Senior Fellow Names Books Read During Year Describing Value of Each to Him

THIS MONTH I have asked Rodger S. Harrison of New York City, a Senior Fellow who has been reading under my intermittent guidance during the year, to give to the alumni some benefit of his experience, and to tell briefly of some of the books which really meant something to him. Save for my list of suggestions, then, the whole column for this month is his. My thanks to him not only for writing this but also for his friendly cooperation through a somewhat difficult year owing to illness. Mr. Harrison's article follows:

"Simply the chance to read for the better part of a year has been a real experience for me, and a valuable education in itself. Back in September, under the guidance of Professor West, to whom I would like to express my appreciation for this opportunity of humbly "pinch hitting," I drew up a reading list of outstanding books of all times and all countries—a pretty big order, to be sure, but I think we worked out a fairly comprehensive literary vision of about seventy books. There were obvious gaps. For my part I selected books, references to which I had continually run across; books which fall under that "by-golly, someday-I'll-read-that-book" category.

"The books I mention here, therefore, are by no means new releases—their titles at least will be familiar to all. I'm going to comment in a very cursory manner on six or seven of these books which have made a real impression on me this year. It is difficult and perhaps foolhardy to attempt an interesting review of some of the classics, because there is already so much scholarly material regarding them. And furthermore, your chances are about a hundred to one that whoever you are writing for has read the book more thoroughly than you have. But for that one procrastinating "by-golly" man this may be of some interest. For the other ninety-nine: well, the least I can hope is to sweep from your minds a few cob-webs which may have accumulated since you read the book.

"Some evening after a train ride in the smoker, where each chap could always go one better and the first liar didn't stand a chance, try reading Lucian's True History. Lucian is the liar of all liars, except that unlike the smoking car boys, he prefaces his story by stating very frankly that, "This one thing I confidently pronounce for a truth, that I lie!" With that blunt admission he begins a narrative of most traordinary adventures, so ingeniously and beautifully worked out in detailed verisimilitude that one is very apt to be entranced into their acceptancy as truth. The book is the precursor of all fantasies; the undoubted inspiration and model for Cervantes' Don Quixote, Voltaire's Candide, Raspe's marvelous travels of the Baron Munchausen, and Swift's Gulliver'sTravels, to mention only a few of the more famous imitators. Lucian, undoubtedly annoyed and perplexed by the way people were taken in by Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (and especially Herodotus), gave full reign to scepticism and satire in a delightful parody on all "true" historians.

"Abruptly jumping to another extreme, The Republic of Plato is not a book to browse in casually. You must imbue yourself with that feeling of a mountaineer, who, dauntlessly gazing up from the valley at a towering, rugged peak, takes a defiant hitch in his belt before beginning the ascent. The Republic is deep and involved, and it's no good to try to skim from one point to the next, because, like geometry, the principles mean nothing without the premises and corollaries upon which they are constructed. But don't be frightened with the mere aspect. The energy put into the reading of the book will be many times repaid by the satisfaction derived from contact with the mind of one of the greatest of all philosophers.

"The opening books consist of a controversial symposium regarding the question: What is justice? The keen analyzing intellect of Socrates is illustrated, for this is assumed to be direct quotation from him. It is mainly wordy warfare in which the philosopher ingeniously forces his disciples into verbal admission of the truth of certain statements without, however, actually changing their deep-seated convictions to the contrary. Being accused of this, Socrates, who now becomes the mouth-piece for Plato, proposes to construct a model community, because pure justice and injustice can be more easily located and evaluated on a large scale than in an individual case. Having found and defined community justice, the disciples will be better equipped to examine the relative merits of justice and injustice for the individual. The development of this scheme occupies the major part of the Republic, and is no doubt the real purpose for the writing of the book. Plato's ideas regarding religion, education, politics and government, ethics and morals are certainly worth everybody's attention. The intellectual aristocracy is for Plato the only solution for harmonious living. Certainly the modern mess in which democracies, monarchies, and dictators are stewing bears out Plato's wisdom in a remarkable manner.

