The ethnological collection of the College has been entirely re-arranged and is now in course of being labelled. It seemed therefore an opportunity to take stock, and the editor has asked me to make a report.

Among museums of the country, ours is, of course, a miniature one, containing as it does less than 3,000 articles. However, it is remarkable for the many countries and peoples of the world which have contributed to it.

Its early history is merged in that of the "Museum and Cabinet," founded by President John Wheelock, although it is doubtful whether many of the curiosities which he gathered on his European trip, besides the books, were saved from wreck.

According to the College historian valuable foreign curiosities and an "albatross head" were given as early as 1791 by the Rev. Jeremy Belknap and Capt. Perkins. In 1796 gifts from E. H. Derby, of Salem, Mass., included a stuffed zebra. This was apparently as great an asset to the College as was Yale's two-headed snake. This embodiment of the fame of the College, in the words of Professor J. K. Lord "left for other and unknown pastures." It has been succeeded in the Temple of Fame (and not in the Museum, as might have been gathered from a recent article in the Boston Transcript), by Daniel Webster.

It is not yet possible to trace any of these early gifts, though some of the objects on the shelves from the South Seas may be part of the gift of Heman Harris 'in 1799, articles probably brought home by Captain Cook. In fact a small piece of oak wood from the captain's ship "Endeavour" may very well be one of these.

In addition to Professor Frederick Hall's large mineralogical gifts, from seventy to eighty years ago, the ethnological collection houses several of his curios gathered in the Mediterranean area, e.g., pottery, terra cotta heads, tesselated pavement from Herculaneum, and figurines, mummy wrappings, etc., from Egypt.

The most valuable gift ever made to the Museum was that by Sir Henry Rawlinson, to the Rev. Austin H. Wright ('30) through the efforts of the professor of chemistry and pharmacy, O. P. Hubbard, a man of wide interests. Professor Hubbard was aware of the epoch-making discoveries, archaeological and philological, being made in Babylonia 'and Assyria, and in 1852 wrote Wright who was then working as a missionary in Urumiah (the scene of recent massacres), to ask him to obtain some inscriptions, if possible, for the College. His very good friend, Sir Henry Rawlinson, promptly and generously responded, and the result is that Dartmouth possesses the best sculptured slabs from Nineveh in the country, saving those recently acouired by the New York Historical Society. They represent the great warrior king of Assyria, Assur-nazirpal (885-858 B. C.), with his high officers ; and the inscription gives a glorified account of his warlike activities, which no modern Official Press Bureau could equal.

We have seen that the early gifts are hard to seek, owing to the many vicissitudes of after years, such as the great and memorable struggle with the State, and the repeated removals of the collection. Much must have been lost or destroyed in its progress from Dartmouth Hall to Reed, from Reed Hall to Culver, and finally to its present resting place in the Butterfield Museum. It& is, therefore, not surprising that when the writer came to re-arrange the collection some strange wanderings of objects had taken place. A praise-worthy effort had been made to keep them in geographically distinct areas, but not always with success. From an ethnological point of view there was an ominous overlapping of the Pacific Islanders and the Plains Indians; a Zulu whip was found, so-to-speak, in the Middle West; the fragment of the keel of Captain Cook's ship was, perhaps, where it was most at home, in the Pacific; but a portion of the label, with a mobility worthy of the great Captain himself, was keeping company with the stone implements of New Hampshire!

In re-arranging and labelling the collection, a tabulated plan of the distribution and general nature of the contents of each case will be prominently displayed. On each case the geographical area or areas will be indicated by colored maps attached to the case. Alongside of these are now being placed general outlines of the culture of the peoples and tribes whose handiwork is exhibited. Finally each article or class of articles will have a label. Thus we approach the ideal museum which is said to be a complete collection of labels illustrated by objects.

The collection has been divided into four parts, and these again have been subdivided geographically. The main divisions are as follows:—

I. Stone implements, mainly from America, a few from Hawaii, Fiji, and New Guinea, together with casts of prehistoric implements of Europe.

II. Pottery, chiefly from sites in North and South America.

III. Skeletal material from Florida, etc.

IV. Various objects illustrating the daily life of the many peoples, e.g., baskets, clothing, tools, weapons, ornaments, models from all parts of the world.

Whereas the collection is comparatively rich, as it should be in New Hampshire stone implements, it is very poor in stone tools from the West and Middle West. In fact there is little from those very regions, which yield us the finest specimens of flaking,—partly because of their more suitable material,— save Dr. Butterfield's ('39) gift from Kansas. Our New Hampshire implements, which we owe, almost entirely to the late W. C. Fox ('52) of Wolfeboro, N. H., include some excellent stone gouges (almost the only stone tool that is of the same type as those in Europe, and therefore regarded by some as a prehistoric link), and several of those long, sausage-shaped pestles, which are so heavy that we may believe Schoolcraft when he wrote that the Indians of New Hampshire suspended them from branches of trees to avoid the labour of lifting them repeatedly. From New Guinea come the most beautiful polished nephrite stone celts or jade axes, one of which has been used to pound sago and the other, with thin blade elaborately mounted, as a ceremonial axe and as currency. To Professor-Emeritus C. H. Hitchcock the museum owes many objects and among them heavy stone adzes, pounders and net sinkers from Hawaii.

