Before another issue of the Magazine the Commencement of 1910, the one hundred and forty-first at Dartmouth, will have become to many a vital memory of friendship renewed and of college connections revivified. For months reunion committees have been at work, recalling to the minds of classmates the plans and opportunities of celebrations to-be. Perhaps it will afford material for some fuhaps commentator on the complexities of present day college life that even the spontaneity of class- reunions is much more marked under careful organization and painstaking arrangement. Suffice to say, however, that the class gatherings of the present day bring to the College impressions of the graduates which are a delight to recall, and in turn the alumnus sees his college in dignified ceremonial befitting the occasion for which Commencement stands. To the Senior the time cannot but have a portion of sorrow, but to the graduate it brings gladness of a sort not to be duplicated in any other way. So the invitation is written large to all whom Dartmouth has mothered, “Come back to the New Hampshire hills.”

‘‘The sons of old Dartmouth, The laurelled sons of Dartmouth— The Mother keeps them in her heart And guards their altar-flame.”

The long-time need for an administra- tion building of convenience and dignity commensurate with the other Dartmouth buildings has been met by the generous gift of Mr. Parkhurst ’7B, and Mrs. Parkhurst, in memory of their son, Wil- der L. Parkhurst ’O7, who died at the beginning of his sophomore year. This gift in its utility will give great satis- faction not only to the Trustees and officers of the College, but to the large number of Dartmouth men among the alumni who have felt that the time was at hand when such a building ought to be erected for the appearance of the Col- lege plant as a whole. But as a memo- rial it is a gift of particularly fine sen- timent.

Wilder L. Parkhurst's death took from Dartmouth one whose impress upon the College was remarkable for the brief time in which he was a student. From his earliest youth possessed of strong desire to become a member of his father's college, after entrance he was quick to understand and cherish the bet- ter things of college life, and was clear in his ideals and effective in stiiving after them. His friendship held men who knew him best with peculiar inti- macy, and his keenness of intellect and masterfulness in things of the mind commanded admiration from all. He led his class in scholarship with a mark to which there was no close second ; he gave to his intimates a friendship even as hearty as that which they gave him; and he revered his college with a love which made him ever solicitous for her best in- terests and ambitious to do for her as well as for himself his man's work. Those who knew him will welcome the perpet- uation of his name in such a memorial at the College, and those who knew him not should know his name,—the name of a true son whose life would have meant more than anyone can know could it have been spared to the College he loved so well.

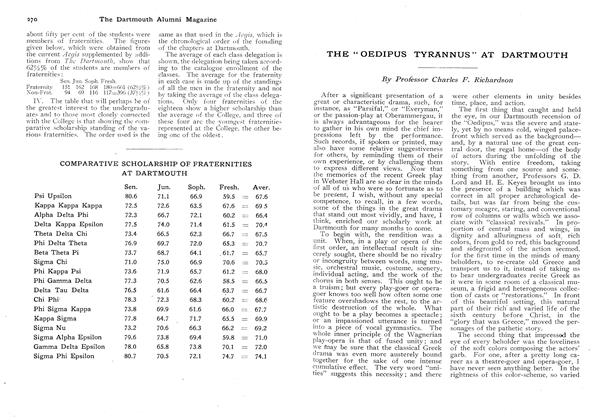

It is well that alumni year by year should have acquaintanceship with the names of members of Palaeopitus. for these are the men whom the undergradu- ates have placed in position properly to represent them. There is reason for sat- isfaction in the outcome of this year’s elections, for it is a clear indication that the excellent work of the organization has won for it the respect of the student body at large. The junior class, en- trusted with the selection of six of the eleven members, accepted its task in a spirit of' impartial seriousness in which fraternity politics or private ambition had no place. The active delegation, which chose the remaining five, exhib- ited the same fine desire to serve the best interests of the College. As a result the Palaeopitus of the class of 1911 will be even in unusual degree representative and in equal measure able to cope suc- cessfully with the problems that may come before it. The men are of a type that should see in this election not so much a great honor as a great respon- sibility demanding the best that in them is of loyalty and devotion. They are : Harry M. Bicknell, Malone, N. Y. James J. Conroy, Gardner, Ma«s. Arthur S. Dunning, Duluth, Minn. Oro E. Holdman, Seattle, Wash. Jonathan E. Ingersoll, Cleveland, Ohio. James M. Irwin, Quincy. 111. Robert B. Keeler, Cleveland. O, Austin C. Keough, Brooklyn, X. Y. George M. Morris, Chicago, 111. John A. Mullen, Jr., South Boston, Mass. Raymond E. Palmer, Paducah, Ky.

