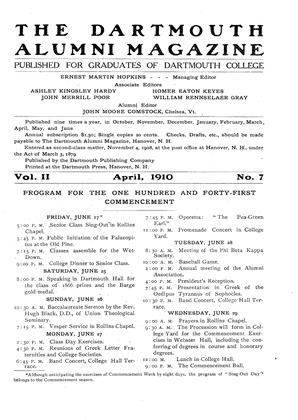

Amid all the argument of the present day concerning the function of the American college there is general agreement that its mission would be more completely fulfilled could the undergraduate be influenced to give his best effort to that for which he is first of all responsible,—his real college work. The statement frequently made, that no relation exists between college rank and accomplishment in after life, is as far from true as it could well be. In spite of the multiform activities of college life success in no one of them so much proves ability to achieve distinction in the world's affairs as does success in gaining high class-room rank Realization of this fact, if it could be brought home to college men, would unquestionably considerably affect undergraduate attitude toward curriculum requirements. From time to time, therefore, it is the intention to present in these' columns those facts which are too little known though accessible to him who : seeks for facts. The MAGAZINE is indebted to Professor J. K. Lord for the following illuminating statement, and to Mr. E. H. Hunter for designing and drawing the graph.

The current discussion of the condition of scholarship in the colleges naturally suggests a consideration of the relation of college standing to the work of after life. Is there any relation between them? Many teachers, as well as students,, are dissatisfied with the small amount of work done by students in college, and yet when some students by their devotion to their studies reach a high rank their fellow students and often their teachers look upon them askance as representing a class whose value to themselves and the college is not entirely clear. A man who can attain high rank may therefore ask what is that golden mean of work that keeps one from being regarded as inefficient on the one hand, and, on the other, from being exposed to the opprobrious epithet of "grind," and from being considered as one who in attaining high scholastic rank is a type that no healthy American youth would care to represent. All agree that scholarship in college is desirable, and also that it is not the same as college rank or necessarily expressed by it. Few, perhaps, define to themselves exactly what they mean by it, but they hesitate to associate it with high standing. Yet it seems possible that there may be some connection between it and high standing, not because such standing insures it, but because it is rarely obtained without such standing. And, furthermore, while neither scholarship nor high standing insures later success, both are supposably aids to it. Scholarship, however defined, would certainly be a help in life. Does high standing imply any qualities that justify the expectation of later success, beyond that which follows lower standing ? Do those who attain high standing have any greater measure of success than others? Experience may help to answer the question.

It is impossible to make an exact estimate of success, for it is different for different men, but in order to make a comparison between the success attained by men of different college standing it is necessary to take something that will serve as a kind of standard. That may be roughly afforded by "Who's Who? ' It is, of course, not an exact standard; many are not mentioned in that book who are as deserving of mention as those whose names are given, but it may be taken for granted that as between different grades of given classes it is impartial, that the principle of selection is the same for different grades of scholarship, and that it omits no more names that it ought to contain from one grade than from another.

