I recently came across an old diary, long mislaid and forgotten, which I had kept sixty-two years ago, while a student in the office of the late Dr. Dixi Crosby, and in attendance upon medical lectures in Hanover; and as I look over its yellow leaves, I find the record of many incidents in the college life of those earlier days, and, among others, the mention of numerous interviews with the late Rev. Dr. Roswell Shurtleff, who was then living, in his eighties, as Professor Emeritus in the College, where as student and tutor under the second President, John Wheelock, and afterwards as professor and college chaplain, he had been a citizen of Hanover for more than two generations.

A long intimacy between my father's family and that of Dr. Shurtleff made me a frequent visitor in his home circle, where—happily for me—I was always welcome, and while I valued his wise counsel and advice, I also enjoyed his stories of his own college experiencesy on which he so plainly loved to linger. The old gentleman was feeble from age and its many infirmities, but mentally he was alert as ever, and his memory was astonishingly acute. His reminiscences abounded in variety and in detail, always tinged with criticism and always enteraining. It was the funny side of every incident which appealed to him and to which his memory chiefly clung, and his skill as a raconteur was marked by a special charm. I regret now that I had not written down, from his own lips, many more of his college yarns, but a few which I happen to have saved, and which are here given, may interest the readers of today.

My visits to the old professor's study, in the second story of the old Shurtleff house, (which I hope is still standing) were always a delight.

It was a joy, as I entered the front hall in the winter evenings, to hear the professor at the head of the stairs, give me his welcome—"Come up to the study!" an invitation which I was quick to accept, and I climbed to the low studded room, crowded with bookshelves to the ceiling and reeking with the professor's cigars, for a pipe was his abhorrence.

A snug wood fire, burned behind the brass andirons, near which stood his writing table piled high with books and papers, (the picture is still vivid) and in front of the table sat the professor in his armchair, and close at his side another arm chair, softly cushioned, in which reposed his favorite cat, a huge, gray tabby, full of the calm dignity of ' acknowledged proprietorship, and plainly worthy of his name "Judge Lynch." The entrance of a stranger brought a momentary scowl of suspicion to the animal's face, but as his master showed no hostility to the newcomer the "Judge" resumed his purring. Whenever the cat's complacent song became too noisy, the professor laid his hand gently on the "Judge's" tiger-like head with: "Linky, be quiet, not so loud, Linky!" and the conversation went on.

One evening, as I entered the study, the doctor closed a big octavo in which he seemed absorbed, saying, "Come in! come in! glad to see you. I am just finishing Gibbon for the seventh time, and he grows richer with every reading!"

The old professor easily drifted into reminiscences of his college days, and was fond of dwelling upon the personal characteristics of his associates in the faculty. "I never saw President Eleazar Wheelock," he said, "he died shortly before I came to college, but with his son John I was closely associated. The first Wheelock had some peculiarities. He wrote in his will 'I give and bequeath to my son John, Mink Brook!' and in his 'Narratives' sent home to his patrons in Scotland, he writes, 'I have enclosed 2,000 acres of the wilderness for pasture for my cattle, to the end that I may have them ever within my reach."

"The second Wheelock was in physique tall and very spare but exceedingly muscular. His nose was a perfect quadrant. He was extremely neat in his dress, and always wore smallclothes with knee buckles, and a cocked hat . He was a ready talker, profuse in words, but not always forcible ones. I recollect one night, quite late, while I was tutor, I was called up by the President and Professor Smith to accompany them to No. 3 Dartmouth Hall (which was long afterwards the Tri Kappa lodge room), to break up a carouse among sundry students. I demurred, not counting myself as of full authority with the faculty, but at their insistence I finally went with them and climbed to the third story of old Dartmouth Hall guided by the noise in room No. 3. On reaching the door, which was closely locked, the President knocked and loudly demanded admittance, which was of course refused. The President then turned to me and said, 'Shurtleff, shall we force the door ?' I replied, 'Since you have come for the purpose Mr. President, don't you think you had better complete your job!'. Whereupon the President stepped back a few paces for a run and with a mighty kick from his muscular legs the door flew open, disclosing seven students in unseemly costumes and attitudes, 'and in various degrees of intoxication. The besieging party at once entered and took possession. One yonng man was in bed, another was kneeling in the middle of the floor, unclad except for a jacket, indulging in many extravagances of word and act. As the faculty entered, the devotee looked up and shouted, 'What! you here? Well, I'm not half so drunk as I have been!' Another of the revellers. now emerged from the closet and began an abusive speech to the invaders. Professor Smith seizing him by the arm, said sternly, 'Silence! Young man, don't you see that this is President Wheelock ? The fellow replied with a shout, 'Ah! President Wheelock! I m happy to meet so distinguished a character! and sir, I am no less distinguished, nor do I acknowledge any superiority 'Yes sir,' said the President calmly, 'Bacchus was ever wont to reckon himself the noblest of the gods'!"