Prom Week, while of no immediate interest to a large proportion of Dart- mouth alumni, is an event in the College calendar with which a constantly increas- ing number of friends has had personal and pleasant acquaintance. Though but eleven years old,—a comparatively re- cent feature of our student life,—to the undergraduate, no doubt, it seems in- vested with the sacredness of primeval tradition, to depart from which would spell disaster. It is tradition that puts the Prom in May. The first one was held during the second week of that ca- pricious month; the latest—owing to suc- cessive years of sad experience with the chill vagaries of reluctant spring—was held during the last week. Examinations and Commencement will tread close upon its heels: baseball, track athletics and the Greek play trod upon its toes. If early May is too cold for Prom, it has become fairly apparent that late May is too crowded. It would seem high time to re- construct tradition. Truth to tell, the only reason why the Prom was and is held in May is that it was first thought of in April. Some credit perhaps is due to those who had the thought; but more will be due to those who have courage to revise it. The spring is lovely every- where, and mere living then is a joy that needs no orchestral accompaniment. But the Hanover winter is a thing apart. What college other than Dartmouth can offer such hospitality of open hearth, such crisp vitality of atmosphere, such zest of snow sports elsewhere unknown or at best but seldom enjoyed? The fact is that we have so much winter that in- stead of making the most of it, we allow it to get on our nerves. Illumine it with a little timely gaiety, and we should see it as it is, one of the finest assets of our New England life.

Memory does not avail to recall to us when the spirit of commercialism as ap- plied to the solution of educational prob- lems has had more striking expression than is afforded by the Report on Amer- ican Medical Education just issued by the Carnegie Foundation. In view of the fact that the Board is working with a bona fide desire to correct real abuses its findings deserve respectful considera- tion. But even after that is given, we have a few reflections to which we can- not forbear to give expression. In par- ticular, exception is taken to the basis on which the judgment was made. In pur- suance of its policy of acting as the cen- tral directing force in the educational field, this body has conducted an inves- tigation into the present status of med- ical teaching in this country, and as a result of this investigation publishes a critique bringing grave charges of in- efficiency against a large majority of the American and Canadian schools. The report is interesting, as showing the as- sets of the various schools as far as these may be judged on the money basis. Fur- ther than this there is reasonable question as to how far the ascertained facts ren- der justifiable the conclusions that have been drawn.

The fallacy inherent in the proposition that the efficiency, whether of a man or of an institution, may be computed ac- cording to a scale whose units are dollars of wealth possessed, is too apparent for comment. Yet when any mathematical computation becomes necessary, this item of visible assets must have a commanding position, since it is most readily deter- mined. When educational institutions are to be standardized the most available basis for such standardization is afforded by such mathematical facts as numbers of. students and faculty, annual expendi- tures, and permanent valuation of build- ings and equipment. Let us have such valuation, so that all may know how much of invested wealth stands behind the graduate of a given institution, but let us not forget, before passing judg- ment upon the efficiency of our graduate, that he is a sentient being, and as such, not to be dealt with according to the prin- ciples governing the preparation of a tar- iff schedule.

Back of all else in the conduct of any educational institution is the spirit of teaching which creates for it the atmos- phere which is its individuality. This individuality it imparts to its students. The reform school and the orphan asy- lum also stamp their seals upon former inmates. These seals are unvarying be- cause the methods prevailing in such in- stitutions are uniform. But in the col- leges, the individuality which.is the re- sult of freedom gives to the graduate a source of personal power which remains with him as a perpetual inspiration. That constant supervision of medical ed- ucation is necessary, no one interested in it would wish to deny, but the necessary regulation must be determined from the humanitarian not from the commercial standpoint. The vital question is not

“How much money has been expended in educating this man,” but, “How thor- oughly has he been educated?” The mediaeval standardizer of men asked “Were this man’s parents of the landed nobility?” Today we ask “What can the man do ?”

