THE RECENT GROWTH OF DARTMOUTH A PARTIAL RECOVERY OF POSITION

December, 1911 William Jewett Tucker, '61THE RECENT GROWTH OF DARTMOUTH A PARTIAL RECOVERY OF POSITION William Jewett Tucker, '61 December, 1911

The editors of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE very properly ask for the opinion of the alumni in regard to the vote of the Trustees in which they make known their policy concerning the numerical growth of the College. In the expression of opinion thus called for it may be of aid to the younger, and to some of the older alumni, to have before them certain facts with which they are not familiar. Of course the decisive questions affecting the development of the College, which confront in turn each administration, are strictly educational, questions, that is, of educational aims and facilities—the size and quality of the teaching force, the adequacy of the material equipment, the standards of character, scholarship, and manners. But an historic college also stands at any given time in a very definite and vital relation to its history. Its chief inheritance or endowment is that of the spirit which caused it to be and to grow, but it has likewise and in consequence an inheritance or endowment of reputation, standing, and position. Again it is to be said that numbers do not constitute any sufficient basis of comparison in estimating the reputation or position of'a college, while at the same time we recognize the obvious fact that numerical increase is one of those normal expressions of vitality and growth the absence of which always requires explanation.

Among the nine colonial colleges of the country there" were four which drew upon the same general constituency, and which for a hundred years, 1770-1870, moved on together in compara- tive numerical equality—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth. Dartmouth was the last comer in the group, but from the very beginning it showed surprising vitality. During the first twenty-five years of college existence Harvard (1642) graduated 159 men; Yale (1702) 170; Princeton (1748) 354; Dartmouth (1769 ) 476. When Harvard was founded, and even at the founding of Yale, the population was meagre: on the other hand Dartmouth was located at a point remote from population. It was for long time literally a "voice crying in the wilderness."

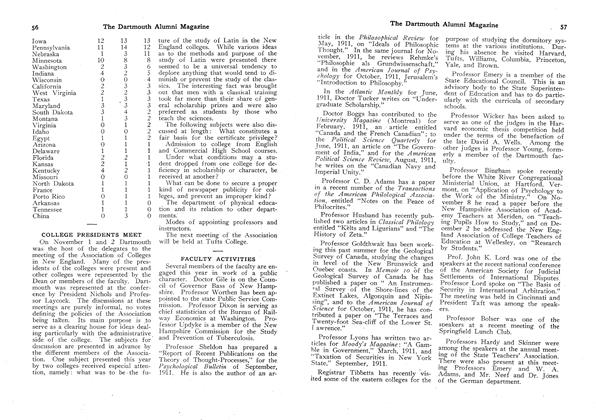

The period from 1790, beginning with the first unbroken decade after the War of the Revolution, to 1860, including the last decade before the Civil War, a period of seventy years, was the distinctive period of the American College. Academic conditions were practically the same in all the colleges. None of these had made any advances toward, university life; and it would hardly be claimed that the schools which took the name of universities, prior to the Civil War, were above the grade of the New England college. Within this period Harvard graduated a few more than 4,000, Yale a few less than 5,000, and Princeton and Dartmouth about 3,000 each. This general ratio was distributed equally throughout the seven decades as may be seen from a comparison taken for the first two decades, and for the last two decades of the period:

1790-1800 1800-10 1840-50 1850-60 Harvard 394 449 632 870 Yale 295 518 926 1009 Princeton 240 328 649 677 Dartmouth 362 337 591 639

After the country recovered from the effects of the Civil War educational conditions changed rapidly. Harvard led the way in the advance with new and broader methods, supported by the ample resources of its alumni. The most marked advance came through the clearer recognition of the scientific method in all educational training, and especially in the larger development of the sciences themselves. Gradually the colleges in the group, with the exception of Dartmouth, took on the functions, as well as the name of the university — Princeton, through its graduate school, as late as 1896. But the noticeable fact in this advance was the persistence of the college idea and form. Harvard College, Yale College, and Princeton College are today distinct entities, especially in the minds of the alumni, young as well as old, as they were before university functions were assumed. In this respect the development of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton has been in appreciable contrast with that of Columbia, as it has been in marked contrast with that of the universities of the West. The comparison, therefore, can be continued on the college basis, taking ac- count only of the fact that the B.S. degree, or its equivalent, now comes into the reckoning on equal terms with the A.B. degree. Princeton confers at present in addition to the A.B. and B.S. degrees the degrees of Litt.B. and of C.E. for undergraduate work.

The following tables show in detail comparative results from 1870 to the present time:

No. OF GRADUATES BY DECADES FROM 1870-1900 1870-80 1880-90 1890-1900 Harvard 1579 2143 3913 Yale 1603 1900 3588 Princeton 952 1008 1706 Dartmouth 754 668 735

Number of students in entering classes for past five years (including those who graduated in 1910 and those still to graduate) :

ENTERING CLASSES IN 1907-08 1908-09 1909-10 1910-11 1911-12 Harvard 633 623 664 671 744 Yale 778 775 731 780 785 Princeton 328 347 362 345 394 Dartmouth 357 334 309 398 426

This enumeration of vital statistics in the history of the college has been given to show that its natural condition has been that of growth. The college began in a remarkable assertion of vitality, it maintained itself in relative growth for nearly a century, and now, after a brief period to which reference will be made, it is in the process of recovery. The Trustees have before them, as they have had for some years, not an artificial but a vital problem. It is proper to say that the action which they have announced is in no sense unconsidered action. The following vote is on record under date of December 21, 1906: "The President having submitted a report upon the effect of the numerical growth of the College upon its educational policy, after full discussion it was voted, that it is the purpose of the Board both in its educational and financial policy to provide so far as possible for the natural growth of the College."

