The death of Francis Brown, which occurred on the 15th of October last, removed from the circle of the alumni of the College one who was in many repects its foremost representative.

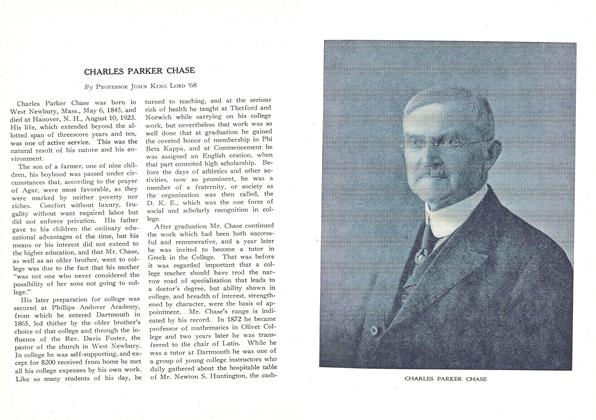

Dr. Brown's relation to the College was historic and inherited. His grandfather, whose name he bore, was the president of the College .during the troubled years from 1815 to 1820, and to his wisdom, sacrifice and devotion were due, in great measure, the security of the charter and the existence of the College. His father, Samuel Gilman Brown, was a graduate of Dartmouth and a professor from 1841 to 1867, then president of Hamilton College, and in his later life again an interim instructor at Dartmouth, filling a vacancy in the department of intellectual philosophy.

Dr. Brown was himself a graduate of the College in the class of 1870, being the foremost scholar of the class, and a tutor in Greek for two years, and in 1879, on the death of Professor Proctor, he was invited to the chair of Greek. Later, he was a member of the College board of preachers for the eight years of its existence, and from 1905, until his death, he was a member of the Board of Trust. Twice he was offered the presidency of the College, but felt that the call of duty lay in another direction.

Following in the steps of his father and his grandfather, he turned in his youth to the Christian ministry, and graduating at Union Theological Seminary in 1877 he received the Seminary fellowship, by which he enjoyed a two years' residence at the university of Berlin. On his return from Berlin he was recalled to the Seminary as an instructor, and the connection thus made was ended only by his death, becoming more intimate and vital as he became successively professor, a director and president of the Seminary. His wide scholarly interests were indicated by his

active membership in several learned societies, by his association with the directorate of several important institutions and by the honorary degrees conferred upon him by many colleges and universities in this country and by the universities of Glasgow and Oxford in Great Britain. The fruit of his studies appeared not only in his utterances in the pulpit, but in various publications, some that were tributary to current discussion, and some, like his Hebrew andEngish Lexicon of the Old Testament, that were a permanent contribution to linguistic scholarship. As a scholar he held the first rank among the living graduates of the College.

The period of his connection with the Seminary was marked by that upheaval in religious thought that attended the rise of the so-called "higher criticism," by a changed emphasis in belief and, in some cases, by a re-statement of doctrine. In this movement Dr. Brown had a part as a leader and not as a fanatic. He retained the strength and simplicity of his early faith, but enlarged and enriched it by wider knowledge and more generous sympathy. His leadership in the movement to interpret religious truth according to the results of modern scholarship and modern thinking, and to bring the Seminary into accord with the advance of knowledge, did not escape criticism and opposition.

When the Seminary was under fire before the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church for unsoundness of doctrinal instruction, as indicated by the examination of some of its graduates, Dr. Brown upheld its liberty and defended its teachings so successfully that the institution was more firmly established in the confidence of, the religious world, and, in the years that followed, it received a more generous support in the number of its students and in material endowments.

It was in such activities and relations as these that the characteristics of Dr. Brown appeared. He was a scholar by inheritance and by training, loving knowledge for knowledge's sake and also for its application to life. His ideal was of the highest. From his college life to his latest study he was satisfied with nothing less than his best, and to make his work complete he was willing to give to it unlimited time and labor. His ideal was matched and strengthened by a sense of duty. It was this sense that led him to decline the presidency of the College, as he would not abandon the Seminary to which he felt himself in honor bound.

