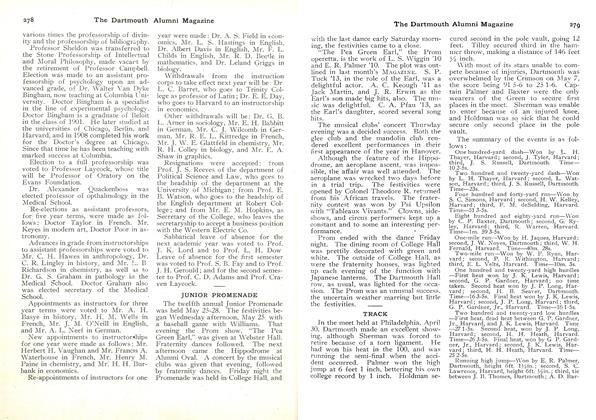

After a significant presentation of a great or characteristic drama, such, for instance, as “Parsifal,” or “Everyman,” or the passion-play at Oberammergau, it is always advantageous for the hearer to gather in his own mind the chief impressions left by the performance. Such records, if spoken or printed, may also have some relative suggestiveness for others, by reminding them of theirown experience, or by challenging them to express different views. Now that the memories of the recent Greek play m Webster Hall are so clear in the minds of all of us who were so fortunate as to be present, I wish, without any special competence, to recall, in a few words, some of the things in the great drama that stand out most vividly, and have, I think, enriched our scholarly work at Dartmouth for many months to come.

To begin with, the rendition was a unit. When, in a play or opera of the first order, an intellectual result is sincerely sought, there should be no rivalry or incongruity between words, sung music, _ orchestral music, costume, scenery, individual acting, and the work of the chorus in both senses. This ought to be a truism; but every play-goer or operagoer knows too well how often someone feature overshadows the rest, to the artistic destruction of the whole. What ought to be a play becomes a spectacle; or an impassioned utterance is turned into a piece of vocal gymnastics. The whole inner principle of the Wagnerian play-opera is that of fused unity: and we may be sure that the classical Greek drama was even more austerely bound together for the sake of one intense cumulative effect. The very word “unities” suggests this necessity; and there were other elements in unity besides time, place, and action.

The first thing that caught and held the eye, in our Dartmouth recension of the "Oedipus," was the severe and stately, yet by no means cold, winged palacefront which served as the background— and, by a natural use of the great cen- tral door, the regal home—of the body of actors during the unfolding ol the story. With entire freedom, taking something from one source and some- thing from another, Professors G. D. Lord and H. E. Keyes brought us into the presence of a building which was correct in all proper archaeological de- tails, but was far from being the cus- tomary meagre, staring, and conventional row of columns or walls which we asso- ciate with “classical revivals.” In pro- portion of central mass and wings, in dignity and alluringness of soft, rich colors, from gold to red, this background and sideground of the action seemed, for the first time in the minds of many beholders, to re-create old Greece and transport us to it, instead of taking us to hear undergraduates recite Greek as it were in some room of a classical mu- seum, a frigid and heterogeneous collec- tion of casts or “restorations.” In front of this beautiful setting, this natural part of their rich' and varied life of the sixth century before Christ, in the “glory that was Greece,” moved the per- sonages of the pathetic story.

The second thing that impressed the eye of every beholder was the loveliness of the soft colors composing the actors’ garb. For one, after a pretty long ca- reer as a theatre-goer and opera-goer, I have never seen anything better. In the rightness of this color-scheme, so varied yet never incongruous in its parts, the mind went back now to “Parsifal,” now to Goldmark’s “Queen of Sheba,” as staged at the Metropolitan some years ago. I hope that I shall not fall into an anti-climax when I add that it seemed as though some of the treasures of Lib- erty's, in Regent Street, had been fitly be- stowed upon the adornment of Hellenic antiquity. There is no longer any ex- cus for thinking of the classical Greek man or woman as a partially animated plaster cast, illuminated by calcium light.

