"The Essential Mysticism," by Stanwood Cobb '03, has been published by the Four Seas Co., Boston.

"Sketch of the Aero Club of New England, 1902-1918," by William Carroll Hill '02, has just been published in pamphlet form.

The music written by Hugh A. Mackinnon '14 for Milton's Christmas anthem, "This is the Month," has recently been published.

A new and cheaper edition of "Guide Book to Childhood," by William Byron Forbush '88, has been issued by the George W. Jacobs Co.

"Infantile Paralysis in Vermont, 1916-1917," by the late Charles C. Caverly '78 appears in the September number of the Bulletin of the Vermont State Board of Health.

Shirley Harvey '16 is the author of a poem, "Rainy Days," in the November issue of Poetry.

"Prussianism in Poland," by Charles Downer Hazen '89, appears in the World's Work for November.

John Barrett '89 is the author of "What the World Has Done to the Monroe Doctrine," in the issue of Current Opinion for November.

"The Kaiser's Secret Negotiations with the Tsar, 1904-1905," by former Professor S. B. Fay appears in the American HistoricalReview for October, 1918.

A College Man in Khaki; Letters of anAmerican in the British Artillery. BY WAINWRIGHT MERRILL, Ex-'19. Edited with an introduction by Charles Miner Stearns. George H. Doran Company, New York. 234 pp.

Wainwright Merrill, Dartmouth '19, was killed November 6, 1917, when an enemy shell struck and wrecked the building in which he was billeted in Ypres. His letters to the late Charles M. Stearns, formerly instructor in Dartmouth College, supplemented by letters to his relatives and friends make up the book, unified by a running comment by the editor. Mr. Stearns, who arranged the letters and supplied the prefatory note, died from an attack of influenza on September 27, 1918, a few days before the official publication of this book.

The average American college student has a tender love for England. Its splendid traditions and noble history have a charm which no other land seems to have. Wainwright Merrill articulated this. Because he could not wait for the United States to declare war, he enlisted under an assumed name in the Canadian Field Artillery in the autumn of 1916. This deep sympathy for England and for the English tradition breathes through all of his letters. "It is a great thing for the Native-Born (American)" he says, "to see the Homeland; this England he has always read of, dreamed of, and desired for his own. That desire is bred in one as part of his make-up—stronger than friends or blood-tie, stronger than the man himself."

Merrill's point of view in matters literary and social is particularly interesting. Although he was only nineteen years of age when he was killed, he had a very definite outlook upon life—the combined product of his student days at Dartmouth and at Harvard. His philosophy of life is partially disclosed in flashes of opinion which are called forth by the various experiences through which he has passed. Military life with its new duties and slang, glimpses of English shires and public schools, rambles about Oxford town, in and out of the colleges, fragmentary and disjunctive judgments on passing events and people, combine to make his letters of special interest not only to the general reading public, but to Dartmouth men in particular. Dartmouth places and people are frequently mentioned.

The letters show that Merrill had the true English feeling for aristocracy. It is left to the youth of this generation to work out the balance or resistance between the old-fashioned idea of aristocracy and the new—especially in the sense of how the new idea of aristocracy functions in a democracy. This, after all, will be one of the problems to be solved in connection with the leveling philosophy of Bolshevism. Merrill was impatient with the leveling-down tendency which destroys the vital life-giving forces generated in the search for the best. "Democracy," he says, "as a theory is all very well, but until we reach a Utopia of educated sober-lived lower classes, I cannot (for one) believe in it in entirety, or even in a large measure. Not yet. I hold to a class system of ability and ideals. If a man of low origin shows sterling qualities, well and good, but if he is rotten and narrow visioned and prejudiced towards the great things of life, I cannot meet him as equal and brother." He follows up this judgment with a remark which goes to the very pith of the problem, "Education, though, is the possible salvation for democracy."

Merrill has an incisive way of jotting down his thoughts in a clean-cut, brisk manner. One gets the impression, so rare in similar collections, that these letters were not written with an eye on possible publication. As a result, the comments on life and manners and letters are refreshingly naive and pointed. His literary criticisms throw light on his soundness of taste. He quotes Chaucer, tells of his enjoyment of ''Pendennis," and gives way to a sound drubbing of Galsworthy for the latter's "Beyond." But Kipling is very near his heart. This seems to have been one of the permanent contributions which Dartmouth made upon him. But Kipling was one of the authors read aloud by Mr. Stearns to his groups of student friends. Merrill pays tribute to the Dartmouth instructor in his first letter. ". . . . much thanks to you for showing me many things in literature that I did not know, and my debt to you as regards Kipling, which is indeed great." In contrast with this warm appreciation for Kipling is the comment on Galsworthy: ". . . . this Galsworthy is jolly-well rottener."

But Dartmouth men will read these letters of a Dartmouth hero. They will take a special pride in him, as in so many of her war dead. In the very last letter of the book is this printed sentence, "I say, Dartmouth does put a sort of brand upon a man, does it not?" She does. The personality which is revealed in this volume of war letters proves it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ROLL OF HONOR

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleMILITARY NEWS

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleFirst Dartmouth Governor of New Hampshire in more than thirty years John H.

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleTHE CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION IN WAR TIME

December 1918 By Ralph J. Richardson '09 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1918 -

Class Notes

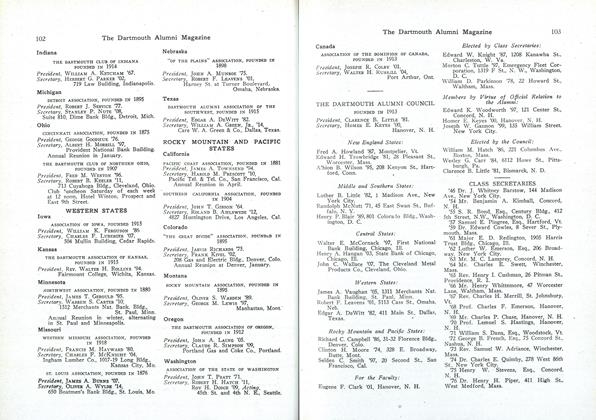

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

December 1918

Books

-

Books

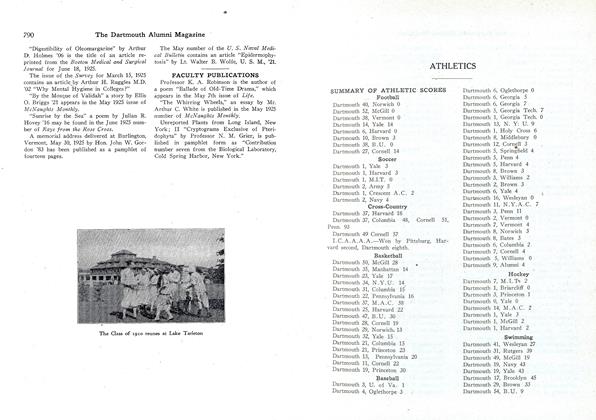

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

August, 1925 -

Books

BooksPROBLEMS IN INCOME TAX FUNDAMENTALS.

October 1937 By C. W. Sargent '15 -

Books

BooksFore

DEC. 1977 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Books

BooksFRATERNITY VILLAGE,

October 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE SIX LOVES OF "SHAKE-SPEARE."

OCTOBER 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksBLACK ANGELS OF ATHOS

January 1935 By John Barker Stearns