In this matter of personal efficiency of the individual graduate lies the ra- tional basis upon which the school should be judged, if judged it must be. Infor- mation as to this cannot be gained by study of financial reports. The math- ematically inclined investigator gets no glimpse of it. Within the medical pro- fession itself, where machinery counts for little, while finished product is sub- jected to close scrutiny, the efficiency of the various schools is more accurately judged. Hence arises the anomalous condition that the Dartmouth Medical School is adjudged by the Carnegie Foundation inefficient while its graduates are recognized by their fellow-laborers as men thorough!}- well trained, able and willing to take their places beside men of the larger schools and to compete suc- cessfully with them, whether in the writ- ing of examinations, or, what is of far greater moment, in the competent con- duct of hospital or of private practice.

The graduate of the small medical School whose standards are justly main- tained is a product of the conscientious personal instruction of his teachers. He goes out into his life work with a thor- oughly classified theoretical training upon which he has built a clinical ex- perience varied enough to give him an understanding of any of the conditions he may be called upon to meet. His clinical knowledge has come from the contemplation of “cases,” and clear log- ical thinking has become the basis upon which his judgments are drawn. Fie has not been blinded by that very wealth of “clinical material” whose value looms so large in the eyes of the statistician; he has become neither an automaton nor an egotist. He carries with him an enthu- siasm not yet satiated, and withal, there is in him that spirit of humility and of dependence upon his own God-given fac- ulties which serves to keep his mind and heart fresh. These are facts not availa- ble for tabulation. That they are real is proven by new experiences many times repeated.

That day will be a most unfortunate one for true medical education when all medical schools shall be compelled to sur- render their individuality in order that they may conform to the dicta imposed upon them by a board of laymen. Reg- ulation is necessary and will always be welcomed. Repression and the unfore- seen establishment of artificial standards should not be tolerated.

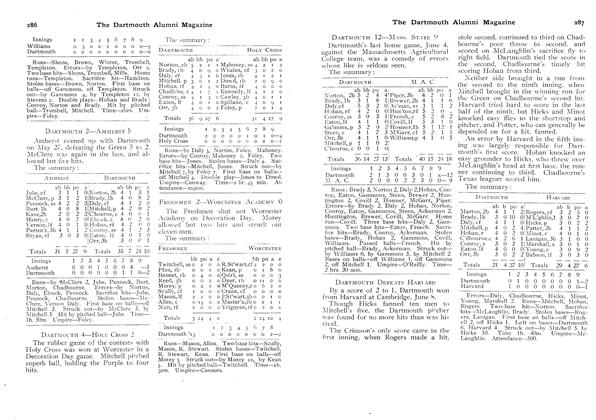

The baseball season has come to its close, and the opinion is widespread that no baseball team at Dartmouth in a decade has accomplished so much in pro- portion to its natural ability as the team of 1910. Coach Ready taught with re- markable success a team of very medio- cre native ability to play a skillful and interesting game, and Captain Norton has proved an inspiring leader. To these two men, especially, congratulations should be extended that are likewise ex- tended to all members of the team. And to the College at large, most of all, con- gratulations are to be extended, for the interest which has so conspicuously lagged in recent years has to a consider- able extent been revived, and under like conditions will return more and more. More than any game baseball is adapted to informal play among the undergrad- uates. Almost everybody plays it to Some extent, and a large number of men play it fairly well. During the days of spring practically every available plot of ground on or about the campus is occu- pied by impromptu games. Unquestion- ably this admirable spirit of outdoor play gets a powerful impetus in the reflex from intelligent and inspiring play in the intercollegiate contests. At a time, then, when there is so much encouragement in our own baseball situation, perhaps we can comment more impartially upon the general proposition of baseball as a col- lege sport.

With football hardly out of the throes of enforced metamorphosis, murmurs of protest against certain phases of col- lege baseball are becoming more than audible. In the April Scribner's, Presi- dent Pritchett reviews the evolution of this as a college game. As a former participant in the game and an ardent admirer of its good qualities as an inter- collegiate sport, he speaks intimately and with authority.