Next in noticeableness were the in- comings, the outgoings, and the attitudes of the actors and mutes. Their all-prev- alent slowness of motion lent itself well to dignity, but there was little of that stiffness which so often characterizes the undergraduate when he feels the serious burden of occasion. The men had lived in the play so long, had been so well drilled, that they had caught and kept the spirit of Greek tragedy. To tell the hpnest truth, the elaborateness of the Hellenic sidewalk committee, with its occasionally heavy silence and its plati- tudes of obvious “I-told-you-so” or “Served-you-right” comment, is some- what tiresome even when hastily read, and more so when it must be waited for on the stage; but I do not see how the lesser characters of this play could have been less awkward or superfluous than they were.

This order of mention must not seem to set aside that constant unity of effect noted at the start. Music, scenery, cos- tume, word, acting, fell simultaneously upon the ear or eye. I speak of the mu- sic next because printed discussions must be “consecutive, not simultaneous.” And the music, both instrumental and vocal, clearly constituted Professor Morse’s greatest achievement during his years of patient effort at Dartmouth; and the greatest production of undergraduate musicians here. Professor J. K. Paine’s Oedipus music is almost as hard as the latest faddish composition of a Debussy or a Richard Strauss, or some things by Wagner. Singers and players get little help from obvious progressions or har- monies, and sometimes have to strike in almost at random, as regards the key. Whether this luscious music, so rich in tone-color—which constantly, by the way, reminds one of that fascinating and almost unknown American production, the “Phoenix Expirans” of Chadwick— is or is not on proper Greek lines I do not know and nobody knows; but it is enough to say, as Professor George D. Lord aptly put it, that it absolutely cre- ates the right attnosphcrc for the entire presentation, from the first note to the stirringly impressive trochaics at the end.

But “the play’s the thingand, re- membering how all these collaterals are a proper part of the play, we turn our memories to the spoken or sung words of the fateful tragedy itself. Here, of course, “on horror’s head horrors ac- cumulate.” A modern audience is asked to sit through a three hours’ tale of in- cest, murder, suicide, and self-mutila- tion. Not the blood-slippery stage of Webster or Tourneur, not the unsavory librettos of the modern opera, not the ac- cumulated wild woes of “King Lear,” present so fearsome a story. A recent writer in Blackwood declared that ’’King Lear” is the greatest tragedy of modern times and the “Oedipus at Colonos” of ancient. Even the latter is more re- lieved, in its banquet of terrors, than the “Oedipus Tyrannus.” Yet, if the Greek idea of Nemesis seems more repugnant to our notions of 1910 than the Calvinis- tic predestination of the sixteenth cen- tury, we must not. forget that both are terribly strong allegories of the Dar- winian law of the transmissibility of the effects of sin, or even of unconscious vio- lation of law. A generation which re- veres “The Marble Faun” may wisely turn back to this mighty elemental trag- edy of the time when it was but dimly seen that

“God hath writ all dooms magnificent, So guilt not traverses his tender will.”

The evil in the story is absolutely harm- less to the modern reader or hearer; its lesson of the third and fourth genera- tion is learnable still.

In the “Oedipus,” as in all great art, the moral, if any, inheres in the action; and all the actors, from the first line, grasped and presented this idea. Un- questionably, that action seemed to lag heavily at times; but equally unquestion- ably, the Oedipus tragedies never could have had a sprightly movement in Soph- ocles’ day. If Mr. Flint, as Oedipus, might have been “every inch a king” and shown more regality and lordly pride at the start, with less suggestion of over- hanging fate, he at least gave a symmet- rical, and at times a deeply impressive interpretation, throughout. His idea was clearly that Oedipus was more of a Richard II than a Lear. Of his amaz- ing feat of memorization of the long part without a slip, and of the unswerving unity of his rendition, the triumphant reception giyen him at the dinner fol- lowing the play was abundant proof. It is much, in the “nicely calculated less or more” of that complicated thing, a mod- ern college, to have undergraduates give wild vocal acclaim to a hero of intellect,' as well as to one of the diamond or grid- iron.