The collection of pottery leaves much to be desired, and perhaps some Dartmouth men could help us in this respect with gifts of Indian pottery. I believe there are only two small pieces of Hopi work in the museum, which we owe to the American Museum of Natural History, New York, and for the rest only some pots and bowls from Nicaragua and a Missouri mound, besides a few various fragments.

The skeletal material is scanty and although family skeletons in cupboards are said to be common, we can scarcely expect many Indian skulls from the attics of members of the College. I understand one alumnus of the College, William Stickney ('00), nobly risked his life in the cause, and the result is that the museum owns an Eskimo skull rescued from cold storage in an Arctic grave.

The last division of the Dartmouth Ethnological Collection is the largest, and merits more detailed mention. As the result of a recent visit of Professor Patten to New Guinea we owe to him and the Biological Department a valuable addition to the South Pacific exhibit; and perhaps this is now the most complete of all. Particularly noticeable are the 27 hunting and fishing arrows of varied design—some tipped with cassowary's claws,—and the wooden shields decorated in red, white, and black and illustrating some of the stages in the evolution of geometric designs from the human form. From the rest of Papuasia, Polynesia, and Micronesia, are women's grass fringe petticoats in varied fashions, handsomely carved black wood clubs, some with decorative designs picked out with lime, (Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Samoa) ; fibre cloth with stencilled leaf pattern (leaves actually having been employed), and the wooden bark-beaters employed in their manufacture. The bark-beaters came from Hawaii, and it is interesting to speculate why similar tools are found in tropical America and then again nowhere else along the Pacific coast until you come to Washington and British Columbia.

Owing to the generosity of the American Natural History Museum, Filipino arts and crafts are represented by a great variety of baskets, bamboo snares, pina, husi, and other varieties of native cloth, a kris, with its sinuous blade, a native rice mill, models of outriggers, etc. To the same source we owe also fur garments, ivory carvings, etc., of the Chukchis of the far Northeastern coast of Siberia. From Oriental countries farther south, Japan, China, and Burma come articles illustrative of domestic life, e.g., utensils for the preparation of food, betel nut (for chewing), boxes, monastic and secular garments, small shrines, a complete suit of Japanese armor, etc. Several articles illustrating the primitive life of the Ainus in the northern island of Japan form a valuable part of the collection.

South Africa, or /more precisely, Zululand, is represented by assegais, a shield of buffalo hide, whips of raw hide, wooden head rests, etc.

In addition to the contents of the Hall cabinet mentioned above there is from Egypt the mummy of a girl in good preservation—although the wrappings have suffered—who lived in the XXIVth dynasty (late in the VIIIth century B. C.). This was given to the College by the late Professor W. T. Smith.

The collection is sadly wanting where it should be strong, namely, in objects illustrating the life of the American Indian. One quarter of the sole case devoted to them is occupied by Alaskan articles, chiefly from the Aleuts. These consist of waterproof coats made from the entrails of seal, models of skin boats, a war boat equipped with men and weapons, and fishing tackle. Various articles of the Plains Indians, particularly of the Nez Percés tribe, moccasins, tobacco pouches, dance rattles, a Pawnee chief's complete outfit, Cherokee and other bows' and arrows, whips, etc., complete the contents of the case.

Perhaps some who read this may know of Indian relics or East Indian curios stowed away in attics, no longer valued, their associations for the original collector lost with him. If so such may be assured of an honorable home in the College collection for their gifts, and they will prove of value both in class work and in the widening of our horizon. The department has no funds with which to purchase objects, and therefore has to rely upon gifts. During the last twelve months many gifts have come from students and members of the faculty. C. K. Butler ('14) presented the College with a banner stone (the only one it possesses) and 134 arrow and spear heads; and of the class of '15, P. K. Alexander, C. B. Jordan, D. H. Markham and T. R. Mason have added to our Indian material as well as W. W. Banton, G. P. Kreider, and H. S. Turtle of the class of '16.

The writer looks forward to the time when the College will have, not only, a larger ethnological collection but a College Historical Museum. It seems highly desirable, that this means should be& available for giving our Dartmouth men a historical background, an appreciation of the true Dartmouth traditions, and an insight into the real Dartmouth spirit, which has made the College what it is. When one reads the pages of Professor Lord's history of the College, one is fired by the splendid self-sacrifice of those great benefactors who gave not money or primarily money but their health and life for Dartmouth. It is too much to hope that every student will read the volumes of Professors Chase and Lord, when the newspaper columns on baseball are so attractive, but if the College possessed a small museum with articles, documents, and varied objects owned by or intimately connected with the early alumni of the College it might prove both an _ attraction and an important link with the past. If a fireproof room _ were provided, there are already objects which belonged to or were used by Eleazar Wheelock and Daniel Webster scattered about the College, some of them in safe keeping from fire and the public gaze, which would form the nucleus of such a collection: and I anticipate that there would be a generous response from the alumni in the shape of articles which would connect with past graduates and would serve as links with the past and mark stages in the history of the College. Books, prints, and photographs, not only of the College but of the immediate neighborhood, in which all Dartmouth men have been interested, might also find a home in it. This very thing on a much more complete scale has been done by the peasants of Finland throughout their country, and we might well emulate the most industrious and the most literate people of the Russian Empire.

