Washington's birthday was observed February 22 with appropriate exercises in Dartmouth Hall. The program was particularly interesting to college men. Professors Fay, Vernon, and Richardson each showed the relation his Alma Mater bore to the Revolution; Professor Home compared the ideals of Dartmouth and Washington. Extracts from the addresses follow:

WASHINGTON AND DARTMOUTH

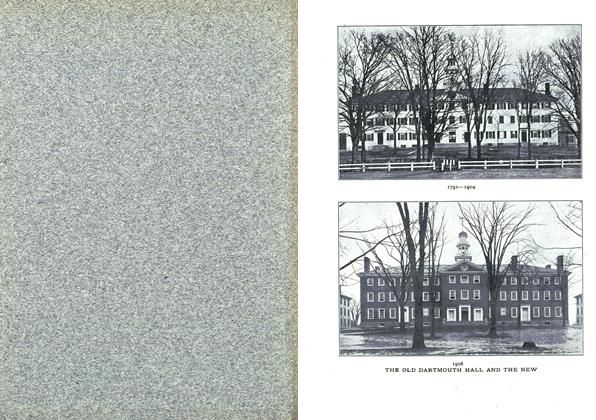

Professor Home said : On the occasion of the laying of the cornerstone of this new Dartmouth Hall, the Honorable Charles T. Gallagher traced the blood kinshipexisting between the families of Washington and Dartmouth. I desire today to indicate a certain kinship in ideals between the Father of this Republic and Dartmouth College.

Let the year be 1789. Washington is being inaugurated as the first president of the United States. Dartmouth Hall is in process of construction. John Wheelock, the son of Eleazar, and a lieutenant colonel in the Revolutionary Army, is President of the College. Washington is fashioning the ideals of the young Republic ; Wheelock is fashioning the ideals of the young college. Washington is the personification of service to his country; Wheelock is preparing for the service of the country such men as Daniel Webster, Sylvanus Thayer, George Ticknor, Thaddeus Stev ens, and Rufus Choate. It is my surmise, I cannot prove it, that John Wheelock, the soldier-pupil of Washington, set the stamp of public service on Dartmouth men.

Three great ideals will disclose the intellectual kinship of Washington and Dartmouth. These three are imbedded in the fond farewell address of Washington and the rich collegiate life of Dartmouth ; they are the ideals of democracy, of education, of religion. First an American, then a party man, says Washington ; first a college man, then a club man, says Dartmouth. "Promote ... institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge," says Washington ; " The same school may be enlarged and improved to promote learning among the English," says Dartmouth's charter, antedating the Revolution. "Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principles," says Washington; the powerful Hebrew words, El Shaddai, illumine the shield of Dartmouth.

THE RELATION OF HARVARD TOTHE REVOLUTION

Professor Fay said: Buildings when hallowed by time and long tradition win for, themselves a peculiar love and value. We all know how great this was in the case of Old Dartmouth. The old hall takes us back in its building to the days of Washington, so that it is especially appropriate that we are able to meet here in this New Dartmouth to celebrate his one hundred and seventy-fourth birthday, and to recall the part taken by American colleges in the Revolution. At Cambridge the building most closely associated with the Revolution is Harvard Hall. Its history and place in college tradition is strikingly similar to Dartmouth Hall. With its old bell, which summoned to daily prayers and recitations for nearly a century, it was the very center and heart of the life of the college. In was totally destroyed by fire, but within two years, by the efforts of the alumni, a new Harvard Hall rose over the ashes of the old. In 1769 the British put a military guard in King (now State) Street and pointed their cannon at the door of the State House, where the Provincial Legislature was sitting. When protests were without effect and the cannon could not be removed from the legislature, the legislature removed from the cannon. It adjourned, in fact, to the new Harvard Hall. When Washington was drilling order and discipline into the colonial recruits during the siege of Boston, Harvard Hall served as their barracks. After his masterful seizure of Dor-chester Heights, which compelled the British to evacuate Boston, Harvard recognized his preeminent greatness by conferring on him a degree which they had never before conferred on anyone—that of Doctor of Daws.

THE RELATION OF PRINCETON COLLEGE TO THE REVOLUTION

Professor Vernon said : I shall only dwell on three dramatic scenes of which Nassau Hall was herself the center.

First a scene in the prelude to the Revolution. In July, 1770, the merchants of New York retreated from their position to receive no further imports from England, and wrote by the post that passed through Princeton to the merchants of Philadelphia to request their concurrence. Hundreds of the students formed a solemn procession and to the tolling of the college bell marched to the center of the college yard, where they burned the selfish letter. This student assemblage assumes importance from the men who constituted it. In it were four members of the future Continental Congress, two of the Constitutional Convention, eleven of the Federal Congress, four governors, five judges, an attorney general, a vice president,and a president of the United States. The real patriotism of this assemblage was undoubtedly due to the president of the college, John Witherspoon, who, though but recently from Scotland, was one of the most prominent advocates of independence in the middle colonies. After the Declaration had been signed, the straw figure of Witherspoon was the largest in the group of effigies which the British sympathizers burned on Staten Island.