"The president was in the habit of commenting upon the essays read by the students at evening chapel. His fluency in extempore speaking was ccfnsiderable, his voice full and sonorous and he specially piqued himself on his wellrounded periods, which often fell quite flat upon student ears, which are apt to be critical. I recollect that one evening at chapel in my senior year I read, in my turn, an essay on 'The influence of climate upon human life and character.' I was followed by another student whose subject was, 'The influence of climate upon animals.' The President commented in his usual way upon the two essays and added sonorously, in conclusion, 'lt is therefore evident, that the dog can live in the temperate zone, the dog can live in the torrid zone, and the dog can live in the frigid zone, but of course some dogs are not so large as what some other dogs are!' This was said very seriously and impressively, and was received by the students with perfect gravity."

Dr. Shurtleff was a member of the faculty during the long-ago dark and troublous period of Dartmouth's struggle, in the quarrel between College and State, and in the litigation which followed. This was the once famous "Dartmouth College Case," in which Daniel Webster came so nobly to the defence of his alma mater before the United States supreme court, and saved "the little College" from threatened extinction. My old friend, the Professor, was then in the thick of the fight against President Wheelock and he always mentioned this subject with much feeling and not without a degree of bitterness.

I regret that, of all the host of Dr. Shurtleff's reminiscences so interesting to hear from his lips, and so valuable a part of the history of Dartmouth in its earlier days and struggles, my record should be so meagre, but. I am too near the threshold of my own eighty-sixth year, to recall definitely any of his narratives beyond the scattered fragments which the old diary supplies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE RECENT GROWTH OF DARTMOUTH A PARTIAL RECOVERY OF POSITION

December 1911 By William Jewett Tucker, '61 -

Article

ArticleIt is gratifying to note the virtually

December 1911 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1911 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1907

December 1911 By Thacher W. Worthen -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1911 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY ACTIVITIES

December 1911

Article

-

Article

ArticleDEBATING

February, 1912 -

Article

ArticleFOREIGN SCHOLARSHIPS OPEN TO U. S. COLLEGE STUDENTS

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleFall Courses

December 1942 -

Article

ArticleTHEY'RE OFF!

April 1956 -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Jul/Aug 2004 By Susan Hamilton Munoz '92 -

Article

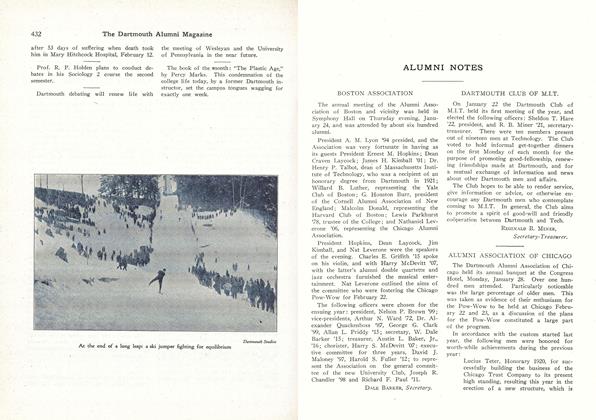

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATION OF CHICAGO

March, 1924 By Warren D. Bruner