Dartmouth’s sesqui-centennial observance has taken its place in the lives of more than seventeen hundred undergraduates as the outstanding college event of their day, and has been added to the treasury of alumni tradition as one of the significant incidents of Dartmouth’s history. As aged men tell of the centennial celebration, and younger ones of the Webster centenary, or the visit of the Earl of Dartmouth and his laying the cornerstone of new Dartmouth Hall, or the inauguration of a president of the College, as a central experience- which made a permanent impression upon them in undergraduate days and around which memories of college gather in the pass- ing years, so these young men of the present will recall beautiful October days in their time when the alumni came home, and the college world sent its strong men to clasp hands with Dart- mouth, and all together they stood for a little while on the Mount of Vision and saw a great past and a greater future. For this too was one of Dartmouth’s milestones, a real event in a history that is rich in inspiring event.

The 150 th anniversary of the granting of a charter for Dartmouth college by John Wentworth, colonial governor of New Hampshire, to Eleazar Wheelock, the unchanged charter of the present day, was celebrated on October 17—20. Dartmouth Night, on Friday the 17th, was followed by a day of recreation, sports, amusements; this by one of re- ligious observance, fraternity reunions, impromptu class meetings, and that form of worship which is inspired by music. Then, on Monday the 20th, the “great day of the feast”, came the for- mal celebration.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 17

All day Friday, dwellers along the state roads leading up from Boston saw automobiles bearing banners of green and white, inscribed with a legend tell- ing them that the Boston alumni were on their way to Dartmouth. If all the home-coming alumni had been similarly provided, dwellers on all the roads and travellers on all the trains would have known that Flanover was the center to- ward which men were moving from many cities and states. They came from all directions, many of them from far away, and in great numbers. There is no complete record of alumni attendance—• although an attempt was made to get a registration. Hundreds forgot or did not think to register, yet some idea of the size and completeness of alumni repre- sentation at the celebration may be ob- tained from the fact that 443 Dartmouth men left their names with the registrars at College Hall, and that even this in- complete list contains members of every class back to 1870, some who were at Dartmouth in the 60’s, and one at least, Benjamin A. Kimball of the trustees, who linked the celebration back to ’54. The class of ’O6 had the largest registra- tion, 91.

All the visiting alumni were not pres- ent on Friday night, of course. Not all who came later remained throughout the celebration after their arrival. There was a constant coming and going. But a good many were present when the cele- bration began. Even on Friday night the accommodations provided by emptying Massachusetts and North Massachusetts Halls of undergraduates, were pretty well taken up, the regular occupants of the dormitories, by the way, doubling up with friends in other buildings, or sleep- ing in the gymnasium, where 250 army cots had been placed. Besides, the homes of Hanover had been opened, and even in neighboring towns in New Hampshire and Vermont there were anniversary visitors. The Inn, of course, was filled.

So it was a great throng of Dartmouth men that gathered on the campus for the opening event of the celebration—Dart- mouth Night.

Dartmouth Night

It was a dark night, that Friday night, the 17th, and seemed the more so be- cause of the brilliance of the electrical outline of the cornices and pediments of Dartmouth, Wentworth and Thornton Halls, and the dull glow of the great tent which stood at the southern end of the Green. Out of the darkness came sights and sounds dear to Dartmouth men. A few flickering torches and the strains of a military march told that the College band was approaching at the head of the undergraduates, picked up group by group as the lengthening procession wound its way among the college halls by a . route marked by green flares. Then came a Wah-Hoo-Wah crashing through the dark from somewhere, and another, and then another, as the torches of the band drew near the Green and the un- dergraduates came on to escort the alumni in the Dartmouth Night parade.

As the line passed up the Campus, torches were distributed to the marchers, and suddenly the dark procession blos- somed out in dancing, fancy-touching light.

Turning at the White Church, the torch-bearers countermarched to the Inn, there to cheer, class after class, Gen. Joab N. Patterson ’64, of Concord, the honorary marshal, who was a marshal upon the occasion of the celebration of Dartmouth’s centenary in ’69. The Gen- eral stood on the Inn veranda, reviewing the long parade, and responding as cheer after cheer arose in his honor.

Then the marchers went to President Hopkins’s house, cheering as they passed it, and thence to the tent on the campus, the Rollins chapel peal ringing, the while.

Here let it be said that the one note of sadness in the entire celebration was heard at the outset. There could be no marching past Dr. Tucker’s home. Throughout the anniversary event the beloved leader of Dartmouth men was ill—too ill to receive callers, or even per- mit of telephone calls to his house.

But this sadness existed only as an undertone. It was present, and the note was heard from time to time, but from first to last the celebration was a sym- phony of rejoicing and confident faith. When Dr. Tucker’s name was spoken on that Dartmouth Night, it was cheered as if he were there to hear it.

It is estimated that the tent in which the Dartmouth Night exercises took place had a seating and standing capacity of 3,000. Upon that basis, a calculation of the attendance would arrive at just about 3,000. And, as it turned out, that large company was “in-tent” upon more than a good time—the pun being charge- able to no less a person than the chair- man, not the writer. There was one pres- ent who is almost a stranger at Hanover, although not to Dartmouth men. Not being familiar with the ways of college gatherings, he asked one of the profes- sors what Dartmouth Night was to be like.

“Dartmouth Night,” was the facetious reply, “is the night when we thank God that we are Dartmouth men, and are not like other men. There will be speaking, and singing and cheering. And when the formal program is over, we shall have a ‘sing’. It is a great, jolly, get-together”.

So the stranger was prepared for a night of unfettered jollification. Well, it was a stirring night, but its prevailing tone was serious, not somber, but ser- ious. There was cheering in plenty, and it was vibrant—and there was singing, too, but when the addresses had been given, and The Dartmouth Song had been sung, the audience melted away. Yet there was no least feeling that Dart- mouth Night had failed. This same stranger heard scores of men say that it was the finest they had ever attended, and some of these have been present at many Dartmouth Nights.

President Hopkins presided. Just as he was about to open the exercises, for- mer President Ernest Fox Nichols arrived in the tent, and went to the plat- form amidst the ringing cheers of the undergraduates and alumni.

