Through the very great kindness of Acting President Lord, and also of my old time friend Professor Palmer, of Harvard, I have been relieved of the more formal duties of the Commencement season. This relief enables me to sit at table with you today, and to take part briefly in the after dinner speaking, though, I regret to say, through the written word. Very naturally my thought runs today to the relation between the transient and the permanent in Our college life. This question of the transient and the permanent confronts us everywhere, but nowhere, I think, does it reach so happy a solution as here: for here we not only see, but feel, that the transient goes over into the permanent so naturally, almost imperceptibly, and with such a compensating jov that hardly a sign is left of the change. And this for the very simple reason that a college is not so much an institution as it is a movement, a procession. Nine tenths of all that pertains to a college is human, perhaps one tenth is material. I shall want to say something of the material embodiment of the College before I close, for it is very precious. But the perpetuity of a college lies in this ceaseless movement of life, in this ever-flowing stream which reaches the sea only to replenish the springs.

Here for example are two hundred men who are today passing out of the transient into their relatively permanent relation to the College. The undergraduate has his day. The coming years belong to the graduate. Go where he will, return as often as he will, present or absent, he is in and of the College, moving in its ampler freedom.

Here again are men to whom the permanent seems to be passing back into the transient. The decades have gone which have brought them to fifty, sixty, seventy, seventy-two years of graduate life. But here again the permanent is becoming the transient only to re-appear in the hope of a lasting permanency. Somehow our brethren as they become the men of the past seem to be nearer to the ever living personality of the College than we are. I chanced to read the other day a reference of Mr. Choate to the words in which Mr. Webster brought the College before the Supreme Court, '' I have brought my alma mater to this presence that if she must fall, she may fall in her robes and with dignity." Those words were spoken ninety years ago. Who amongst us today are as much alive in our relation to the College as were the actors in that scene!

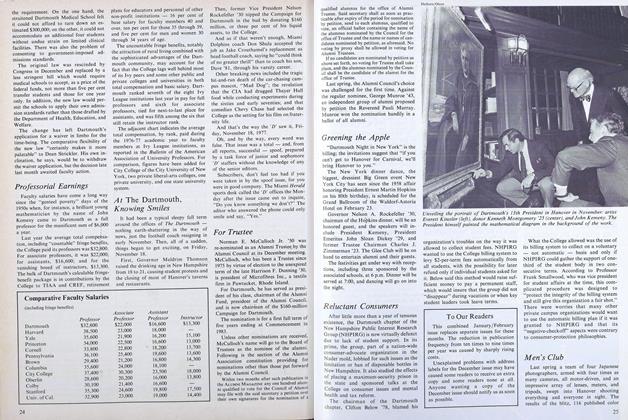

Here again we are come to a distinct change in the organized life of the College itself, a change of administration. Every administration stands for certain things which are relatively transient. When you have answered the questions which men so often ask, how much money, how many students, what new subjects, you have not necessarily said anything which relates itself very vitally to the future. These are only fragments of the great question which every administration has to apswer, not what it has done for the College in the way of annual return of any sort, but further and chiefly, in what condition does it leave the College to meet the always urgent demands of its immediate future. What a given administration does to insure the success of the next is the test by which it must be judged. When I took the College from Doctor Bartlett, there came over with the succession, not only the effect of his intellectural character and achievements, but also the results of a brave, self-denying, sacrificing administration. The decade of the 80's was a decade of financial struggle, sometimes expressing itself in sharp retrenchment, sometimes in persistent solicitation. It was in no small degree the resolute force of Doctor Bartlett, compacting the body corporate, at the price of much effort and no little hardship, which made possible the era of expansion which was to follow. The administration which now goes out must meet the like test. What has it made it possible for the incoming administration to accomplish? How firmly is the College established to meet the issues which await it? President Lowell has recently said that probably three fourths of American educators have ceased to believe in the college as an integral part of the educational system. That is not his unbelief, be declares emphatically. But in the re-assertion of his faith in Harvard College as well as in Harvard University, he announced distinctly one impending issue in our educational world. As my successor must make answer to present criticisms or unbeliefs concerning the college idea, is this College, now his college, in condition to enable him to speak with authority concerning its own future and with assurance to others of its kind? It is for my successor to say, within the fair limits of the policy which he may adopt, what the immediate future of the College shall be. The present administration will have little or no value to him in this outlook, unless it shall appear that it has left the College in condition for him to say what its future shall be. According to the value of this contribution the present administration passes away into the transient, or it passes out of the transient into the permanent. Some of the younger among you have been accustomed to speak of the New Dartmouth. Our President-elect, in addressing the undergraduates, the other day, spoke of the newer Dartmouth. That was right; the new is always passing over into the newer. So doing it lives. If it were not for this process, a college would not grow old, it would grow stale.