There was no flaw that I remember in the presentation of the other parts; the cold, regal Jocasta of Mr. Maynard; the haughty Creon of Mr. Defarrari; the messenger from Corinth of Mr. Johnson; the Priest of Mr. Kinne; or the Messenger from within the Palace of Mr. Adams. To the last-named, Sophocles offered- far the best opportun- ity in the whole, play; and Mr. Adams, with his fresh young earnestness and his beautifully accurate rendering of the lines, gave us all that the opportunity contained. In proportion to the length of the part, nothing more could be asked, also, of Mr. Bartlett’s Teiresias. I par- ticularly enjoyed his remarkably natural returns, when some cumulative word was needed, to the stage he had begun to leave. Mr. McAllister, as Coryphaeus, rose to the representative opportunities of his part; and Mr. Owen, as the Serv- ant of Laius, showed powers that will doubtless be more fully in evidence at the second presentation.

Looking back upon the evening, I think we are all glad that the perform- ance itself—with the exception of the valuable work of Professor Morse as conductor and Mr. Wells as first violin— was an undergraduate affair, and that ihe “professional trainer” was not called in. These youths, clad in whites, tender greens, violets, blues, reds; going to and fro before their theoretically possible • palace; now speaking and now but atti- tudinizing; singing in unison or in part- song, to the accompaniment of wood- wind or violin, retold for us one of Coleridge’s “three perfect plots,” in a way we cannot forget, and which made Dartmouth a richer place.

A word of thanks to many, on behalf of us all who benefited by their months of patient toil, may close, as of right, these scattered and imperfect notes of a listener. To Professor R. W. Hus- band, as his associates in the classical department are unanimous in insisting, belongs the greatest praise. Pie it was who voiced, as far back as the last aca- demic year, a spontaneous desire, on the part of students then taking a course under Professor C. D. Adams, to give the play. Asked to take control, the re- hearsals were in his charge, beginning as far back as last October; at first two a week, thereafter practically daily from November to the time of performance. He was'-not absent from more than four of these rehearsals, and took charge of the verbal work of the men all along. Professor C. D. Adams was also inter- ested and active from the start, devoting himself particularly to the work of the chorus. For one thing, he undertook the supervision of the writing of the Greek in no less than forty copies of the vocal score, which is printed in English and German only. Professor G. D. Lord was responsible for the plan of the stage, and much concerned himself in the color- scheme of the costuming. Professor H. E. Keyes was not less responsible for the plan and creation of the stage, Iti February, Professor Pi. E. Burton came in as dramatic trainer, and was present at fully half of the rehearsals, aided mean- while by Dr. L. C. Barret, who was the prompter at the final performance—a prompter who, on account of the won- derful memorizing, not once had to raise his voice. Helpful advice was also given by Professor J. K. Lord,j while Mrs. Charles H. Hawes, the archaeologist, sug- gested the Delphi charioteer as the basis of the costume scheme, in conformity with the arrangement of the stage. The general color-plan, at once so beautiful and accurate,, also owed much to Mrs. Hawes’ suggestion. I wish, too, that the audience could have had a nearer view of the jewels and other metal orna- ments so artistically wrought by Mr.

Charles Dunn. I am not sure, how- ever, that the chief meed of praise does not belong to Mrs. R. W. Husband, who superintended the costuming, and her- self made almost all of the costumes of the principals.

This is not a "press notice,” but it is proper to add the pleasant remark that the Dartmouth “Oedipus” will be given again at Commencement. Ido not, and cannot, interfere with the wav in which any graduate or friend of the Col- lege, then returning to Hanover, may oc- cupy the evening of the performance; but I am tempted to close by saying that unless his or her duties at that time are imperative elsewhere, to be absent from the Greek play may make one liable to the biblical characterization of a certain bird, in Job 39:17.