It may seem odd that a Harvard Ph.D. in philosophy, Pennington Haile '24, well known for his robustness in mountain climbing and skills in European languages, and Alexander Laing '25, a maritime scholar, novelist, and Dartmouth Professor of Belles Lettres who has spent so much of his life hidden away in Baker Library, should have founded Betrayal (1967) and Groundswell (1968), two publications passionately attacking the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. What happened was that with friends in Hanover, Norwich, and Woodstock, they could no longer wave the stars and stripes and bless the enlightened effort to save South Vietnam from communists by enriching Vietnam soil with fertilizing black powder and to warm it up with napalm. For eight years in these brochures they have been sounding forth about their "sense of betrayal" for having voted for President Johnson because of his promise "not to widen the war." And later Nixon poured out billions of dollars and thousands of gallons of young American blood wastefully on foreign shores. Under both titles the main thrust keeps proving the cruel folly of American involvement in Southeast Asia. In New Hampshire, Vermont, New York City, and California the mail list keeps on increasing with a present peak of 500. Although articles cover a wide range of subjects (economics, politics, and philosophy), the central focus is on the disrupting influence of the Southeast Asian War on American society, stability, and solvency. Impelled by what Haile and Laing believe to be conscience and enlightened patriotism, they deplore the loss of 50,000 Americans killed "to save our honor." With intense dismay they view Ford and Rockefeller appeals, Nixon flavored, for more American millions for "just one more round" and thus keep alive corrupt regimes in South Vietnam and Cambodia. The latest issue, just out, may be obtained by writing to Box 84, Norwich, Vt., 05055.

The New York Times Book Review of February 2 gives J. D. O'Hara '53 a full-page spread for three novelists about whom you may have heard. How about Anthony Burgess, author of some 20 novels, including a trilogy? If unacquainted with his superior literary talent, you may tick with a flick, "A Clockwork Orange," that "slick, coarse, evil movie," emerging from his moral and religious novel of the same name. O'Hara reviews The ClockworkTestament or Enderby's End (Knopf, $6.95), which asks the same question as A ClockworkOrange: Because evil must exist to permit choice, a sign of our freedom and moral significance, what then will it be for you: "Die with Beethoven's Ninth howling and crashing away or live in a safe world of silly clockwork music?"

Kay Boyle is another author of some 20 novels. In The Underground Woman (Doubleday, $7.95) a 42-year-old widowed mother and teacher of a college course in Greco-Roman mythology finds herself, with many other women, involved in a protest against the Vietnam war. O'Hara considers the treatment to be somewhat old-fashioned, conventional, and idealistic. Kay Boyle's underground woman is "pale and sweet, no relation to Dostoevsky's underground man; and her novel is essentially feminine in its familial concerns, kaleidoscopic feelings, mythical rhetoric, and persistent subjectivity." Nonetheless it has value for "all sensitive and conventional women with bad consciences."

As a University of Connecticut English professor, O'Hara responds briskly to Monsieur by Lawrence Durrell (Viking, $8.95). The structures are "wilted." A doctor stupidly assumes that death masks require decapitation and that a decapitated head would not be buried with the body. A character about to retire had retired almost a year ago. A second character "snores through her mouth," and a third lies "spreadeagled on the sofa with his face in his arms." Still another "would stand against the wall and cry into the wallpaper, throwing her arm over those poor eyes." O'Hara hears of "a female stag" and someone's talk "literally drowned in meaning." The professor raises a quizzical eyebrow when he is told that cabdrivers would soon "be sauntered away into the town sleeping." The "monsieur" of the title, by the way, is the devil, and the novel is written in English, but O'Hara has an uneasy feeling that it is a bad translation from an unidentified foreign language.

What animal weak of sight, slow of foot, dull of wit, climbs trees, makes love gingerly, eats bark, and nibbles at your car tires because they may contain salt? A porcupine, of course. Why should this animal with about as much aggressiveness as an earthworm arouse such pugnacity in even the sweetest natured dog? And why cannot a smart dog, a sad and bloody sight as he paws violently at his mouth, nose, feet and even tonsils, densely filled with quills, ever learn that he is stupid to fight an adversary equipped with hundreds of quills varying in length from a half inch to five inches? These questions are answered with fascinating details in an article called "Dogs vs. Porcupines" with text and photographs by Shaun Bennett '70 in the November 1974 issue of Country Journal. And if you or, more likely, your vet does not tweezer out the quills? Bennett tells what happens when they hit bones, slide along muscles, form fibrous cysts, cause open wounds, and penetrate deeply in the body proper to pierce vital organs. He gives credit for much of the information to a highly respected naturalist in the Connecticut Upper Valley, George D. Wrightson DVM, of the Hanover Veterinary Clinic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