Besides the exhibits already cited, there exists a Cypriot collection, the gift of the late Mrs. Emily H. Hitch-cock. This formed a small portion of the wonderful collection made in Cyprus by General Cesnola, the bulk of which is now in the Metropolitan Art Museum, New York. The Dartmouth portion of it which has not yet been placed on exhibition, comprises some excellent prehistoric bronzes, daggers (c. 2,000 B. C.), mirrors, painted pottery of various prehistoric periods, Roman iridescent glass, and some statuary, in all probably one thousand pieces.

Visitors to the College this summer will be able to view a small loan collection of Babylonian clay tablets. Some of these date to the time of Abram (c. 2,000 B. C.), several 300 years earlier and some belong to the reign of Nebuchadrezzar and the Persian conquerors, Cyrus and Cambyses. The tablets with their cuneiform inscriptions consist mostly of temple receipts for offerings of animals and fruits. Some have been sealed by the scribe to prevent fraudulent alteration. Others are contracts and letters. Two of them retain their envelopes of clay, reminding us that an efficient postal system existed in the time of the great king, Khammurabi (c. 1950 B. C.) and centuries earlier in the reign of Sargon of Akkad. Another is a promissory note and yet another is a round tablet, a schoolboy's exercise in which he has diligently repeated his copy. One of the favorite morals so copied was "He who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise as the dawn." Nearly forty of these are the property of Dr. Edgar J. Banks who excavated Bismya for the University of Chicago, and he offers them to the College for $100. The rest are on loan by the writer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleQUERIES OF AN ALUMNUS AS TO THE TENDENCIES OF UNDERGRADUATE LIFE AT DARTMOUTH

June 1915 By Henry L. Moore '77 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF TRUSTEES

June 1915 -

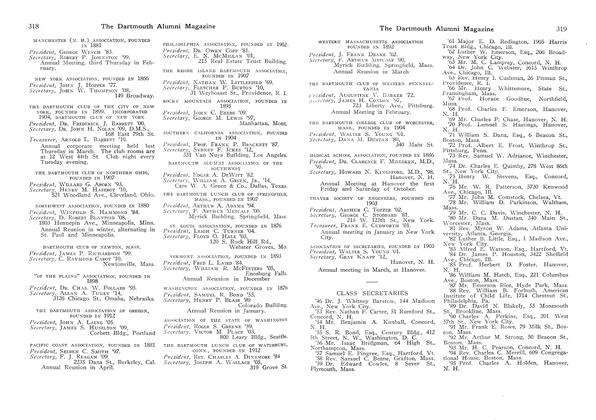

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1915 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1915 -

Article

ArticlePresident of the Alumni Association

June 1915 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

June 1915

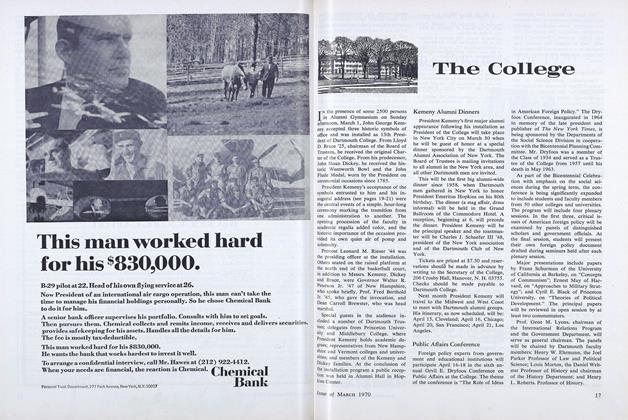

Article

-

Article

ArticleNewcomers Among Our Contributors

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleDean Bill Delegate

November 1940 -

Article

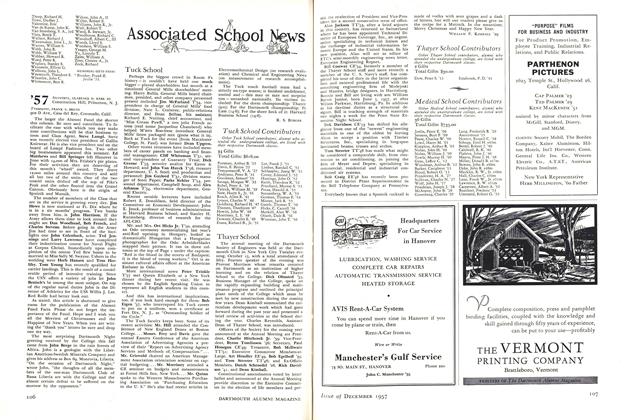

ArticleMedical School Contributors

December 1957 -

Article

ArticlePublic Affairs Conference

MARCH 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Alumni Council's

MARCH 1970 -

Article

ArticleCoping Mechanisims

Nov/Dec 2005 By Lauren Zeranski '02