THE roots of the matter are anchored in self-defense. When I went to my enrollment interview, the first question the Dartmouth alumnus asked me was "Do you play football?" Since I stand six-feet five and weigh 200 pounds, this question and the one which followed - "How about hoops?" - were really not out of line. By the time the alumnus had questioned me about ten major sports and my willingness to play women's field hockey, all the while subverting my attempts to learn more about Dartmouth, I realized that if we were to get anywhere, I would have to come up with an athletic interest.

I had often seen pictures of the Wisconsin crew in the Chicago papers. Ah, I thought, rowing is a good Ivy League sport that he can't expect me to have experienced. "How's Dartmouth's crew?" I asked, causing him to sputter, "Well, uh ... do you have any idea what you'll want to major in?"

In high school, there were two kinds of guys: Those Who Dated Cheerleaders and Those Who Didn't. Those Who Dated Cheerleaders also happened to be Those Who Played Football. Cheerleaders were the girls with tight sweaters and short, short skirts. I wanted one, preferably a brunette. But I did not play sports. So I did not get one.

When I arrived at Dartmouth, I asked around about the crew. No one knew anything about it. So I sailed, played squash, and hit tennis balls for P.E. In the fall of my sophomore year, I bumped into my roommate as he walked out of the crew office. He had just signed up with the lightweights. Not wanting to be outdone, I was, within moments, on my way to becoming an oarsman.

There are many reasons not to row and even more reasons not to row at Dartmouth. In the average season an oarsman will race seven times for a total of about 44 minutes. In preparation for that three quarters of an hour, he will train a total of 900 hours. All sports are demanding, but crew, unlike most, requires that the athlete train throughout the summer as well. Of these 900 hours, 600 will be spent running as many as 12 miles per day, lifting weights, cross-country skiing, and sprinting up and down the bleachers at Memorial Field. During the 300 hours on the water, he will take approximately 252,000 strokes. All this for 44 minutes of competition. Add to this another 300 hours of showering and running to and from the boat house, and one has plenty of reasons not to row.

Each of those 252,000 practice strokes aims to perfect one small set of motions. Lest tedium creep in, Dartmouth adds a few twists. For the last few weeks of the fall term and the first weeks in the spring, snow is a frequent visitor. When it snows, that generally means it is below freezing. And that means something completely different when two-foot waves splash into the boat, something completely different from running windsprints in the fieldhouse. In the spring, during the thaw, the current comes so fast that one can row upstream without going anywhere.

I hope that I've painted a suitably grim picture. Because that, in a sense, is one of the reasons I enjoy rowing at Dartmouth. There .is a raised state of awareness achieved about the ninth mile of a 12-mile run, when the upper body separates from the legs, and there is no pain, only the weird desire to keep running. There is a thrill in pounding out a hundred hard strokes, using up all your energy, and then doing another hundred-stroke drive and having it feel just as strong. There is something about making it 20 times up and down the 50-odd bleacher rows at the stadium. They're all manifestations of the desire and ability to push oneself beyond seemingly rigid physical limits. There attends a feeling of accomplishment, a sense of a stronger, more integral self.

In most pursuits, one has the choice of being a leader or a follower. Crew provides another alternative. The oarsman is not a man alone. If his crew is to succeed, he must in a sense sublimate his individuality; he must become perfectly synchronized with the other men in his boat. Sixteen hands must move away from the body together, just as eight blades must catch the water at precisely the same instant, just as 16 legs must move those blades quickly through the water.

Many sports require teamwork, as do businesses and the like, but almost all leave room for individual superiority, for leaders to emerge to direct the team, for quarterbacks to choose whether to run or pass. Not so with crew. Where one man stands out, the crew is not functioning optimally.

Crew is also an internalized sport. Thousands upon thousands of people cheer the football player. He may not play for the audience, but he has its support. At a regatta, if there are any spectators at all, they will be heard only in the last 30 strokes of the race. The oarsman rows for himself, and his strength comes from within.

Even more important, in football there is an offense and a defense. One advances one's own interests and takes the opportunity to weaken the other team's advances. In crew there is no such opportunity. There is little or nothing that can be done to affect the performance of another boat. The only way to create and maintain a competitive advantage is for the oarsmen to improve themselves.

Sometimes, for 30 or 40 strokes - more if the crew is really good and well-matched - all the men in the boat will move together. Every move the stroke makes will be mirrored by the men behind him, all the catches will hit hard and clean, like a trout going after a fly, and they will all hit at precisely the same instant. When that happens, the boat begins to lift up off the water, air bubbles running under the bow, and there is an exhilaration like nothing else I have ever experienced. For the duration of the drive, everything is effortless, and it is literally like flying.

And I've always liked rowing on the Connecticut, amid the hills and pines, watching the sun reflect off the water as it rises or sets. The coolness of the evening in late spring as we come into the dock, the stars already beginning to appear in the then-stilling waters. It's pretty hard to beat.

Things like that are what I thought about Green Key weekend when we were rowing at Princeton, and they're what I will be thinking about when we go to the championships at Syracuse during finals week. I'm sure it will all seem worthwhile as I take my English exam on the bus.

But 20 years from now as I sit back dreaming of those 30-stroke drives, when everything came together, I won't be surprised if visions of tight sweaters and bobby socks intrude. And then, but only then, I'll probably wish that during the off season I had given football a try.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

June 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

June 1977 By JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

June 1977 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

June 1977 By JOHN FINCH -

Article

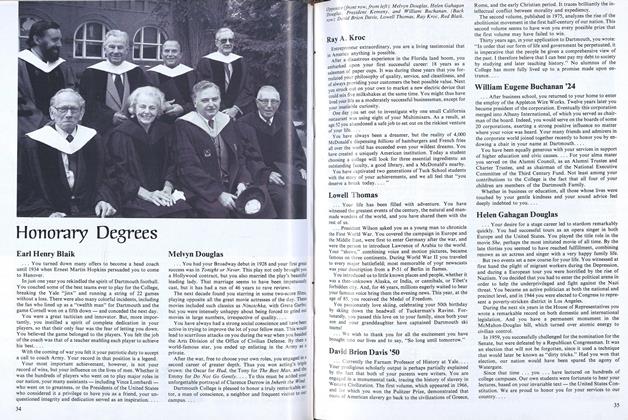

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1977