[The following article is a part of a paper presented before the National Collegiate Athletic Association Conference where Mr. Lillard was asked to discuss his experiences in devising a new athletic system at Andover.]

It is a blind and foolish patriotism which prevents us from acknowledging frankly that -we in America are a long distance behind the English schools and universities in our ideals of sport and that if we ever catch up with them we shall then cease cheating ourselves out of our birthright. Has not England under war pressure just given us an excellent demonstration of the difference between a rooter and a player? The English press spoke out sharply against the forty thousand Manchester rooters who occupied bleachers at a professional soccer game and provided only a corporal's guard of recruits for the army. How different was the response at Oxford and Cambridge. Two-thirds of the Oxford students went at the first summons, and now even the freshmen have put on khaki to play up for their country. The colleges are empty. This is an impressive response —a response by men accustomed to the discipline of athletic contests on the rivers and playing fields. These men are not rooters; they are players, who know how to keep their wits about them under exciting conditions—trained sportsmen, who have learned in many a close match that sheer will power can force a victory after tired muscles have signalled for surrender. English university men are not sitting on the bleachers now; they never learned how to sit on the bleachers at Eton and Magdalen, Rugby and Trinity.

am not going to say that our American students, accustomed as they are to playing the role of organized loafer, would display the inertia of the Manchester soccer fans if given similar conditions. They would not. But it is fair to say that the man who plays the game is making himself a more useful citizen, while the man who sits on the bleachers is developing a bad habit of simply looking on.

And I may add that in one respect the situation of the indifferent Manchester spectator is like that of the American student rooter: he has no opportunity to get into the game. Our American universities, like the English factory owners, cannot afford to provide playing fields, but offer, instead, a seat in the bleachers. It would not be difficult for me to find many of our institutions where a single baseball diamond is offered to hundreds of students. In these same institutions a successful football coach will be retained at almost any sacrifice, but an extra baseball diamond for class games or scrub games is considered a luxury beyond the range of possible financing.

As you know, this is not the' attitude of the English universities. If you vsit in October an English university of three thousand students, you will find acres and acres of fields covered with players who are having a good time. Count the teams if you can and you will find about twenty-five Rugby teams, and the same number of soccer teams, besides field hockey teams, and lacrosse teams. Go to the river and you will discover many oarsmen trying out for the spring races, when there will be a navy of thirty-five eight-oared crews. Everybody is out trying something.

Then return to an American university of the same size and you will find about one hundred picked men playing football, surrounded by a large body of twenty-nine hundred rooters. To make the situation worse, these American athletes are playing in a spot-light of publicity, especially the demi-gods of the varsity. Every one of the twenty-nine hundred fellow-students knows what grade the star quarterback got in his last English quiz. If the right end turns an ankle he is hurried to the infirmary, while the associated press agents proclaim the alarming news to an anxious nation. Perhaps this may seem a bit overstated; but you have seen news of this kind jump from the sporting sheet to headlines on the front page, and from there right into the editorial columns to compete with .other subjects of international importance.

It is needless to proceed further in re-stating these two problems in American sport. We all agree that we must rationalize our intercollegiate athletics and that we must develop intramural sport. Certainly it will require many years to make any great progress, and I can assure you that there is no feeling at Andover that all problems have been solved. In the spring of 1911. it was decided at the Academy that we could make certain improvements in the organization of our sports. There was too much attention being paid to the '"varsity" and too many boys were on the bleachers. A survey of the possible fields for playing space led to the conclusion that there was room for the five hundred boys, although some of the fields were not quite as smooth as billiard tables. The result was a plan to require all of the students to take part in some sport regularly. Whether a novice or not, everyone was to be given a fair amount of instruction in the rudiments of his chosen sport, especially if the game presented technical difficulties which were somewhat forbidding to a beginner. And in planning to have everyone start at the beginning it was thought best to make no exception of the players who had been formerly selfelected members of the "varsity" squad. This meant that a playing season would be divided into two parts, approximately even. During the first part of the season all of the playing would be intramural. At the end of the preliminary season a squad of best players would be chosen to constitute a "varsity," while the class teams would reorganize to play a championship series.

At this point someone may wonder why we did not go the whole distance and organize solely for intramural games. The answer is simple . enough: there is offered in the game with Exeter an opportunity to match strength with an honored opponent in a grappling contest which demands a team's very best skill and strength. This is good for the team and good for the rest of the boys, who welcome a chance to get together and express loyalty. The final game serves as a wholesome climax, which no one at Andover would care to eliminate. So the Exeter game was retained, of course, and to prepare for it there was arranged a short schedule of games with college freshman teams.

When the first experiment with the new plan began, in the fall of 1911, we found that two hundred boys had chosen football, while the other three hundred had scattered, with soccer, track, crosscountry running and tennis, following in order of numbers.

As for the quality of football play produced in this preliminary season, nothing accurate can be said. In the first division, there would be occasional exhibitions of play by the novices which quite startled the coaches, promises of future value which were not always made good. But we had genuine satisfaction in seeing the bleachers empty and the fields covered with boys who were having a mighty good time. And when the "varsity" squad was chosen the coaches felt that the extra amount of time which each player had actually put in under fire would just about make up for the time lost in getting the team under way. That is to say that the new plan as compared with the old had given each individual four times as much actual playing in games, but of course not the same kind of experience that comes with meeting an unknown opponent.

