opinion are working together towards a common end, —the rejuvenation of study.

The introduction of a method so unique in America, in a university such as Princeton, merits careful consideration at all our colleges and universities. Manifestly some defect in things as they are is seen, or some large gain over present conditions is expected. It is practically stated that the present system of instruction is considered inadequate, in that there is too little contact between teacher and student. This may be the fault of the instructors in some cases, and in others it may be due to the necessity of instructing divisions so large that the instruction must be given mechanically. The indictment, however, stands ana is justified. There are few institutions, if any, where the multiform calls for available funds do not result in the requirement being laid upon certain departments to handle too many students with too few instructors. Personal knowledge of men or their work under such conditions is hot possible. If this is the only trouble, the remedy seems plain —an increase of funds sufficient to add largely to the instruction force and so to reduce the sizes of the recitation divisions.

The preceptorial system, however, marks a spirit of reaction in American education against the advance of German methods and the spirit of fetichism towards the Ph.D. degree which exists to some extent. Without disparaging the value of such a degree when held by a live man of some sympathy, nevertheless the facts are that the degree has helped many men to secure teaching positions who have not the ability to teach, that hundreds of men who ought never to hold instructor's positions are seeking the degree for its propelling power to push them into college chairs, and that the effect upon men seeking the degree has been in many cases to make them largely interested in the acquisition of knowledge and very little in its dissemination. The Ph.D. degree undoubtedly signifies depth of learning, but knowledge may be very deep without having length or breadth, and such knowledge is of little use in a college instructor. A teacher, sensitive in his sympathies and keen in his interest in men, may be forgiven the lack of that final increment of knowledge which some deem so all-important. The lack of these neutralizes the advantages of great knowledge in a teacher. Here then is the advantage of the preceptorial system. It says distinctly to the preceptor that his first function is to keep in touch with the undergraduates as a guide and an adviser. If it is possible to possess a faculty with some sense of responsibility along these lines, or not possessing. one, if it is possible for an institution to add new men of the desired type sufficient to give this impress to its work, it would seem that a certain duplicating of effort necessary in the preceptorial system could be avoided. If neither of these is possible, then the building up of a new corps by the side of the faculty, but separate from it, is a remedy for present defects towards which all colleges and universities must soon turn.

While all Dartmouth men know of the high efficiency of the work of the Thayer School, not many know of its work in detail. The Thayer Society of Engineers, the alumni organization of the School, is so intimately connected with the work of the School, that a description of one naturally leads to the other. Graduates of the Thayer School of Civil Engineering have been employed at widely separated points. Only in recent years have many of them visited Hanover. In thirty years no call for a meeting was sent out. In smallness of number and wide separation. may be found, perhaps, the explanation of the fact that, for so long a time, former students met only by accident. In June, 1902, a meeting was held in New York, at which were present twenty graduates of the Thayer School or the College, as well as President Tucker, General Abbot and Mr. Snow, representing the board of overseers, and Professors Fletcher and Mann of the board of instruction. Since 1902 there have been five formal gatherings, the last on January 16 of the present year. The Thayer Society of Engineers is the outgrowth of the first three meetings. In December, 1903, it adopted a constitution and elected officers, At that time there were forty-one members. There is now a membership of about 150. The affairs of the society are entrusted to an executive committee of five, chosen annually. There is also an advisory board of seven. Members unable to attend the annual meeting vote by letter ballot. All meetings are held in the rooms of the Dartmouth Club, I2 West 44th Street, New York City. The object of the society "is to further the interests of the Thayer School of Civil Engineering : to promote social intercourse among its members, and to keep them informed as concerns the work and needs of said School." The Thayer Society publishes an annual containing about 100 pages ; this is the joint production of Professor Fletcher and the secretary, and includes such matter as was contained in the annual sent out by the School in several years preceding the organization of the society. The annual gives the courses of study, lists of officers and students, and a variety of interesting information, under a dozen or more heads. It also contains all available notes relating to former students in the Thayer School and the Chandler Scientific Department, and considerable other matter relating to the School and the society. The secretary's duties have been discharged with such skill as to insure a rapidly increasing usefulness on the part of the society. He has sent out, in some years, as many as a thousand letters designed to elicit information concerning former students at Dartmouth. The number and character of the replies have been gratifying. The membership of the society has increased steadily, many graduates whose homes are at a distance have been entertained in New York by members of the society, and the latter, with few exceptions, have become well acquainted with their fellows. The activity of the members has sufficed to make known to a large number the needs of the Thayer School and the invaluable work of the board of instruction. The number of graduates visiting the School in the course of a year has increased rapidly since the formation of the society, which now has the good fortune to be able to contribute considerable sums of money to the treasury of the School.