The President produced a sheaf of congratulatory telegrams from a harvest of them, and read a few. One was from Paris, from Edward Tuck, a message full of faith and pride in Dartmouth on “its hundred and fiftieth birthday, at the zenith of its fame and success, with its future never before so full of promise”. This was character- istic of the entire celebration. Dartmouth has a great past, but isn’t living in it. It celebrated an event of 150 years ago, but did it chiefly by looking nobody knows how many years ahead. If there was an anniversary theme, it was “Preparation Today for the Work of Tomorrow”. The past was recalled as a source of in- spiration for the future.

But to the telegrams. One came from the Ohio alumni, another from the Epis- copal convention then in session, in which there were numerous Dartmouth men. The Hartford, Connecticut, alumni also sent a fine message from the state whence Wheelock came to New Hamp- shire, and which provided him with his first class of freshmen. That was exclus- ively to the Class of ’23.

And there was a ringing word of fel- lowship from Atlanta, Ga., where the first meeting of Dartmouth alumni south of the Mason and Dixon line was in session. “Dartmouth is marching through Georgia from Atlanta to the sea” was the cheer-provoking message that came from the South.

Of different significance was a note- worthy message of congratulations and commendation from the federal Bureau of Education at Washington.

These are not all the President read, but they are typical. The reading of them was followed by the presentation of General Patterson—he who had already been cheered by the marchers, and who was greeted with another fine demon- stration.

The first speaker was Samuel L. Powers ’74, of Boston, former congress- man. He was present at the centennial celebration, and recounted some of its incidents. Coming swiftly down the inter- vening years, he compared and contrast- ed the college of the past with that of the present, and then went on into the future, in his swift course turning away from the men of the past, and address- ing his message to the Class of ’23, and calling it to the Dartmouth service.

Matt B. Jones, ’94, was next on the program. He, like his predecessor, drew from a fund of happy Dartmouth mem- ories, and began his remarks with pleasantries. But the president of the New England Telephone and Telegraph company passed quickly from mere en- tertainment to the serious matters that he wanted to talk about. As he spoke, one got the impression of a man of af- fairs, in the thick of big business and big problems, stopping for a moment to help some youngsters put on their armor for the struggle in which he already was en- gaged. Matt Jones has the faculty for direct expression. He exercised it that night, and in simple, straightforward talk, he defined the Dartmouth spirit in terms of character in such a way as to stir all the better impulses.

He was followed by David J. Malo- ney, ’97, of Boston, who also gave a ser- ious, heart-to-heart talk to the younger undergraduates on the making of the Dartmouth type of man, and the obliga- tions to serve the college in the coming years.

Here, at the close of the Boston attor- ney’s fine address. President Hopkins called for such a cheer as had never be- fore been given at Dartmouth, for Dr. Tucker, telling of the illness of the greatly loved former president, and ex- pressing the general sorrow over his en- forced absence from the anniversary ob- servances. The cheer that followed may be left to the imagination of those who did not hear it.

The last speaker on the program was Benjamin T. Marshall, ’97, president of the Connecticut College for Women. His address was an interpretation of _ the Dartmouth spirit as manhood, brother- hood, sympathy and service. In its course he referred to the staunch sup- port of the college given by the Boston alumni.

President Hopkins spoke briefly, and like all the other speakers, his words re- lated to the future. At the end, however, he carried the forward-looking company back to the beginnings, by calling for a cheer for Eleazar Wheelock. It was given, but the cheerleaders wouldn’t per- mit matters to rest there in the middle of the eighteenth century, and there was another for Prexy Hopkins. The Dartmouth Song was sung, and

the audience was dismissed. As it emerg ed from the tent, it was into light, not the usual darkness of the Campus. All along the northern end of the Green fireworks were being set off. So ended Dartmouth Night. And at the Inn and in all the places where the alumni gathered for good night sociability, one heard over and over again that it was one of the best—a serious, thoughtful, earnest night, calculated to leave a deep and last- ing impression upon the boys of 23, to whom most of the remarks had been addressed.

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 18

It had seemed as if pretty much all the Dartmouth world had arrived at Han- over on Friday, but Saturday was an- other day of home-coming for Dart- mouth men. All day long they came and from far and near. This was a day of in- formal reunions, of inspecting the col- lege buildings, of social gatherings, one of them being at Moose Mountain Ca- bin, of football—quite memorable foot- ball, _by the way. And in the evening, a revival of “The Founders” was given.

Throughout the morning hours there was a steady stream of guests pouring in and out of the newer buildings. Many of the alumni hadn’t seen the newest of these, and to some a good deal of the present day Dartmouth was new. A few, too, were accompanied by their wives, for although accommodations did not permit a general invitation to the ladies, some of the alumni brought their wives, and obtained lodgings in private homes or in the nearby towns.

There was another attraction, too. The golf links called to some of the alumni. And as the morning wore away, there was somewhat of an exodus in the direc- tion of Moose Mountain. For a roast pig barbecue was in preparation there, thanks to the Rev. John E. Johnson’s generosi- ty, and Professor Leland Griggs and a committee working with him had ar- ranged for a pilgrimage to the favorite mountain shrine of the Outing Club. It is said that provision had been made for a hundred and fifty guests, that three hundred hungry Dartmouth men re- sponded to the invitation, and that all returned to the college in a Charles Lamb frame of mind with reference to roast pig. It has not been suggested that there was a miraculous multiplying of the pig, so the supposition is that the arrangements had the quality of elastic- ity. At all events, it apeared to be a sleek and satisfied crowd that got back to Hanover for the football game.

That game won’t be forgotten soon. Mention Penn State to anybody who was at Hanover for the anniversary and you will awaken memories of a mighty cheer that rose higher and higher as the ball which Dartmouth had kicked off sailed up towards the gymnasium, and then began to die away as the ball fell into the hands of a Penn Stater by the_name of Way. And it kept right on dying as this same Way got his stride, ducked, dodged, and went through obstacle after obstacle, and with the aid of some first- rate interference got out into open coun- try and fetched up behind the Green goal posts. This wasn’t the last cheer, how- ever.