But the most sacred memory of Princeton, around which undergraduate life of today fittingly gathers, is the suffering she endured when Old Nassau was the storm center of the Revolution. It was natural that the British should desire vengeance on this hot-bed of rebellion and in mockery of Nassau should quarter the hated Hessians in the most imposing building in America. It was a dark hour for the colonies. Congress in terror had fled to Baltimore and had entrusted the country to the dwindling army of Washington. The other generals, doubting his capacity, and envious of his position, were guilty of flagrant insubordination; the inhabitants of New Jersey on every hand were accepting British amnesty; the treasury of the country was empty; the troops were kept from mutiny only by the near prospect of their home-going. It seemed impossible for Washington to live through the winter. Then it was that Old Nassau, in a campaign which, in spite of its small numbers, Frederick the Great denominated as the most masterly of the century, saw the battle fought under and within her walls, that, after the masterly stroke at Trenton, not only saved the remnant of the army and allowed it to retire to the hills of Morristown, but checked the British advance, saved Phila-delphia and made possible the decisive assistance of France. What wonder that the Princeton man rejoices at the cannon-ball of Hamilton's artillery that passed through the head of King George in the college library, and that today he breaks the last pipes of his college course against the old British cannon which was left to mark the successful issue of the triumphant retreat of troops, which, after Trenton and Princeton, refused to be returned to their homes.

And the final scene comes from the days of triumph in 1783, when, thanks to a handful of mutinous troops in Philadelphia, Old Nassau became the actual capitol of the nation. For several months the Congress of the Colonies met in the walls that were shot through in the battle of Prince-ton. Thither Washington came to receive the thanks of the congress for his services in establishing our independence. And.it is a proud day in Princeton annals when the Congress of the States adjourned, that with the French and Holland ministers and with the greatest man of all, George Washington, they might attend the Commencement of 1783 and hear the valedictory of Ashbel Green; who afterward became president of the college. Notwithstanding his own and his country's straitened circumstances Washington gave then a royal present to the college which had suffered with him in the cause of the republic, and through the wise application of the money by the trustees, the college now possesses an original portrait of George Washington in the very frame out of which the cannon shot the head of King George. It still hangs in the room where the congress held its sessions.

Surely Dartmouth men and Prince-ton men have reason to rejoice together that the institutional life of which they are a part strikes its roots into no modern merchant's riches and into no state's bounty, but into soil rich enough and ancient enough to have brought forth our nation.

DARTMOUTH AND THE REVOLUTION

Professor Richardson said that there was no immediate connection between Dartmouth Hall, built 1784-91, and the Revolution, but that the College, by reason of its frontier position and its relation to Indian education, was constantly and vitally concerned in the struggle. In the course of his account of the College during the war, he quoted President Wheelock's request to the Continental Congress for $500 "to supply my family—that is, the college, school, and those connected with it—" with firearms; and he read George Washington's reply to a congratulatory address by President Wheelock and the trustees in 1789, in which Washington called Dartmouth "an important source of science." In closing, Professor Richardson said: "In one respect Dartmouth College more closely connects the English people in its two homes than any other American institution. It never, like some other pre-Revolutionary colleges, changed the British name it had proudly borne.' Founded on soil over which George III ruled, and bearing the name of his Secretary of State for the Colonies, in the days of President Roosevelt it welcomed the present Earl of Dartmouth as a living proof of the fact that the republic of learning is broader than any national boundaries. May the friendship between England and America outlast even this stately hall, the cornerstone of which was laid by his loyal hand."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ADMINISTRATION OF THE MODERN COLLEGE*

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE practical workings of the preceptorial system

February 1906 -

Article

ArticlePRECEPTORIAL INSTRUCTION AT PRINCETON

February 1906 By Gordon Hall Gerould, '99 -

Article

ArticleTHE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS

February 1906 By Julius Arthur Brown '02 -

Article

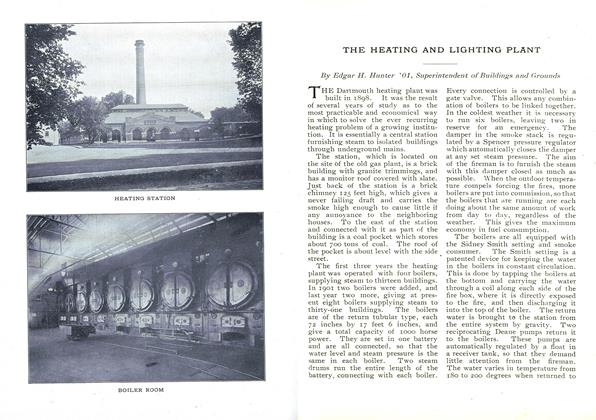

ArticleTHE HEATING AND LIGHTING PLANT

February 1906 By Edgar H. Hunter '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesSECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES.

February 1906

Article

-

Article

ArticleWORK ALREADY STARTED ON NEW DORMITORY

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Engagements

May 1933 -

Article

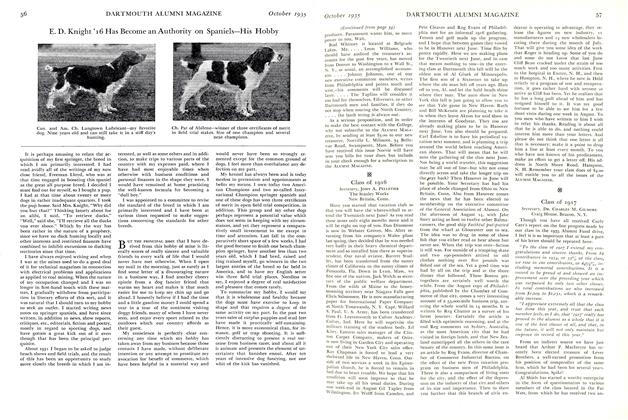

ArticleE. D. Knight '16 Has Become an Authority on Spaniels—His Hobby

October 1935 -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

March 1935 By Edward S. Wallace -

Article

ArticleThe New Great Issues

OCTOBER 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Jan/Feb 2011 By THE JOHN D. & CATHERINE T. MACARTHUR FOUNDATION