In looking over the "general list" (incomplete) in the back part of the last Thayer School Annual we find 113 or more names of alumni, from 1854 to 1894, who have been engaged in civil, mechanical, mining and electrical engineering and architecture. These are alumni of the Chandler Scientific School and College. They represent a vast aggregate of engineering activity for the most part with large and, in cases, with conspicuous success. Of these, 24 are members of the Thayer Society of Engineers. One of these is chief engineer of the Southern Pacific Railway, who has greatly improved the practice in railway curves; another has designed and constructed some of the largest mill-plants and water-power developments in the United States. The list also includes one of the most prominent electrical engineers of the country; one of its leading architects, who has had charge of remodelling the old and designing the new buildings of the College; a distinguished sanitary engineer; the proprietor of the oldest bridge and structural works in New England (Boston Bridge Works); a former chief engineer of the Croton Water Works, New York; the noted former superintendent of the Wash-burn Machine Shops, Worcester Polytechnic Institute (28 years); and others equally worthy of mention.

The Annual also gives information concerning 188 living graduates and former students of the Thayer School scattered in 34 states and territories of the United States and in six other countries. Of these more than 50 are located within the 50 mile limit of New York. Of this list 89 are members of the Thayer Society. (With the 24 before mentioned, the total membership is 113). All but about eight per cent of the total are engaged in engineering or closely related pursuits.

It is noteworthy that, although the Thayer School of Civil Engineering is a little one among larger institutions of the land, its graduates are doing a fair share of the "big work" of the present day. The Nestor among them, for the past 18 years the bridge engineer of the Boston and Maine railway system, has more than 3300 bridges of all kinds under his charge, and has designed the new bridges built under his administration, some of which are of notable size and importance. Dartmouth men can assure the public that the bridges of this system are carefully watched by an engineer noted as "safe" and conservative, and that no traveler on these lines need fear a bridge disaster.

One was chief assistant-engineer on the Kentucky and Indiana bridge, a great series of cantilevers spanning the Ohio, and is now engineer in charge of design and reconstruction of the Poughkeepsie bridge across the Hudson river, noted for its height and length. One has executed large contracts in New York City, his latest being 'nearly two miles of the subway system, chiefly in rock, and this without serious accident. One has built up a large and successful business in contracting for bridges and framed structure, having extensive shops on the main line of one of the trunk lines of New England. One was resident engineer on Thebes bridge, the latest completed great cantilever, spanning the Mississippi river. One has been employed in the design and erection of some of the notable steel-frame buildings of New York, including the Stock Exchange, and has lately designed the tallest building yet projected, thirty-five stories and 530 feet high, above the pavement. One has conducted some of the important recent surveys on the isthmus of Panama, and now has general charge of all the work on the Chagres liver above and including Gamboa. One served under the late George S. Morrison and assisted in the design of some of the largest railroad bridges in the West, including the Cairo and Memphis bridges, and is now in charge of design of railroad bridges in the principal office of the American Bridge Company in New York. One has been closely associated with Chief Engineer Newell of the United States Geological Survey in the investigations for and location of the great reclamation and irrigation projects in I3 states and two territories, to cost about 30 million dollars, aud is now supervising engineer in charge of investigations aud construction in five northwestern states. One directed the construction of the great Harvard stadium so effectively as to accomplish the apparently impossible task of completing it in one working season; and has since done extensive designing in reinforced concrete. One was chief engineer in charge of construction of one of the great paper-mill plants of the world, in Maine. One is chief engineer and superintendent of the pioneer company in the manufacture of compressed paving blocks, and has executed large contracts in leading cities of the East. One designed the steel frame-work for two of the largest power houses in the world, that for the Manhattan elevated railway and that for the Interborough subway system of New York, and is now doing similar work for the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. Of the more recent graduates one is field engineer on the erection of the Quebec bridge, the greatest cantilever and the longest span (1800 ft.) yet undertaken; two have had service in tunnel work by compressed air, one in the Hudson river tunnel and one in East river tunnel for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company; seven are in the United States Reclamation Service, engaged upon one or another of the great projects in the West; and one, of not quite two years standing, has been recently appointed district hydrographer in charge of all the gaging stations in North Dakota, Montana and part of Wyoming.