Among other things. Doctor Pritchett notes the tendency of the college game to imitate the professional game not only in matters of technique and spirit of play, but extending'to the conduct and spirit of partisan spectators. In this tendency

he finds the reason for some of the re- grettable features of intercollegiate base- ball contests. Commenting upon the “in- discriminate yelping'' of the typical game, he writes;

"Such games as. for example, the last Harvard-Princeton matches are enough to disgust the ordinary man with the whole game of baseball. Not only is the * audience subjected to a continual chorus of cries from the players, but the audi- ence itself is encouraged to take a hand in the game by concerted cheering and calls. The result is that the visiting nine has to play against the home- nine, but it has to play also against the home audi- ence. This whole process is absolutely unfair. It is vulgar in the last extreme and college men ought to stop it.”

In accord with the foregoing and possibly taking a cue from it—the recent report of Dean P>riggs, Chairman of the Harvard Athletic Committee, protests against the unfair practices commonly at- tendant upon college baseball games.

An equally significant protest issues frequently from the editorials of various college journals in which the adherents of home teams are taken to task for ex- hibitions of unsportsmanlike and inhos- pitable attitude toward visiting teams. •

But criticism does not stop with ques- tions of the etiquette of the intercollegi- ate diamond ; it takes the form of an at- tack on various features which in recent years have come to be looked upon as necessary and natural adjuncts of the game. Without further citation of in- dividual critics, their charges may be re- solved into an attack upon certain ele- ments of professional baseball which have been engrafted upon the college game.

A' common point of attack is the prev- alent custom by which the college coach, through a system of signals, directs the details of play. There can be no ques- tion as to the facts upon which the criti- cism is based: the practice is almost uni- versal and is becoming more and more conspicuously an accepted feature. Moreover, the point of the criticism seems to be well taken. Just why the custom should be tolerated in baseball, while in football sideline coaching is ac- counted bad form and cause for severe penalty, is not apparent. Such partici- pation by coaches injects into the game an element entirely out of place in an intercollegiate contest.

But the most serious charge brought against the results of the coaching of the usual professional is that it includes so many features which are not baseball at all, but which are simply attempts to se- cure unfair advantage through infrac- tions of rules and by successful avoid- ance of detection and penalty. Everyone knows that this charge is based upon fact; what is more, everyone knows that such tactics have come to be accepted as part of the game and that their successful perpetration is commonly hailed as one criterion of superior baseball sense and skill. The average college man, never- theless, participating in other games of skill or chance, holds cheating in con- tempt and regards the cheater as a fit subject for Social ostracism. That he should not only condone cheating and rough play in an intercollegiate game, but actually applaud it, in itself consti- tutes a serious charge against present- day college baseball. If the charge is • well founded—and it seems hardly ca- pable of denial—.then we must grant the truth of Dean Briggs’ contention that baseball is the college sport most need- ful of reform, that the element most worthy of attention is not the physical danger, but a moral one.

There are, other growths in the col- leeg game sorely in need of the prun- ing knife. But the foregoing points have been touched upon because they are most the points of attack, and moreover, the most vulnerable to attack Considering the popularity of baseball as the great national game, it is hardly to be wondered that the college game, quick to grasp and to adapt the elements of in- creased skill in play as developed in pro- fessional baseball, has unfortunately also taken over some of those characteristics so dear to the metropolitan bleachers. So it is that many of the characteristics of modern college baseball may pass as good baseball. But they can scarcely pass as good sport—and when college baseball passes from the realms of good sport, it is incumbent upon the game’s supporters to yank it back.

The strong stand against professional- ism, taken by so many colleges, in their eligibility rules, marks a distinct forward step. But the line of demarcation be- tween professionalism and amateurism is, at best, arbitrarily drawn, and has, there- fore, only too little potential influence upon the spirit of the game. If the pro- fessional spirit continues to pervade aud increasingly becomes dominant over the college game, then surely the attempt through eligibility rules to eliminate pro- fessionalism loses much of its force, aud becomes an element largely of superficial significance.

To the lover of baseball the indict- ment of the college game might present a discouraging problem, were it not for the fact that the problem is so clear aud its solution so easy. The control of the situation lies absolutely in the hands of the coaches; students are susceptible to the influence of the coach, receptive to his instruction, and amenable to his dis- cipline to a degree that, if even ap- proached in other branches of college in- struction,- would solve the major prob- lems of education. The power of the coach sways not only the team, but by lifting his hand, he is able to con- trol the exuberance of the team’s sup- porters. Once a considerable number of the coaches of our college teams come to the realization that what is wanted among the colleges is baseball the sport, and not baseball the business, then the game will take care of itself.

