year to encounter more perplexing difficulties than those which have beset the path of President Hopkins. But he has met them as one who rejoices in a trial of strength.

First adjustments to an environment, new yet perfectly familiar, were made easily, - almost as a matter of course. Various avenues for faculty investigation with a view to improvement in the educational effectiveness of the College were promptly planned. Close and sympathetic contact with the student body was established. Trustees and faculty were brought into fresh and cordial fellowship of coöperation. The alumni were visited and frankly informed of the responsibilities and aims of the College. Their response was instant and hearty. All the forces of the College were thus well in process of alignment for the joint fulfilment of their task when the certainty of war became apparent.

In the necessity for taking a well defined position President Hopkins displayed no hesitancy. Every agency at his command he employed in arousing the College community to the patriotic need of the hour. To his personal influence more than to any other one cause is, without doubt, to be attributed Dartmouth's astounding outpouring of men for service; — not that he urged anyone's going but that he had created an atmosphere of patriotism.

For those who remained at the College he brought means to, privide military training. In the face of steadily depleted undergraduate numbers, he found the trustees unanimously ready to support him in a policy of maintaining the College organization unimpaired even at staggering cost. Hence, while many another institution was still puzzling as to measures of drastic retrenchment, Dartmouth's message of vigorous confidence was published. And, lastly, a Commencement which it had been proposed to abandon, was rescued to become one of the most notable occasions in the history of the College. Thus a year of tribulation has come near to being a year of triumph.

Again a Dartmouth man has yielded his life in the great cause. Paul G. Osborn of the Class of 1917 entered the American ambulance service with the Dartmouth unit that sailed for France early in May of this year. At the dinner given in honor of the unit by alumni in New York, he was spokesman for the volunteer group. On the third day of active service at the front, while driving his ambulance, he was terribly injured by a shell explosion. The amputation of both legs became necessary. Death soon followed. Paul Osborn was buried with military honors. Upon his coffin, before it was lowered into the grave, was placed the Cross of War.

This Dartmouth man descended into the thunderous depths of battle to bring hope to others. He found there for himself quick agony and untimely death. This war's chronology of Dartmouth's sacrifice, wherein his name stands third, has, in the inevitableness of things, just begun to unfold. 'Other names fate will add, of men as young as he, as full of ambition for themselves and of promise in the eyes of family and friends. For these last it is always that great promise of youth, thwarted by the pitiless veto of war, that abides as a never ending source of grief; unless they may find consolation in such philosophy as that of Osborn's father who in a letter writes this brave sentence: "It is hard to do so, but we try to think that our boy has done more by his death in this noble endeavor than he could do in any other way."

Here finds compact expression the thought, old as human heroism, that the completeness of life lies not in its duration but in its accomplishment. Two years since there was privately printed in England, "in memory of friends who had died fighting for their country," a pamphlet of selections from an eighteenth century translation of Plutarch's Mor alia, which conveys the same idea with convincing beauty. The extending company of those that mourn has increased the demand for this pamphlet until it has passed into many editions.

It is not long. The publishing of it here and now, as the shadow lengthens across the road that so many of America's best must travel, seems appropriate. It is entitled

PLUTARCH TO APOLLONIUS : CONSOLATION ON THE DEATH OF HIS SON.

Now if Death be like unto a far journey, yet even so there is no evil at all therein, but rather good; for to be in servitude no longer is a great blessedness, and felicitie. As Plato saith, 'We ought to be delivered from this bodie and by the eyes only of the mind contemplate and view things as they be; then shall we have that which we desire; then shall we attaine to that which we love, wisdom, even when we are dead and not so long as we remain alive, and then we shall converse with pure intelligences, seeing evidently of ourselves all that which is sincere, to wit Truth itself.' We read that many men in recompense of their devotion have received death as a singular gift, a favour. In sum, every man ought both in meditation and in earnest discourse with others, to hold this for certain; that the longest life is not best, but rather the most virtuous.

Little difference you shall find between short time and long, in comparison of eternitie, for that a thousand years and ten thousand years are no more than the smallest indivisible portion in respect of that which is infinite.

This hastie and overspeedie death different nothing from others: for like as in the return to our common native country, some march before, others follow after, and all at length meet at one and the same place; even so in travelling this journey of fatal destiny, those that arrive late thither gain no more advantage than those that have hither come betime. I would rather say that innocency is the greatest and most sovereign medicine to take away the sense of all douleur; moreover the love that we bear unto one that is departed consisteth not in afflicting ourselves, but in doing good unto him so beloved of us. Now the profit and pleasure that we are able to perform for them who are gone out of this world is the honour that we give unto them by celebrating their good memorials. For no good man deserveth to be mourned, but rather to be celebrated with praise. He is not worthy of sorrow but of an honourable and glorious remembrance. He requireth not tears who doth partake a more divine and heavenly condition of life, as being delivered from the infinite care, perplexities and calamities which they must needs endure who abide in this mortal life, until such time as they have run their race. And Aristotle saith, in his book entitled 'Eudemus' or 'The Soul'We esteeme the dead to be blessed and happy, as being new translated into a far better and more excellent condition than before: which opinion is so ancient that no man knoweth either the time when it first began, or the first author thereof; but from all eternitie this custome been among us.'