There have been three distinctive and somewhat peculiar incentives to the growth of Dartmouth. First, the spirit of its founder. No other college of its time began under such extraordinary leadership. Through Eleazar Wheelock the pioneer spirit was implanted in the College. It has been, and is still operative, expressing itself in ways which naturally lead to growth.

Second, the note of nationality which was struck early in its history. The Dartmouth College Case (1819) not only introduced the College to the country, it seemed to identify the College with the interests of the country. The reaction also of the "Case" upon the College itself has been greatly to its advantage as an antidote to provincialism. The mind of the College caught something of the scope and movement of the mind of the great advocate, who throughout his whole career thought in terms of nationality.

Third, the comparative isolation of the College which has caused the wide dispersion of its alumni. Within a radius of a hundred miles from the College there have been few places in which the graduates could afford to establish themselves. As often as the question arose, where shall one go? it was as easy to decide to go far as to go near, to seek the great centers as to stop in the smaller centers. In consequence it may fairly be said that the influence of Dartmouth alumni has been out of proportion to their numbers. Many a man who would have been lost in the populous environment of the College, had such existed, has achieved, distinction and influence elsewhere. This fact of unusual influence, coupled with that of unusual loyalty, accounts in part for the numerical growth of the College far without the ranee of its immediate activities. It explains in part why out of 1226 students now in the College proper, 860 come from outside the northern New England states, and 378 from outside New England, representing thirty-two states and countries.

Reference has been made to a period in which Dartmouth did not hold its relative place numerically. This was the period when the alumni of the other great alumni colleges, with which Dartmouth was grouped, rallied to the financial support of their respective colleges in their advanced movement. At this time and in this necessity the dispersion of the alumni of Dartmouth worked to its great disadvantage. Very many of the wealthy alumni of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton were close at hand, residents of Boston, New York, Philadelphia. They could see the necessities of their colleges. They could see the opportunities before them. Most of the wealthier alumni of Dartmouth, more remote from the College, had become identified financially with interests in their own localities. They were not available for timely gifts. How much such gifts would then have availed can be seen from the effect of more recent gifts. It is not difficult to see the effect upon the growth of the College of the collecetive action of the alumni in rebuilding Dartmouth Hall, in erecting Webster Hall, and in establishing .the new gymnasium. It is impossible not to see the effect of the timeliness, as well as the generosity, of the gifts of Edward Tuck for purposes of instruction, when midway in one administration he gave half a million for this object, following it with the gift of the building which bears his name, and when at the beginning of the next administration he repeated the gift for the like object in a way to make it peculiarly stimulating. Nor can one, who is at all conversant with the inner life of the College, fail to see the effect of the memorial gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Parkhurst in facilitating and giving increased efficiency to the whole work of administration.

The failure of the College to receive adequate gifts at a time of general educational expansion, occasioning a numerical level as compared with the gains of its oldtime companions, more fortunate financially, is certainly not an educational reason for the reduction or limitation of numbers. The plain alternative to the allowance of a healthy numerical growth would seem to be the invention of an educational policy which should guarantee better educational results through the reduction or limitation of numbers, without incurring thereby the danger from specializiation or from provincialism.

No. OF GRADUATES BY YEARS FROM 1900-1909 1900 1901 1902 1903 1904 1905 1906 1907 1908 1909 Harvard 495 561 541 609 588 562 545 543 509 500 Yale 456 395 421 447 461 452 510 571 611 530 Princeton 199 210 252 229 277 266 249 264 221 260 Dartmouth 120 119 136 134 125 141 162 200 192 203

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIt is gratifying to note the virtually

December 1911 -

Article

ArticleREMINISCENCES OF PROFESSOR SHURTLEFF

December 1911 By Josiah Whitney Barstow, '46 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1911 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1907

December 1911 By Thacher W. Worthen -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

December 1911 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY ACTIVITIES

December 1911

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY NOTES

June, 1912 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH RECEIVES REQUEST OF $218,642

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1957 -

Article

ArticlePosthumous Tribute Paid To Bob Williamson '34

MAY 1966 -

Article

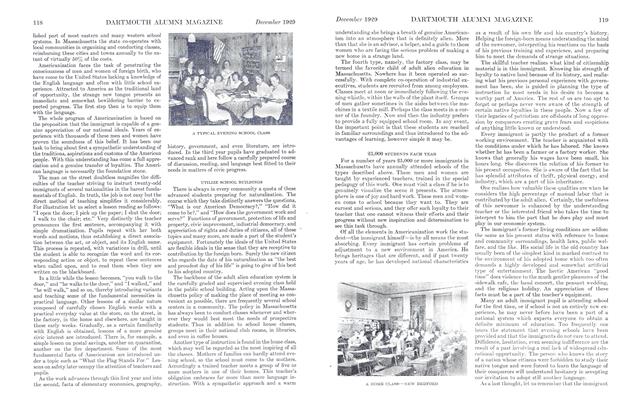

Article25,000 STUDENTS EACH YEAR

DECEMBER 1929 By E. Everett Clark -

Article

ArticleWILLIAM HOOD '67 Chief Engineer of the Southern Pacific Railroad Lines

March 1919 By Robert Fletcher