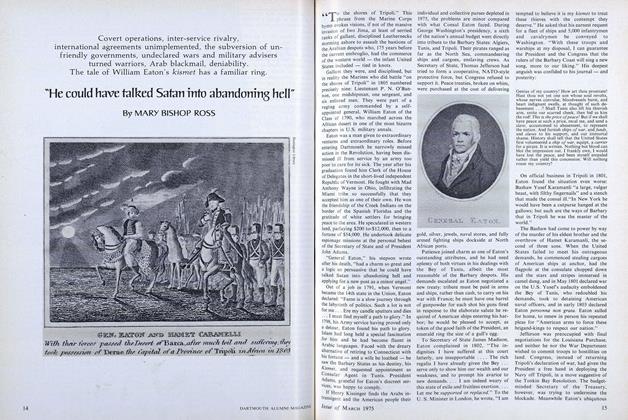

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

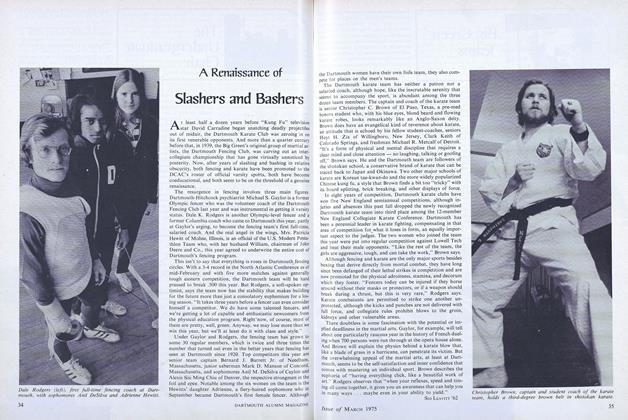

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

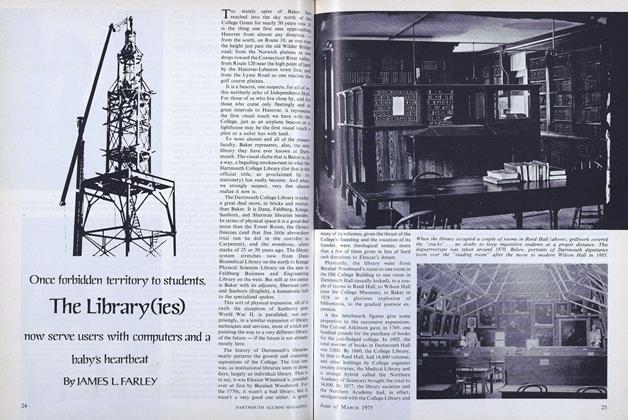

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

J.H.

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE DARTMOUTH MURDERS

January, 1930 By David Lambuth -

Books

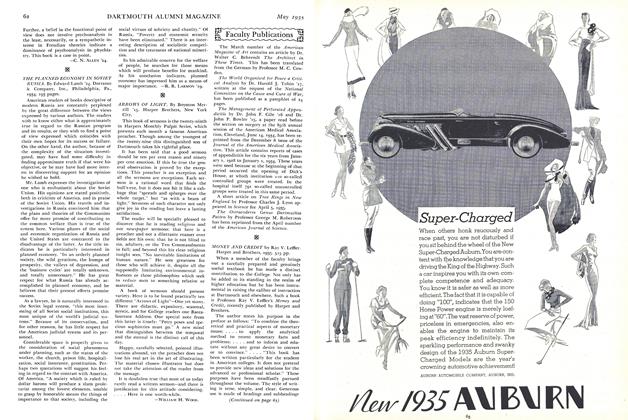

BooksMONEY AND CREDIT

May 1935 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksTHE RITTENHOUSE ORRERY.

October 1954 By GEORGE Z. DIMITROFF -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

JANUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksVASSI AND FIDELES IN THE CAROLING

August 1945 By John R. Williams '19 -

Books

BooksHOW TO GUESS YOUR AGE

June 1950 By Sidney C. Hayward