But the story of that game need not be repeated here. Let it suffice to say that Dartmouth got the lead by steadily pegging away at the line, only to lose it again when Way got a fumbled ball on his 15-yard line and ran the length of the field for another touchdown. Again Dartmouth scored by steady gains in the line, and in the third period Hol- brook broke through the Penn State de- fense in midfield and scored after a run that did something towards matching Way’s performances. There were other tense situations and nerve-racking plays, Penn State holding for downs twice and getting the ball on its own two-yard line, for example. But Holbrook’s long run settled matters, and the game ended with a 19 to 13 win for the Green.

It need hardly be said that one of the biggest football crowds ever assembled at Hanover saw the game, the stands that extended the length of the field on both sides being filled and both open ends be- ing densely packed.

On Saturday night the Dartmouth Dramatic and Musical Clubs occupied the stage, literally as well as figuratively. “The Founders,” first in the long series of Dartmouth undergraduate musical plays, was chosen for the anniversary theatrical performance, and was well played before an audience that filled Webster Hall. Merely to mention “The Founders” is to recall to all Dartmouth men a tuneful operetta, the product of James W. Wallace ’O7, Harry R. Well- man ’O7, and Walter C. Rogers ’O9. Up- on this occasion Professor Wellman directed the orchestra.

“The Founders” is full of vigor, moves along with a swinging stride, and is full of Dartmouth tradition and of the music that lives at Dartmouth. The an- niversary revival brought it all back again, fresh and living.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 19

For all the magnitude of the anniver- sary gathering, the coming of new arriv- the flitting hither and thither of in- dividuals and groups in quest of friends, or for class and fraternity reunions, the indefinable calm and charm of a New England Sunday pervaded Hanover on the third day of "the celebra- tion. Perhaps the founder would not have recognized in the present day equivalents of ancient forms an expres- sion of reverence, but no reference to calendar or program was necessary for present day men to know that this tran- quil day was the first of the week.

The Anniversary Sermon

. Of course, this was the day of the an- niversary sermon, preached in the White Church by the Rev. Dr. Ozora S. Davis ’B9, president of the Chicago Theolog- ical Seminary. Not all attended the serv- ice, but all who could get into the church were present.

Dr. Davis’s text and theme was the Dartmouth motto: “Vox Clamantis in Desertc”-—his sermon was an exposition and application of the entire passage in which the words occur. The “voice of one crying in the wilderness” was that of Isaiah, “prophet of hope in a time of exile”; that of John the Baptist, “pro- phet of righteousness in an age gone stale with religious formalism”; that of Eleazar Wheelock, “prophet of learning and civilization in an age of wide and mighty beginnings.” The ages passed in review as Dr. Davis preached, and the strong men of the ages—“a captive under the iron hand of the Assyrian ter- ror, a rough man of the wilderness strik- ing his axe hard at the root of contem- porary sin, a pioneer minister and teach- er.”

In the words of the preacher, the an- niversary sermon was an attempt to re- value the ancient Scripture incorporated in the college seal. The wilderness of Wheelock’s day was portrayed, the wilderness in which his voice was raised, not alone the material one, but also that to which the vox clamantis was ad- dressed, “rude, undisciplined, confusing, dangerous, alluring, big with romance, potential, mighty,” and swiftly, deftly, the preacher passed down to today, and today’s world wilderness.

“It holds the promise of the riches that support civilization,” this wilderness of the world, said the preacher. “The wilderness is not for the undoing of man. It is for his making. In subduing it, he realizes himself.”

Then the wilderness messenger was portrayed, and his message—the latter “cast in the royal figure of a king’s pro- gress through his realm.” This was the thought in Wheelock’s mind, said Dr. Davis, “when he placed above the col- lege building on the seal two Hebrew words, “El Shaddai”, God Almighty. “The one central thought of these wil- derness pioneers was that God Almighty is moving through His world and it is man’s business to make His way ready and straight.”

Those familiar with the Scriptural passage—who are not ?—can find the rest of the way through this powerful sermon, the royal path of service over which men go to fill the valleys, make plain the rough places, and prepare the way for the full revelation of God in the assurance that in the end the vision will come to all.

But no mere abstract of this sermon is adequate or in any degree satisfactory. Even the full text would fail to impart what Dr. Davis gave of himself to the anniversary congregation. It was a fine sermon, preached greatly.

Sunday Afternoon and Evening

Between the anniversary sermon and vespers, there was nothing on the formal program, but every moment of that time was compact of the stuff of the anni- versary for hundreds of Dartmouth men. It was in these hours that most of the fraternity and class reunions took place, although others occurred from time to time throughout most of the an- niversary period, as classmates met, or as some energetic classman discovered from the registration that enough of his year’s men were present to make a re- union, and set about getting them to- gether. But on Sunday afternoon, in all the fraternity houses there were gath- erings, large or small, formal, or infor- mal. Noteworthy among these was the gathering of Theta Delta Chi, at which a tablet was unveiled in memory of the men of the fraternity who gave their lives in the War of the Nations.

Throughout the afternoon, too, there was steady access of attendance, many of the representatives of the older east- ern colleges arriving to take part in the central event of the celebration on the following day. By this time, the anni- versary assemblage was virtually com- plete, and while it could not be seen at one place or time, one could not but be impressed with its character, the breadth of its interests, and the loyalty and af- fection for Dartmouth of these men from far and near, from the forum and the pulpit, from the office and the count- ing-room, from college halls and from industry, governors, senators, congress- men, educators, preachers, men from all the professions, and great vocations.

In the afternoon of Sunday, the skies became overcast, and a light rain began to fall, the only period of unfavorable weather in all the anniversary days. Even this was not damaging or even dampening, the rain being little more than a drizzle, and really having no effect at all other than that of promoting the sociability at the Inn, the fraternity houses, and the dormitories.

At 5.30 o’clock, there was a large gathering for the vesper service at Rol- lins Chapel. President Hopkins con- ducted the service and gave a brief ad- dress which, as was the entire program, was of the warp and woof of the anni- versary fabric.

After vespers, the delegates, guests of the college, their hosts and hostesses, as- sembled in Robinson Hall, where a buf- fet supper was served. It was a note- worthy gathering. The guests had for the most part arrived in Hanover by this time, and most of them were at Rob- inson. It was interesting to watch the kaleidoscopic re-grouping of men and women, here for example, around Judge Stafford of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, who was to be one of the speakers on the morrow; there around President Hetzel of the State College, yonder around Governor Bartlett, and not once but many times around President Hopkins himself as he welcomed the men who had come from other colleges to join in Dartmouth’s festivities. Interesting and inspiring it was, too, to join in the earnest, thought- provoking conversations, and to observe how often these turned towards the sub- ject of industrial relations, as if the one great problem of the day were press- ing in upon Dartmouth from all sides as to a center where a contribution is to be made or is being made to its solution.