"Benvenuto Cellini's Autobiography is a tribute to unabashed braggadocio. His tempestuous life is related as vividly as any tale of fiction; indeed, there can be little doubt but what it is highly fictional. Cellini, a fine goldsmith, but not great as a sculptor, owes his reputation, both in artistic and literary circles, to his Autobiography. He is all blood and thunder and prevarication. The book is a graphic rendition of the true artistic temperament. I do not believe Benvenuto consciously boasted. He was plagued with a gift of colorful exaggeration, and after repeating some quite ordinary adventure several times it assumed gigantic proportions. But I am sure that Cellini himself was convinced of his veracity.

"He cannot fail to appeal to young men, who are prone to such day dreams as, "storming down the staircase, and when I reached the street, I found all the rest of the household, more than twelve persons; one of them had seized an iron shovel, another a thick iron pipe, one had an anvil, some of them cudgels, some of them hammers. When I got among them, raging like a bull, I flung four or five of them to the earth," (boy o boy!) "and fell down with them myself, continually aiming my dagger now at one, now at another," to quote directly from one of the thrilling episodes. What a man! That's life—what I mean! There is an unfathomable charm about the boasting of Benvenuto Cellini which will capture you.

Another book, which I venture to say is the most famous of all autobiographies, is Rousseau's Confessions. Jean Jacques is one of the most engaging of all literary characters, because, like Cellini and a few others, but unlike so many men of letters, he had an interesting personality as well as a fertile mind.

"The Confessions start with the avowed purpose of presenting "my fellow mortals with a man in all the integrity of nature, and this man shall be myself," but soon becomes a justification and defence against the accusations of his enemies. Extremely sensitive, and obsessed in his later years with acute delusions of persecution, Rousseau lived a very unhappy life. This is reflected not only in the actual word content of the Confessions, but also in the general melancholy, and sentimental atmospheres which saturate the book, and from which the reader cannot escape. He wrote a psychological document, leaving little or nothing to conjecture. This utter frankness was offensive to many of his contemporaries. People who had admired his Emile, and Social Contract could not understand how the author of such fine and enlightening books could live a personal life of such wretchedness and sin. The publication of the Confessions did Rousseau, the man, far more harm than good, but it made Rousseau, the literary figure, immortal.

"For lively reading of a more fictional character, I found Kingsley's WestwardHo! most enjoyable. It is a historical novel, which depicts Elizabethan England as its background. The book was written as a tribute to the valor and spirit of the British maritime buccaneers of Queen Bess's reign. The portrait of sixteenth century England is a sincere one, and the facts the author enunciates are no doubt authentic. The rivalry of the English and Spanish in religious issues as well as competitive commercial imperialism is also well handled. There is, however, a certain air of artificial gallantry in the concatenation of events as well as in the character portrayal. The novel was not molded around the characters; they were made to fit and aggrandize the spirit of the novel, which gives the feeling that they are pen productions rather than real people. Amyas Leigh, the hero, is a little too perfect and all-conquering, and Rose Salterne is an obvious misfit, her character and temperament belonging to the more chivalrous days of Cromwell. The story is slow in getting started, but once under way it has plenty of action. For an enjoyable portrait of Elizabethan England and her seafaring rovers, Westward Ho! is hard to beat.