Six are doing important work as professors of civil engineering and heads of departments in educational institutions, and the majority of these are also engaged in engineering practice in the summer seasons. There is a good proportion of consulting engineers, chief engineers and managers of works, and others in responsible service in this profession, of which the great aim is "to direct the forces of nature for the use and convenience of man."

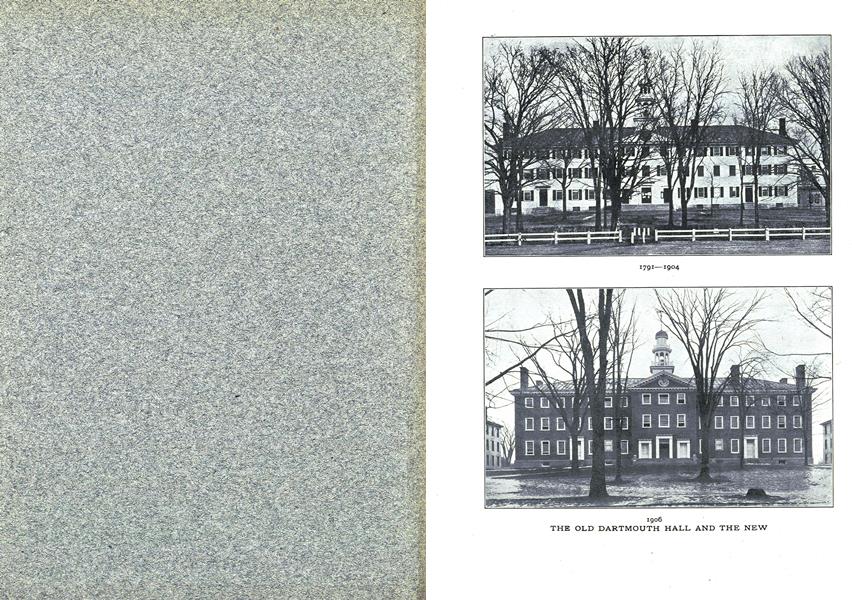

The new Dartmouth Hall has undertaken its mission. Nearly three hundred classes pass in and out of its doors each week. Calling to mind the old hall in its outward form and properly commemorating the spirit of the old College by its efficiency within, it stands a fit memorial to the Dartmouth Hall that the men of the College have known and loved. The responsibility of the heritage was assumed for the College of today and the College of the years to come by President Tucker in these words, at the dedication:

We therefore, who are here assembled, do here and now call to mind the heroism of the Founder of the College and of those who in immediate succession to him in the same heroic work laid the foundations of the ancient structure which stood upon this site.

We do here and now accept the inheritance of truth, augmented from generation to generation by those who wrought within its walls, committing ourselves with a like honesty of purpose and reverence of spirit to their unfinished tasks.

And above all, we do here and now with one accord implore the blessing of Almighty God who, through His gracious providence, hath in due time restored to us our "former habitation" giving us "beauty for ashes, the oil of joy for mourning, and the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness."