The closing event of Anniversary Sunday was an organ recital at Rollins Chapel, on the Streeter organ, by Harry Benjamin Jepson, Professor of Applied Music and University Organist at Yale University. It was attended by a large and appreciative audience.

So ended Anniversary Sunday, a day of worship and of reunion, closing with the high thoughts inspired always by the musical instrument created for and characteristic of the Christian Church, under the hands of a master. As the night wore on, the rain still fell, but lightly.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 20

The morning was crisp and cloudless. The sun, rising directly over Dartmouth Hall, was the first and most welcome of sights that greeted the eyes of the alum- ni as they left the Massachusetts Halls for breakfast, the last of the Anniver- sary Day visitors to return after a brief absence on Sunday, bringing all that was needed to make the event of the day perfectly enjoyable. The misgiv- ings of the rainy Sunday night disap- peared. In the sweet, cool air and the flawless light of a New England autumn day at its best, the men of Dartmouth met on that anniversary morning as they hurried through the necessary business of the early hours with only words of buoyant good cheer.

This was the high day of the observ- ance—Anniversary Day—to which all else had been preliminary or incidental. This Monday, October 20, was the day when Dartmouth stood with the repre- sentatives of the state whose charter it holds, and of the great fellowship of the college, remembered its great past, and looked forward with faith as clear as the light that flooded the Campus.

Swiftly the sunrise scene changed. In place of hastening breakfasters, came figures in cap and gown and hood, fa- miliar, some of them, others known only to a few and pointed out as the repre- senatives of other colleges or the great universities. At first they moved about as if to no central purpose, but gradu- ally a definite current in the direction of Rollins Chapel became observable. There those who were to take part in the academic procession were assembling for morning prayers.

And right here let one of the innum- erable incidents be recorded. Among the guests was one who is just rising to prominence in New Hampshire, one whose education and life work have been in other than the Dartmouth circle. The writer greeted him at the chapel en- trance, and observing a characteristic manifestation of unusual interest in his expressive face, asked by the merest look what it was that had laid hold upon him.

“It is the finest company of men I ever saw,” he said, and turning he passed into the chapel.

The Academic Procession

The academic procession was to all intents and purposes formed in the chap- el. Admission was by numbered ticket, the holders sitting so that as they left their seats those who were to march side-by-side met each other in the aisle. The brief service was conducted by President Hopkins, and at its close the marshal’s staff directed the forming of the long line, which, headed by Nevers’ band of Concord, stretched away from the chapel, past Webster Hall, and to the White Church.

It was a noteworthy company indeed, a cross section of educated America. Worthy of note it is too that in it were two descendants of Eleazar Wheelock, Edward Wheelock Runyon and Walter C. Runyon of New York. While the procession is forming, make a note of this incident of the anniversary. The line that binds the founder to the anni- versary in a tie of blood runs: Eleazar Wheelock, the Founder; James Wheel- ock, his son; John Ripley Wheelock, son of James, a graduate of the college in the class of 1807; Mary Wheelock, daughter of John Ripley Wheelock, born at Hanover 97 years ago, and her sons, Edward Wheelock Runyon and Walter C. Runyon. These brothers have a sister whose son, Wheelock Jahn, was graduated from Dartmouth in T4.

But to the procession; it has begun to move in the time passed in making the acquaintance of Eleazar Wheelock’s de- scendants. At its head is the honorary marshal, Gen. J. N. Patterson, he who was the active marshal a half century ago; and beside him the marshal of to- day, Professor Eugene Francis Clark, the College Secretary. Here is President Hopkins, and beside him Governor John H. Bartlett. It is one of the appropri- ate incidents of the anniversary that after a century and a half it is once more a Portsmouth governor who is associated with the President of the College in the affairs of Dartmouth as at the beginning it was a Portsmouth colonial governor, John Wentworth, who was associated with Wheelock in laying the broad, deep and lasting foundations of the college, foun- dations laid in such fashion that while College and State are separate they are intimately and necessarily related. '

President and Governor are followed by the trustees and some of the admin- istrative officers, each escorting one of the speakers of the day or some distin- guished participant in the exercises—for example, Gen. Frank S. Streeter accom- panies former President Nichols, Lewis Parkhurst accompanies President Bur- ton of the University of Minnesota, and so on.

Follows the Alumni Council, arranged in academic seniority, then come the guests of the college. The members of the governor’s council are next in the line, then the state officials—President Arthur P. Morrill of the Senate, Speak- er Charles W. Tobey of the House of Representatives, Chief Justice Frank N. Parsons of the Supreme Court, members of the New Hampshire Board of Educa- tion and the Department of Education, and others.

Then the Town of Hanover appears, its town officers being in the line, and after them the representatives of Amer- ican colleges and universities arranged in the order of academic seniority; Har- vard, William and Mary, Yale, Univer- sity of Pennsylvania, Princeton, Colum- bia, Brown, Rutgers, North Carolina, Williams, and many more.

Then come the Dartmouth faculty, and at last the alumni, arranged by classes so far as this is practicable.

The procession, in all its academic glory of cap and gown, and multi-col- ored hoods, American and foreign, marches around the Campus before a great company, and under the searching eyes of cameras. At Webster Hall the commencement custom is observed, the double file of seniors opening out and forming an aisle through which the remainder of the procession passes into the hall.

The Anniversary Exercises

The anniversary exercises opened with the “Mignon” overture, played by Nevers’ band, seated in the rear of the dais. The invocation was offered by the Rev. Dr. Francis Edward Clark, presi- dent of the World’s Christian Endeavor Union.