At the end of that first season under the new plan we were pleased to see our first team win from Exeter. It proved to some of our anxious young alumni that the plan would not ruin a team. On the other hand, no one believed that the team had won because of the new plan, "for five of the eighteen men who played had been trained under the old plan as well as the new; and I may add hat one of the five was the All-America fullback for this year, Captain-elect Mahan of Harvard. He was a great power on offense, though, I believe, on defense he. played last man and had only one opportunity to tackle.

Perhaps you may be interested in the question of whether or not a team playing under our plan can cope successfully with one which plays under the old plan with outside coaching. It is certainly not our major issue, but at the same time we confess to honing1 for a fair measure of success in the Ion? run: and I shall be glad to sketch briefly the history of our experience in the three years which have followed our first experience in football. I stick to football simply because I have been closely related to it. The baseball story would run pretty nearly parallel.

Of the four seasons of football in which our plan has been in operation the second season was bv far the fairest test of its effect upon the school team. In this season 1912 there were no left-over players who had won their spurs under the old plan. The material was about average in weight and power When they went on the field to play Exeter they were opposed by an average Exeter team of about equal power. The result was a very evenly-contested match, which might have gone either way. Because it happened to go Andover sway by one touchdown, there was no feeling that the victory was due to the new plan. But there was some assurance in the minds of the faculty-coaches, and others who followed the season closely, that under normal conditions the new plan would not seriously handicap the development of a school team.

In justice to our plan let me say that the last two seasons have brought unusual conditions into the final game with Exeter. We have been defeated twice by large scores; we. would have been defeated twice by large scores under any system ever devised. In 1913 there came the first reaction at Exeter after a long series of defeats. The result was an exceptionally powerful team. At the same time our material dropped almost to the zero point; so that the best team we could develop was far below the Andover standard. Naturally this team was outclassed in the annual game.

There was a still greater surprise waiting- for us in 1914. Exeter's season record had been unusually strong, with not a single touchdown registered against it. But our own team was ever so much better than the weak product of 1913—it had shown some promise of strength against the Yale freshmen, and .was almost an average Andover team. Nevertheless, all of the strength which our boys could summon availed not at all when that powerful Exeter team got under way. There was material which would make any college coach in the country very ill from envy. If published weights can be trusted the Exeter average was exactly equal to Harvard's .and five pounds heavier than Dartmouth's. Our team was again outclassed, and had only a small crumb of comfort in the fact that they were the only team to cross Exeter's goal line. May I repeat that if we had been given the same defenders trained under the old plan, and the same opponents, the result would still have been a one-sided game.

This report on our experience is necessarily limited. Although we do no feel that our plan is a perfect one, nor that our experience is necessarily illuminating to other institutions, we do believe that we have made genuine progress in meeting our own problems. And as for the future, we shall certainly continue to follow up a policy which has brought so much benefit to our boys, physically and morally. W believe that a resident in one of our American educational institutions should not be allowed to choose between scholarship and athletics when he can just as -well have both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER

March 1915 By Kan-Ichi Asakawa '99 -

Article

ArticleThe message of the College does not come to all with the same distinctness

March 1915 -

Article

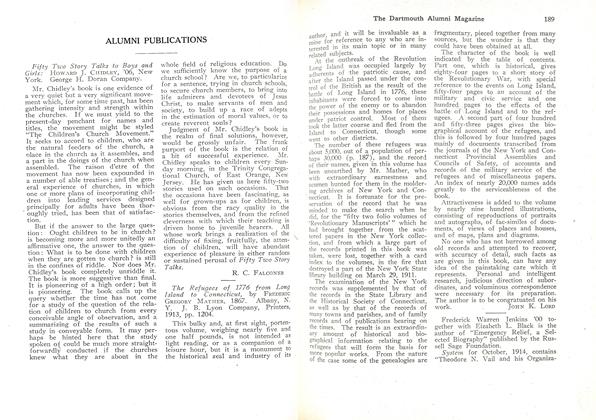

ArticleALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March 1915 -

Class Notes

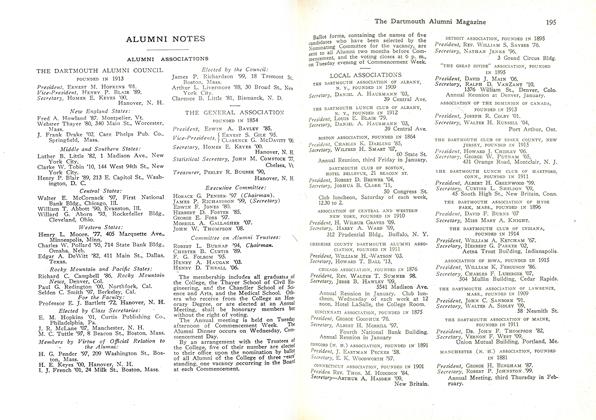

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1915 -

Article

ArticleTWO MEN OF DARTMOUTH

March 1915 By William Byron Forbush '88 -

Class Notes

Class NotesST. LOUIS ASSOCIATION

March 1915 By LEIGH C. TURNER '04