To his scholarship, developed as much on the side of power as of knowledge, he added administrative ability of a high order, which was recognized by his associates in placing him at the head of the Seminary, and was attested by his success in that position. In the conflict of opinions and the consequent tendency to draw apart of men who ought to have worked together, Dr. Brown was chosen for this position because of the sagacity by which he was able to estimate opposing interests and to bring them into working relations. Never a settled pastor, he was greatly sought as a preacher, being effective in the pulpit not so much from the grace and force of his delivery as from the depth and scope of his thought, the richness of his spiritual experience, and the almost matchless simplicity and beauty of his style. His English was a draught from a "well undefiled." His prayers were the expression of a spiritual life that carried to others the suggestion of its divine source and led them to desire a knowledge of it.

Personally Dr. Brown was a noteworthy man. Of fine physique, tall and well proportioned, his body was a fitting symbol of his mind. In his youth he engaged in athletic sports and never lost his interest in them, being ever an interested spectator of the contests of college teams. In manner Dr. Brown was cordial but reserved. He had no fund of small talk, and did not always appear at ease in ordinary conversation; he did not have the art of communicating himself. With very few could he be said to be intimate. He did not easily reveal himself in intercourse, as it was less difficult for him to disclose his feelings with his pen than with his voice, but he had a deeply sympathetic nature and under a quiet exterior carried a heart that was warm and unusually affectionate, and that had an intense and often unsuspected interest in others. Of the fine quality of his family life this is not the place to speak.

The death of Dr. Brown is a severe loss to the College, as it not only removes one of the prominent members of the Board of Trust, but one who for some time has been the only representative on that Board of the clergy, who once had so large a proportion, and the one who, apart from the president, has been most closely in touch with educational movements. His experience, sagacity, and devotion to the interests of the College cannot be replaced, but to his successor he has left an inspiring example.

Dr. Brown's last visit to the College was at the inauguration of President Hopkins, when, on behalf of the Trustees, he put into the hands of the new president the charter of the College as the symbol of its interests. No one who saw him on that occasion failed to note the face on which disease, that was all too soon to become fatal, had set its mark, and to feel that it was only by a heroic effort that he delivered a message that was in the nature of an accolade, as he said of the charter and to the president: "It is good law, and good history, and good religion. It has been through the fire. Guard is as your life."

He himself has fulfilled that trust, he has kept his faith, and now he has entered into his labors and his works do follow him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsVARSITY FOOTBALL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1916 By Slurgis Pishon -

Article

ArticleAfter a highly uncertain and unsatisfactory

December 1916 -

Article

ArticleAT PLATTSBURG

December 1916 By Morton C. Tuttle '97 -

Article

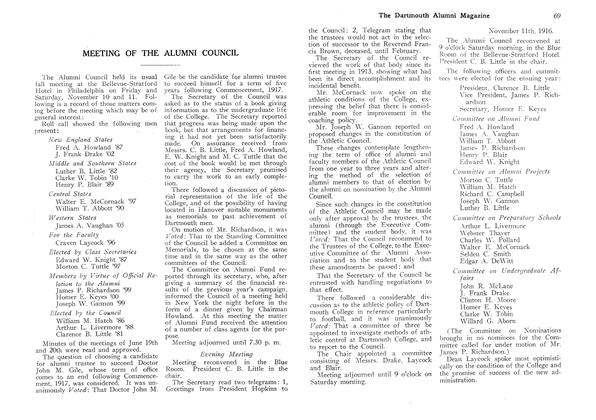

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

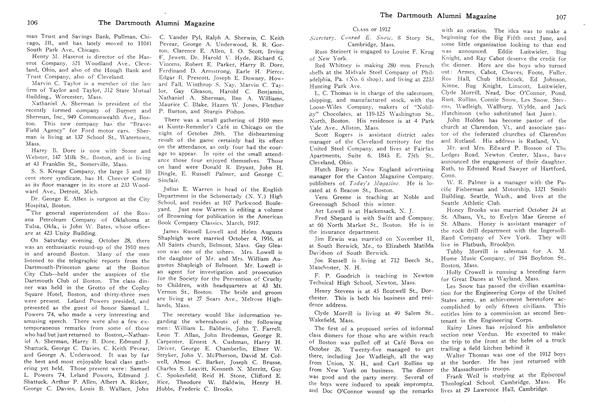

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1916 By Conrad E. Snow