Felicitations were offered in the name of the undergraduates by Herman Wil- son Newell ’2O; for the faculty, by Dr. Edwin Julius Bartlett, New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry; for the alumni, by William Tabor Abbott ’9O,_ President of the Association of Alumni; for the fellowship of the colleges, by Dr. Fred- erick Scheetz Jones, Dean of Yale Uni- versity; and for the State of New Hampshire, by Governor Bartlett, whose introductory words were:

“To Dartmouth, now a nation-wide college, the state of New Hampshire, which coveted her when a child and sought to adopt or ab- duct her, after a century of generally mutual friendship and prosperity, clothed in due hu- mility for its earlier sins, not vaunting its occasional and modest benefactions, comes to this, her natal festal day, figuratively bearing its many-candied birthday cake, bringing all ,its floral acres, all its forests of divinely painted beauty, and speaking the love of half a million warm and admiring hearts.

“During these years, through the college the state has, from its sister states, received within its jurisdiction thousands of stalwart men who have left their valuable imprint upon us, and then borne back to the world something of this, the state of their alma mater. We welcome such here now again to the hospitality of our commonwealth.

Next on the program was the Anni- versary Ode, given by the college glee club and orchestra. The words are byUr. Francis Lane Childs ’O6, Assistant Pro- fessor of English; the music is by Leon- ard Beecher McWhood, Professor of Music. The Ode is as follows.

Dartmouth, old Dartmouth,Your so,ns have come home!From the ends of the earthTo your halls in the NorthYour sons have come home,'—Come home!

Your sons!

You have mothered them all;

With your strength you have fed them,

With your wisdom have taught them,

With your love you have blest them

And sent them forth;

Bidding them go where life should run quick- est,

And men should be needed to lead in the combat

Undaunted, untamed as the winds that blow Through the pines on the hill where you watch o’er them yet.

Dartmouth, old Dartmouth,Your sons have come home!Prom the ends of the earthTo your halls in the NorthYour sons have come home,-—Come home!

Your torch that you kindled in faith for the eldest

A hundred and fifty winters ago, A wilderness guide for your Indian sons, Has burned to a beacon flaming so far That your youngest have seen it in France and in Flanders,-

Have seen it and known that your watch is still set

In their home in the North; And whispering your name have given their lives

In courage and strength, as you bade, for the truth.

O mother of men, blest are your sons!

Dartmouth, old Dartmouth,Your so,ns have come home! _From the ends of the earthTo your halls in the NorthYour sons have come home Come home!

There were three addresses in _ the course of the anniversary exercises, made by Judge Wendell P. Stafford, As- sociate Justice of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia; • Dr. Marion Le Roy Burton, President of the Uni- versity of Minnesota; and President Hopkins.

Judge Stafford’s theme was “The College a Training School for Public Service,” his address was an interpre- tation of the inner life of the college as distinct from its buildings, laboratories, campus and gowns; an illustration, and an application of the idea of college training as means to an end.

Oddly enough, the speaker went out- side of college walls for types of the col- lege considered as its intellectually trained men who have made the riches of the past their own, used them for the general good, and thus expressed the col- lege ideal, in the lives of Abraham Lin- coln and Keats, the latter “as innocent of Greek as the new curriculum assumes all men should be,” yet who wrote po- ems more Grecian than the Greek. His illustrative types gave force to his first proposition that the soul of the college, that which would “keep on its way, making new instruments for itself to work with,” even if all things material were lost, is a determination “to culti- vate and discipline our powers, with the aid of all that men have learned before us, and then to pour the whole stream of our power into the noble tasks of our own time.” It is in the college that “the determined spirit finds a tool shop and arsenal.” And continuing:

“Now it is the glory of Dartmouth that in an eminent degree it has been the embodi- ment of this determined spirit. Whenever men hear this name they have a very clear and definite conception of what it means. Dartmouth has succeeded in creating or man- ifesting a spirit by which it may be known, something that may be said to belong to it. Without neglecting, certainly without despis- ing, the graces and refinements of scholar- ship, it has laid its emphasis upon a certain virility, a masculine vigor of intellect and ef- fort,—what soldiers sometimes call ‘grit and iron’. It is not afraid of difficulties. Rather it asks for something hard to do.

“Dartmouth does not exactly stand for the Montessori system in higher education. It has always harbored a suspicion that one of the principal things to be gained in a place like this is the ability to hold the mind to a dis- agreeable but necessary task. It may find it- self a little old-fashioned herein; but the en- trance list would indicate that there are still a considerable number who share the suspi- cion.”

Judge Stafford illustrated the deter- mined, disciplined seeker and possessor of man’s intellectual inheritance who de- votes his hard-won acquisitions to the public service by the career of Thaddeus Stevens, Dartmouth 1814, who for nine years, and those mostly after the period alloted man by the Psalmist, “stood forth the unequalled champion of free principles,” in the days of the American crisis centering in the Civil War.

“When all deductions have been made, the candid historian of the future' will be compelled to say, that his was the hand, his the indomitable will, his the uncom- promising zeal for the Declaration of Inde- pendence, that, more than any other single man’s, harvested the fruit of those bloody years and made the Declaration and the Con- stitution one. He refused even to be buried in any ground from which the meanest of his fellow men could be excluded; and so he sleeps today in an obscure graveyard in western Pennsylvania, among the children of the despised race which he had given all his dying strength to lift to the fair level of equal and impartial law. I ask you now, if that was not the work of a true Dartmouth man?”

Having interpreted and illustrated the college ideal, Judge Stafford made his application in terms of industrial rela- tions. Propounding the riddle of the Sphinx, he closed as follows:

“The riddle the old Sphinx proposed was this : What creature is it that goes on four feet in the morning, on two at noon, and on three in the evening. The answer was; Man. In the morning he creeps. Ait noon he walks upright on two strong feet. In the evening he limps along with a cane or staff. “Man! Man!” cried Edipus; and the Sphinx was slain. So now, whatever the formula may prove to be, the answer is still, man, the dig- nity, the honesty, the intelligence of man. Our safety can only be found in a policy that treats all men as brothers, all equally entitled to the fruits of their labor, all equal- ly entitled to raise themselves as high as pos- sible, each in his own place, without doing wrong to any of the rest. It is the spirit of justice and fraternity that must be our guide. And where are we to look for leadership if not in institutions as this, especially in this, whose just and democratic spirit is its most distinctive sign, the very hallmark by which it is and always has been known.”

Judge Stafford’s address was not only eloquent, informing and forceful, it was also a beautiful specimen of oratorical art, ■ abounding in apt allusions and quotations, and delivered with the most perfect -mastery.

