period of ups and downs, the Dartmouth football season ended, not inappropriately, in a mud puddle. When it was all over, nearly everybody heaved a sigh of relief; not that disaster had been expected or even vaguely feared, but that a disagreeable experience of some weeks' duration had come to a conclusion. Why a Dartmouth football season should be thus characterized, however, is not easy to determine. Doubtless the condition is purely psychological. Perhaps Dartmouth folk of an earlier day experience a touch of loneliness as they look over present schedules, which in so far as New England relationships are concerned, display a degree of splendid isolation that is rather disconcerting to those who recall more neighborly times. The old, familiar names are gone; a new tribe of coming giants has taken the places of erstwhile rivals, and has as successfully disputed our claims to prowess.

Several times we have come near enough to a trouncing to satisfy our desire for a genuine contest; yet we are not pleased. We were beaten by Princeton, and tried to content ourselves with the newspaper dictum that our was the better team. We beat Syracuse, and derived what satisfaction we could from the fact, without regard to the accompanying fact that Syracuse probably had the better team. Pennsylvania and West Virginia both showed greater determination and versatility with the odds against them than Dartmouth could muster. No one has been particularly impressed with our skill or our tenacity. We are not so bad as we might be; nor so good as we might wish. We have, in short, become common-place,—the saddest .condition imagina- ble. There is thrill in sniffing the air of the heights; there is hope of rebound if bottom is struck hard enough. But from the dead center of the common-place, motion in any direction is difficult to achieve.

Reasons for this are more easily cited than proved. That any person or persons may be blamed is far from likely. That the present system has become threadbare seems not improbable. Such is the history of football systems. They work adequately for a time, and then inevitably pass. Some last longer than others; usually where they are the outgrowth of a highly developed organization, whose changes are more perceptible within than without.

And, at all points, interest must needs lag on account of the schedule. From the view of the higher sportsmanship it is, doubtless, the fair thing for a college team to welcome all such honest competitors as present themselves from whatever quarter, and to take on those who assure the most gruelling test of mettle. The process of whetting one's teeth on the bones of carefully selected little fellows byway of preparation for some final titanic test has about it something of the revolting. But, if real interest is to be maintained in sport or in war, it is needful to know more of an antagonist than that to worst him will demand severe effort. Rivalry, like love, may have no better excuse than propinquity, though its essential foundation is more often found in known similarity of general social status.

Thus Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are bound in a football triumvirate more by a traditional social tie than by any athletic one. It was a similar tie that held Dartmouth to Amherst and Williams long after the college football teams had ceased to be well balanced athletic opponents. The social similarity still holds, and, under slightly alteredy conditions, is more than likely to result in resumption of football relations—simply in the nature of things.

In location, type of constituency, and character of undergraduate life, Amherst and Williams are more similar to Dartmouth than is Brown. The lack of such evident similarity constitutes one explanation of the slowness with which Brown and Dartmouth approach the resumption of football relations long after the burial of the athletic hatchet. Yet the two colleges have a great deal in common, enough to make their coming together on the gridiron only a matter of time. THE MAGAZINE will be glad to welcome the event. Nevertheless it would question the advisability of making the meeting the season's final for either team. To do so would be to lend an artificial ardor to the reconciliation that in itself might jeopardize the development of those genuine and kindly intimacies out of which the best athletic rivalries grow.

But these are not practical considerations. A final game between Brown and Dartmouth on a neutral field would bring tall letters into the newspaper headlines, induce columns of prognostication, and stimulate an exodus from Providence and Hanover that would leave those two towns looking like ancient capitals of Nebuchadnezzar. If that is the case, what contrary argument of supposition is likely to count? The death of Miss Sarah Smith, at her Hanover home, will touch a good many generations of Dartmouth men. From the old Dartmouth of the days of her father, President Asa Dodge Smith, to the new Dartmouth of the present, she was an important figure in the life of the community. To whatever was due her as daughter of a former President of the College, she added by virtue of a very unusual personality. Energetic, kind, sympathetic, hospitable, she made in her home, twenty years ago, a family table for a select few of students. These men she governed with a gentle, but unyielding rule. And through them she exercised no small influence upon the entire college. Her word was law in the conduct of social events : no party was complete where she was not listed as a patroness. Her hold, too, upon individuals was strong, and her control salutary. Her motherly interference at the right time—which she was always wise in choosing—helped to keep many a youngster in the path of diligence and good behavior.

Of late years, ill health had compelled her retirement from wonted activities. Part of the time she spent in Hanover; part, in New York. But her interest in the life of the College remained unimpaired, and her home continued unbrokenly a place of alumni pilgrimage.

One of the best Dartmouth events of recent years was the reunion of classes held at the Merrimac Valley Country Club, near Lawrence, Mass., at the time of the Georgetown football game. The classes called together were '97, '98, '99, 1900 and 1901, the group that had been, as students, in the midst of the fundamental transformations in the College. All were well represented, and those who attended experienced something very much better than a good time. In addition to the pleasure of renewing old fellowships, there was, it seems, clearly evident that serious interest in the right usefulness of the College that is increasingly characteristic of Dartmouth alumni gatherings.

The affair was handled with a tact and skill that in themselves were guarantees of success. It may, therefore, well be hoped that the same ability will be directed to a repetition of the event: or, if not, that the example will be imitated by other classes. It is becoming customary for various colleges to have a sort of old home day at other times than Commencement. Some kind of prearranged friendly invasion of Hanover from time to time might perhaps be scheduled. The groups at no time need be large. Alumni sometimes complain because they have no adequate opportunity to come with their wives to Hanover and, see the College in operation. After all, the opportunity is theirs for the making. Why not, during the winter, week-end visitations of groups of twenty to thirty couples at a time. The Inn could well take care of them at that time and there would be no great difficulty in arranging special entertainment of one kind and another. To the energetic ones in reasonably nearby alumni associations the idea is recommended for serious consideration.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsVARSITY FOOTBALL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1916 By Slurgis Pishon -

Article

ArticleFRANCIS BROWN

December 1916 By John King Lord '68 -

Article

ArticleAT PLATTSBURG

December 1916 By Morton C. Tuttle '97 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1916 By Conrad E. Snow

Article

-

Article

ArticlePETITION CIRCULATED FOR BUILDING REGULATIONS

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticleFeted as Former Coach

March 1949 -

Article

ArticleThe Art and Artists of Maine

DECEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

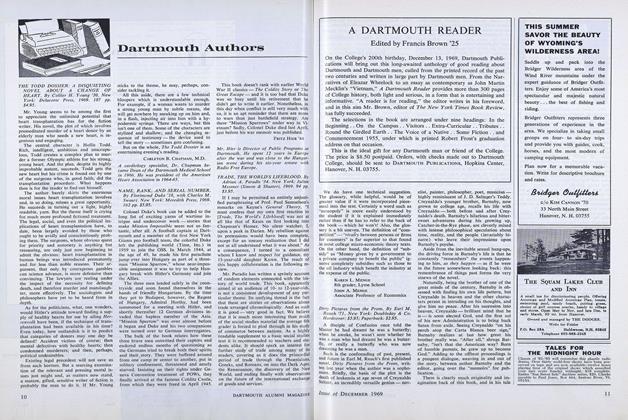

ArticleA DARTMOUTH READER

DECEMBER 1969 By Francis Brown '25 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATION OF CHICAGO

March, 1924 By Warren D. Bruner