ADDRESS OF PRESIDENT HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SEPTEMBER 25, 1919

October 1919The association of the individual with the college cannot be held as a casual one by either without loss to both.

In consequence, at once in this opening exercise of the new collegiate year, even though there be not time to discuss it in detail, I wish to suggest the nature of this mutual relationship,—and its bearing upon our joint obligations to give help to our times !

The period has been, doubtless, in the long distant past, when the world was young and when society was without complications, that education was largely effortless and was acquired in the main through unconscious absorption. However, in the advance of civilization from its elementary forms to the more complex organization of modern society, the time early came which rendered a method of education impossible which had consisted largely of imitative processes. Progress is dependent on continuously increasing knowledge. The store of knowledge accumulated through preceding eras must necessarily be presented to succeeding generations in abstract if preparation is to be given for the search for increased knowledge. The trail laboriously blazed at first, and later cleared and widened, must be traversed with greatest practicable speed if it is to be to any extent lengthened.

Such is the philosophy by which the school of experience has been superseded by the formal institution of learning. This is the benefit that is available to men enrolled in the colleges over their fellows who have chosen or been forced to accept the method of practical experience instead of that of formal education. But it is a benefit that will only accrue as its opportunity is embraced. The mere fact of its existence or of one's propinquity to it will not profit one unless he uses his enrollment in the college as it is designed to be used, to give him such intimacy of contact with the advantage that he may make it truly a personal possession.

Membership in a college is a privilege, not a right. Hence it follows, and par in such a time of overwhelming demand as this, that the attributes should be specified which entitle the individual to inclusion within this privilege. This definition in the last analysis is very simple. It is not that a man should have the desire to go to college, even very greatly, nor that he should wish that he might at some time in the future be in possession of the certificate of having completed a college course. It is that a man should sufficiently value the opportunity which the college offers to utilize it in full. The time has come when it is plain that a man who will not accept the advantages which the college offers is monopolizing for a profitless end a place that another might fill to the present advantage of the college and to the future advantage of all affairs with which he should have to do.

It is one of the incongruities of college instruction and one of the idiosyncrasies of a Somewhat prevalent undergraduate point of view that so frequently successful avoidance of receiving what the college has to offer, for which the student is paying his time and his money, is considered a net gain to him rather than the net loss which it actually is. All in all, if by any stretch of the imagination this can be considered in any degree the joke which the undergraduate assumes it to be, the joke is rather grim and its ultimate effect is not upon the college.

The point cannot be too frequently made that in very large measure that period of adolescence encompassed within the confines of a man's college course is the plastic time when life's habits are being fixed. Throughout this time, habits of one sort or another are being formed; the only option is whether these shall be good or whether they shall be bad. If by deliberate purpose we do not fix within ourselves the habit of application necessary to hard work, the habit of soft living establishes itself. If we do not by determination force ourselves to accurate thinking, the habit of incomplete and unreliable thinking arrogates to itself a place in our mental equipment.

Tell a man that he is developing a batting form which will make it difficult for him to hit the ball, and he will show deep concern ; tell him that he is cultivating a trouble-making fault in his golf swing and he will give much time and money to the professional; but tell him that by disinclination to force himself to hard work or that by loose and indefinite thinking he is forming flabby habits of mind that will handicap him for life, and he will seldom give even his attention to the matter!

I am reiterating these points because in that long-distance event which we call life the pace is quickening and we are at the juncture where those will go into the lead who have supplemented their natural ability with acquired skill, who have by laborious training built up their stamina, and who by the elimination of faults have removed their handicaps.

I have been dwelling upon the obligation of the individual student who is admitted to the privilege of the college. However, none of us who have to do with the instruction or administration of the college are without consciousness of the heavy responsibility which inheres in the college itself. Education is not a static thing, apart from the occurrences of life. It cannot be left and returned to, ana found the same. It is a constantly developing process, in which must always be included consideration of the evolving problems which the given times impose. And never did times impose greater problems than are thrust before us now!

Despite the end of war we are not free from conflict. It is not yet as generally understood as it must eventually be how completely civilization is done with much that but little time ago we thought of as fixed and sure. It makes not the slightest difference whether this is or is not as we would have it; the fact remains that in the social and in the economic world as distinctly as in the political and the physical, old boundaries have been done away with and new ones are being drawn.

If in these realms we are to escape tragedy, if in seeking advantages of the new we are to avoid the loss of greater worth in the old; if in throwing down autocracies, at least capable, we are to avoid setting up ignorant despotisms; in short, when the rapid vibration of the present day resolves itself into something wherein direction can be defined, if civilization is to be found to have progressed rather than to have retrograded, it will be because of the domination which minds and consciences of men shall have gained over a disintegrating situation, which otherwise would have ended in chaos and in the loss of much which the world had arduously gained.

Civilization has escaped death by slaughter. It yet remains for us to safeguard that neither the listlessness of anaemia nor the fever of insanity shall work its end. At no time in the past has the need been so insistent nor the opportunity so great for the permanent advancement of the standards of civilization through the influence of the work of educational institutions of higher learning.

In such case, what of ourselves at Dartmouth! The general atmosphere about us today is one of auspiciousness and all the circumstances breed optimism.

The assured strength of the faculty, the tested and known worth of the undergraduates who have been members of the College before, the faith we have in the capacity of the newcomers to absorb and apply the better ideals of the College all tend to this result. We share, unquestionably, in the new increment of confidence which it appears the people of the land have set aside to bestow upon the colleges. The tangible and the intangible things alike give grounds for gratification to Dartmouth men and add a zest to the undertaking of our respective tasks never surpassed before. None would dispute our right to a measure of satisfaction and he among us who would forego this, denies himself that which he has helped to win and that to which he is entitled.

To an extent as great, however, the circumstances are such as peculiarly demand a common sense of obligation in behalf of this, our own college.

This phase of the situation demands uncommon emphasis at the present time and it is upon this phase that I urge the men of the College to give their best thought in the months before us. Because the work of the College has been found good in the tests to which it has been subjected,- it does not follow that it ought not to be far better! Because unprecedented approval is at hand for the accomplishment of the College so far, it is not to be concluded that we could or should escape scathing condemnation in the future if we failed to qualify to meet the vastly more onerous responsibilities that will be thrust upon us. Honorable and great as has been the completed record of the century and a half of Dartmouth's life, the due increase of the prestige of the College in the years immediately succeeding will be largely the reputation which men gathered here win for her and the criterion of merit which shall be ascribed to them will be the potentiality which the College proves capable of developing, to serve civilization amid its present perplexities.

With a personal seriousness, therefore, which is no affectation, and in behalf of my associates about me who are responsible for the formal education which Dartmouth offers, I beg the earnest solicitude and continuing effort of you men of the Dartmouth undergraduate body that this College, whatever increasing exactions shall be imposed, shall be in years to come, as in years gone by, not simply a name, but a great constructive influence, which shall so work and accomplish that neither the College as a living organism nor any individual touched by the fire of its spirit shall ever be found lacking, when comes the time of heaviest need or the occasion of greatest opportunity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

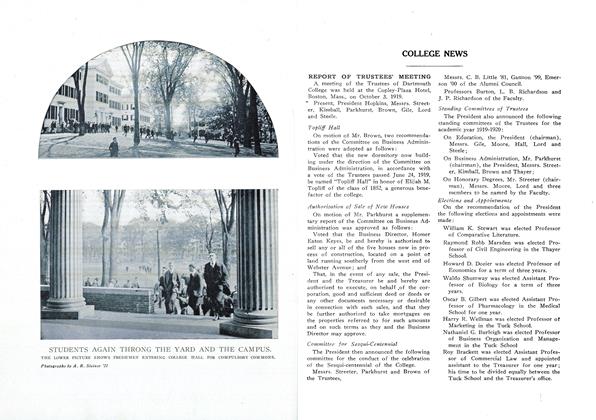

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleSALMON P. CHASE, UNDERGRADUATE AND PEDAGOGUE

October 1919 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleS. A. T. C. CONTRACTS AND THE COLLEGES

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleBIG INCREASE IN THE FACULTY

October 1919 -

Class Notes

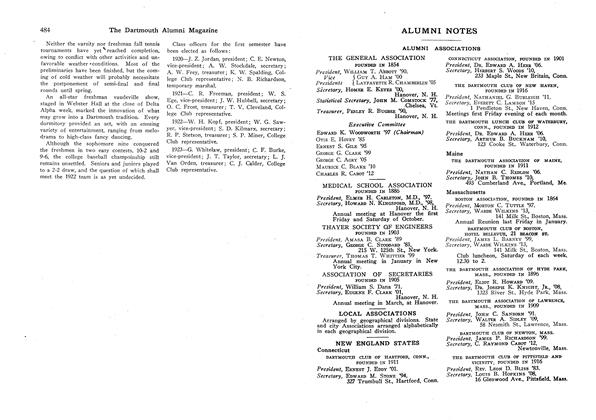

Class NotesNEW ENGLAND STATES

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF PROFESSOR JOHN VOSE HAZEN

October 1919

Article

-

Article

ArticleMr. McDavitt Honored

June 1938 -

Article

ArticleAir Corps-Non Flying Officers Administrative and Teaching Positions

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleHeads Business Group

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleEnquiring Minds

Jan/Feb 2012 -

Article

ArticleClass Notes

Sept/Oct 2002 By Fraser Smith '81 -

Article

ArticleFrom a 1908 Mem Book

March 1935 By L. W. G