President Burton followed with an ad- dress on the subject: “What Must the Colleges Do?” Not much in that sub- ject to suggest Eleazar Wheelock and a century and a half history, you say. Well, this was the way of the anniver- sary celebration. The past pervaded the whole event, but the future domi- nated it.

President Burton began by saying that the traditional answers to his theme- question are not sufficient, then, almost paradoxically found his answer in old demands—old, but with new meanings. He argued for accuracy.

“We have been a race of pioneers,” he said. “We have done the best we could. It takes time to develop a sub- stantial civilization. Temperamentally, we are not well equipped for patient, thoroughgoing work.” Now, he main- tained, the time and the conditions of life require delicacy, nicety and preci- sion of thought and action, the vigor of the mathematical and scientific spirit.

Another demand, not new surely, and yet presented in new form, is that the college should produce the “student who studies—-one who is actually concerned about his understanding of truth and life,” and “the teacher who teaches— one who recognizes that a human being is one of the final values of life.” In this connection the speaker said that “every classroom should be permeated with the spirit of cogent discussion, every college should have its forum at which the vital issues of the day are vigorously debated, members of the fac- ulty and students should mingle together and discuss problems on a perfectly nor- mal and human basis. The daily con- versation of students should reflect a natural but genuine concern for public policies. They should anticipate as stu- dents their duties as citizens.”

The following quotation from the end of President Burton’s address provides a key to the whole; “The colleges must be training schools in integrity. This is a strange assertion, but the present world situation justifies it. The war shook the confidence of the world. Mu- tual goodwill and trust are the primary needs of our country today. The falsity of the German educational system has provoked the most careful scrutiny of our colleges and uni- versities. The unescapable lesson of the war is that Germany lacked integrity. She man- ifested it by her duplicity and her repeated efforts to eliminate ethical considerations from international relationships. As the world trusts America, today, so must America be able to trust her colleges.

“The college, therefore, must stand for ab- solute, unqualified devotion to the truth. Hon- est work must be done in every classroom and laboratory. Intellectual integrity must be our first assumption. A general standard must prevail which requires plain honesty and sheer integrity in all collegiate relationships.

“Our colleges must send forth graduates who are not only honest, but who will be ac- cepted by the community as honest. We must keep our hands clean. There must be no smell of smoke on our garments. We must avoid all appearance of evil. In the world the col- lege graduate must be a man who instinctively and incessantly opposes the business man who profiteers, the laboring man who shirks, the politician who sacrifices public weal to pri- vate gain, the citizen who enjoys the blessings of American citizenship, but accepts none of its obligations, the radical who destroys with- out building up, and the conservative who ex- alts the past and neglects the plain duties of the present.

“The future of the college of Liberal Arts is at stake. The situation is critical. Its most glorious days are ahead, if it can train a generation of men who will work accu- rately, if it can awaken its students to the full glories of being alive, if it can help them to know their own day, and above all, if it can make them genuinely trustworthy. These are not new duties. They are the old tasks ac- centuated by the demands of a new day.”

It will be seen that this was an ex- ceedingly practical talk. The word is used with deliberation. It was an ad- dress, big and broad and strong, but the speaker talked as if from a full and overflowing heart, talked as if he and his hearers were a group of college men assembled anywhere, any time, for the serious business of trying to discover “what the colleges must do”.

What Dartmouth purposes to do was told by President Hopkins in the clos- ing address of the Webster Hall exer- cises. Plis address, “a definition of pur- pose” and a Dartmouth “credo,” appears elsewhere in this magazine, but his clos- ing words may be fittingly quoted here in close connection with those of Presi- dent Burton. They were as follows :

“It would be an affectation for us to de- fine the purpose of Dartmouth College in the pious phrases of the eighteenth century, but it would be an unforgivable omission to ig- nore the present day equivalents of the mo- tives which actuated Eleazar Wheelock in his unceasing efforts to establish this foundation. The founder’s altruistic purpose of convert- ing the heathen savage to the glory of God becomes in modern parlance a desire to con- vert society to the welfare of men. Either purpose requires the highest idealism, and the highest idealism is the purest religion, the symbol of which is God and the manifesta- tion of which is the spirit of Christ.

“May this ever be the spirit of Dartmouth College 1”

The exercises closed with the singing of Milton’s paraphrase of Psalm cxxxvi, and the benediction, pronounced by the Rev. William Hamilton Wood, Profes- sor of Biblical Literature, the academic procession reforming and marching out of the hall.

The Pageant and Luncheon

And now a change came swiftly over the whole scene. The Campus was all life and movement. The undergradu- ates, villagers, and visitors from nearby towns gave it a holiday aspect. Caps and gowns disappeared quickly, and those who a moment before had been se- riously considering the future of Dart- mouth mingled with the throng on the Green.

Still, not all the Campus was alive with color and motion, not quite yet, for the walk extending from the White Church diagonally across it was roped off. And here appeared soon certain persons and personages who recalled the past.

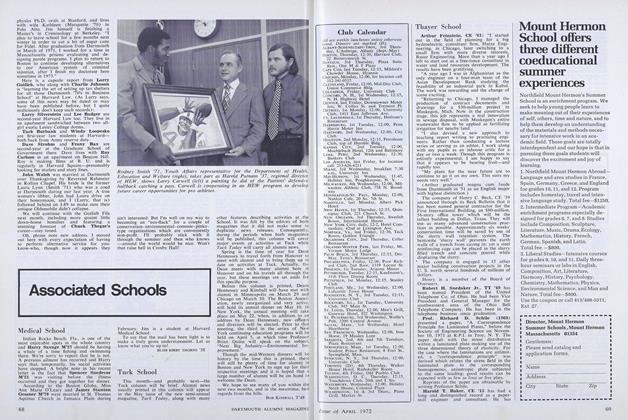

Came the Aborigenes, the objects of Eleazar Wheelock’s deep concern, they whose “ferocity he subdued by the Gos- pel” if memory serves correctly. Then came Wheelock himself, accompanied by Sylvanus Ripley and Dr. John Crane, his companions of the famous ox-cart journey. And Madam Wheelock was there, attended by students and her per- sonal slaves, and manifesting house- wifely regard for the celebrated barrel of New England rum, or, at least, the barrel. Of course, Governor Went- worth came, accompanied by “gentle- men from Portsmouth” as he came long ago, on horseback, from Portsmouth, to attend the exercises of the first com- mencement in 1771. And there was John Ledyard, after his long wanderings, be- ginning with his departure from Han- over in a dugout canoe, and extending around the world. There he was in a sul- ky reminiscent of the one which brought him up from Hartford in 1772.