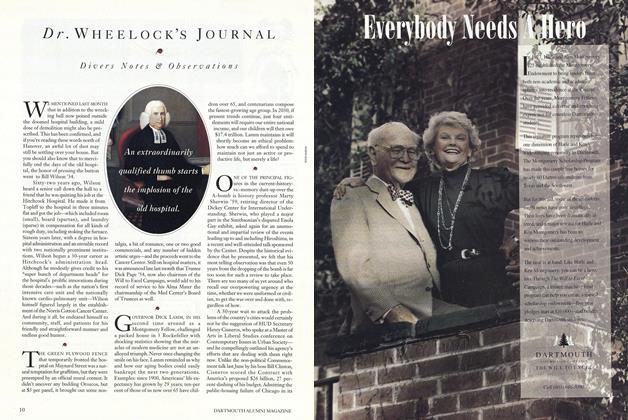

In the midst of the changes, however, which are involved as the transient gives way to the more permanent, it is quite easy to overestimate the element of change. Not infrequently the superficial aspects are emphasized. Not a little has been said in the daily press about the change of type represented in the election of a scientist to the presidency of Dartmouth College. I think that I have the mind of the trustees when I say that Doctor Nichols was elected to the presidency not because he was a scientist in distinction from an economist, a classicist, or a psychologist, but rather because being a scientist, he had reached such distinctfon as to reveal the quality of his mind, and also because he had reached a position broad enough and clear enough to give him outlook in other directions. While he was with us it was always a delight to follow him, so far as one might, in his scientific researches, but outside his laboratory I thought of him as showing the spirit of the humanist or the idealist quite as much as the spirit of the more technical scientist. In the search of these modern days for a college president, trustees can discover the man only through his worK, which to be significant must always represent some degree of specialization, but their search is no less for the man, and in the present case they are assured that they have found him.

I said as I began that nine tenths of all that pertains to a college is human, but that the remaining tenth, the material embodiment of the college, was precious. Always in the background of this steady movement of life stands the ancestral home. . The generation of college men come and go, and come back again and again. Thirty-five generations of men have come hither and gone hence, returning year by year in increasing throngs.

"Though round the girded earth they roam

The spell is on them still.

"The mother keeps them in her heart And guards the altar flame.

"Around the world they keep for her Their old chivalric faith."

This is college sentiment. We must be careful how and where we apply it. When we apply it to ourselves as sons of Dartmouth, we may not use it to hide one another's faults or to exaggerate one another's virtues. Once out in the world where man meets man, we are in the open competition for honesty, justice, and charity. But when our hearts turn hitherward, we need not be afraid of sentiment. Let the mother of us all know, by visible and enduring signs, that you love her. Let her never be made ashamed, in any respect, for herself, not simply for her sons, as she stands with the years falling upon her in the midst of the older and the younger colleges of the land. Better yet, see to it that her strength is as the strength of the hills which guard her, and her beauty like their beauty, simple, true, sufficient.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

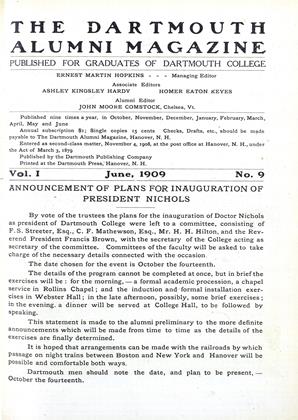

ArticleANNOUNCEMENT OF PLANS FOR INAUGURATION OF PRESIDENT NICHOLS

June 1909 -

Article

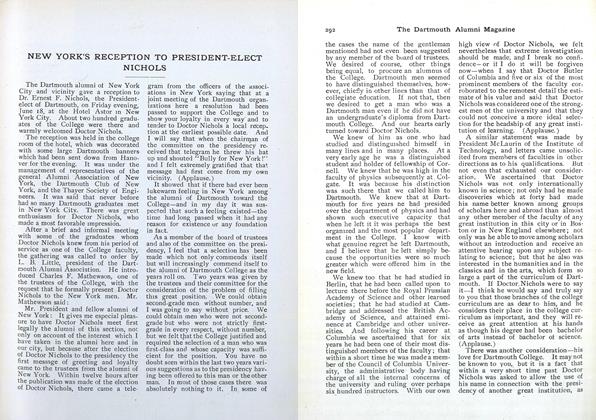

ArticleNEW YORK'S RECEPTION TO PRESIDENT-ELECT NICHOLS

June 1909 -

Article

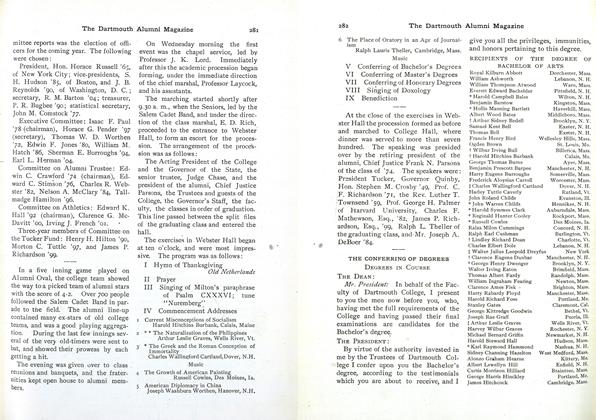

ArticleTHE CONFERRING OF DEGREES

June 1909 -

Class Notes

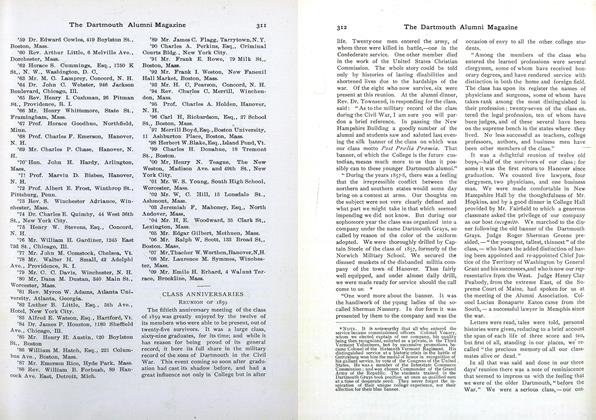

Class NotesREUNION OF 1859

June 1909 By Edward Cowles -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1909 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

June 1909 By Elmer W. Barstow