Semblably Xenophon, being advertised by certain messengers returned from the battle that his son was slain, put off the garland which was upon his head and demanded of them the manner of his death; and when they, related unto him that he bore himself valiantly, and manfully lost life; he, after a little while, set the coronet of flowers again upon his head, saying unto them that had brought these tidings: 'I never prayed that my son should be long lived, for who knoweth whether this might be expedient or no? But this rather was my prayer, that they would vouchsafe him the grace to be a good man, and to love and serve his country well, the which is now come to pass accordingly.'

Young men of excellent virtue who die in their youth are in the grace and favour of the gods, for being taken in their best time, giving testimony of the truth of this wise sentence of Menander:

To whom the gods vouchsafe their love and grace, He lives not long but soon hath run his race.

But peradventure my most loving and right dear friend, you may reply that young Apollonius your son enjoyed the world at will, and had all things to his heart's desire. True it is, I confess. But in regard of him who is now in a blessed estate, it was not natural to him to remain in this life longer, and so much the happier he is. Certes, this son of yours is gone in the very best of his .years and flower of his age, a young man in all points entire and perfect, esteemed and well-reputed of all those who kept him companie, loving to his father, kinde to his mother, affectionate to his kinsfolke and friends, studious of good literature; and to say all in a word, a lover of all men, respecting those friends who were older than himself, making much of his equals, honouring those who were his teachers, to strangers most civil and courteous, gracious and pleasant to all; generally beloved, as well for his sweet attractive countenance, as his lovely affability.

All this I confesses most true. And you ought to consider, that he is translated before us in very good time out of this mortall and transition life into everlasting eternity, carrying with him the general praise and blessed acclamation of all men; and if the saying of ancient poets be true, as it seemeth verily to be, that good men have honour in the other world, and a place allotted them where their souls abide and converse,' surely you are greatly to hope very well that your son is canonized and placed in the number of those blessed saints.

Plutarch, Moralia 107 — 120. Selected passages from Philemon Holland's translation (1603), pp. 517 — 30.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

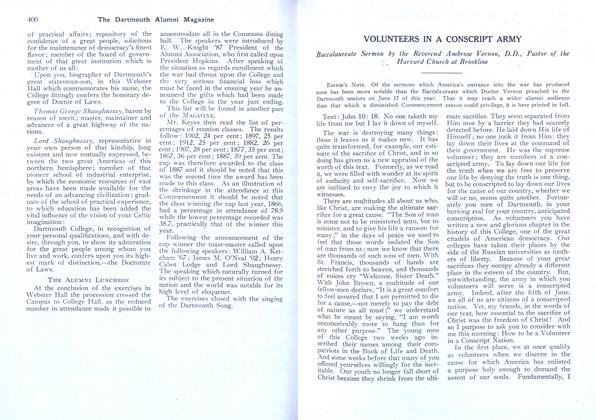

ArticleVOLUNTEERS IN A CONSCRIPT ARMY

August 1917 -

Article

ArticleGIFTS TO THE COLLEGE DURING THE PAST YEAR

August 1917 -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETINGS OF THE TRUSTEES

August 1917 By Henry Hoyt Hilton." -

Article

ArticleWEDNESDAY

August 1917 -

Article

ArticleMONDAY

August 1917 -

Article

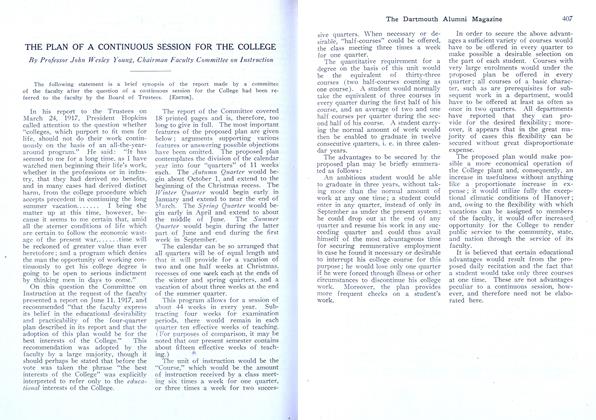

ArticleTHE PLAN OF A CONTINUOUS SESSION FOR THE COLLEGE

August 1917 By John Wesley Young