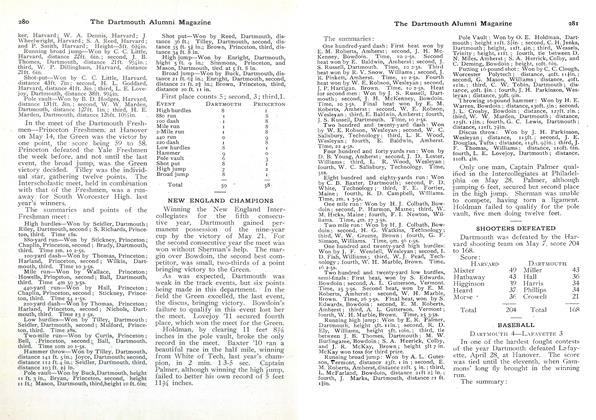

The appreciation of the work in track athletics of Mr. Hillman is well merited. Called to his work in the middle of the year, he had a peculiar problem. He did not know the men; large point win- ners of last year’s team had been lost through graduation, and the freshman rule in its first year of operation gave no access to new material: and finally a most unusual series of accidents cut out one and another of the men upon whom he would naturally have relied to give the College its proper representation How- ever, the enthusiasm of the teacher was contagious, the resources at hand in the upper classes were utilized to the max- imum, and deprived little by little of strength upon the track, the field events were carefully provided for by ever pa- tient training, until in spite of all adver- sity the New England Intercollegiate meet was won and the track strength of previous years was held through what might have been a year of discouraging retrogression. The situation is now read)' for a great constructive work, and no question exists in the College that Mr. Hillman is the man to undertake this and carry it on to achievement hitherto un- equalled in Dartmouth’s track history.

The recent thoroughgoing installation of fire-escapes in the dormitories—not only ladders upon the exteriors of the building but ropes in all the rooms above the first floors—gives additional assur- ance of safety to those who room therein. A careful examination likewise has been given to the recitation buildings and they likewise have been safeguarded. With the long-time policy of frequent and care- ful sanitary inspection of all buildings, the recent methods of absolutely fireproof construction, and now the provision of every conceivable means for adequate precaution, it would seem that the phys- ical risks of a college education could not much more be diminished, for hardly can they be calculated.

It is probably needless to say to read- ers of these columns that the grammatical vagaries of Mr. Lord’s statement about scholarship, in the last number, were due to errors in proof-reading, and not to any error in original copy. Though Pro- fessor Lord has asked for no correction, the fact should be recorded that it is most unintentional when the contribu- tions of friends are so treated herein.

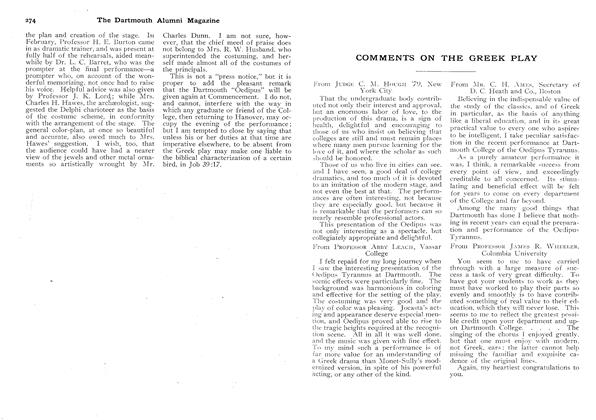

The question of what things are to be done by a college is really of less im- portance than the way in which things are done which are undertaken. There is all the time an increasing, insistence evident at Dartmouth that those1 things undertaken shall be so well done as to be noteworthy. What more, then, can be said in regard to the Greek play presentation than that it satisfied every possible demand of the most solicitous Dartmouth man. It was a performance that commanded praise in every partic- ular. To all concerned, and particularly to Mr. Flint, Mr. Bartlett, and Mr. Adams of the undergraduates, and to Professor Adams and Professor Hus- band of the faculty, heartiest congrat- ulation is due.

This number of the Magazine has been purposely delayed in order to in- clude college news up to the time of the beginning of the examination period. Thus the columns of the next issue will be comparatively clear for news of the Commencement.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTUCK SCHOOL ORGANIZES NEW CLEARING HOUSE

November 1923 -

Article

Article"The Iron Major"

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

June 1954 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1971 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

DEC. 1977 By S.G.