Almost a half century passed, and then came Daniel Webster and Rufus Choate, sitting together in the chaise that was once Webster’s and now is the property of the College.

It was all neatly done, this pageant of Dartmouth’s past—the impersona- tions being by the members of the Dart- mouth Dramatic Association.

But all has not been told. There was a birthday cake, adorned with candles, telling the story of the progress of the Tucker Foundation and the gifts of the alumni in the last year, listed by classes.

And in the end, there was an episode portraying “Dartmouth, Patriotic Dart- mouth,” in the Revolution, the Civil War and the World War.

All this passed swiftly, and then a dis- tinctly carnival touch was given to the celebration by the appearance of thou- sands of colored balloons. Much as a magician produces a rose bush in bloom from nowhere, apparently, the crowd broke out in floating color. Little cards bearing the greetings of Dartmouth to the outside world were attached to the balloon strings, and up they went, sail- ing slowly away to the north those which didn’t lodge in the trees.

But there was that besides pageantry and balloons which made the Campus an attractive meeting place on Monday. Long tables were spread in the open air and in the tent, which had remained standing, and there the delegates, guests, members of the college community, al- umni, and the student body had luncheon together, a substantial New England luncheon.

This was the period of general jol- lification, a downright good time, out of doors, on one of the most perfect days of the autumn.

At its height, the hum of a motor was heard high in the air and the crowd was gripped by the sight of an airplane cir- cling _ above the Campus. This was a surprise for most. The plane remained in the air a long time, then descended in the field east of the Oval, and was there for an inspection for awhile in the after- noon.

The Educational Conferences

Meanwhile groups of faculty mem- bers, representatives of the colleges, and others assembled for educational con- ferences. One of these had for its gen- eral subject “The Humanities Old and New in College Education.” It took place in the French room in Robin- son Hall, and was conducted by Charles D. Adams. The leaders of the discussion were William Allen Neilson, President of Smith College; Irving Bab- bitt, Professor of French Literature in Harvard University; and Arthur Fair- banks, Director of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Professor Edwin J. Bartlett conducted a conference in Wilder Laboratory on the subject: “The Place of Science in the American College”, the leaders in the discussion being Frank Baldwin Jewett, Chief Engineer of the Western Electric Company of New York City; Alfred Edgar Burton, Professor of Topograph- ical Engineering and Dean of the Fac- ulty, Massachusetts Institute of Tech- nology; and William Francis Magie, Dean of the Faculty of Princeton Uni- versity.

And there was a conference on the so- cial sciences in Bartlett Hall, the subject being: “The Duty of the College in Training for Citizenship.” This was in charge of Professor Herbert D. Foster, and the leaders in the discussion were Felix Frankfurter of Harvard Law School, Kenyon Leech Butterfield, Pres- ident of the Massachusetts Agricultural College; and Alexander Meikeljohn, President of Amherst College.

All were well attended and the papers presented aroused keen discussion.

The Anniversary Dinner

The anniversary celebration ended with a dinner in College Hall, and while the great company began to disperse soon after the Webster Hall exercises, this was not noticeable at the closing event, so large and representative was the gathering.

William Tucker Abbott ’9O, president of the Association of Alumni, presided, and prayer was offered by the Rev. Ben- jamin Franklin Marshall ’97, President of the Connecticut College for Women.

Mr. Abbott mingled pleasantry, rem- iniscence, tradition, and serious reflec- tions of alumni responsibilities in his brief introductory remarks, and intro- duced former President Nichols as the first speaker.

Dr. Nichols began with a tribute to Dr. Tucker in the course of which he said: “It is not only Dartmouth that owes a debt to Dr. Tucker, it is the na- tion and the nation’s thinkers.” And he alluded to the present president, speaking of his courage, his breadth, tolerance, and wisdom. Then he spoke on the theme of college responsibilities, with special reference to the need of educating the public regarding the intent and aims of college education.

Dr. Frederick Carlos Ferry, President of Hamilton College, and a graduate of Williams, was introduced as a represen- tative of this latter “Indianless Indian school.”

In the course of his address he re- viewed a bit of history appropriate to the anniversary occasion, a brief outline of the origin of Hamilton College, which he connected directly with Kleazar Wheelock. Samuel Kirkland studied under Wheelock, went to Princeton, in- terested himself in the Seneca and Onei- da Indians, was ordained at the hands of Wheelock, and went out to preach among the Indians. It was in the days when Wheelock was looking for a site for his proposed college, and the Valley of the Mohawk was considered by him as well as the Valley of the Connecticut. Hamilton College was founded long af- terwards by Kirkland, assisted by Alex- ander Hamilton.

President Ferry talked most entertain- ingly regarding college characteristics. Here is one of his closing sentences: “I opened Dr. Tucker’s interesting book today and read the romance of Dartmouth College as a spiritual ro- mance. And so the spirit of the wilder- ness still lingers about colleges like Dartmouth, Hamilton, Williams, and Amherst, founded back in those days of simple living and of earnest thinking. I congratulate the president and mem- bers of the faculty of Dartmouth Col- lege that they are permitted to follow in the steps of those noble, great men, and that through the tasks they are per- forming here in these days they are es- tablishing their kinship with those great ones of old.”

United States Senator George H. Moses, the next speaker, began his re- marks by reminding the audience what- ever he said was to be “submitted for immediate ratification without amend- ments or reservations.”

The senator gave a typical after-dinner talk for the most part, in the end paying a son’s tribute to his alma mater, and to “that great brotherhood of Dart- mouth men who have gone out to every corner throughout the land, who have steadied and held true the course of events in their communities, and who have contributed so much to the sobri- ety and sanity of American thought and to the steadiness of American advance- ment.”