"Coming along to more contemporary times, Leo Tolstoy has given us several great books, most popular of which is probably Anna Karenina, with War andPeace running a close second. They are both similar in their description of society in Czarist Russia. Anyone with a historical bent will find War and Peace just as enjoy- able and perhaps more valuable than Anna Karenina. War and Peace deals with Russian society during the period of Na- poleon's march to Moscow. Besides follow- ing the lives of the various characters, most important of whom is Pierre Bezukhov, War and Peace is a treatise on history and the historical method. The author takes issue with historians, illustrating that no two historians will relate facts in the same way. They are prejudiced by their na- tionality, and will interpret facts accord- ingly. Tolstoy ridicules and questions the influence men have over their own lives, or over the lives of others. He demonstrates pretty convincingly that there is another force guiding man's destiny, and although men may apparently act ing to their own volition, their actions are dictated by many inter-related and inevitable circumstances. This historical analysis breaks up the continuity of the action to some extent, but obviously the treatment of history was foremost in Tolstoy's mind as he wrote War and Peace; the action is merely intended to illustrate his theory of history.

"Generally speaking, War and Peace is an interpretation of the elements of human emotions, individually conflicting and collectively pulling together; it is a kaleidoscopic whirl of Moscow society in all its whimsicalities and superficialities; it is a philosophy of life and men's motivations, thereby making it more than a picture of Russia:—a panorama embracing all of mankind.

"For an active contemporary author, I suggest John Dos Passos. His style is somewhat comparable to that of Hemingway, Cain, and Steinbeck, but perhaps in a closer view it more resembles James Joyce. Yet I found Ulysses a sort of enigma and a task, whereas U. S. A. is a real pleaure. U. S. A. is a trilogy of three novels: The42nd, Parallel, Nineteen Nineteen, and The Big Money. Introduced are a series of characters, the relations of several of whom become combined as the trilogy progresses. The Newsreels, thumb-nail biographies, and Camera Eyes may at first be confusing, but they all serve to illustrate the tempo of United States' life which the author is trying to portray. The Newsreels can well be skimmed over, just as we watch them flicker before us at the movies, but I found the intermittant biographies and Camera Eyes very interesting, not only in themselves as gems of forceful prose, but also in aiding in the creation of a cross-section American portrait. The author fails to a certain extent in depicting United States because of the general conformity of all the characters to a pattern. Dos Passos gives us many characters, but they are all of lower class background undergoing a pretty stereotyped metamorphosis. He entirely neglects the bourgeoisie and aristocracy, such as it is in this country. However, this deficiency is made up somewhat by the informal biographies which deal almost entirely with more famous people of well-to-do means, such as Ford, Hearst, J. P. Morgan, and others.

"U. S. A. is just what its title indicates, and the literary form of the three novels as well as the subject matter, is a commendable, though perhaps not flattering, portrayal of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century United States."

RODGER S. HARRISON '39

PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

June 1939 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

June 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Article

ArticleCarnival at Commencement

June 1939 By MILDRED L. SAUNDERS

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

August 1942 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksSUCH IS LIFE

June 1952 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksSIDEWHEELER SAGA

July 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Tops Goal

JULY 1963 -

Article

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

March 1981 -

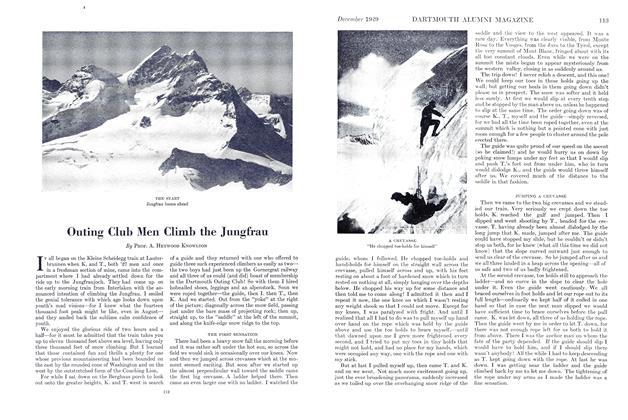

Article

ArticleOuting Club Men Climb the Jungfrau

DECEMBER 1929 By Prof. A. Heywood Knowlton -

Article

ArticleNotes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 By R. H. R. -

Article

ArticleSpring Schedules

March 1960 By RAY BUCK '52