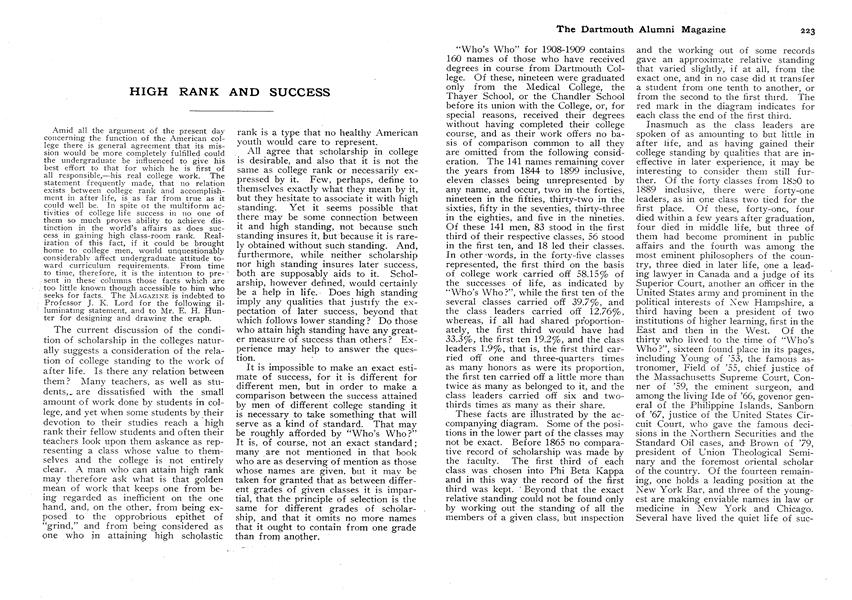

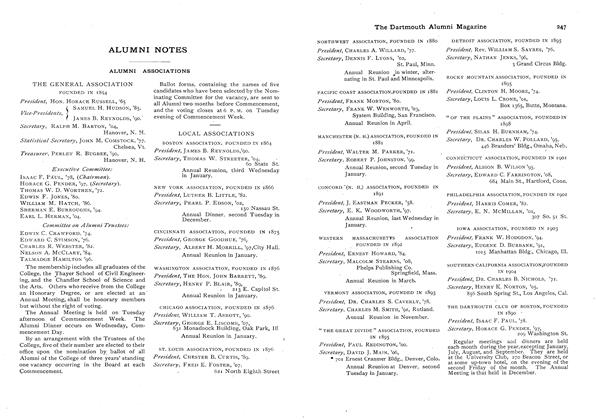

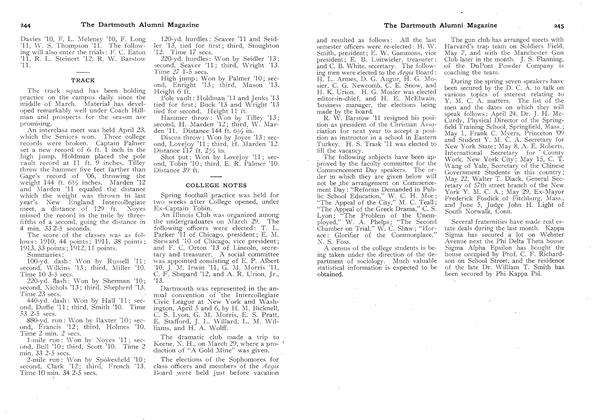

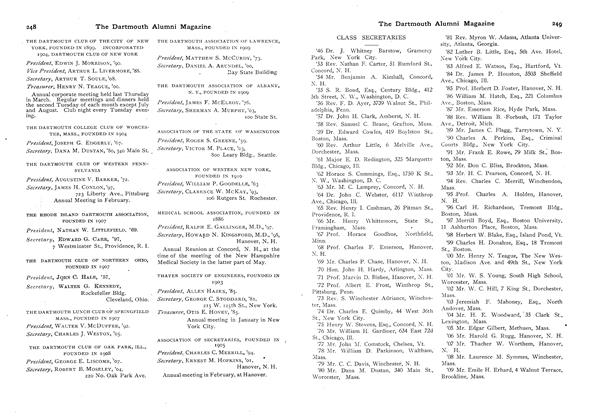

"Who's Who" fox* 1908-1909 contains 160 names of those who have received degrees in course from Dartmouth College. Of these, nineteen were graduated only from the Medical College, the Thayer School, or the Chandler School before its union with the College, or, for special reasons, received their degrees without having completed their college course, and as their work offers no basis of comparison common to all they are omitted from the following consideration. The 141 names remaining cover the years from 1844 to 1899 inclusive, eleven classes being unrepresented by any name, and occur, two in the forties, nineteen in the fifties, thirty-two in the sixties, fifty in the seventies, thirty-three in the eighties, and five in the nineties. Of these 141 men, 83 stood in the first third of their respective classes, 56 stood in the first ten, and 18 led their classes. In other -words, in the forty-five classes represented, the first third on the basis of college work carried off 58.15% of the successes of life, as indicated by "Who's Who?", while the first ten of the several classes carried off 39.7%, and the class leaders carried off 12.76%, whereas, if all had shared proportionately, the first third would have had 33.3%, the first ten 19.2%, and the class leaders 1.9%, that is, the first third carried off one and three-quarters times as many honors as were its proportion, the first ten carried off a little more than twice as many as belonged to it, and the class leaders carried off six and twothirds times as many as their share.