The toast master propounded a theory that if the Baptists had been as fore- handed as the Presbyterians, and re- formed their practice of making their preachers “peripatetic tramps,” Dr. William H. P. Faunce, President of Brown University, son of a Baptist cler- gyman, and born at Cornish, N. H., would have gone to Dartmouth instead of Brown, but found somewhat of com- fort in the reflection that in this event, President Faunce would not have been at the anniversary celebration in the ca- pacity of guest.

Thus introduced, President Faunce, after a brief word of greeting, in which he said that Dartmouth, geographically remote, is psychologically, socially, polit- ically, educationally, at the very heart of the American continent, went directly to the subject of college duties. He gave one swift backward look to the be- ginnings, saying:

“There were nine of our American colleges founded before the American Revolution—Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Princeton, Pennsylvania, Columbia, Brown, Rutgers, Dartmouth —and every one of them is alive and flourishing today. You cannot kill an American college. It may meet with disaster; it may pass through stormy times. The history of every one of them is a stormy history, but their roots are so very deep in the life of the country that they cannot die. There is not the slightest danger that any one of these colleges founded before the Revolution will disappear while the Republic itself endures.”

The old pioneer work is done, he said. No new colleges are needed in America —at least east of the Mississippi. What then is the work of the existing col- leges ?

“It seems to me,” continued the speak- er, “that our great need today is for pioneers who can blaze the path in that form of social co-operation and world organization which shall give us lasting, enduring peace.”

He proposed college co-operation of a kind and on a scale not attained erto, and college leadership out of “pro- vincialism into some sense of the rela- tions of each one of us to the whole human family.”

“Physical science can bring our bod- ies together,” he said, “but only the col- lege, the church and the social impulse can bring us together in spirit and in heart; and the great task of the college today is, through democracy, to bring the souls of men as closely together as physical science is fast bringing their bodies together.

“What is democracy ? Democracy does not mean a dead level of medioc- rity. Democracy on the hillsides around us does not mean that all the trees shall be alike and of the same height, but that the pine shall be the best pine it can and the oak the largest and best oak it can. Democracy does not mean that one man is as good as another, but that we are to find out who the best are and put them in places of power. It does not mean that one man is as wise as another. Far from it. But it does mean that all men are wise enough to help select the wisest and put them in places of responsibility. That is the sort of democracy for which the American college stands, and for which the nation itself, through it, ulti- mately shall stands.”

Professor Felix Frankfurter, of Har- vard Law School, introduced as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipoten- tiary to everywhere, and then to some- where else, began his vigorous, thought- provoking talk on industrial relations and the responsibilities of the college in this relation by establishing his kinship with Dartmouth, first through his Dart- mouth classmates in Harvard Law School who, he alleged, taught him “that the art of life which is symbolized by the celebrated barrel of rum is not indigen- ous to Hanover hills, but may flourish on the banks of the Charles”—a tem- porarily closed chapter in education, he added; then through Judge Hough, be- fore whom he learned the great lesson “that encouragement is best where most is exacted”; and finally through his as- sociation with President Hopkins in the work of the war. “I take it”, he said, “that I am not the only one who has experienced that subtle, almost unscru- pulous talent, of his, by which he gives you orders by seeming to agree with you”. The address that followed this in- troduction was compact of information, gathered from far and near, regarding the industrial crisis. Social developments in Britain were described briefly but lucidly, and the speaker dwelt at consid- erable length upon the great number of educated men in England who are study- ing social problems with enthusiasm and disinterestedness—more, he said, than in any other country.

With biting irony, he described the “panic” in this country, the seeing of “spooks everywhere, and Red armies”— here where the least has been paid and the least suffered because of the ravages of war; in this country “that should have been the best prepared to meet the new problems and the still unsolved old prob- lems.”

But it is quite impossible to , quote from Professor Frankfurter’s address and do justice to the whole. It was a unit of clear thought, at the center of which was the idea that here, as in Britain, there ought to be a great number of edu- cated and disinterested men thinking on industrial relations, not making “dog- matic assertions in the field of social en- gineering that they would not hazard even on mechanical engineering”, but thinking down into the roots of the soc- ial problem, thinking with “great good will, a great understanding, and the es- sence of all that is tolerance’-’.

The outlook of this closing gathering of the anniversary celebration was to far horizons in all directions—backward to the beginning of American colleges, for out on all sides over the broad fields where pressing social problems await solution, onward to new and larger use- fulness.

The time has come to descend to the plain, and to the daily task. Who is to speak the last word on the mount, and what is that word to be—who but Dean Laycock, and what but a simple, inspira- tional word of gratitude for all the past and faith for all the future?

Here is just a paraghaph from this message to the alumni, the faculty, the college world—it illustrates the whole: “We come here, as it were, at the close of the day. One hundred and fifty years have gone their circle. We stand here, as some of us stood tonight as the sun was setting, and feel that somehow or other a complete day in the life of this college has closed. There is moon- light, music, rejoicing; there is inspira- tion, there is solemn joy. But we must stand as they who wait for the morning, for every college should stand facing the east.”

A few words more, and the celebration had begun to drift into its place in Dart- mouth’s history, leaving Dartmouth “facing the east”.

In closing this narrative of the cele- bration, a word is fitting regarding the arrangements. It may have been that there was at some point a forgotten, neg- lected, or baffling thing. If so, only those of the inner administrative circles could have known of it. To others all that ap- peared was perfect organization, large scale preparation and careful, skilful at- tention to the smallest detail. From be- ginning to end, from the ordering of a great gathering to hospitable attention to the needs or wishes of guests, the cele- bration “went off” as if it were all a part of the day’s work.

CAMPUS SCENES DURING THE CELEBRATION

(Below) The Anniversary Balloons

Patriotic Dartmouth

Governor Wentworth and Gentlemen from Portsmouth

Following the Pageant Luncheon Was Served on the College Green and the Birth- day Cake Was Displayed

A.M., Chief Editorial Writer of the Manchester Union

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE: AN ATTEMPT AT FORMAL INTERPRETATION

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES MEETING

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleNEW ENGLAND STATES

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleThis number of The Magazine

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1919 By Homer E. Keyes -

Article

ArticleTHE CHANGING COLLEGE

December 1919

Article

-

Article

ArticleTucker Foundation Appointments

OCTOBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleON THE JOB

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

APRIL 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS ON ACADEMIC FREEDOM

November 1940 By Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY