Richard Harding Davis said that the staging of the maneuvers for the Plattsburg training regiments gave appearance surprisingly similar to real actions of like size. So few would care to make the necessary examination to check this that the statement will stand. I suspect the two things are about as similar as this noon's lunch is to meal time or an Arctic expedition. The wishful tone in which our officers stated that we'd keep down flat all right if the other side were only firing bullets made me think we were not real actors, and the almost plaintive way our superior's voice hung on "only" made me feel that he had no great hope of anything but death teaching us much. I am sure he would have enjoyed the working out of the problem with courage and the luck of sudden death added as variables to a problem which weighs judgment and patience and resource and endurance and foresight and power of co-operation against the same desirable traits in one's opponents,—truly a game whose elements a true man must love. If you know the best type of officer of our service you'd know he would love these things and understanding them, he would become their living product.

Analyze the qualities that a soldier must have, realize that an officer must be able to make others understand him, offer a chance to see the application of such qualities even in a superficial way, and you will readily understand why the Plattsburg idea stands so close to the heart of these who have understood it. Honor and courage and foresight and patience and endurance, combined with youth and health, are wonderful companions for a month a year.

I remember well a picture I ran onto one night, — the light of a camp fire showing on the full front face of an officer and the profile of every man who could get near him. He was leaning a little forward and I think he didn't see the fire he was looking into. Obviously he had been talking to a few men and others had gathered to hear. He had not wanted this, for his voice was so low I only got a little,—"the sergeant ran onto them and could have gotten away, only he tried to signal us and they got him, and he crawled far enough even then so we saw him." I'm sorry I didn't know that sergeant, I'm sorry I didn't get acquainted with that quiet voiced officer toward whom the sergeant crawled. That's one of the aggravating things about our instruction camps, there are so many men that you want to know. The whole thing grips you so hard that it lays its own tie on you, and other ties are loosened as ties do loosen under the hard hold of a new strong one. You hear very little about college or city or local ties and much of those of squad and company and regiment, so it's hard to write of Dartmouth at Plattsburg, or Yale, or California, or the wealthy or the poor at Plattsburg, for one of the sure things is that a training camp is the finest kind of obliterater of all lines which can even faintly segregate society into groups,—that's one reason we are for universal military training. Once we are all in uniform we begin to get acquainted and begin to do the same things so we can rate real ability free from the chance of personal advantage. It seems to us as though it would be a good thing for / all the boys, rich and poor, much or little educated, to be dressed alike and treated alike for a year of their lives. We think they'd like one another fine and that they'd talk things over and understand one another, and perhaps because they liked each other that later on when one hired and the other worked they would still talk things over and understand better than we do. Anyway, if they wanted to fight they'd fight with the full belief that if the government wanted them to stop it had power enough to make its order good, and they'd be used to listening to a command.

I have not been able to get figures as to the number of Dartmouth men who have been at the training camps. Williams beat us not only on percentage of men attending but on actual numbers. Harvard was leader, then Yale, with large numbers from Princeton and Cornell. It seemed to me the technical schools had a small representation. I have said that ordinary lines were largely obliterated. In your company you eventually learned a good deal about many of the men and in this information usually from what college they came.

The only exclusively Dartmouth affair I have attended occurred last year. Notices were posted that a Dartmouth picture was to be taken,—to use European parlance, at a certain place at an agreed time. I think- ten men gathered before that camera and the photographer gave us orders as to grouping ourselves. We didn't mind that for we had been getting orders from most anybody who wanted to give orders. So we grouped and he made the exposure. Then he issued more orders and as the correspondents say, kaleidoscopic movement brought another group, which he also took, and we scattered, feeling that if the college insisted on a picture we could offer a selection. There is no group of Dartmouth men trying to look like soldiers. That picture is rarer than the Mona Lisa. Our soldierly figures will never show in picture, because as the photographer later explained, "There wan't no plates in the holder." I am sorry, because I like to read articles illustrated with group pictures, under which are notes stating that the author is third from the left with his foot on the lion's head. In thinking of the matter again, I believe that any loss by lack of this picture has compensations.

You saw men you knew in the evening and sometimes at general lectures, where all men in camp came to hear General Wood talk. They told you of others who were in camp, but mostly you lived with your company and were too busy to do much visiting. Reveille at 5.45, setting up exercise 6.00, breakfast 6.30, morning drill 7.30-11.30, dinner and drill or lecture, 2.00-4.00, retreat at 5.30, supper at 6.00 and commonly a lecture at 7.00, didn't offer opportunity for calling. All this out doors and mostly on the move and then sleep out doors.

Mostly you went to bed early. You'd grow more sleepy and half notice the light and half hear the singing and sort of wish you were going to be awake to hear the bugles sing taps each for its own regiment, for that is beautiful, but mostly you didn't hear that. The next you hear is first call and it's tomorrow. Yes, you should go to Plattsburg.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsVARSITY FOOTBALL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1916 By Slurgis Pishon -

Article

ArticleAfter a highly uncertain and unsatisfactory

December 1916 -

Article

ArticleFRANCIS BROWN

December 1916 By John King Lord '68 -

Article

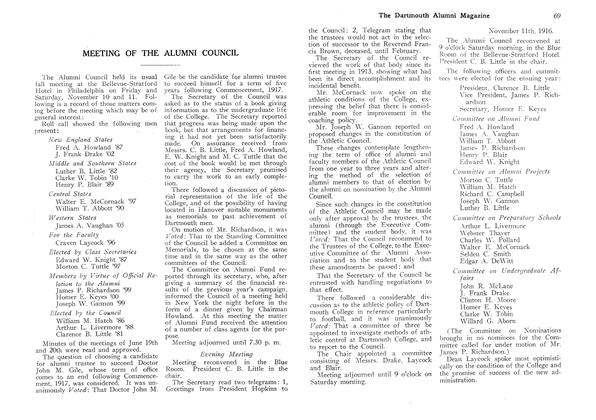

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1916 -

Class Notes

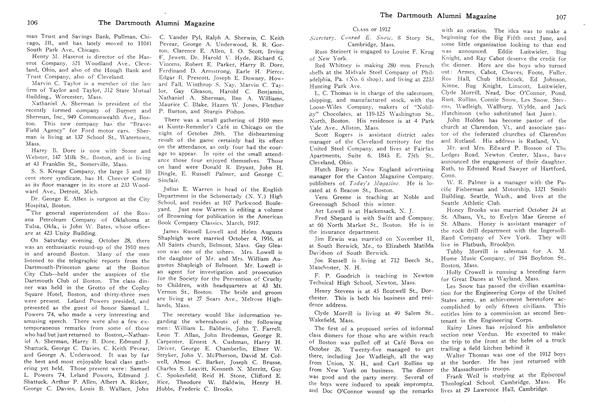

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1916 By Conrad E. Snow