These facts are illustrated by the accompanying diagram. Some of the positions in the lower part of the classes may not be exact. Before 1865 no comparative record of scholarship was made by the faculty. The first third of each class was chosen into Phi Beta Kappa and in this way the record of the first third was kept. ' Beyond that the exact relative standing could not be found only by working out the standing of all the members of a given class, but inspection and the working out of some records gave an approximate relative standing that varied slightly, if at all, from the exact one, and in no case did it transfer a student from one tenth to another, or from the second to the first third. The red mark in the diagram indicates for each class the end of the first third.

Inasmuch as the class leaders are spoken of as amounting to but little in after life, and as having gained their college standing by qualities that are ineffective in later experience, it may be interesting to consider them still further. Of the forty classes from 1850 to 1889 inclusive, there were forty-one leaders, as in one class two tied for the first place. Of these, forty-one, four died within a few years after graduation, four died in middle life, but three of them had become prominent in public affairs and the fourth was among the most eminent philosophers of the country, three died in later life, one a leading lawyer in Canada and a judge of its Superior Court, another an officer in the United States army and prominent in the political interests of New Hampshire, a third having been a president of two institutions of higher learning, first in the East and then in the West. Of the thirty who lived to the time of "Who's Who ?", sixteen found place in its pages, including Young of '53, the famous astronomer, Field of '55, chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, Conner of '59, the eminent surgeon, and among the living Ide of '66, govenor general of the Philippine Islands, Sanborn of '67, justice of the United States Circuit Court, who gave the famous decisions in the Northern Securities and the Standard Oil cases, and Brown of '79, president of Union Theological Seminary and the foremost oriental scholar of the country. Of the fourteen remaining, one holds a leading position at the New York Bar, and three of the youngest are making enviable names in law or medicine in New York and Chicago. Several have lived the quiet life of successful teachers, and but a small part has failed to show in later life the qualities of leadership indicated in college.

But if it should be said that these classes represented mainly the old order of general competition under a system of prescribed studies, when there was a more constant rivalry between individuals in common subjects, and that under the elective system the same results may not be secured, it is interesting to observe the record of the class leaders in the nineties, after the elective system was well established. Of the class leaders from 1890 to 1899 inclusive, three are promising lawyers in Boston, one having been a member already of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate, three are professors in college, two in Dartmouth and one in the West, one is an astronomer of rising fame among astronomers, one is a state superintendent of Education in New England, and two represent business and the ministry.

These facts seem to clearly show that while high standing in college gives no assurance of later success, it is an indication of qualities that are likely to bring success, and that if it does not prove the possession of superior abilities, yet it implies a steadfast purpose and a controlling will that may make medium abilities more effective than greater abilities not under such direction. Standing in the first third of a class or being a class leader does not constitute a charm to entice success, but such a position is a promise for the future, and it is as true now, as it has been in the past, that the first third of a class carries off more of the subsequent honors of life than the other two-thirds together, and that in that third the scale of gain increases toward the top.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Article

-

Article

ArticleD. C. A. ENTERTAINS BOYS AT ITS WINTER CAMP

March, 1923 -

Article

ArticleServices for Mrs. Tuck

JANUARY 1929 -

Article

ArticleLanguage Study Grant

DECEMBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleA Guy Named Joe

May 1981 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1970

Nov/Dec 2004 By Eric Smillie '02 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

December 1947 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29.