"Chase", Abraham Lincoln once said, "is about one and a half times bigger than any other man that I ever knew." That Mr. Chase had a few very great faults, Mr. Lincoln had occasion to know better than anybody else in Washington. Nevertheless, that he should have placed so high an estimate on one who served him in the cabinet besides William H. Seward, Edwin M. Stanton and Gideon Welles, is an indication that the man had outstanding abilities.

The sesqui-centennial anniversary of the founding of the College draws natural attention to the career of Mr. Chase, whose effect on the history of the country so far as our graduates have influenced it, can be compared only with that of Daniel Webster. A small collection of manuscript letters written by Mr. Chase when in college and in Washington immediately after his graduation, has been recently acquired by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society.* Having been written to Mr. Chase's intimate friend, Thomas Sparhawk, they give some insight into life in college in the early '20's and into the mental development of Chase at a time when he was trying to find out how to invest the remaining years of his life.

Mr. Chase was born in Cornish, N. H., January 13, 1808 and entered college in 1824 as a junior, after passing the few superficial oral examinations of those days. During the first winter vacation he taught school, like many of his contemporaries, for seven or eight weeks, but showed no great enthusiasm for the profession of teaching.

The social life of the College occasioned far more enthusiasm and took up a much greater portion of his letters than the delights of teaching boisterous youngsters in a rural school-house. It appears for example, that the students formed a reading circle and invited certain young ladies, especially a Miss Williamine Poole who corrected any mistakes noticed in the course of the intellectual festivities. Miss Williamine seems to have devoted herself principally to .the improvement of the vocabulary of the circle. The precise character of her scholarly influence is indicated in Chase's letter of December 14, 1825:

"She has moreover acquired a number of smooth, elegant, pure harmonious, clear English sayings, par exemple 'You lie', 'Shoot your Granny', 'Awful critter' and I don't know how many others equipollent and tantamount to that. You see hereby what rapid strides Hanover is taking in the march of improvement."

During the following year, a religious revival first attracted the superficial notice of Chase and later enlisted his complete sympathies. "In the chapel this evening," for example, Chase wrote to Sparhawk in March, 1826, "you might have heard a pin drop so attentive and silent were the students. The revival commenced among the young ladies, all of whom without exception have become seriously disposed. The president is indefatigable in his labors to promote its spread and he is seconded tho' with less ardour by the other officers of college."

After graduation Mr. Chase went to Washington and set up a private school. His uncle, Dudley Chase, was at this time United States Senator from Vermont and through his influence the young graduate gained the attention of many men of national importance and influence. Several of these, notably Henry Clay, gave Mr. Chase their assistance in obtaining students. At one time Chase had in his little school the children of all the members of the Cabinet except one. These were busy days for a man who was struggling in one profession and hoping soon to enter another, and who must meet also the demands of society. During the day he attended to his duties as a pedagogue, dropping them to take up his law books, and in the evening he enjoyed the pleasure of Washington society. His days were long and laborious, beginning at daybreak and ending at eleven at night.

He was a frequent visitor in the home of William Wirt, who was at this time concluding a long term as attorney-general of the United States Whether the magnet at the home of the attorney-general was the store of legal erudition which Mr. Wirt possessed or whether it was the presence of five interesting daughters, Mr. Chase does not make clear.

He does make clear, however, the mental strain through which he was going in politics. It was in 1828 that Andrew Jackson was elected to the presidency over John Quincy Adams, nullification was on the horizon in South Carolina, and Mr. Chase was in great distress. The "millenium of minnows" had come, he declared. Moreover a brother of the younger Mrs. Adams was to be married to his sister's serving maid. Society was being turned upside down. The nation was going to ruin at top speed. Hence it was a Chase that poured out his fears to Sparhawk on November 10, 1828:

"You have ere this learned the result of the Presidential contest. The People have made choice of King Dragon and we must be content to abide the consequences. If I do not mistake the signs of the times you and I will live to see this Union dissolved & I do not know that New England has much reason to deprecate such an event. The proceedings at the South during the last summer, the measures adopted as preparatory, by the South Carolina delegation in Congress, last winter, and the recent election of an ignoramus, a rash, violent military chief to the highest civil office are fearful omens of approaching convulsions. It is my hope that Genl. Jackson will disappoint the fears of his opponents but I hope with much apprehension. Time, however, will shew and till then I trust the People of the North will hope for the best and prepare for the worst."

"The day has past, I fear forever past in this country, when a man will be rated according to his intellectual strength, extensive experience or moral excellence."

Mr. Chase was, however, far too healthy a young man and possessed of far too vigorous a mind to remain long in the slough of discontent and pessimism. He continued to study the law at any intervals that presented themselves and in December, 1829, he was admitted to the bar. Shortly thereafter he went to Cincinnati, Ohio, to begin the practice of his chosen profession. Thirty-five years before Chase went to his new home, the site of the city was a forest, broken here and there only by the cabin of a squatter. But in 1830 the outlines of a bustling metropolis had been drawn.

"The canal comes in from the north, and is covered with boats. We close our eyes for a moment and listen. We hear, from the river, the roaring of the stream; from the canal, the notes of the bugle; and from the entire city, that confused noise of the rattling of wheels and the jar of machines, and the clamor of voices, which always indicate the presence of a multitudinous population. We open our eyes again and we almost imagine that we see the city grow. We do see all the symptoms of vigorous growth. There are factories, more than we saw when in the valley, and in every part of the city. There are many churches, some of them grand in their proportions and splendid in their architecture. There are the residences of some of our private citizens that show like palaces. There are extending streets and multiplying erections of every description, on the two levels, that, with the connecting declivity between them, form the area of this vast amphitheatre. There are the markets, not quite so neat fabrics as they might be, but filled to the overflowing with the abundance of the surrounding country, and crowded by the great multitude who live to eat, or eat to live. There, too, is NOT—alas! that we must say so—a CITY HALL worthy of the greatness and opulence of our city."

From this time on Chase was full of hope and optimism. The world was no longer all bad. The energetic bustling West, not over-modest about its present and enthusiastic about its future, gained the affection of Mr. Chase and indeed mirrored the qualities of 'the man himself. He no longer had any desire to return to New England but decided to grow up with Ohio. His face was now set to the future and to the career that would make him "one and a half times bigger" than any other man that Lincoln ever met.

*A copy of these letters edited by Professor A. M. Schlesinger has been recently added to the College Library.

Charles R. Lingley, Ph.D., Professor of History in Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS OF PRESIDENT HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SEPTEMBER 25, 1919

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleS. A. T. C. CONTRACTS AND THE COLLEGES

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleBIG INCREASE IN THE FACULTY

October 1919 -

Class Notes

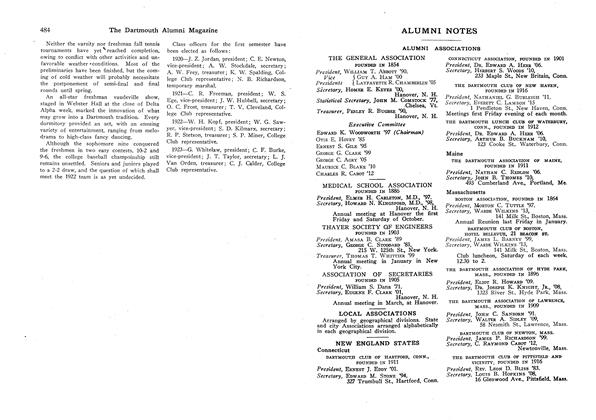

Class NotesNEW ENGLAND STATES

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF PROFESSOR JOHN VOSE HAZEN

October 1919

Charles R. Lingley

-

Books

BooksThe Life of Thomas Brackett Reed

By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

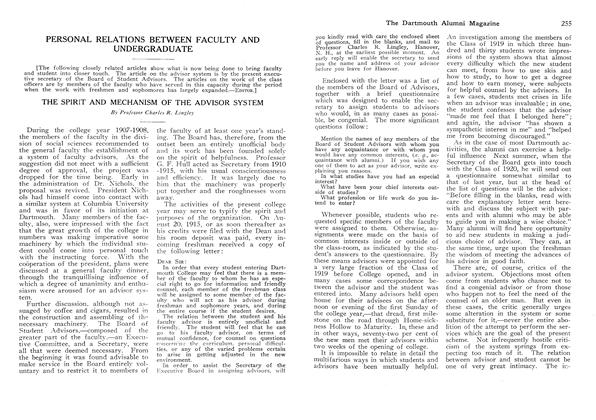

ArticleTHE SPIRIT AND MECHANISM OF THE ADVISOR SYSTEM

April 1916 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

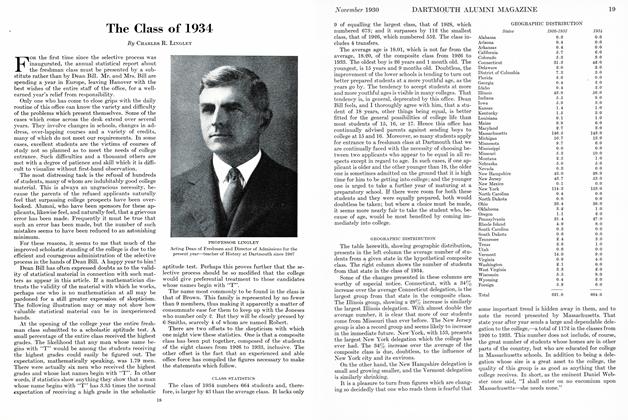

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

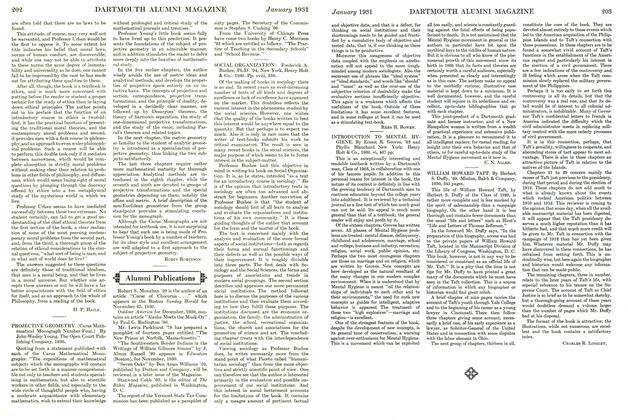

BooksWILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

January, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

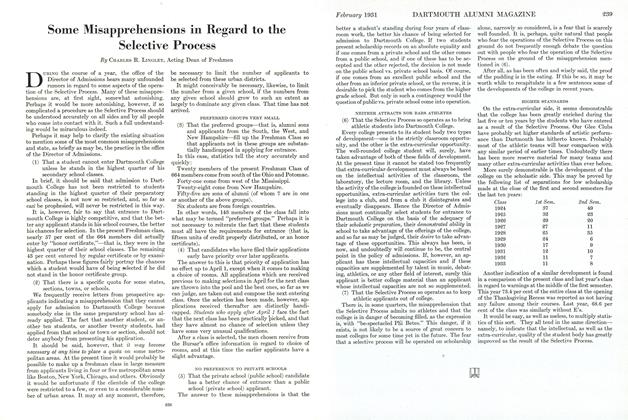

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleRichardson's New History of the College*

MAY 1932 By Charles R. Lingley

Article

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL FALL MEETING OF TRUSTEE BOARD

December, 1925 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth-Wellesley

OCTOBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

NOVEMBER • 1985 -

Article

ArticleMORE ACROSS THE RIVER

DECEMBER 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

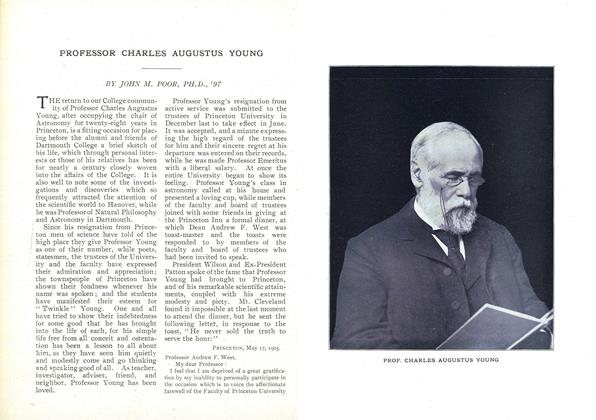

ArticlePROFESSOR CHARLES AUGUSTUS YOUNG

OCTOBER 1905 By JOHN M. POOR, PH.D., '97