The College has welcomed two new men to its instruction force, at the beginning of the second semester:

Dr. George S. Graham, graduated from Dartmouth College in 1902, and from the Medical School in 1905, During his course he did special work in Pathology, and since graduating he has been pathological house officer at the Boston City Hospital. He comes to the Medical School as Instructor in Pathology.

Mr. Warren M. Persons takes up the work in Banking and Insurance in the Tuck School, and in Money and Banking, and Finance and Statistics in the College. He received the Bachelor's degree at the University of Wisconsin in 1899. Since that time, he has been instructor in Mathematics at Wisconsin, and at the same time has pursued graduate work in the Department of Economics. The subject of his thesis, "The Distribution of Wealth and Wages in the United States," is said to be the most exhaustive study of that field that has been attempted. Mr. Persons has assisted Professor Commons in the investigation of labor conditions and labor unions in Chicago, and has acted as special agent for the Wisconsin Tax Commission in its investigation of the relation between the assessed and market values of real property.

The reunions of the different alumni associations this winter have been unusually pleasant occasions. Short accounts of these are published in this issue under the Alumni Notes. The activity of the alumni all along the line is worthy of notice. Monday, February 5, President Tucker received this telegram :

"Pittsburgh, Penn.

"Greetings from Alumni Association of Western Pennsylvania, organized Saturday night.

"A. V. Barker."

Meanwhile the Boston Association had had its enthusiastic gathering of 230 men of the College, and Chicago had broken its own excellent record by the assembling of 123 Dartmouth men—really the record number for any association, if distance is taken into account. The reunions of the smaller associations are as significant, too, as these of the larger ones—a few men widely scattered, getting together without the attraction of numbers, influenced solely by College spirit.

The second annual Conference of the Secretaries, held at Hanover, February 16 and 17, furnished its own evidence of the alumni interest in the College. It brought together an even more representative - body than was present last year. Of the classes from 1867 through 1905, only six were not represented, and three of the six representatives had intended to come and were prevented at the last moment. Delegates were present from the classes of 1853, 1856, and 1857, and the new Dartmouth Club of Western Pennsylvania was represented by .its secretary.

It is not possible to picture the new Dartmouth Hall as it will finally appear, but it is interesting to compare the lines of the new and the old. Mr. W. H. Gardiner '76 presented those present at the Chicago Dinner with souvenirs of the occasion which showed such a comparison. The idea has been borrowed for the frontispiece herein.

The columns of the B1-MONTHLY are open for adequate discussion to any who take issue with views here expressed, whether in the editorial comment or in the general articles, Communications are invited,

1791—1904

1906 THE OLD DARTMOUTH HALL AND THE NEW

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

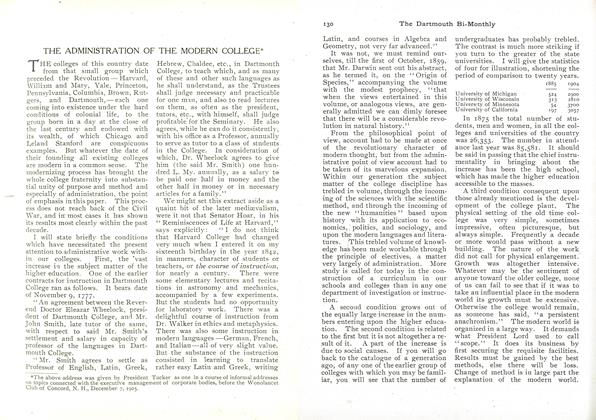

ArticleTHE ADMINISTRATION OF THE MODERN COLLEGE*

February 1906 -

Article

ArticlePRECEPTORIAL INSTRUCTION AT PRINCETON

February 1906 By Gordon Hall Gerould, '99 -

Article

ArticleTHE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS

February 1906 By Julius Arthur Brown '02 -

Article

ArticleTHE HEATING AND LIGHTING PLANT

February 1906 By Edgar H. Hunter '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesSECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES.

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleWASHINGTON'S BIRTHDAY EXERCISES

February 1906